Plantation Politics?

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

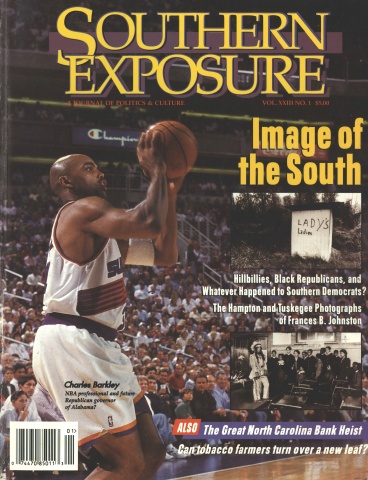

When National Basketball Association star Charles Barkley announced his intention to run for governor of Alabama in 1998, few people paid attention. After all, the Alabama born athlete had made more than his share of outrageous statements during his professional basketball career. But when Barkley announced that he would run as a Republican and that he would ask conservative talk show host Rush Limbaugh and former Vice President Dan Quayle for support, more than a few people took notice.

“People assume that because you’re from the South and you’re black, you must be a Democrat,” Barkley told a crowd of supporters at a conservative function.

Barkley is not alone. Across the South a small but growing number of African Americans, left disenfranchised and alienated by the Democrats, are joining the Republican Party.

“Many blacks have seen the light,” said Armstrong Williams, a South Carolina native and conservative talk show host in Washington, D.C. “We have seen what the Democrats have done, and we still see little progress in our communities. In abandoning the liberal faith, we stand only to lose a ruling philosophy that has brought us nowhere since the 1960s.”

After the recent Republican sweep of the U.S. Congress, Williams wrote in a USA Today editorial, “For too long we have been the silent ignored minority in the black community. No longer. As of this month the conservatives in the black community hold the keys to the kingdom.”

In spite of Williams’ optimism, the vast majority of African Americans remain loyal to the Democratic Party. Most black elected officials are Democrats, and African Americans make up 20 percent of the Democratic National Committee, the decision making body of the party.

While black Republicans in the South and across the nation do not wield that kind of clout, they are growing in size and influence. In 1994, 24 blacks ran on the GOP ticket in the national election. This was up from 15 in the 1992 election. They included J.C. Watts, a former quarterback at Oklahoma University, who became the second black Republican and the only one from a Southern state to be elected to the U.S. Congress in modem times.

In North Carolina two blacks on the GOP ticket were elected to the state legislature. Another black legislator switched parties and became the third black Republican in the North Carolina General Assembly. In Georgia, state Senator Roy Allen, a childhood friend of Clarence Thomas, switched from the Democratic Party to the GOP.

Isaac Washington, publisher of the South Carolina Black Media Group in Columbia, South Carolina, attributes the appeal of the Republican Party to values it shares with the black community. “If you look at the majority of black people, you’ll find them to be quite conservative,” said Washington, who joined the Republican ranks in the late 1970s. “We need a viable two-party system that lends itself to checks and balances. Blacks shouldn’t put all their eggs in one basket. We need to get beyond labels and lever pulling and instead look at issues.”

Party of Lincoln

Being black and Republican may seem strange in today’s political climate, but it was not always so. Following the Civil War, blacks naturally flocked to the ranks of the party of the president who they believed had freed them. In 1868, 703,000 blacks registered to vote, compared to 627,000 whites. From 1870 to 1881, 16 blacks, all Republicans and all from the South, served in the U.S. Congress — two in the Senate and 14 in the House of Representatives. On a local level, blacks in the Republican party served in many prominent positions.

In South Carolina, Robert Brown Elliot, a black Republican was elected state attorney general. Black Republican P.B.S. Pinchback held the Louisiana Governor’s seat for 36 days after the white governor was impeached. Thousands of other black Republicans served in elected positions. Black Republicans also helped to create the first public school system and pushed for land ownership for the recently freed slaves.

Republicans drafted the 13th, 14th, and 15th amendments to the Constitution. These provisions granted African Americans freedom, citizenship, and the right to vote. In 1866 the party also spearheaded passage of the nation’s first civil rights bill.

The election of Rutherford B. Hayes to the presidency in 1877 brought an end to many gains blacks had earned with the Republican Party. Hayes pulled the Union Army out of the South in order to gather Southern support for his presidential campaign. This compromise left blacks at the mercy of the Southern Democrats who were once again in power.

For the next few years both blacks and Republicans were systematically eliminated as participants in Southern politics. African Americans in the North, however, remained loyal to the reform-minded Republicans. This began to change during the great Depression of the 1930s. The Republican party’s refusal to address pressing social needs during the Depression and the popularity of Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt prompted a shift in party loyalty. Blacks ceased to vote Republican in great numbers, except for a brief period during the 1950s when Eisenhower won a majority of the black vote.

