This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

During World War II, critic and editor Lincoln Kirstein found a remarkable set of photographs at Lowdermilk’s, one of Washington, D.C.’s old and much-visited bookshops. Although the pictures had often been admired by many of the shop’s customers, no one really knew much about the leather-bound album except that the images had obviously been carefully assembled, numbered, then each protected with transparent paper on which brief captions were written. It was with the help of Grace Mayer, a curator at the Museum of Modem Art in New York, that Kirstein learned he had found a collection of turn-of-the-century photographs of Virginia’s Hampton Institute, most of which were the work of Frances Benjamin Johnston. In 1966, the museum sponsored an exhibition of the 159 original Hampton images, accompanied by an abridged collection in book form. Aside from the intrinsic value of the images he had found, Kirstein might well have been struck, too, by the irony that a predominantly African-American educational institution had hired a middle-aged, white, and Southern woman to photograph its students and facilities.

In April 1949 Life magazine had described the then 85-year-old Frances Benjamin Johnston as the nation’s “court photographer.” For years Johnston had specialized in pictures of the Washington, D.C. political and social elite, and it was solely from that aspect of her career that the periodical’s editors drew samples of her work. When Johnston died in New Orleans three years later, Time magazine echoed the same narrow theme: She had been a “onetime news photographer who had an inside track to the White House because of her friendship with Presidents Harrison, McKinley, and Theodore Roosevelt.”

Born in 1864 in Grafton, West Virginia, Frances Benjamin Johnston grew up there and in Rochester, New York. After her family had moved to Washington, D.C., she studied art at Notre Dame Convent in Govanston, Maryland, and in 1883 embarked on a two-year period of study in Paris’ famed Academie Julien. Back home, she decided to pursue an early interest in writing and was by then a capable artist, contributing her own artwork as illustrations for her first magazine stories. The publishing industry, however, was steadily abandoning the use of zinc line-cut art and moving toward halftone photographic illustrations. Johnston soon adopted what she admitted was the “more accurate medium” — photography.

Relying on a combination of her own skills and her family’s social connections, Johnston for 15 years served as an unofficial photographer of Washington’s social, political, and intellectual life. She captured Rough Rider colonel Theodore Roosevelt posing in his new uniform, just arrived from Brooks Brothers. She took the last “official” picture of William McKinley only minutes before an assassin mortally wounded the president. In the early 1890s a series of her pictures of the White House was published in book form.

Johnston was not overly concerned with photography’s more technical aspects. “I wore out one camera after another,” she once exclaimed, “and I never had any of those fancy gadgets. Always judged exposure by guess.” She, like the far-better-known Alfred Stieglitz, saw photography as more than a straightforward journalistic device; at its best, photography was an expression of artistic sensibility. Thus, despite her clientele and milieu, Johnston was increasingly less drawn to portrait photography for its own sake and began, instead, to bring a studied documentary perspective to her work, especially in the everyday details surrounding her various subjects. This, after all, was the woman who for a circa 1896 self-portrait flouted convention by posing with a cigarette in one hand, a beer stein in the other, and with her leg crossed, ankle on knee, and petticoats showing.

Johnston, like many other female photographers of her day —Jessie Tarbox Beals, Edyth Carter Beveridge, Lillian Baynes Griffin, Gertrude Kaesebier, and Edith H. Tracy — saw the unique opportunities such a profession offered to women. In her essay, “What a Woman Can Do With a Camera,” for the September 1897 issue of the Ladies’ Home Journal, Johnston remarked that the successful woman photographer must have “good common sense, unlimited patience to carry her through endless failures, equally unlimited tact, good taste, a quick eye, a talent for detail, and a genius for hard work.”

Although her reputation had been built primarily on studio and architectural photography, Johnston gradually turned her camera toward photojournalism. The March 1892 issue of Demorest’s Family Magazine included her photo essay on “the innumerable risks and ever-present dangers” faced by Pennsylvania coal miners. She later completed one series of pictures on the Massachusetts shoe industry and another on the District of Columbia’s public schools. In 1899, aided by a note of introduction from the former Assistant Secretary of the Navy, Theodore Roosevelt, Johnston took a series of more than 150 pictures of life above and below the decks of Admiral George Dewey’s Great White Fleet.

