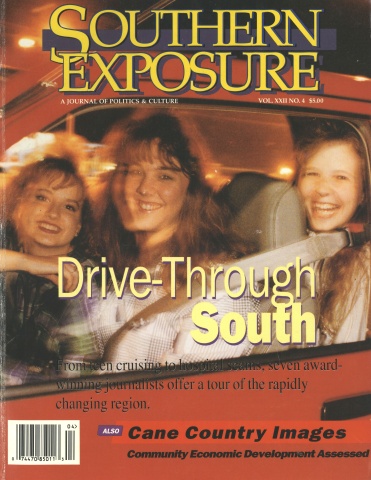

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 4, "Drive-Through South." Find more from that issue here.

He sat high on the wooden bleachers, a tall, stooped man with silver hair, squeezing his domestic beer can into the shape of an hour glass. If, like the doctors said, he was running out of time, Lewis chose to forget it. He only knew he didn’t want to go home to supper. He wanted no part of greeting Maggie’s brother or the anemic wife and pack of coyotes they called children. He could hear them howling a block away, clear to the park, and imagined them scattering out of the silver new Mercedes Benz station wagon with yellow comic books, howling at a moon that didn’t want them. Lewis supposed he would live without meatloaf. His heart would thank him.

In the clearing behind the dugout, a group of teenagers passed a cigarette and thumped their feet in the dust to the beat sounding from an enormous radio propped on a handle of the seesaw. Wild-eyed and quick, they seemed curiously unhappy despite a show of playful shoving and laughter. Lewis knew these kids wouldn’t let suppertime or the breeze, the hush of shadows, perform the usual exorcism. Tonight, a Friday, they would stay, bring the devil into the dark and grip him.

He pulled the tab on his last can of beer and wrapped his lips around its upshoot of foam. When he looked up, he spotted Travis, his nephew, sulking by the chain link fence, the sun a pinkish, steel-gray smear behind him. Travis wore the same brown corduroys, now threadbare, that had already a year ago begun exposing his bony ankles. Lewis wondered, why for all his newly amassed money, the boy’s father wouldn’t break down and buy the kid a decent pair of trousers. The sight of his nephew flicked a switch in Lewis’s brain, set him thinking how the years pass and how he’d spent thirty-four of his own driving a bus for the city. For all his determined silences, Travis seemed to have no ambition, no moxie, and yet that narrow boy’s stare — assessing him last Thanksgiving over the pages of a science fiction novel — professed to judge him. Lewis had nothing to be ashamed of. He had dedicated his life to supporting things: his wife, a mortgage, the precious tank of exotic fish he collected and replenished for years before losing patience with loss and flushing them away, the last of the slippery dead. He’d supported an ornery solitude, too, easy as dreamless sleep, as that hypnotic ring of colored fish drifting slowly forward, slowly back.

He swallowed some warm beer and watched his nephew approach the bleachers. The letters, careful script on fussy stationery, said Travis planned to attend Columbia University when he graduated high school, that he would study microbiology or something. His sisters called him “techie,” with contempt. Lewis watched him climb the bleacher steps and set his wilted-looking body down on a lower bench. “Hello, Uncle Lew.”

“’Lo, Travis.”

“Aunt Margaret says come to supper now. She sent me to find you. Dad wants you to see his new car.”

“I’ll be along. I doubt your father bothered to tell you, but a man should finish what he starts.” Lewis displayed his beer can. “Unless you want it. You’re the guest after all.”

“No, thanks. I don’t drink on week nights.”

“But you do weekends?” Lewis demanded.

“Occasionally. At a dance or something.”

“You go to dances?”

“Occasionally. If I feel like it. If there’s a good band playing.”

“A regular Prince Charming, my nephew.”

“Uncle Lew,” he reminded him. “Everyone’s waiting.”

They sat in stubborn silence a moment, Travis eying the group beyond the dugout with blank, hazel-specked eyes.

“If you walk back with me, I could show you the car.”

“I saw the car in the picture your mother sent.”

“It’s better in real life.”

“Real life? I can’t imagine anyone in real life paying that much cash for a lousy wagon. If you’re spending for a Mercedes, least you can do is buy a nice model, a sports model. Otherwise it’s a waste, seems to me.”

