This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

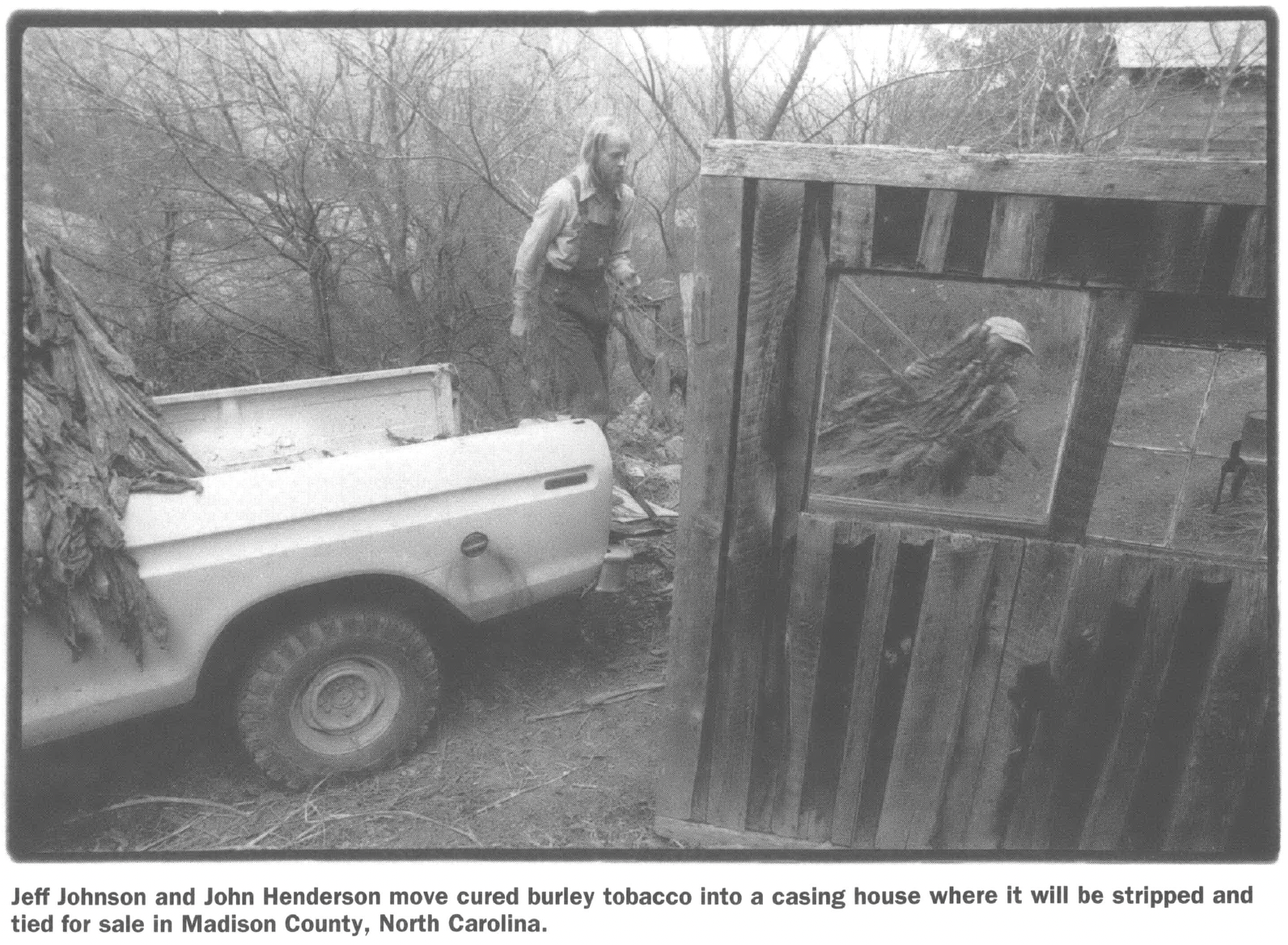

Buddy Switzer smokes a cigarette as he walks through his tobacco barn in Cynthiana, Kentucky. Dried burley leaves hang high in the rafters, absorbing moisture from the late-autumn air. The local tobacco auction starts the next morning, and several men have spent the day stripping supple, reddish-brown leaves from their stalks and separating them by color and texture.

It is an old ritual. Here among the rolling fields along the South Fork, just north of the sprawling horse farms and suburban subdivisions of Lexington, Switzer and his ancestors have been growing air-cured tobacco for well over a century. “My father raised tobacco, and so did my grandfather and great-grandfather,” he says. “It’s something I’ve done and my family’s done all our lives. It just grows on you.”

