This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

Several years ago, poultry surpassed beef as the meet of choice for Americans, and its popularity just keeps growing. According to recent Census Bureau data, poultry and poultry products sales were $15.4 billion in 1992, up from $2.7 billion in 1987. And according to a recent Wall Street Journal, the poultry industry has emerged as one of the fastest growing occupations in the country.

In 1989 Southern Exposure investigated the rise of the poultry industry and the rough working conditions endured by its workers. At that time the magazine reported on how the Center for Women’s Economic Alternatives was helping women in the plants fight for better conditions and for compensation from injuries.

Today, workers need help more than ever. Poultry workers, most of whom are poor black and Hispanic women in the rural South, are expected to process chickens faster than ever, causing more repetitive motion injuries. Other working conditions continue to be difficult. At plants such as Perdue and Tyson, employees work on a high-speed line processing 91 chickens per minute. They stand eight to 10 hours a day in water, chicken fat, and ice.

The most common problems workers develop are repetitive motion illnesses, injuries to the wrists, hands, and back caused by the high speeds of the processing lines. According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, 693.4 per 10,000 workers in the poultry slaughtering and processing industry suffer from repetitive-stress injuries like carpal tunnel syndrome. Only the meat packing and auto industries have higher rates of injury.

To add insult to injury, nurses and doctors paid by the plants often misdiagnose or fail to tell workers the seriousness of their illnesses. Furthermore, workers say they are fired if they are unable to perform and are not compensated for doctor visits or medical bills. “They treat us like dogs or worn out shoes,” says Shirley Tripp, a former Perdue worker.

In addition to the physical mistreatment, many women at the plants say they are harassed by supervisors and shift foremen for sexual favors in exchange for less work or time off. If they refuse, they are given additional work or subjected to further harassment.

The Center for Women’s Economic Alternatives in Ahoskie, North Carolina, continues to serve as a resource to workers mistreated and discarded by the poultry industry. Founded in 1984 to combat mistreatment of women in a hosiery mill in Scotland Neck, North Carolina, the center’s major thrust is now the poultry industry. Its staff of four educates, organizes, and supports low-income women’s efforts to identify and develop leadership among workers in order to change inhumane working conditions.

The mission of the center is to create a workplace environment free of oppression where women can earn a decent wage without being exploited. Being former poultry workers, CWEA’s staff have contacts at the plants and can identify and assist workers who have problems. The center does conduct outreach, and contact workers in their homes, but most workers hear about the center through word of mouth.

The center can help workers in several ways:

Workplace advocacy — We educate and organize workers about unsafe and unhealthy conditions in the workplace. This component of our program enables workers to take the necessary steps to curtail on-the-job hazards and to learn:

• Who is eligible for workers compensation?

• What are your rights as a worker?

• What can be done about wage and hour violations (when workers are forced to work “off the clock”)?

• Who qualifies for company and government disability?

• What’s the difference between sick pay and leave of absence? When do you receive benefits?

• Can I choose my own doctor or do I have to go to the company’s?

Since answers to these relatively simple questions are rarely given to workers on the job, the center helps to fill this void.

Public Policy Advocacy — The center helps communities and injured workers push for legislation that addresses health and safety of poultry workers. For instance in 1989, a staff member of the center testified at a Congressional hearing on the Whistleblowers Protection Act. As a response to her testimony, North Carolina Occupational Safety and Health division and the National Institute of Occupational Safety and Health conducted inspections and found violations at a number of Perdue plants.

Thanks to a recent organizing effort by the center and other workplace safety advocates, Perdue has entered into an agreement with the North Carolina Department of Labor to provide ergonomics training to decrease the number of workers with carpal tunnel syndrome. Although the training doesn’t address the most pressing problem — line speeds — it is an important beginning.

National Poultry Project — This project brings attention to the injustices inflicted upon all workers, especially in the poultry industry. We assist in educating workers and the public locally, regionally, and nationally. We build support for reducing line speed at poultry plants and for correcting the health hazards and life-threatening situations faced daily by poultry workers.