Many blacks left the party permanently when Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater ran for President in 1964. In his so called “Southern strategy,” Goldwater urged the Republican Party to forgo the black vote in the South and concentrate on building the white vote.

In 1961 the senator told a group of supporters in Atlanta, “We’re not going to get the Negro vote as a bloc in 1964 and 1968, so we ought to go hunting where the ducks are.” While this “Southern strategy” failed to win Goldwater the presidency, it did succeed in giving the new Republican Party a strong base among white voters in the South.

Black Republicans who have emerged in the past few years bear as little resemblance to their Reconstruction-era forebears as the party itself bears to its own roots in strong centralized government and antislavery sentiments. Today’s black Republicans express deeply conservative values and ideas. They oppose most government aid and social programs. Instead they support:

▲ An end to Affirmative action

According to black conservatives, affirmative action programs lessen the achievements of blacks and lead to resentment among whites who feel that African-American gains are the result of governmental action rather than individual efforts. “We’re not in the business of special treatment for anybody,” said Armstrong Williams. “That’s the message that has to get across.”

▲ An End to Welfare

Like their white counterparts, black conservatives advocate changing or ending welfare programs. They argue that social programs like welfare create a culture of dependency. They approve of proposals to link welfare to job training programs and to end support after two years.

▲ Self-help

Echoing the philosophy of Booker T. Washington (see “From Booker T. Washington to

Clarence Thomas”), conservative blacks support self-sufficiency and entrepreneurship. Their proposals would put government programs into private hands, including private ownership of public housing. They also endorse school choice (the use of vouchers to attend private or public schools).

▲ Family Values and Individual Responsibility

Black conservatives say they want to foster traditional black values, including family, self-reliance, and self-restraint. These values, says Alan Keyes, a black conservative from Maryland who ran for the U.S. Senate and hopes to get the Republican nomination for President, will end the social ills of drug use, teen pregnancy, and fatherless households.

Shift to the Right

Black conservatives contend that African Americans in general are becoming more receptive to their message. They cite a poll by the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies and Home Box Office (HBO) in 1992. Nearly a third of the African Americans surveyed considered themselves conservatives and supported much of the conservative agenda:

♦ 88 percent of the respondents favored school-choice proposals.

♦ 91 percent supported letting tenants buy public housing, a proposal suggested under former Bush Administration Housing and Urban Development Secretary Jack Kemp.

♦ 88 percent supported eviction of tenants from public housing if convicted of selling or using drugs.

♦ 57 percent opposed additional benefits for single welfare mothers who have more children.

Reflecting a trend in the rest of the population, more black men than women voted for conservatives; 22 percent of black men voted for George Bush or Ross Perot in 1992, but only 12 percent of black women voted that way. David Bositis of the Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies, which conducted the study, says use of the poll by conservatives is “highly selective and misleading.” The poll found, for instance, that blacks who considered themselves conservatives endorsed programs many conservatives dislike: 79 percent favored affirmative action; 76 percent wanted to cut defense and use the money for urban programs; 81 percent thought too little money was being spent on education; 83 percent favored Afrocentric education; and 80 percent favored government initiatives to help young black men. Two thirds of all the respondents were Democrats, and 75 percent rated Jesse Jackson favorably.

Given these facts, Rickey Hill, professor of political science at South Carolina State University, doubts that blacks will ever support the Republican party in mass numbers or view black conservatives as leaders. “Black conservatives have no base of support among the masses of black people,” says Hill. “What they do have is access to the airwaves and a presence on editorial pages of some of the leading newspapers. They don’t have a bottom up approach.”

Hill adds that the relatively small black constituency in the Republican Party is not likely to grow. “The last election was billed as a revenge of white males, a population that felt that blacks and other minorities were getting more attention than them,” Hill says. “The Republican party is not going to risk alienating them to attract black voters.”

Data from the Federal Election Commission support Hill’s claims. At the national level blacks make up only three of the Republican National Committee’s 165 voting members. Two of these African Americans come from the U.S. Virgin Islands. In addition, black support for Republican candidates in congressional elections actually dropped from 21 percent in 1990 to 12 percent in 1994.

In the South, where the majority of the nation’s blacks live, Republicans have made few inroads into the African-American community. This is due in large part, says Bositis, to recent history.

Destructive tactics by Republicans included race-baiting in the 1990 United States Senate campaign of black candidate Harvey Gantt who ran against Senator Jesse Helms in North Carolina. The creation by the late Lee Atwater of the Willie Horton ads in the 1988 Bush campaign set up an ugly, unwelcoming atmosphere for blacks in the Republican party. Recent campaigns used references to black women as welfare mothers and covert references to race and crime designed to appeal to Reagan Democrats and play on white fear of black criminals.