Tobacco is the mainstay of the farm, but it’s not all that brings Switzer out to the barn these days. Much of the dirt floor is piled high with hardwood maple logs that he hauls down from Ohio, splits into foot lengths, and sells to homeowners for heating and to restaurants for cooking. Year before last he delivered nearly 170 loads and made $17,000.

Outside the barn, only a few scattered stalks of tobacco betray its importance as a crop. Indeed, the fields look more like a demonstration farm than the center of the nation’s biggest burley tobacco region. Thirty-six beef cattle and their calves roam a nearby hillside, next to the skeleton of a greenhouse where hydroponic tomatoes grow. Down in the bottom, fields kept chemical-free for three years produce organic vegetables for a local grocer and alfalfa hay for thoroughbred farms. This year, only four of the farm’s 80 acres were devoted to tobacco.

“We’re growing less tobacco than we’ve ever grown,” says Kim Switzer, Buddy’s wife. “The idea was to give us more time to put up the greenhouse and expand our alfalfa and buy extra cattle.”

The Switzers are diversifying for a very simple reason: All across the South, tobacco production has been declining steadily over the past decade. Last year tobacco farmers planted 200,000 fewer acres and harvested 14 percent less than they did in 1984. Fewer smokers and higher cigarette taxes have contributed to the downturn, but the real culprit is corporate flight. American tobacco companies now buy and produce much of their product in cheaper African, Asian, and Latin American markets, cutting the U.S. share of the world tobacco supply by nearly two-thirds since 1959.

As increasing imports tarnish the “golden leaf,” thousands of farmers like the Switzers are looking for alternatives to what has long been the most stable and profitable crop in the region. Some are turning to conventional crops like vegetables or strawberries. Others are trying to create new markets by selling directly to consumers at farmer’s markets or buying clubs. A few are rediscovering old ways of farming like organic growing and other forms of sustainable agriculture.

Farmers are also organizing. In Kentucky, the Community Farm Alliance has proposed reinvesting any new excise taxes on tobacco in rural communities to help farmers make the transition to other crops. Just as the end of the Cold War created a “peace dividend” by rendering many military industries obsolete, farm advocates say, the public health battle over smoking offers a rare chance to support tobacco farmers who convert to non-lethal crops.

Far more is at stake than the 115,000 farmers who still grow tobacco. Federal price supports for the crop have preserved small family farms in an era of huge agribusiness, and many rural communities depend on tobacco for as much as half of all personal income. Without federal support to develop other high-value crops and markets, more Southerners will be driven into poverty, and more farmland will either fall into the hands of large corporate growers or disappear entirely.

“One of five dollars here in Harrison County is tobacco related,” says Buddy Switzer. “Those are big numbers. You start dropping out tobacco, your banks take a licking, your car dealerships take a licking, your downtown businesses, your Wal-Mart takes a licking. I’m 40 years old and I can count on my fingers the guys I grew up with who are still farming. I graduated with 200 people and probably five of them are farmers.”

“A lot of people in this area are going to be hurt hard,” adds Kim. “We may be able to survive, but what’s the point of staying in Cynthiana if there’s not going to be a community?”

From Exporter to Importer

Tobacco was an integral part of the economy and culture of America well before the nation was founded. John Rolfe, the Jamestown settler who married Pocahontas, grew the first crop shipped to England in 1613. Within four years, tobacco exports totaled 10 tons. Bundles of leaves were used as colonial currency and served as collateral for loans from France that financed the American Revolution. By the time Thomas Jefferson had tobacco leaves engraved on pillars inside the Capitol, the new nation was exporting 100,000 tons of tobacco annually.

Like oil, coal, and railroads, tobacco was lucrative enough to attract its share of robber barons. Even after the Supreme Court busted the “tobacco trust” in 1912, a handful of cigarette companies continued using large stockpiles and secret grades to shortchange farmers. Growers organized a voluntary association and unleashed night riders on uncooperative farmers, but the violence proved no match for the financial power of the buyers. Tobacco manufacturers “have as complete a monopoly as this nation has ever seen,” Governor Richard Russell of Georgia observed in 1932.