In June of this year we hosted a National Poultry Worker’s Conference in Atlanta, Georgia. Approximately 100 poultry workers, community activists, and consumers began planning strategies for change in national workplace safety legislation and conditions. Representatives from several poultry-producing states attended. A National Poultry Workers Network was developed to address needs for information and advocacy in a more organized manner.

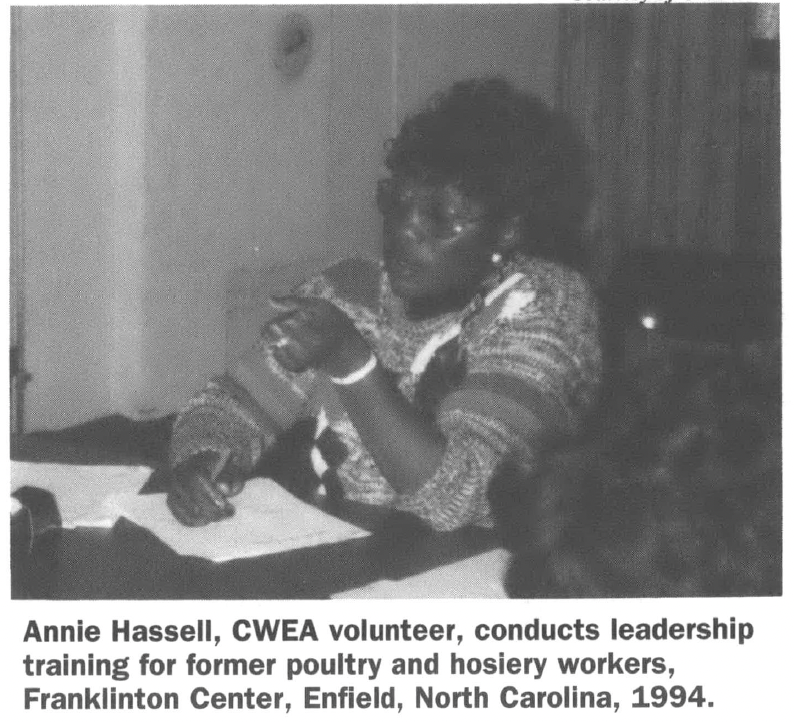

Leadership Initiative — Through a series of training sessions, the Leadership Initiative shows how people may realize their capabilities and use them for improvements in home, school, workplace, and community.

Skill-building sessions enhance self-esteem, expose workers to various types of leaders, and offer an outlet for implementing what they have learned. As a result of participating in CWEA’s leadership programs, three workers have joined the center’s board of directors and three now serve as leadership facilitators.

Injured workers serve as a valuable resource in CWEA’s work with youth. They encourage children to pursue an education so they will not have to work in the plants. Children of injured workers also lend perspective. They describe taking on responsibilities in addition to their homework, getting by on limited income when one parent isn’t working, and the stress of losing their childhood.

The religious community also plays a key role in CWEA’s work. Most of the workers are affiliated with churches in the area and need the financial assistance, emotional healing, and one-on-one counseling that their religious community can provide. Through the churches, the center has raised the awareness of people who are not familiar with carpal tunnel syndrome and the devastating effect it has on the community.

Sometimes the center’s building is simply a place where people can go to feel that they aren’t alone in their struggles. “CWEA is a home away from home,” says Linda Hawkins, a former Perdue worker. Adds Annie Burden, a former poultry worker, “CWEA is there when you need someone who cares.”

CWEA understands that its work isn’t going to change the conditions of workers overnight. But the center is confident that it plays an important role in helping workers to develop a sense of power and control in their communities and lives.

CWEA isn’t trying to close the poultry plants because workers need the jobs. But the center wants to make sure that workers receive a decent wage and compensation when they are injured. CWEA works to see that the next generation of workers doesn’t have the same troubles and injustices found in the plants today.