This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 23 No. 1, "Image of the South." Find more from that issue here.

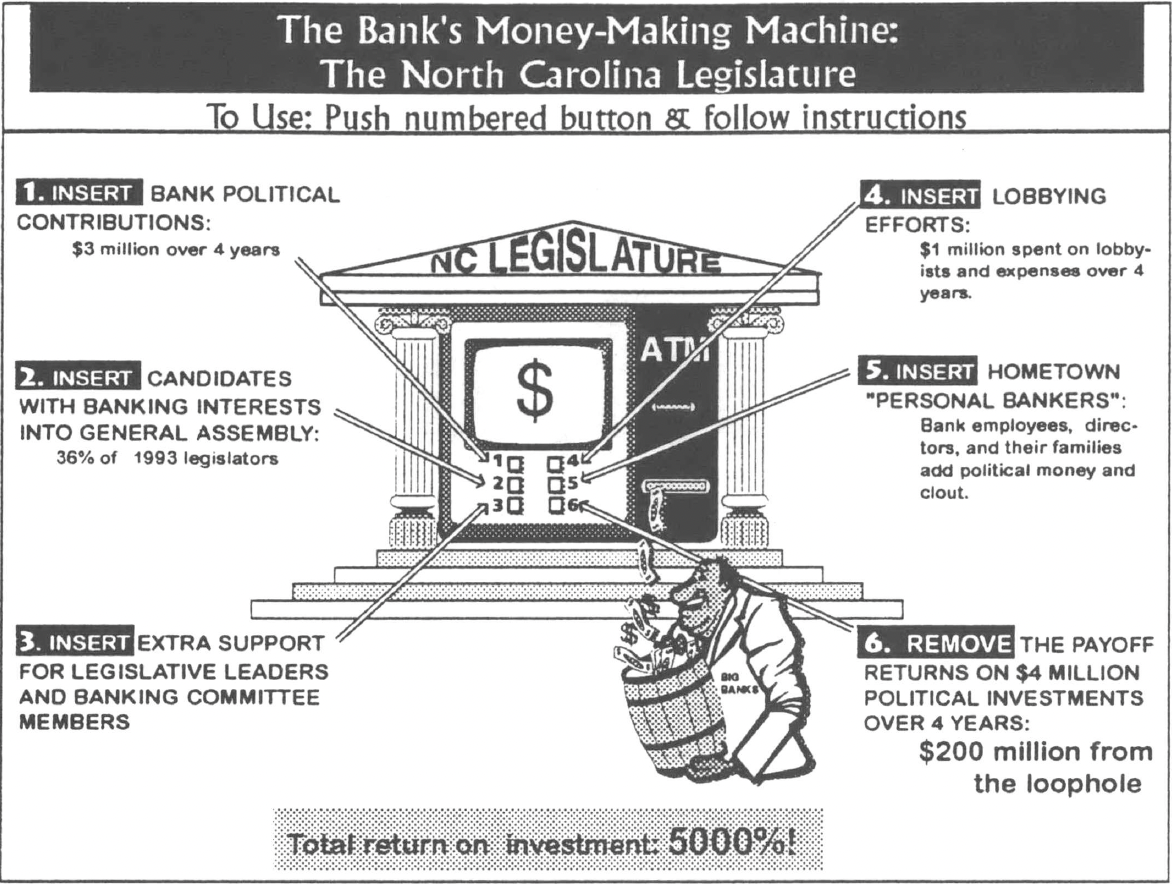

Forget precious metals. Get rid of those mutual funds. For a real return on your investment, put your money in political influence.

That’s the strategy North Carolina bankers follow — and it’s paid off handsomely. Consider the example of the state’s fifth largest bank, First Citizens. It earned $42 million in 1990, and because of a tax loophole provided by North Carolina lawmakers, First Citizens paid nothing in state income taxes. Not a dime.

The tax loophole saves North Carolina banks over $50 million each year — and to help keep it in place, banking interests annually invest $1 million in political donations and lobbying. The investment’s return: 5,000 percent!

The loophole lets banks pay no income tax on the earnings from U.S. bonds and also deduct from their taxable income the cost of depositors’ money used to buy those bonds. In 1992 and 1993, an old-school Democrat tried to close the banks’ loophole. “People told me, ‘You’re messing with the gorilla,’” recalls John Gamble, a 73-year-old state legislator from conservative Lincoln County.

William Baker, who heads the North Carolina Revenue Department’s corporate tax section, admits the loophole “doesn’t make sense from the state’s point of view or for the taxpayers who don’t get this privilege.”

An accounting firm hired by the legislature found that North Carolina’s big banks pay nearly the lowest income tax rate in the nation and less than one-fourth the rate paid by the typical Mom-and- Pop business in the state. Despite the experts and the evidence, Gamble’s bill to close the loophole never got out of the House Committee on Financial Institutions. Why?

Goodwill Bundles

The Institute for Southern Studies recently investigated the $50-million tax break and other bank privileges. The report, “Bank Heist,” provides a case study of how private money has poisoned the political process, forcing ordinary taxpayers to subsidize wealthy interests that can afford to invest in politics.

Here’s an overview of how bankers invest in political influence:

Campaign Contributions

By bankrolling promising candidates, banks win the allegiance of elected officials. From 1989 through 1992, banking interests gave about $3 million in campaign donations to state-level candidates and political committees. Only the broader-based health care and real estate industries funneled larger amounts to politicians.

Ten bank-related political action committees shelled out $466,000 to 159 of the 170 state legislators elected in 1992. More money came from bank directors, such as First Citizens’ top stockholders Frank and Lewis Holding, who gave $22,564 over four years.