To level the field, farmers turned to the New Deal. In 1938 Congress passed the Agriculture Adjustment Act restricting the domestic supply of tobacco. Farmers who were growing tobacco at the time were granted a quota — in effect, a federal license to raise the crop. Tobacco farming became an exclusive club, with new members admitted only if they bought or leased a quota from a Depression-era farm. Lower tobacco supplies meant higher prices, and higher prices meant no need to support farmers with direct government subsidies.

But the U.S. Department of Agriculture continues to support a complex infrastructure designed to keep the crop profitable. Each year the USDA determines how much tobacco should be grown based on how much tobacco companies say they will buy, and then tells quota holders how many pounds they can raise. The USDA also adjusts the “support price” for the crop, guaranteeing farmers enough income to cover rising farm costs. If any leaf fails to bring the minimum price at auction, the government lends money to a “stabilization cooperative” to buy, process, and store the unsold leaf. The co-op later sells the surplus tobacco, using the money to repay the government loans and assessing farmers and cigarette makers to cover any losses.

In addition to protecting prices by limiting supply and providing low-cost loans, the government also grades the leaf, collects and analyzes market information, and provides funds for research and education. It’s centralized planning on a remarkable scale, and it guarantees tobacco farmers prices well above what they receive for other crops. And because smokers pick up most of the tab through higher prices, the entire system costs taxpayers little or nothing. The Congressional Research Service puts the annual price tag for administering price supports at $16 million. By contrast, tobacco farmers paid $22 million in special assessments last year to help reduce the deficit.

“It’s always been a social program,” says Hal Hamilton of the Community Farm Alliance in Berea, Kentucky. “It’s never been a program to create an effective system of growing tobacco. It’s a federal intervention to disperse the benefits of the tobacco industry among a lot of people.”

By dispersing an annual crop worth $2.9 billion, tobacco has given small Southern farmers a way to survive. Kentucky and North Carolina produce 65 percent of all domestic leaf, while another 26 percent comes from Tennessee, Virginia, South Carolina, and Georgia. According to the latest Census of Agriculture, three fourths of all tobacco-producing farms have fewer than 180 acres in a nation where the average farm covers 462 acres. “If it weren’t for tobacco, we wouldn’t have small farms,” says Dick Austin, a farm activist who leases out the tobacco quota on his small mountain farm in Dungannon, Virginia.

Over the years, however, farmers have been hit with a double whammy: smoking tapered off as evidence emerged of its adverse health effects, and tobacco companies and the World Bank helped Third World growers raise leaf at about half the domestic price. Beginning in the early 1980s, the six leading cigarette makers simply stopped buying as much American tobacco as they had promised, creating a domestic surplus of 800 million pounds. In 1985 the companies bought the stockpile — but only after forcing farmers to lower prices and cut domestic production by 10 percent annually.

“The handwriting is on the wall,” the Rural Advancement Fund, a North Carolina-based advocacy group, reported at the time. “The federal tobacco program is on the verge of collapse, and the small tobacco farmer is going down first.” The group called for a “Commodity Transition Program” to help tobacco farmers switch to other crops. “Our goal should not be to save tobacco, but to save those whose livelihoods depend on tobacco.”

The handwriting may have been on the wall a decade ago, but it went unread by the public institutions charged with assisting farmers. Tobacco growers diversifying in the early 1980s received little support from either county extension agents or land grant universities. “Extension was way behind and the universities have been in a kind of dark age. They can’t teach what they don’t know,” says Betty Bailey of RAF-International, who is working to shift the focus of public research with rural development funds.

Many researchers agree. “Organic and other alternatives have been a blank screen for us,” says Mike Linker of North Carolina State University. “You can’t give farmers any info if you ain’t done the research. It hasn’t been a high priority for anyone up until now. The money just hasn’t been there.”

Even when the money is there, however, many growers continue to spurn alternatives and support the same cigarette companies that are forcing them to cut back the amount of tobacco they grow. In August, 3,000 tobacco farmers provided the industry with a much-needed grassroots lobby when they marched on Washington to protest a proposed 75-cent-a-pack increase in the cigarette tax — even though $100 million of the money was earmarked to help farmers make the transition to other crops.

“The fight is really about manufacturers’ profits, and farmers are pawns,” John Bloom of the American Cancer Society’s Tobacco Tax Policy Project said at the time. “At the political level, the manufacturers seem to be the ones calling the shots.”

The manufacturers also strike back when growers show signs of independence. In 1992, for example, farmers backed a domestic content law limiting cigarettes sold in America to no more than 25 percent foreign tobacco. The companies responded by cutting their domestic purchases even more. By last year another 700 million pounds of tobacco had piled up, fueling fears that the USDA would slash domestic production by 40 percent to create demand for the surplus. Tobacco-state representatives forced industry officials to the bargaining table, and in December five companies agreed to buy the latest surplus — at a discount of $66 million.