It was in that same year that Hampton Institute in Hampton, Virginia, hired Johnston to take a series of photographs intended to capture the school’s mission and day-to-day life. Hampton was founded in 1868 as a coeducational, secondary school for blacks by Samuel Chapman Armstrong, an agent of the Freedmen’s Bureau and a former colonel of United States Colored Troops. First known as the Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute, the school had traditionally stressed a practical, or vocational education and in its first years had been financed with donations from philanthropic and religious groups such as the American Missionary Association. Since 1872, Hampton had also received federal land-grant funds and since 1878 additional federal support for a program for Native American students. The school also relied heavily on outside funding. The photo series was expressly meant to present the institute attractively to the widest possible general public as well as to prospective students and especially to potential donors and employers, black and white.

The school weighed several factors in selecting Johnston for the task. She was, as the institution’s own Southern Workman and Hampton School Record called her, “an artist of high rank.” She was also near at hand and, more important, fairly well known for her photographs of the workaday world: of laborers, their tools, and their surroundings. The institute was also aware of her “excellent work” in photographing student life within the Washington, D.C., schools. Johnston’s rates, moreover, were less than those of many other skilled photographers — in part because she was a female trying to make her way in a profession still overwhelmingly male, and in part because she sometimes paid less attention to the business side of her art than was always prudent, whatever the competition.

Johnston and an assistant arrived at Hampton in November of 1899 and for at least the next several weeks took pictures of the campus and classroom life. Each finished image — what Johnston chose to show, how she posed her subjects, even how she framed an image — carried with it unique aesthetic and technical demands, primarily because Hampton Institute hoped each view would meet a particular cultural need and social philosophy. Indeed, Johnston’s work was to be both a documentary record of the campus at the turn of the century and, more important, a response to the debate on what direction black-white relations, and black education, should take.

Since its founding, Hampton Institute had debated the effectiveness of what by the turn of the century had become widely known as the “Hampton idea” — the concept of “industrial” or “vocational” education for blacks as opposed to an academic or business curriculum. Although he had first supported schooling primarily in farm and other labor skills, Samuel Chapman Armstrong by 1872 had seen the value of a strong academic course of study. After Armstrong’s death in 1893, Hampton Institute reassessed its mission. Four years later his successor, the Reverend Hollis Burke Frissell, declared that thereafter “the academic department is now made the stepping stone to the industrial and trade work.” By then similar educational philosophies had spread to other schools and, indeed, had become closely identified with Booker T. Washington.

A Hampton graduate and founder of Tuskegee Institute in Alabama’s black belt, Washington argued that the “Hampton idea” could revolutionize a rural South plagued by black poverty and illiteracy. Southern white leaders for years had been extolling the benefits of a “New South,” one driven by a diversified economy. Schools such as Hampton and Tuskegee, Washington and his followers believed, should take advantage of the change and push a vocational curriculum expressly designed to produce capable farmers, bricklayers, carpenters, draftsmen, or factory workers. Other black leaders, such as W.E.B. DuBois, protested the narrow emphasis on trade over academic education and on economic over social and legal equality, pointing out that both paths only reinforced white efforts to keep the black population politically subservient and economically dependent. In response to such warnings, Washington replied that for the present at least “the opportunity to earn a dollar in a factory just now is worth infinitely more than the opportunity to spend a dollar in an opera-house.” Thus every picture Johnston made of Hampton’s students and classrooms was by its very subject a statement in an ongoing debate.

In January 1900, within weeks of her arrival, the institute’s Southern Workman outlined how Johnston’s work would be presented that year to an international audience at the Paris Universal Exposition. The school’s plan was that Johnston’s photographs would both reinforce “the importance placed by the school authorities on the training of the Indian and Negro in the arts that pertain to home and farm life,” and portray how “every part of the school life bears upon the home and the farm.” Even before using the pictures for the Paris exhibit, the school planned to convert the images to slides so that “friends of the school” could attend “stereopticon lectures in New York, Philadelphia, and Boston” that winter.

Johnston’s pictures for the exposition were also to be part of a very limited American Negro exhibit, designed to present a view of “Negro progress and present conditions” but subsumed within numerous other and much larger presentations on the United States as a whole. In the entire American Pavilion, the commission had allotted only about 12 square feet of exhibit space to the theme of black life; thus photographs — as opposed to student projects and products or teaching materials, for instance — were ideal. It was Thomas J. Calloway, a young black appointed as a “Special Agent” by the commission, who devised a system of cabinets for displaying pictures from both Hampton and Tuskegee Institutes and from Fisk, Howard, and Atlanta Universities.