“That’s fine if you don’t have family,” Travis said pointedly, a slippery, entreating expression on his face. “That’s fine if it’s just two of you.” He sat back down but gingerly, as if the bench might be unstable. “I understand you’ve seen the doctor again?”

Lewis winced. He formed a sudden image of the whole pack of them circled hungrily around a cooling feast, howling perhaps and banging the ends of Maggie’s bent wedding silver on the table, Maggie whispering about his “condition.”

“Should you really be drinking?”

“No.” Lewis startled even himself with his ferocity. The group at the dugout froze in their antics to look them over; a mob stare, laced with malice. Travis didn’t flinch, staring past his uncle as if the conversation was a formality and Lewis was already dead. “No, I shouldn’t be drinking, but I do and will go on doing, and I don’t appreciate people policing my diet, Travis.”

“I’m trying to help.” He made his way laboriously down the sloped bleachers. When he reached the bottom, Travis paused and looked back. “I’ll tell them I couldn’t find you.” Lewis shifted on his bench, pinned in a moment of gratitude.

The boy strayed off, slapping at a mosquito. Lewis watched him go, and so did the crowd at the dugout. Lewis didn’t pay much attention when a section of the group broke gradually away, like a cell dividing, to drift after his nephew. He shut his eyes to the breeze and realized with a sense of melancholy and regret that he was hungry. If the beer and relative quiet had lasted, Lewis might have sat up there on the bleachers till dawn. He’d done so in the past, to imagine the crowd’s roar as he sauntered past home plate, the ball he’d whacked lost in a patch of elms far beyond the field. Or to lose himself, literally forget himself by entering a sort of trance there on the bench. Nothing could harm him then, no memory or anxiety would penetrate his armor. He couldn’t do it, don the armor, if he made a conscious effort, and he couldn’t prolong the magic if distracted by his rough hands and frayed cuffs, the gas in his stomach, if he ran out of beer or acknowledged a need to urinate. On Friday and Saturday nights the neighborhood kids took over this spot, drinking and carousing, and their shrill obscene voices, approaching from all sides now and shifting angles like echo, panicked him. He thought of the beer back in his refrigerator, that if he doused it in ketchup a slice of Maggie’s infamous meatloaf might not sit too heavy with him.

He took his time. Lewis mostly took his time about things now, the doctors had told him to, and he paused as if listening to a distant trumpet at the edge of the field by the path. A bird or two screeched out of the brush, and a voice giggled. Lewis trudged on, trying not to determine what the neighborhood cretins did in that thick patch of bushes after dark. Copulated probably, there on the edge of the park, right down there in the dirt.

When he looked, he didn’t see faces anymore, except the pretty ones sometimes, underage girls in short tight skirts under liquor store neon searching the faces they found for signs of softness of character, for someone to purchase their beer or apple wine or their sticky sloe gin for them. He studied them sometimes as if to answer a question, as if to seek a solution in faces that should have been innocent. Once he gave in to the pleas, bought a pair of them a six-pack. The willowy one kissed him on the cheek when he returned with their change, said: “Keep it, gramps,” and sauntered away with her friend. They left Lewis there rubbing his stubbled cheek, and rubbing it, afraid.

When he walked in, the two young coyotes were stretched out on the parlor floor in front of the television. They were absorbed in a music video in which three beastly looking youths in black leather were lowering a fourth into a spitting pit of fire. Before they could release him, drums accelerated and the scene flashed on to another—a bright field of wheat that could have been Kansas — with the doomed fourth youth, the singer, busy slobbering over a girl on a picnic blanket. She wore a straw hat and nearly transparent dress and to spite the hat wore lipstick the color of bruises; overall she looked more inclined to turn a trick than sit all the sunny afternoon long slurping watermelon. Lewis scowled. Neither of the girls said hello. Nobody said anything. The entire house, in fact, was a hush.

In the kitchen, Maggie and her brother’s wife sat back from the table with coffee mugs. “Well, there they are.” Maggie popped out of her chair like a jack-in-the-box and slid the pan of meatloaf from the oven.

“I told you not to wait.”

She wiped her hands on a singed pot holder and craned her neck. “It certainly took him long enough to find you.”

The anemic sister-in-law shifted on her chair. Lewis smiled at her. “’Lo, Sue Ellen.”