As a result, the USDA actually raised this year’s quota by 16 percent. But few think the one-year production hike signals a long-term turnaround. James Graham, North Carolina Agriculture Commissioner, calls the boost “a reprieve for a dying man.” In effect, the issue is not whether tobacco will be grown, but rather who will grow it, and who will profit. Last year Brazil surpassed the U.S. as the leading exporter of all tobacco, and Malawi took the top spot as chief burley exporter. And the flow of cheap imported tobacco is likely to increase, thanks to the recently approved General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade. An international panel recently ruled that the United States domestic content law violates GATT, a decision which threatens to undermine the only real protection for American farmers.

Even the staunchest allies of growers seem to have abandoned hopes of salvaging the current system of price guarantees. Last October, North Carolina Representative Charlie Rose, one of the most effective advocates of tobacco farmers, proposed eliminating price supports entirely by “buying back” quotas from growers. Although the plan would provide some capital to quota holders to help them make the switch to other crops, it would do nothing for tobacco farmers who rent quotas from others. What’s more, the plan would return tobacco to the inequities of the free market, eventually shifting control of tobacco production to large corporate farms that could grow the leaf more cheaply.

Making the Switch

Despite the economic and political decline of tobacco, the Southern states most dependent on the crop have done little to develop viable alternatives. Kentucky and North Carolina have encouraged tobacco growers to contract with large corporations to raise chickens and hogs — deals which generally saddle farmers with huge debts and rob them of control over production. Others have put their hopes in genetic engineers who are injecting human genes into tobacco plants to create a new source of protein, and developing a “drug-free” strain of hemp — a.k.a. marijuana — to be used in paper and fabric production.

Many growers also remain reluctant to kick the tobacco habit. Addicted to high prices and a guaranteed market, farmers generally downplay the deadly consequences of the crop they raise. Last year tobacco killed 434,000 Americans — more than twice the combined death tolls from alcohol, car accidents, AIDS, suicide, homicide, fires, and all illegal drugs. Last year in Kentucky, the Farm Bureau erected billboards of four defiant farmers beneath the slogan, “We’d Rather Fight Than Quit.”

“Where things really differ is between old farmers and young farmers,” says Dick Austin, the Virginia farm activist. “The old farmers just want to hang on until they retire; they don’t want to think about change. The younger farmers are already moving out of tobacco. The problem is, there are a lot more older farmers than younger farmers.”

Some younger farmers made the switch years ago. Ken Dawson helped raise tobacco on his grandfather’s farm as a boy in Pittsylvania County, Virginia. But after studying chemistry and religion at the University of North Carolina, he moved in with a friend, consulted a book, and planted an organic garden in 1973.

“I thought, ‘Granddad would think this was a hoot, planting with a book.’ But with beginner’s luck and a lot of well-rotted manure, we were on our way,” Dawson says.

Four years ago, on his 40th birthday, Dawson bought a tobacco farm just north of Hillsborough, North Carolina, and began converting it to organic produce. “I wanted to do something to have some small impact of redirecting the course agriculture is taking in this country. I realized the only thing I could do is develop an agricultural operation that showed how things could be done and do it well enough that people could see it was viable.”

Dawson revitalized the tobacco-depleted soil by planting clover and a viny plant called vetch to add nitrogen. Soon he was selling 25 different organic vegetables, herbs, and cut flowers at a local farmer’s market and grocery store. Most conventional crops cannot match the per-acre return of tobacco. But because organic produce is in demand and Dawson sells much of it directly to consumers, he can actually command higher prices. This year he expects to net more than $25,000 on three acres — well above the average net of $7,500 for an equivalent amount of tobacco.

“The small scale means I can use each piece of ground for what it will do best,” Dawson says as he examines some lettuce planted on a patch of dry, sandy soil. “And the diversity of crops means I never have all my eggs in one basket. If my lettuce doesn’t do well, I always have broccoli and basil and flowers.”

Such diversity is essential for growers making the switch from tobacco. The problem is simple economics: If thousands of tobacco farmers suddenly switch to vegetables, they will flood the market and drive down prices. “The real key for growers as they move to something new is they’ve got to be diversified,” says Mike Linker of North Carolina State University, who uses Ken Dawson’s farm as a research lab. “If they think they’re going to be the squash king or the broccoli king, they’re going to be in big trouble.”