Johnston was in Paris attending the Third International Photographic Congress, scheduled to coincide with the exposition. Johnston spoke to the conference, in French, on the work of artist-photographers in the United States. It was not her lecture, though, but her photographic work which generated the most interest — and garnered several awards, including the Grand Prix. Calloway reported that the Hampton images were regarded as “the finest photographs to be seen anywhere in the exposition,” and that “it was the general opinion that nowhere had the photographer’s lens been so eloquent and impressive in the story of a great work as was silently narrated by these photographs.”

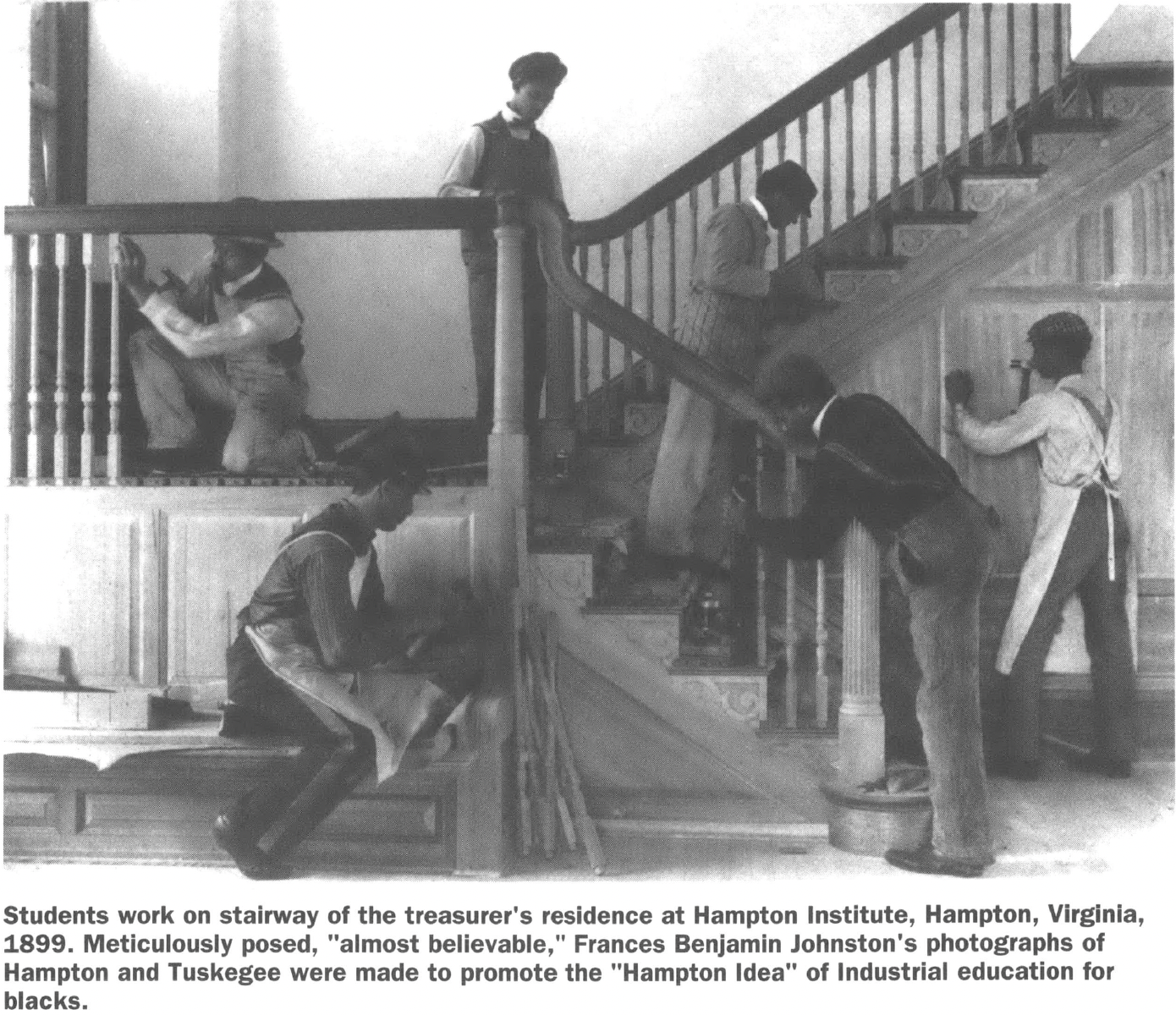

Johnston’s pictures meticulously idealized the “Hampton idea.” John Szarkowski, director of the Museum of Modern Art’s photography department, in commenting on the Hampton photos, remarked that Johnston was a stern taskmaster: “In her photographs no head or hand moves during the long exposures; no undisciplined individualist clowns for the camera; no property, no matter how interesting in itself, is allowed to violate the taut, flat planes of her compositions.

