A Second Chance

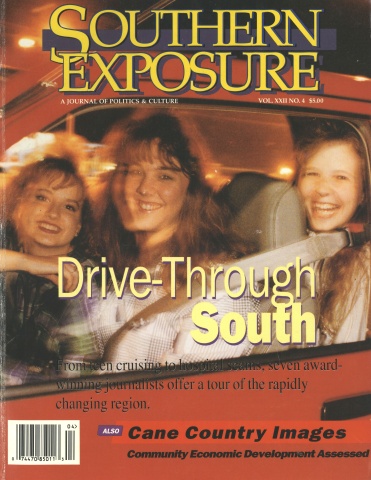

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 4, "Drive-Through South." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

Florida officials showed little concern when reporter Sally Kestin began investigating cases of children who were molested, sexually assaulted, or raped in foster homes and shelters for abused children. The problem, they insisted, was not widespread.

Kestin’s series of stories proved otherwise. By the end of her investigation, one top official estimated that at least 9,000 young sex offenders and 11,000 abuse victims in Florida were not getting the help they needed. Her reporting led to firings, transfers, and reprimands at the state Department of Health and Rehabilitative Services — and prompted legislators to improve tracking of abuses and treatment for victims and offenders.

Carrabelle, Fla. — Steve fidgets in a chair in his counselor’s office and talks optimistically about the future.

“I want to be a cop, a fireman. I want to be everything. There’s just so many choices.”

That view of a world filled with possibilities wouldn’t be so unusual coming from any other 16-year-old. But two years ago, Steve couldn’t read or write. The only thing he had mastered, while growing up in an impoverished, unstable home in Miami, was how to break into houses.

He wound up in a psychiatric hospital for troubled youths in this gulf-front town in the Panhandle after breaking into a home, terrorizing two children, and forcing one of them to commit a sexual act at gunpoint.

Steve’s crime and background were so heinous that they caught the attention of several attorneys and Jim Towey, then head of the South Florida region of the state Department of Health and Rehabilitation Services (HRS). Towey contacted hospitals in and out of Florida, trying to find a place that specialized in sex-offender treatment and would take Steve, whose real name is not being disclosed in this report to protect his identity. After several months of searching, Towey convinced the president of Inner Harbour Hospitals, a group of non-profit psychiatric hospitals, to take Steve on at a reduced rate.

Now, nearly two years later, Steve is reading at a sixth-grade level and talks about the remorse he feels for the pain caused by his life of crime and sexual offenses. “Every day, I say, ‘stupid fool,’” he says, embarrassed to be talking about it with a stranger.

He would rather focus on the positive: “I’m excited about myself and the progress I’ve made. I want to do everything right, now. I want to go to school and get my education.”

Thousands Lack Treatment

Though it is too soon to declare success, Towey — who was named to head the HRS last year — says that Steve at least has a chance to turn his life around. It’s a chance that thousands of other young sex offenders in Florida never get. “He’s obviously a changed kid,” Towey says. “I’m hopeful.”

Apart from Inner Harbour Hospital, which has six youths in its sex-offender program, Florida has only one other treatment center for young offenders. But that institution, the Elaine Gordon Treatment Center in South Florida, can take just 22 juveniles.

HRS and mental health therapists estimate that there are thousands of young rapists and molesters in Florida, most of whom were sexually abused themselves. And without treatment, it is feared, the number of victims will continue to grow, perpetuating the cycle of abuse.

The legislature included $2 million for treating juvenile sex offenders in the juvenile justice package passed last week. Critics say that treatment is expensive and doesn’t have proven results. It costs $236 a day per child at the Elaine Gordon Treatment Center and $290 at Inner Harbour.

Towey says the investment is worth it, “particularly when you look at the alternative, which is much more expensive when they’re in adult prisons at $50,000 or $60,000 a year.”

Steve says he would have continued molesting other children if he hadn’t been caught. His older brothers, an uncle, and a social worker sexually abused him. “Other people were doing it to me so I started doing it,” he says.

He molested his younger brother. He fantasized about molesting hundreds of girls and boys. He hadn’t planned on molesting the child that he unexpectedly found in a home he was burglarizing.

Burglary was another habit that he picked up from his older brothers. When he was just six years old, they would hoist him through windows to steal “whatever you could grab.”

An Open Door

But on that September morning in 1991, Steve cased a house and decided to break in by himself. He says he wanted money to go to a party in Miami Beach. But when he got to the house, he was surprised by two boys, one about 10 and the other seven. They were out in the yard playing when he arrived.

Steve pointed a flare gun that he had stolen and then smashed it down on the hand of one of the boys, who was trying to hold the gate shut. Frightened, the boy ran into the house and locked the door. Steve says he conned the boy into opening the door by promising to leave if he could have a glass of water. Once inside, however, Steve asked the boys to show him where their parents kept jewelry. They didn’t cooperate.

“The older brother got smart, so I whacked him across the head,” Steve says. The younger boy defied Steve’s orders to stop screaming, and Steve locked the child in a bathroom.

“I was getting real aggravated, irritated,” Steve says. “I grabbed the older one and took him in a closet” and forced him to perform oral sex.

“They were ruining my plan,” Steve says. “If they weren’t there, none of this would have happened. When I saw these kids, a hundred different plans came through my mind.” He thought of tying them up. He even thought of killing them.

At the time, human life didn’t have much value to Steve. He lived with his mother and grandmother, who had medical problems and were trying to support him, his three brothers, and six cousins. He had run away several times. Often, he would venture “as far away as possible,” even sleeping in parks to get away from home.

Steve viewed the home he broke into as an opportunity. “Everything I wanted was in there,” he says.

His education consisted of one week in the third grade. He says he vowed never to return after a teacher forced him to read in front of the class, a task he could not perform.

He was repeatedly picked up by police, and at one point spent 16 months in a juvenile detention center. His brothers were in and out of jail. Since he’s been in Inner Harbour, he’s talked to one of his brothers during a hiatus from jail. But his mother and grandmother have apparently moved. They never attempted to contact him.

Since he has no family to live with, social workers are trying to arrange for Steve to go to a group home in Tallahassee when he is released from the treatment center this summer.

He is looking forward to enrolling in school, getting a job and eventually settling down and having a family. “Four years ago, all I saw was going to prison, getting out, going to prison,” he says. “It was a door that was blocking the other view. Now that I’m here, I can see that door is open and I have all these choices.”

He says he knows that people will be skeptical of his rehabilitation. “I can’t say, ‘Step into my future and see I’m not going to do this,’” he says. “I can just show them with my actions.”

Other Winners

For youth reporting in Division One (circulation over 100,000)

Second Prize to Beth Macy of the Roanoke Times & World-News for systematically examining the causes and consequences of teen pregnancy, and for going beyond the numbers to tell the human story of pregnant teens and young mothers.

Third Prize to Ron Hayes of The Palm Beach Post for opening the pages of the newspaper to a group of youth too often shunned and silenced — gay teens.

Tags

Sally B. Kestin

Sarasota Herald-Tribune (1994)