“The present leadership in the GOP, the Congress, and the Republican National Committee is increasingly Southern in make up,” says Bositis, “The Southern conservative wing of the GOP is most insensitive to the feelings of the African-American community and generally offers nothing to attract black support.”

This, says Hill, means blacks can expect little from the Republican Party or their conservative allies in the black community. “What we need to be concentrating on is independent politics,” says Hill, “Nothing can be gained by repeating the Republican party line.”

Armstrong Williams disagrees. “We need to take advantage of having a choice by giving the GOP a look,” Williams wrote in a State newspaper editorial. “They have begun to reach out, but it takes two hands to shake.”

The Race Racket

Critics charge that black conservatives, in sharp contrast to their public stance on black empowerment and self-sufficiency, have opposed programs that would empower the black community. “These people are nothing more than political mercenaries,” says Bob Holmes, Director of the Southern Center for Studies in Public Policy at Clark Atlanta University. “They are trying to help reimplement policies that have been shown to be detrimental to the black community.”

One example, says Holmes, is the battle over black congressional districts in the South. Created as a result of the Voting Rights Act, black districts have given African Americans the largest number of representatives since the Reconstruction era, ensuring that blacks have a voice in the electoral process. A court challenge to the district was initially filed by a white Democrat.

But many black conservatives have also attacked the districts as racial gerrymandering. In Georgia a panel of three judges struck down Representative Cynthia McKinney’s newly created 11th district as unconstitutional based on a dissenting opinion in another voting rights case by Supreme Court Justice Clarence Thomas.

In the opinion, Thomas called for a complete reinterpretation of the 1965 Voting Rights Act. He wrote, “This court is not a centralized politburo appointed for life to dictate to the provinces the ‘correct’ theories of democratic representation, the ‘best’ electoral systems for securing truly ‘representative government,’ the ‘fairest’ proportions of minority political influence.”

Gary Frank of Connecticut, the lone Republican member of the Congressional Black Caucus prior to the 1994 election, joined several whites to testify against the district, saying that it was a form of racial gerrymandering that would only divide voters along racial lines. Brenda Reddix Smalls, a civil rights attorney in Columbia, South Carolina, says the black conservative rationale for speaking out against black districts is flawed. “Those who would argue against single member districts or redistricting, anything that gives blacks a chance to have some form of power in the political process, are lacking in one historic truth,” she says. “You can’t deal with people in power without having power. . . . The idea that if we all somehow become mainstream, just all be Americans — not black or white, then we wouldn’t need these districts — simply doesn’t hold up.”

Not all the attacks have come through the political arena. Some black conservatives, critics say, have used their political and business ties to derail other forms of black advancement. One target of frequent criticism is James Meredith, a veteran of the civil rights movement and the first black to attend the University of Mississippi. In 1990 Meredith threatened to expose civil rights leaders, saying they were being controlled by 15 powerful white men of the liberal elite and engaged in illegal and immoral acts.

Meredith surprised those who knew him from his civil rights days by going to work for North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms as a congressional aide, despite the fact that Helms had opposed programs aimed at helping blacks, supported the apartheid government of South Africa, and opposed creation of a Martin Luther King Jr. holiday.

Responding to the charge of Helms’ hostility to blacks in a 1990 interview, Meredith told the New York Times, “I have never seen anyone sustain that charge or give one iota of evidence. The truth of the matter is that the liberal elite with knowledge and full thought on the part of the black elite have deliberately set up a phenomenon as part of their political power control of taking a handful of selected blacks, giving them power and using them to control the black population.”

Meredith also supported the presidential candidacy of Louisiana Klansman David Duke in the 1992 election. Meredith himself ran an unsuccessful campaign in 1992 for the Mississippi congressional seat vacated by former Agriculture Secretary Mike Espy.

Another black conservative who has come under increasing scrutiny is Robert Brown, founder and President of B&C Associates in High Point, North Carolina. Brown, described in his press biography as a grandson of slaves and a self-made millionaire, served under former president Richard Nixon as a White House Advisor on Minority Affairs. Brown was also a friend of deceased civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. Brown bills his organization as a public relations and management consulting firm, but opponents say it serves another purpose.

“At national civil rights conferences, B&C presents itself as one of the oldest and most respected black-owned public relations firms in the nation,” says Clayola Brown, Director of the Civil Rights Department of the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union (ACTWU). “But in communities where African-American workers are struggling for basic rights on the job by trying to organize a union, B&C operates as union busters disguised as civil rights consultants.”

According to a report by the ACTWU, “Ball and Chain for African-American Workers,” Brown and B&C are regularly employed by corporations to keep out unions among their African-American workers. The report also says that Brown and B&C have used well known celebrities such as Oprah Winfrey’s fiancé Stedman Graham and former Sanford and Son star Whitman Mayo (who played Grady) to help improve the image of B&C clients in black communities before union elections. Graham works for a subsidiary of B&C, the Graham Williams Group. Armstrong Williams, who worked for Brown as vice president for governmental and international affairs, is president of the Graham Williams Group.