“She ordered life,” he added, “to assume a pose that conformed to her own standards” — and to the “Hampton idea” as well. In each image the carefully posed students are hard at work absorbing the institute’s straightforward education. Thus, although there are photographs of pupils studying the poems of John Greenleaf Whittier or the cathedral towns of Europe, there are far more images of students involved in more utilitarian work: animal husbandry, bricklaying, carpentry, dairy science, domestic service, dressmaking, mechanical drawing, metalworking, and shoemaking. Even in the arts and sciences, the applications were on the practical: classmates in a physics laboratory study “the screw as applied to the cheese press,” while young artists gather in a field to sketch “agricultural work,” and mathematics students study the proportions of a brick staircase with the assistance of “a student mason.”

To her initial images of campus and classroom life, Johnston added another series of photographs comparing the comfortable life of Hampton alumni with the harsh, poverty-stricken rural existence to which many other blacks were condemned. That way, as the Southern Workman reported, “the old-time one-room cabin and the old mule with his rope harness, just tickling the ground with a rusty plough, will be contrasted with the comfortable home of the Hampton graduate, the model barn, and the team of strong horses making a deep furrow with a heavy plow.” Johnston took the latter views in the Virginia countryside near Hampton, pitting “The Old Folks at Home,” “The Old Time Cabin,” and “The Old Well” against a Hampton graduate’s family seated in a formal dining room or “three Hampton grandchildren” gathered about a modern backyard well.

Johnston’s photos, as James Guimond pointed out in perhaps the most perceptive analysis of the Hampton Album, strongly implied that the students were dutifully learning “the white man’s way.” The series, Guimond added, “was probably one of the first attempts to use photography to document the application of the American Dream of prosperity and progress to the nation’s minorities — in this case to the blacks and Native Americans who were students” at Hampton in the autumn of 1899. Every class and recreational group, the men usually attired in uniform and the women in starched pinafores, is arranged “in poses that are replicas of the group photographs made at white colleges and universities.” Lincoln Kirstein described the same views as “frozen . . . habitat groups,” as groups “almost, but not quite entirely — believable.” More to the point, the photographs presented a “white Victorian ideal” as the “criterion towards which all darker tribes and nationals must perforce aspire.”

At the time, however, the response was overwhelmingly positive. Hampton Institute, for example, initiated a series of essays in its Southern Workman featuring the Johnston photos. Moreover, 41 of the Paris exhibit’s photographs were published in the April 1900 issue of the American Monthly Review of Reviews and the collection as a whole was exhibited at the 1901 Pan American Exposition in Buffalo. It was perhaps no surprise to Johnston that she received a letter from Booker T. Washington in the summer of 1902 about her work. Only the year before Washington had dined with Theodore Roosevelt at the White House, to the considerable discomfort of most white Southerners, and seen the publication of his autobiography, Up From Slavery. Washington wanted a photo portrait of himself and for Johnston to do for Tuskegee what she had for Hampton.

Johnston wrote from Atlantic City in August with an approximate idea of what the work at Tuskegee might entail and cost. Assuming that Washington wanted her “to cover every phase of the life and training there” and that he needed prints “both for exhibition and publication,” Johnston proposed “the same terms as I received at Hampton”: that is, for a thousand dollars, plus “the living expenses of myself and assistant, with our transportation from Washington to Tuskegee and return,” she would “fully cover your Institution and its work estimating 150 to 175 8x10 plates for it and furnishing you four complete sets of prints, one set on platinum paper mounted for exhibition.” “Incidentally,” she added, “I will leave your negatives filed and cataloged, and doubtless during my stay I could train some of your young assistants to make such prints as you might require in [the] future.”

Johnston eventually made two trips to Tuskegee, the first one in 1902 and another in 1906. It was her first that attracted attention, and proved a harsh reminder that beyond the confines of a Hampton or Tuskegee campus, the realities of Southern life could be quickly encountered. As part of her work, she was supposed to photograph several of the smaller industrial-education schools popularly known as “little Tuskegees.” In late November, Johnston took the train to Ramar, Alabama, where she was met by Henry E. Nelson, a graduate of Tuskegee and principal of the Ramar Colored Industrial School, and two of his associates. On the same train was George Washington Carver, the head of the agricultural department at Tuskegee. That Johnston, a white female, had arrived in a small Southern town, after dark, accompanied and met by black men led to what Carver later recollected as “the most frightful experience of my life.”