Broccoli and Beef

Charlie O’Dell, an extension horticulturist and associate professor at Virginia Tech, had dreams of being the broccoli king of Virginia. “In 1982, a group of tobacco farmers actually came to the university and asked for help. They had lost almost half of their tobacco acreage due to declining markets. We came up with broccoli as having a real niche at that time.”

More than 100 tobacco farmers began growing a few acres of broccoli, hoping to pool their crop to compete with California suppliers. “It was profitable for a few years, but growers could not get supply and demand in balance,” O’Dell laments. “Now it’s a cut-throat situation — they’re just trying to kill each other off.” Unable to suffer any more losses, organizers closed the market and tobacco farmers gave up on vegetables.

“The answers I thought we had have turned pretty much into disasters,” O’Dell confesses. “I even have a broccoli-green car. Now I don’t know what crop to turn to. Maybe I should paint the car red for tomatoes or strawberries. I don’t know what to do.”

Such confusion arises from asking the wrong questions, says Cornelia Flora, director of the North Central Regional Center for Rural Development at Iowa State University. “Seeing the problem in terms of replacing tobacco with another crop means we haven’t been looking at the right problem,” she says. “We’ve seen this all over the South. What happens is, the first year everybody grows tomatoes and makes a lot of money. The second year the price just goes down the toilet. There’s no planning and paying attention to the market, so it doesn’t work.”

Tobacco brings a high price, Flora adds, “because planning eliminates the market risk. What made tobacco the wonderful crop it was for small farmers throughout the South is that tobacco farmers were organized in a small market association that allowed them to limit supply. Farmers ask, ‘What other crop will I grow?’ They need to ask, ‘How can I get the same advantages I did with tobacco with whatever other crop I grow?’”

Laura Freeman began asking that question in 1984. Although her family has grown tobacco in the Appalachian foothills around Schollsville, Kentucky, since the Revolutionary War, she decided to raise cattle instead. “The farm my mother inherited used to have its own tobacco warehouse and everything,” she says. “But when my husband and I came, we could see tobacco was a dying business.”

Then came the drought of 1983, and a federal dairy buyout the following year. “I learned I had no control over the end price of the cattle,” Freeman recalls. “It was devastating financially. So I said we’ve got to get control of our lives here. We have to get control of the end pricing.”

Freeman tried to get local farmers to start a cooperative to raise organic beef and sell directly to customers at retail prices. But the marketing and packing problems proved overwhelming, and farmers were unwilling to shoulder the risk. So Freeman mortgaged her farm and started her own business buying low-fat beef from 100 farmers and selling it to grocery stores. Last year Laura’s Lean Beef sold 10,000 head of cattle to 1,000 stores and posted retail sales of $15 million.

“We produce a more valuable critter — one with more meat — and we cut our input costs by eliminating drugs and fertilizers,” Freeman says. “We go in and negotiate a pre-determined price for the cattle and pay a significant bonus to the farmers.”

Freeman cautions, however, that her example offers no easy solutions for tobacco farmers. “It’s very difficult to make one of these things successful. They have to make good business sense. It’s a whole ’nother occupation. I don’t farm anymore. I go to an office, I deal with buyers, I deal with ad agencies. I’ve seen 50 or 60 farmers go belly-up trying to make one of these things work. If you’ve been producing on a subsidy program like tobacco where you’ve got a government-guaranteed fixed price, it’s sort of like being an Eastern European farmer. You’ve got to learn how to function in a marketplace whether you want to or not.”

Homegrown Alternative

Across town from Freeman’s office in Lexington, a fledgling group of 27 farmers has started a pilot cooperative to sell organic vegetables directly to restaurants and consumers. The Kentucky Organic Growers Association tries to provide a stable market by having farmers sign commitment sheets saying how much of each commodity they will raise. “We learned a lesson from how the burley growers control their supply,” says Pam Clay, director of the project. “We tried to guess how much produce we would need based on how many farmers and how many buyers we had.”

They guessed wrong. “We were way off,” Clay laughs. “We thought we could sell $125,000 worth of produce, but it was more like $60,000. Reality hit us pretty quickly.”

Still, the co-op has had an impact in its first year. By the end of the season, more than 100 shoppers had paid $500 to join a buying club entitling them to a bag of fresh organic produce each week. Anti-smoking groups like the American Cancer Society pitched in to help sign up consumers, and tobacco farmers began to realize that alternatives like organic vegetables could be profitable. The co-op receives free office space in the headquarters of the Burley Tobacco Growers Cooperative Association, long a vocal opponent of alternatives.