Allegations against B&C associates first surfaced during the early 1980s. The charges helped derail President Reagan’s nomination of Brown as ambassador to South Africa. Even though Brown had the support of civil rights leaders Coretta Scott King and Andrew Young, his nomination was withdrawn after the alleged activities of his firm became public. Labor leaders charged Brown and his company with working for Fortune 500 corporations such as Cannon Mills and Sara Lee to discourage African-American workers from unionizing.

A former employee of B&C, Rosalyn Shelton, says she helped to organize anti-union front groups and workers and to arrange payoffs to area ministers to defeat a union drive at the Tultex Corporation in Martinsville, Virginia.

John Langford, a black attorney in High Point, North Carolina, charges Brown with using his background and ties to the civil rights movement to make money for himself and to obtain right-wing money for civil rights causes. According to Langford, Brown gives money that B&C gets from its union-busting activities to civil rights’ organizations to garner their support.

Officials at B&C deny anti-union work or any ties to right-wing causes. But Brown did hold a $100,000 fundraiser for North Carolina Senator Jesse Helms. Brown also raised money for Jesse Jackson. “He’s such a good fundraiser that people like Jackson stay close to him despite the connections to people like Helms,” says Desma Holcumb, research director of the ACTWU. “Brown can bring in big money from corporate sponsors.”

B&C and its employer, Lee Apparel, recently settled a complaint with the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) filed by the Teamsters Union. The union and the NLRB charged B&C with spying on workers at the Lee plant. As part of the settlement, the company must post a sign stating that Lee, B&C, and a consultant hired by B&C would not interfere with workers’ right to unionize, would not interrogate workers, and would not discourage them from organizing.

Neither B&C nor Brown would return calls for an interview. Lee Apparel, however, denied any wrongdoing. “There is no admission that we have done any of these things,” says Don S. Hancock, Lee’s area human resources manager, referring to the settlement. Hancock says the company hired B&C for advice on management, union issues, pay, and other issues. He denies that the firm was hired to defeat the union.

Desma Holcomb is skeptical. “If they hadn’t done anything wrong, they wouldn’t have reached a settlement,” she says.

One black conservative who is unabashed in her connection to the white right is Phyllis Berry Myers, of Baltimore, Maryland. Myers is the producer of A Second Look, a television program aimed at black conservatives. Broadcast in more than 30 states, the show is developing a grassroots activist network within the black community in response to the traditional black leadership, according to Myers.

One of her targets is the NAACP. In an interview in Emerge magazine, Myers says the civil rights organization is “advancing an agenda that is anathema to black America.” She urges blacks to fight the NAACP by withholding dues and boycotting sponsors.

Myers worked with white right-wing extremist Clint Bolick of the conservative Institute of Justice to sink the nomination of Lani Guinier to head the Justice Department Civil Rights Division. They produced a number of articles, op-ed pieces, press releases, and reports which portrayed Guinier as a fanatical left-wing “quota queen” bent on undermining democratic principals.

Myers’ program is broadcast by the Free Congress Foundation, a right-wing think tank founded by Paul Weyrich. Weyrich is credited with rebuilding the right into a modem political force. He has built a national infrastructure of think tanks, special interest organizations, programs like A Second Look and a similar program aimed at Hispanics, publications, and a computerized fundraising network.

“Groups like this pose a clear and present danger to the hope of any progress of civil rights in this country,” says Charles Ogletree, a professor of law at Harvard University. “They don’t have a proactive, forward-looking agenda for African Americans. They don’t deserve our blessing or attention.”

Isaac Washington warns that all black conservatives should not be judged by the actions of a few. “Black liberals and Democrats have people who work against the interest of black people, too,” Washington says. “There are problems in both parties. You can’t just point the finger and judge black Republicans.”

David Harris, an attorney with the Land Loss Prevention Project in Durham, North Carolina, agrees. “But we have to remember that many of the rights that we enjoy today came about because of people like the NAACP who may be considered liberal. Many conservatives, on the other hand, have gotten into a position where they want to close the door on other African Americans to keep them from advancing.”

“The importance of these ties is not white conservative patronage per se,” writes Deborah Toler, a research affiliate with Political Research Associates. “Black liberals benefit from similar ties to liberal institutions. A critical intellectual difference is that black liberal analyses and policy ideas originate in their experience in the civil rights and black power movements . . . and continue to be shaped by their black constituents who fund civil rights organizations and elect them to office.

“It is important to question the implications of the fact that black conservatives’ arguments originate in white conservative arguments, and that black conservatives are in no way answerable to a black constituency.”

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.