“How’re you feeling, Lew?”

“Oh fine and you, Sue Ellen, how are you feeling?”

“Very well, thank you.” Her words hurried. “Where’s Travis?”

“Haven’t seen him since last Thanksgiving at your place.” Lewis’s gaze circled the table top, mismatched place settings dotting it like multi-colored shells at low tide. She really had put out the wedding silver. It glistened in careful rows beneath Superman and Ronald McDonald drinking cups. A gallon of low-fat milk on a braided mat in the center glowed with dew. The rolls looked stale. “Where’s the husband? Out waxing the new car?”

“He’s napping,” Maggie explained. “They drove all day.”

“It’s just like Travis,” Sue Ellen said. “To up and vanish before supper.”

Lewis opened the refrigerator and peered inside. “What’d you do with it?”

“With what, dear?”

Lewis turned on her. “Don’t ‘what dear’ me, Maggie. The beer, where’d you put those two six-packs?”

“Beer isn’t part of the diet.”

“The diet. Beer is not part of the diet.” Lewis slammed the refrigerator door and it shot back open. “I think I’ll decide that.”

“Don’t get worked up, Lew.”

“I’ll work up all I want,” he said. “I’ll work up and drink beer and clog my arteries if I damn well want to.”

“Lewis, please. The company.”

His voice dropped. “My beer, Maggie.”

“I dumped it. And don’t forget what the doctor said about your blood pressure. I dumped every one.”

“I don’t believe you.”

“Down the drain.”

“Maggie — ”

“I did, didn’t I, Sue? Go check the pantry you don’t believe me. The cans are lined up like always, ready to get the deposit.”

Lewis felt fingernails in his palms. “I’m asking you, Mag. I’m asking politely.”

“For God’s sake, look.”

Lewis felt his conviction fold. He touched her shoulder. “All right, then, Maggie. You can’t help yourself. I’ll drive down after supper and buy some.”

“I’ll have to dump those, too.” Her lashes fluttered over brimming tears. “I’ll have to because it’s got to be done.”

Sue Ellen gasped suddenly as if someone had kicked her in the belly. Her bloodless hand shot up toward the threshold where Travis stood supporting himself in the doorway, swaying a little with head hung low. His pale blue oxford button down and the belt edges of the worn corduroys were spotted with dark blood. His nose bled, and his knees were smeared with grass juice.

“What the Christ happened to you?” said Lewis.

Travis moved stiffly to sit at the table. He poured himself a glass of milk, looking disoriented but not ashamed. Sue Ellen rose unsteadily from the chair, coffee sloshing over the sides of the mug she was holding. “Answer him, Travis. Tell your uncle what happened to you.”

He bit into a roll but stopped chewing to press his bloated lip. Travis looked down at the bread, saw it was bloody, and dropped it on the table. “Nothing.”

“Oh, that’s sweet,” shrilled Sue Ellen. “That’s sweet. ‘Nothing,’ he says. Nothing.” Her tone softened, turned sinister. “I’m going to get your father.”

She had reached the doorway when Travis said, “Don’t.” He seemed to mean it. The two young coyotes had found their way to the action and now stood behind their mother in the doorway with identically streaked blonde hairdos, pinching one another.

“I want an explanation,” sobbed Sue Ellen. “I want to know who did this to you. Now, Travis. Get talking.”

“Nothing, Ma. Some kids just started a fight.”

“Just! Just started a fight? Imagine what you’d look like if they finished it — ” She moved toward him but stopped at arm’s length as if she couldn’t bear the thought of touching him, as if convinced he wouldn’t bear up under her trembling shadow.

“I’m fine,” he said. “I’m going to wash up.”

Travis limped out of the room and left the others there to avoid one another in a frozen semicircle. The kitchen seemed hot and bright. The girls communicated under their breath and drifted back to the other room. Lewis heard their incessant music, its beat a chant, pulsing in there, pulsing. He sat down at the table, the blood thick in his face. His own pulse, abrupt and menacing, seemed somehow — for the moment — linked to that music, to those teen dream videos somebody spun out like quick sticky webs with all the same glint in sunlight. What had gone wrong with being young? When had it stopped seeming the best place to be, a place to reach back to and clasp in the fingers like the petals of some rare flower? Youth was a different ball game now, a devil with vacant eyes. The young coyotes could care less if the elder limped in caked with blood. Kids today fed off violence; it consumed and amused them, and this enraged him. Lewis would go in there now and smash that television to bits. “Your brother’s hurt,” he would remind them sternly. “Your flesh and blood strolls in pounded like a piece of veal, and you — ’’ But what would he say? They weren’t his kids. Lewis had no children. He longed for a beer and a bit of quiet, a cigar perhaps, though those, like most things, were forbidden him.

