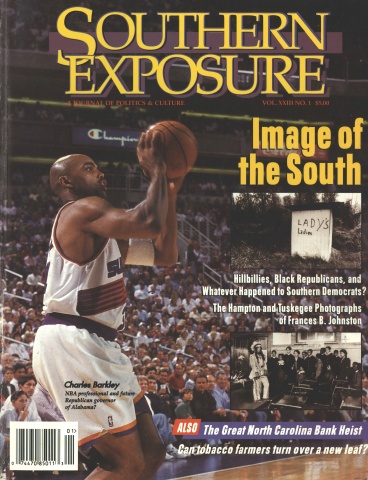

Image of the South

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

What is it about the South? No other region of the United States attracts so much scrutiny and study, so much celebration and derision, so much media hype and misperception. Recent elections, pitting Bill Clinton and Al Gore against the likes of Newt Gingrich, Jesse Helms, and Strom Thurmond — Southerners all, and now all in potent political positions — produce a new urgency for examination of the South and the kind of people who come from the region.

Why does the South need so much explanation? In the 1930s, W. T. Cash wrote about Culture in the South; in the 1940s, W. J. Cash explored The Mind of the South. Much more followed. C. Vann Woodward’s Burden of Southern History, Reed’s Southern Folk, Plain and Fancy, and King’s Southern Ladies and Gentlemen. Even after numerous studies suggesting changes in traditional notions of the South including Egerton’s Americanization of Dixie, other writers such as John Shelton Reed spoke of The Enduring South and, most recently, Dewey Grantham argued, in The South in Modern America, that there is a “persistence of Southern distinctiveness.”

Grantham concluded that cultural patterns in the South — attitudes toward religion and physical violence, musical expression and literary creativity — suggest that, “in spite of drastic change, the South remains the most distinctive region in the nation. Southerners continue to be profoundly conscious of their regional identity.” It is this richness of cultural life and complexity of identity that keeps writers and sociologists, photographers and moviemakers, political pundits and a host of others coming to dip from the endlessly flowing Southern spring and probing the oozy muck underneath.

In this special section, we hear from an assortment of perceptive observers who have been dipping and mucking in the South’s past and trying to divine its future. Edward D. C. Campbell Jr., looks at literal images — photographs — made at the turn of the century by one of those complex Southerners, a woman born in West Virginia, educated in Paris, ahead of her time in feminism, and creator of photographs that encouraged development of a Southern black middle class.

Jerry Williamson offers a wry and witty account of the upland South’s hillbilly stereotype and its serious function in American culture. Writer Jo Carson anguishes over confronting Southern mountain stereotypes as she travels in and out of the South. Researcher Ron Nixon explores the flip side of a common image with his exploration of Southern black conservatives. Finally, Keith Miles, former press secretary for former Senator Jim Sasser (D-Tennessee), ruminates on the political upheavals in the South in the 1994 elections that left him looking for a new job. The writers of these essays, like their subject matter, are all products of the South.

All of these essays in some way confront the issue of cultural hegemony, the notion of who has the power to shape definitions, to set the terms of a community’s or region’s self-understanding. We have learned in studies of the Appalachian South that cultural images of the region have been largely created outside the region for much of this country’s history. Increasingly, improved education, political and economic power, and access to media have given the South more control of its own image-making and now its own cultural analysis.

The regional differences do persist. This was made abundantly clear to me when I learned and told a new joke last Christmas season. The joke goes like this: The three Magi, after long travel, finally arrive at the manger. They are blackened and covered with soot and ashes. Mary asks them, “What has happened to you?” to which the Magi reply: “We have come from afar.” I told the joke to uproarious laughter in Appalachia and in Memphis, but, when I told it to friends from Kansas, they looked at me blankly. I hastily supplied an explanation, so they would “get” the joke, but by then it was a lost cause. If Kansas is the heartland of America, then the South is clearly an extremity — by definition, more radical, culturally “dangerous,” eccentric, extreme, more ripe for rich imagery.

The great Southern writer Eudora Welty wrote that “one place comprehended can make us understand other places better. Sense of place gives equilibrium; extended, it is direction.” While Southerners may seem enamored with our past and compelled to explain every nuance of our culture, our strong sense of place may be our salvation, keeping us grounded and our compass for the future on course. More importantly, in this time of often overwhelming problems regionally and nationally, we may be uncommonly equipped to follow John Todd’s dictum that “elegant solutions will be predicated on the uniqueness of place.”

Tags

Jean Haskell Speer

Jean Haskell Speer, a native Tennessean, is director of the Center for Appalachian Studies and Services and professor of anthropology and folklore at East Tennessee State University in Johnson City. She is author of The Appalachian Photographs of Earl Palmer (University Press of Kentucky 1990) and coeditor of Performance, Culture, and Identity (Praeger 1992). (1995)