“In Kentucky, organic growers have been stereotyped as old hippies who aren’t really farmers and don’t know how to make any money,” says Clay. “Now no one is laughing at us. We changed the way people look at organic producers.”

Martin Richards describes the change as he walks through the hilly fields of a tobacco farm he converted to organic production near Versailles, Kentucky. “You take a tobacco farm and start growing flowers and your neighbors look at you kind of funny. But it’s a sign of the times that more farmers are willing to consider anything that works. Money talks.”

Richards and Clay know that many tobacco growers will never make the switch to organic, and hope the cooperative can expand into beef, poultry, and conventional crops. Perhaps more important, they hope it can help farmers forge direct links to consumers. “People who buy from us feel more connected to farming,” says Clay. “They meet farmers and hear about what they’re going through. And they don’t mind spending more money if they’re investing in their local communities.”

Investing in local tobacco communities is at the heart of the proposal by the Community Farm Alliance, the Kentucky group which launched the organic co-op. Collaborating with farmers and legislators from across the political spectrum, the Alliance drafted a plan for a Tobacco Regions Reinvestment Fund. The fund would receive a portion of any new federal excise tax on tobacco to provide loans and technical assistance to retool tobacco farms and warehouses, conduct market studies, and research and evaluate alternative enterprises.

“Just as there is no silver bullet to cure the nation’s economic problems, there is no one answer for tobacco growers who face a declining demand for their product,” the plan concludes. “There is no single, high-value crop to replace tobacco, nor a single market channel to be created or subsidized. Instead the answer lies in a more complex, yet ultimately more long-lasting, solution: the development of agricultural infrastructure so that farmers can grow, sell, and process a wide variety of commodities other than tobacco.”

In short, the government would do for other crops what it has done for tobacco — provide low-cost loans, conduct marketing studies, support education and research, and oversee a system to receive, process, package, and market alternative farm products. “Capital availability is one of the obstacles to successful diversification,” says Hal Hamilton of the Alliance. “We figure if there is going to be a big tax, some of it should come back to the regions that are going to be hardest hit.”

The alternative, Hamilton says, is to let corporate giants have their way. “Leaving it all to the free market means leaving it all up to Campbells and Tysons — and therefore consigning farmers to be producers of low-value, bulk commodities. I guess we’re trying to create an enclave for small-scale, progressive capitalism in Kentucky. Socialism in one country never really worked; I don’t know if progressive capitalism in one state will fare any better.”

Whether or not the Alliance plan is adopted, most observers agree that unless the government starts helping small family farmers make the transition from tobacco to other crops, few will be able to fend for themselves. “The worst thing that can happen is for farmers to be expected to solve it one farm at a time,” says Betty Bailey of the Rural Advancement Fund International. “Outside of tobacco and peanuts, huge multinational corporations control almost all of our food and fiber. All we want is for government to be a referee and make people play by the rules.”

Farm activists concede that the Republican victory in the November elections probably killed any chance for a new tobacco tax that could fund alternatives. Representative Thomas Bliley of Virginia, who takes over as chair of the Health and Environment Subcommittee, vows he will end the congressional investigation of the tobacco industry because “I don’t think we need any more legislation regulating tobacco.” Bliley, a pipe smoker who hails from a district where Philip Morris USA is the largest private employer, received $93,790 from tobacco-related interests from 1987 to 1992.

Dick Austin, the Virginia farmer who helped launch the Community Farm Alliance proposal, says that the political shift in Washington simply gives farmers in the South more time to create viable alternatives. “If our dreams had been realized and we got tax money from a health care bill this year, a lot of it would have been wasted on harebrained schemes. So it may be just as well to get some real pilot projects up and running to see how these things actually work.”

Austin and his neighbors have launched projects to help tobacco farmers sell vegetables to restaurants and harvest wood for craftspeople and furniture makers. They are also developing a real estate database to help beginning growers acquire farmland that might otherwise be grabbed by land speculators or timber companies.

“All of this could obviously be done a lot faster with big hunks of federal tobacco money coming back into the community, but in the meantime there’s no excuse not to get started,” Austin says. “The world goes on despite Republicans. Sooner or later there will be a tobacco tax because it’s the only new tax the American people will tolerate. If we’re ready, we ought to be able to use some piece of it to help the people of our region.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.