Lewis thought vaguely of his abandoned saltwater tank, of slippery small bodies drifting slowly forward, slowly back. He had the sudden sensation that he and all the others were like those fish, engaged in random motion. He imagined God peering in at them through the glass with whiskey stare, tobacco-stained fingers plucking them one by one over time from the surface and flushing them down a toilet — eternally disappointed, losing interest. Lewis supposed he might retrieve his tank from cobwebs in the basement. He would be more patient now.

Sue Ellen’s voice grated. “Whatever happened to ‘turn the other cheek?’ I raised that child to use his brains, not his fists. You know I did.”

Travis resurfaced looking a little less battered. He’d changed into one of Lewis’s beige polyester dress shirts — without permission — but still wore the corduroys with their stained knees.

“Who was it?” Lewis asked. He could barely contain himself.

Maggie released an undignified snort. “The boy lives three hundred miles away and he’s supposed to recognize them. Ha.”

He leveled his gaze on Travis. “I thought maybe he’d seen them around last visit or something.”

“He was in the ninth grade last time, Lew. Let it be.” Maggie cleared her throat, smiled charitably. She stooped to slice the meatloaf. Sue Ellen probed her reflection in the peeling gold-rimmed china plate, glancing up mournfully at her son from time to time. Lewis crossed to help with the gravy, welcoming the opportunity to peer into the pantry in the event that Maggie was bluffing. She wasn’t. They were lined up in there like petite gravestones, twelve empty Budweiser cans. He settled into his chair with the gravy bowl and smiled uncertainly at his assembled guests.

“Jane, go wake your father,” called Sue Ellen. “Now please, girls. It’s time for supper.” When no reply sounded in the room beyond ancient plaster walls papered with dank marigolds, she turned entreatingly to Lewis. “Could you — ?”

“Sure, honey.” He strained to stand, palms flat on the sticky tablecloth. “Which room’s he in?”

“Yours.” Maggie sat down with a bowl of summer squash and gingerly spread a paper towel in her lap. “It was the quietest.”

“Mine?” Knowing better than to pursue his complaint, Lewis passed through the dim hallway and knocked, pounded, on his own bedroom door. “Hey, Kenny old man, time to chow.” When he got back to the stuffy kitchen, the girls were seated, slurping milk through Twisty-Loop straws Maggie had purchased in their honor from a grocery display sale. Travis seemed to watch his uncle’s every move, and Lewis felt a burning sensation in his cheeks, guilt seeping through cracks in the lower regions of conscience. Travis was, after all, blood. He should have looked out for him. The boy’s gaze remained unusually intense, even after Lewis joined them at the table, and when at last he said something, it was under his breath: “I told you you should have come.”

Lewis cleared his throat and requested potatoes, refusing to be bullied. Sue Ellen had leaned over to spoon squash onto her son’s plate and asked did he have something to say. “Speak up.”

“You’re going to Columbia?” Lewis interjected, staring numbly at the bloated lip. “Huh, kid?”

Travis didn’t so much as nod, knife and fork clicking.

“You don’t answer your uncle, Travis?”

“Yeah.”

“Yeah, what?” coaxed his mother. “Don’t say ‘yeah.’”

“I am, yes.”

Lewis nodded heartily, slapping ketchup on his food. He watched Sue Ellen and Maggie dote on the young ones, brush bangs from their eyes, ease their elbows off the table, turn up the edges of sulking mouths too busy chewing to smile. Lewis tried not to notice the gleam in Maggie’s gaze as she surveyed them. Children were sorrowful, marks of failure, his failure. His body had failed him from the jump, seducing with strength, concealing the clogged tissue and faulty fluids until it was too late to waive his expectations for a family, for longevity. Lewis hated that glazed look of hers and glanced around the table to cultivate his irritation. Irritation suited him, better than guilt.