The banking industry’s 40,000 employees also offer fertile ground for “bundling”; for example, a Wachovia lobbyist presented the state treasurer’s 1992 re-election committee with 179 checks from company executives worth $9,300 — more than twice the limit of a PAC contribution. The treasurer strongly opposed Gamble’s anti-loophole bill.

Hired Lobbyists

“Giving political contributions is an entree into [legislators’] offices,” explains Zeb Alley, a lobbyist whose clients include the North Carolina Banking Association. In the past three legislative sessions, banking interests reported paying lobbyists $457,000.

Lobbyists make their clients’ views known in committee meetings and — more frequently — in informal settings where far-from-home legislators rely on them for food, drink, and friendship. Most of what lobbyists spend remains unreported, but sometimes a glimmer emerges. In 1992, lobbyists for the North Carolina Bankers Association reported spending $790 feeding and entertaining Thomas Hardaway on 10 visits to Vinnie’s Restaurant and a popular country club. It was the same year Hardaway chaired the House committee that oversaw most banking legislation.

Bankers on the Inside

Banks encourage their executives to get involved in civic affairs, build relationships with policy makers, and recruit them onto local boards of directors. More than one third of the 1992-93 legislators had significant economic interests in banking. Fourteen of the 50 state senators either served on bank boards, or they or their wives worked full time for banks. Another five listed themselves as attorneys for banks.

The 1993 House Committee on Financial Institutions that killed Gamble’s anti-loophole bill included vice chair George Holmes, a director of First Union’s Yadkinville branch; Bob Hunter, whose wife is a director of First Union’s Marion branch; Jerry Dockham, a director of Central Carolina Bank in Denton; Walter Church, chief executive officer of SNB Savings Bank; Tim Tallent and Julia Howard, who list themselves as doing real estate appraisal work for financial institutions; vice chairs Mary McAllister and Ronnie Smith, who disclose substantial stock ownership in United National Bank and Centura Bank, respectively; and John Nichols, president and major stockholder of 1st Choice Mortgage Corporation.

Rewards for Loyal Incumbents

By supporting legislators who have done their bidding, banks help their friends gain seniority and get appointed to key committees. The top two recipients of bank money on the Senate banking committee were its chairman (a BB&T director) and an incumbent who faced a tough re-election campaign.

Bankers gave $8,800 to House Speaker Dan Blue’s 1990 and 1992 campaigns, plus $12,000 for his 1991 and 1993 receptions. Blue assigns bills to committees. “As a tax bill, my bill should have gone to the Finance Committee,” Gamble claims. “My bill was as good as dead when Blue assigned it to the Banking Committee.”

The Hometown Lobby

The bank lobby mobilizes an army of “personal bankers” — local employees who push its agenda in every legislator’s home district and who reap immeasurable “goodwill” by donating to local arts councils, colleges, United Way drives, and other area charities. Representative Gamble believes hometown pressure was the banks’ most lethal weapon against his bill. “When you go home, your personal friends come to see you and tell you how this bill will destroy the banking industry,” he says. While the Christian Coalition uses hot-button emotional issues, banks gain loyalty by spreading cash around — or withholding it at key moments.

Merged Interests

Connie Wilson, a NationsBank trust officer and state legislator, describes bankers’ political gifts as “civic-mindedness.” Lawmakers insist they cannot be bought. Indeed, a review of policy debates reveals that most legislators don’t distinguish between public and private interests; to them, what’s good for banks is good for the state.

“The question is: What kind of business climate are we going to have in the state?” says House financial committee member Larry Justus, a Republican. “Having banking laws more in line with other states would take away North Carolina’s advantages.”

“Legislators I’ve talked to are proud of the North Carolina banks,” says 1993 Senate Finance Committee chair Dennis Winner, a Democrat. “They are a great economic benefit to the state.” On his economic-interest statement, attorney Winner lists himself as on “retainer” with at least one bank.

In such a subservient legislative climate, the biggest North Carolina banks have thrived. The state legislature has allowed banks to engage in branch banking, Southern regional mergers, and now national interstate banking. NationsBank has grown into America’s third-largest bank, a colossus with 1,900 branches in nine states and $171 billion in assets. First Union and Wachovia have also ballooned; the top six banks now control over 80 percent of deposits and loans in North Carolina.

While big banks expand, the losers are small businesses and average citizens who pay more taxes and have a harder time getting loans at reasonable rates. Reports cited in “Bank Heist” reveal that banks fail to provide access to credit, even though they get cheap money from the Federal Reserve and from depositors protected by federal insurance. The chief accountability tool local activists have — the Community Reinvestment Act — may soon be gutted by Republicans in Congress.

The ability of bankers to get favorable laws will only increase as the cost of campaigns climbs and candidates become more dependent on big contributions. Ironically, if the North Carolina legislature closed the $50 million loophole for banks, the new revenue could provide public financing for all candidates for governor, council of state, and the legislature — with more than $40 million left over. Mention of public financing brings cries of “welfare for politicians.” But when wealthy contributors pay the price, they put politicians in their debt and reap their own brand of welfare — like the banks’ tax subsidy. By closing the loopholes, voters could “own” their government and still save on their tax bills.

The full “Bank Heist” report by Calvin Allen, Lisa Hamill, and Bob Hall, is available to Institute for Southern Studies members for $10 ($35 to non-members). To order, fill out coupon in magazine and attach with payment — or send check to Institute for Southern Studies, P.O. Box 531, Durham, NC 27702.