Carver, in fact, had wondered “whether I would return to Tuskegee alive or not.” Carver believed that somehow “the white people evidently knew” Johnston was coming. Once there, she and Nelson boarded a buggy and drove off into the night for Nelson’s home, several miles away. When Johnston realized how long the trip might take, she decided it might be best to return to town and find a hotel room. By the time they got back, though, it was already eleven o’clock. Before they could reach the hotel they were accosted by two men, a fellow named Armes, who was regarded as “something of a desperado,” and another man, identified only as the son of the local postmaster, George Turnipseed. The former fired three pistol shots at Nelson, who fled for his life. Johnston somehow made her way to where Carver was staying and it was Carver “who got out at once and succeeded in getting her to the next station where she took the train the next morning.”

By daylight, the white community was in an uproar. There was already a mob looking for Nelson, who quickly fled to Montgomery. Carver spent at least one night wandering the countryside, trying to stay out of view. The Ramar school itself, “was patrolled by a white man walking up and down in front of the school house with a shot gun.” As Carver wrote Washington on 28 November, Nelson had done “great work there and it grieves me to know he must give it up.”

Johnston, however, was not quite finished. Indeed, Carver thought she was “the pluckiest woman I ever saw.” Threatening to file a suit against the two attackers, she went to Montgomery to protest and, if she could not get to her attackers directly, even threatened to have her friend, President Roosevelt, fire the town postmaster. The governor, William D. Jelks, listened but could only offer that they “must face the facts and consider the locality and the people we were dealing with.” The local sheriff was sympathetic, and even complimented Nelson’s work in the community. In the end, though, the white men never faced punishment, the school closed, and Nelson had to move. He did eventually open another institution in China, Alabama. Johnston completed her work, photographing the “little Tuskegees” at Mount Meigs and Snow Hill, Alabama. Thirty-two of the photographs of Tuskegee and the other schools appeared in the August 1903 issue of the World’s Work with an essay by Booker T. Washington, “The Successful Training of the Negro.”

Following her Tuskegee series, Johnston apparently became less interested in portrait photography and photojournalism and turned toward garden and architectural photo work. From 1913 to 1917 she lived and worked in New York City and by the 1920s had become a popular lecturer on gardens. But she had never completely abandoned the South. After collaborating with Henry Irving Brock on a 1930 book, Colonial Churches in Virginia, she received a $26,000 foundation grant for what became known as the Carnegie Survey of the Architecture of the South. Throughout the ’30s, Johnston traveled across the region. Perhaps influenced by her earlier work in the Virginia countryside around Hampton and in rural Alabama, she avoided the larger 18th and 19th century homes — which, she proclaimed, had already “been photographed often and well” — and instead looked for structures reflecting “everyday life”: “the old farm houses, the mills, the log cabins . . . the country stores, the taverns and inns.” Much of her work appeared in studies of the early architecture of North Carolina (1941) and of Georgia (1957). In 1947, Johnston donated a huge collection of correspondence, prints, and negatives to the Library of Congress. The library in 1953, a year after her death, purchased additional materials from her estate.

Johnston had difficulty achieving the fame she deserved outside her profession and a relatively small circle of appreciative curators and architectural historians. In a December 1935 profile in the Richmond Times-Dispatch, Johnston related an earlier conversation with a female reporter. “In due time,” she remarked, “the young lady arrived. I assumed, of course,” Johnston continued, “that my interviewer had some idea of my work, or that she had some reference clippings before she started which would make her at least conversant with my objectives. Imagine my chagrin when after going industriously through a score or more of my pictures, my young caller exclaimed: ‘Oh, Miss Johnston, these pictures are marvelous! Who does your photography?’”

At her death in 1952 Frances Benjamin Johnston was still best known for her photographs of Washington society. The rediscovery of her Hampton and Tuskegee images have since then renewed critical interest in her photographic art. There is no doubt, too, that they offer a profound glimpse into the debate that raged among black leaders and educators as to how African Americans should make their way in the South of the early 1900s. There is no doubt, either, how important Johnston’s images were to her employers and their students. “Outside of Hampton,” Lincoln Kirstein observed, “there is an ogre’s world of cruel competition and insensate violence.” But within the idealized educational environment Johnston so carefully constructed and forever fixed in time, “all the fair words that have been spoken to the outcast and injured are true. Promises are kept. Hers is the promised land.”

Tags

Edward D.C. Campbell Jr.

Edward D. C. Campbell Jr. is a member of the Publications Division of The Library of Virginia, Richmond. (1995)