Maggie’s brother strayed in rubbing his eyes. He was balding and pink-cheeked and bent like an old woman. He didn’t notice Travis, just sat and stared fixedly through a film of sleep as Maggie and Sue Ellen piled his plate with food. After a while his wife said: “For God’s sake, Ken. Aren’t you going to say something?” He stared back at her through a working mouthful of mashed potato and said, “What?”

“What,” mimicked Sue Ellen, turning to enlist Travis, who looked down at his plate. “‘What,’ he says.”

Ken scratched at the pink sleep lines beside his nose and went ahead with his meal, and when at last he glanced at his son, it was only because everyone else was anticipating it. The room was ripe with waiting.

“What happened?”

“A fight,” Travis sighed.

Ken studied a fork full of meatloaf from various angles. “You get a few in?”

“Oh yes, Ken. It looks that way. Doesn’t it.” Sue Ellen left in a huff, her napkin fluttering to the linoleum. Maggie tagged along to comfort her and the two wide-eyed nieces, cheeks hollowed, blew furtive bubbles in their milk.

“Just a friendly inquiry.” Ken’s fork paused in mid-air just before he set it down at a deliberate angle on his plate. He regarded Travis a moment suspiciously, then motioned past him. “Pass the salt if you would. Do something constructive.”

His mouth set in a grim line, the boy got up and crossed the kitchen without speaking. Lewis heard the screen door slam. He waved at a fly and, faced with the hollow sound of coffee cups clinking in saucers, with collapsed pineapple upside-down cake and hours of earnest if passionless debate with Ken about prosports figures or presidential politics, Lewis decided he was better off following Travis’s lead. Despite his weakening knees, he would do well to proceed to the Liquor Mart for beer. Nobody looked at him when he stood up, and out on the lawn he felt drained yet liberated, as if something had been lifted from him. He slammed the door of his truck with a flourish. The pickup bounced and rattled so much that Lewis felt it straight inside to his chest. He drove slowly at first, sure his organs were being systematically creamed in a blender. His insides were turning to mush. Whatever it was holding the whole of him together had to be composed of sheer will. The rest of him, the ribs and spine and spotted skin, was not cooperating. It took effort to resist monitoring — which invariably meant interfering with — his breathing.

His condition brought on a sudden sharp stab of loneliness. When Lewis saw his nephew in the headlights, marching on the side of the road like a soldier to his death, he felt compassion for the boy. He had wronged him. He pulled over and waited with the motor running, breathless and bent on compromise. The road gleamed in his headlights and grass hissed against a sign that read “Railroad Crossing.” He had the sensation, not altogether unpleasant, that he was floating.

“You gonna get in?” he called through the open window, an irrational joy rising in his chest to his mouth. He needed someone to know, to witness this peculiar lightness. “Travis! Get over here.”

The nephew marched past. Stony, intent, eyes on the road. Lewis smiled — here was a challenge — and tapped the gas pedal. He was laughing uncontrollably as he screeched to a stop beside him. An eighteen wheeler thundered past, and its wake sent the boy’s hair fluttering forward.

It shocked him to see that Travis had tears in his eyes. “Hey, kid, come on now, get in here.”

After considering a moment, Travis climbed into the cab without acknowledging his uncle. When the door slapped shut Lewis roared off, craning his neck to peer into his cracked side mirror. Nothing, wonderful not to be pursued, racing on to your purpose till the end. The boy put his sneakered feet up on the dash and remained mute as Lewis pulled into the lot at the Liquor Mart. He rushed inside, ignoring the chirp of young voices that molested him from shadows by the lot’s dumpster, and grabbed two six packs from the glass icebox. He slapped a twenty on the counter, saluted the clerk and raced out again with his change, blood pounding in his ears, the nip of sudden purpose at his heels.

“Here,” he told Travis in the truck. “Drink up. I know it ain’t a Saturday, but you and your old uncle are taking a ride.”

Travis obeyed, not looking any too enthusiastic about it. “Where’re we going?” He gazed forward at the long road. They were twisting past the squat houses and unkempt fields lining the two lanes of Route 20 like children shunning insignificant items in the aisles of a toy store.

“Name it,” said Lewis, swigging his beer. “What’s your pleasure?”

The nephew stared into the hole on his beer can and blinked. “I don’t care.”

“Me neither, kid. That’s the beauty of it.”

Travis looked at him like he might be crazy, and maybe he was. “You get beat up a lot?” he called over the noise of the old engine. “At home, I mean?” It seemed as good a way to start a conversation as any.

Travis dropped his empty beer can peeled another from its plastic loop. “Now and then.”

Lewis liked this boy, had misjudged him. They had some things in common, and Lewis had a purpose, at least for now. He wasn’t going to apologize flat out for what he’d done or left undone, but by the time he was through, Travis would know his intentions were sound.

He raced up beside a yellow Volkswagen packed with children and saw the mother frown as she edged over toward the guard rail to let them pass.

“I’ll tell you something in strictest confidence,” said Lewis, hoping to draw the boy close in complicity. “When I was nine or so I found a body, a dead one.”

Travis took the bait, glancing sideways almost imperceptibly.

“There were these old wine heads lived by the tracks. They slept in weeds and greasy mechanics’ blankets behind the chapel in summertime. They were like phantoms,” Lewis said — because it had seemed that way when he was a child; he saw them always out of the corner of one eye, a blur of covert speed rattling brambles.

“I was in a warehouse alley near my house that morning looking for crates on account of the Depression was still on and my mother thought we had to move closer to the city. It hadn’t been there long,” he said. “The body. I was in that same spot the day before.”

He told how he bent down to have a look — had never seen anybody dead before — when a shadow passed abruptly on the sooty brick behind him. He’d felt a sudden, sharp pain in his neck, then blow after blow as a boot kicked him until he couldn’t see straight for the pain. At first he thought it was a monster, Lewis said, relieved that Travis had straightened up in his seat to listen.

He had watched his persecutor descend and retreat that day in a shaggy mass, squealing with broken teeth. “But once it stopped hitting me, and my eyes focused I saw more clearly,” he said. “And guess. You guess who it was.”

Travis pinched the side of his can so the aluminum wrinkled, made snapping sounds. “Who?”

“It was a woman. A goddamn skinny woman. His girlfriend or something and she was miffed, crying because I’d touched it.”

“What’d you do?”

“I ran, what else? Ran like hell.”

The boy held his beer in one hand and used the other to fiddle absently with his fat lip. Lewis watched and after a moment smiled fondly at the memory. “A damn skinny woman. Beat me within an inch of my life.”

Travis looked panicked. “Uncle Lew?” he asked. “Aunt Margaret said —”

Lewis snatched the can of beer from between his legs and drank from it. “What’s your game, Travis? I take you out to forget about all that, women fussing and such, and this is my reward?”

“Sorry.”

Lewis wedged his beer back in place. “How many were there?”

“What?”

“How many kids beat up on you?”

“Five, maybe six.”

“Goddamn pansies, can’t even manage a fair fight.”

“It was my fault.”

“Come on, how could it be your fault?”

They were held up behind a crawling yellow taxicab that seemed strangely out of place in this landscape. Lewis tapped the horn, his voice excited and deep. “Come on nickel pusher, hustle.” In a moment the highway blossomed, two lanes became four, and Lewis watched the taxi’s headlights recede in his mirror. The last of the year’s wild flowers — purple, yellow, the occasional swath of white — swayed gently beside the dark granite walls.

Travis steadied his own voice as if to dull its insistence. “It was. It was my fault.”

“How d’you figure?”

“I was nervous when they came up beside me. People can tell that. And I smiled. I shouldn’t have smiled.”

“You shouldn’t have smiled?” Lewis licked his dry lips and stared forward at the road. “If that’s not the damnedest thing I ever heard.”

But even as he spoke, even as the mother in the Volkswagen appeared out of nowhere and passed them on the left — her kids bobbing in the back seat, three raucous boys in Sox caps, steaming up the windows — Lewis supposed his nephew was right. He shouldn’t have smiled. For the sake of simplicity he should have looked away, kept going. But it was too late for that now. “What say we check out the batting cages in Fiskdale? I’ll bet you’ve got an okay swing for a bookworm.”

“Yeah, well. Better than my left hook.”

Lewis laughed soundlessly and floored the gas pedal, feeling the vibration somewhere deep inside his chest.