This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 4, "Drive-Through South." Find more from that issue here.

Early spring days in southern West Virginia are chilly, the smell of coal smoke lingering in the air. Roads rut out into mud tracks, and yards turn swampy, but the afternoons are warm, and the faint haze of green on the sides of the mountains holds out the promise of new growth, burgeoning gardens, and the warmth of summer.

It was on such an afternoon in 1987 that Beth Spence drove through a creek outside of Harts, West Virginia, to visit Leo Watts.

A native of West Virginia, Spence began looking at rural homelessness during her time at Covenant House, an urban shelter in the state. Working with a Catholic sister, Spence interviewed families in the Harts area to assess the housing needs of “the hidden, forgotten homeless who live up the hollers and along the ridge tops. I sat down at the tables and talked with the women, usually,” Spence remembers. “It was easy to talk about housing problems, but then we’d move into health. Most of the children had health problems, including childhood pneumonia. The children who were having so many health problems were also failing in school.”

Leo Watts was friendly on that spring day. He came out onto his porch to talk to Spence. His arms were bandaged up to the elbows — the result of fighting a fire that could have burned his house down.

Watts’ house had large holes in the walls and ceilings, dirt floors in the bedrooms, and no running water. It was not atypical for an area where it’s estimated as many as 50 percent of the families live in substandard houses.

“I built it, but it’s pretty bad,” Watts told Spence. “It’s a roof over my head, but it leaks. It’s about like being outside. It ain’t much, but it’s all I got.”

Once Spence had completed an initial assessment in Harts — many of the homes she visited, like Watts’, didn’t meet the United Nations definition of a house — she and the Catholic sister arranged a community meeting.

“It was amazing,” Spence remembers. “About 50 people showed up. We said, ‘Look, we don’t have a program, and we don’t have any money, but we’d like to get something started.’ Thirteen people volunteered to be on the steering committee, and seven stuck with it.”

Nora Kelley, a welfare mother with four children, was elected the first director of the new organization. When a Presbyterian church group donated $50,000, Harts Community Development had a system in place to use the money to build houses. “The men had sort of been in the background,” Spence remembers. “But when the money came through, these nine guys — all on welfare or disabled — went out and walked the property. That’s something Habitat for Humanity might not have thought of — walking the property and then designing a long, skinny house specifically to fit this piece of land.”

A crew of nine built the organization’s first house — a house for the Watts family, which Leo and his wife Marlene helped design and build. The site supervisor found young, unemployed men to work; after taking them through the construction of the house, Harts paid for them to take their licensing exams. A crew of women came in the evenings to hang drywall and paint.

Since its inception in 1989, Harts Community Development has built seven houses and rehabilitated several more. “People were convinced to really look at what they needed to do for their community and how it could be done rather than following the money path,” Spence says.

“The most important value that undergirds the work is the belief that poor people must be allowed to make the decisions, all the decisions — even the bad decisions — and make mistakes and learn from them, and go on from there,” Spence continues. “There’s got to be room to allow that to happen because if you don’t have that, you don’t have empowerment. This empowerment thing, to me, is more important than houses.”

Got to Be People

Clean, safe, and affordable housing, entrepreneurship and job creation, and accessible quality health care are all indicators of a thriving community. During the War on Poverty in the 1960s, the federal government funded community development programs providing necessities to poor communities and hard-pressed neighborhoods. A lot of what’s now called community development revolves around housing projects in inner cities initiated by “community development corporations.” Public and private money is earmarked for physical development — but the balance sheet is the important part.

The people in the ventures have little input. As a result, many of these projects fail to bring about any real change in the communities they profess to help.

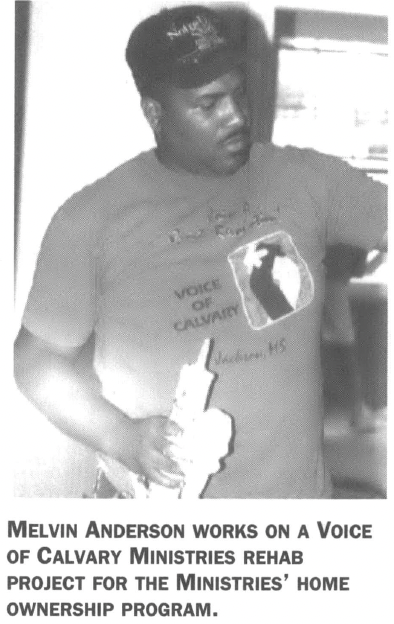

“When I became involved in the movement, community development was a process to involve people so that their capacity could be built up,” says C.J. Jones, development director for Voice of Calvary Ministries in Jackson, Mississippi. “Poor people got into community development because nobody else cared. People still don’t care about the poor. But they do care about physical development.”

Grassroots development, on the other hand, seeks to expand capacity and resources of whole communities, working from the bottom up. The emphasis, according to Ralph Paige, director of the Federation for Southern Cooperatives, is “not necessarily looking at the bottom line, but looking at the things people need, the ability for a community to control its own destiny.”

Ben Poage, a minister with the Kentucky Appalachian Ministry, has worked for such change for over 20 years. The communities he finds himself in are often struggling with legacies of the golden age of mining on the Cumberland Plateau. Now that the big companies have pulled out, many towns are left “caught up in a seemingly endless downward spiral of poverty,” writes Poage.

Like Spence, Poage stresses the importance of developing the resources already existing in the community — the people. “The economic salvation for Heartland Appalachia is not through enticing outsiders to come in and set up factories, but is found in our own ability to use our human and natural resources, with some outside capital and technical assistance, to launch community-owned and community-run enterprises.”

Grassroots development gives people the opportunity to create employment and provide an extraordinarily diverse number of services, based on the needs of their own community. More and more groups provide development funds, micro-enterprise loans, entrepreneurial training, and co-ops for craft makers and rural minority farmers. Motivated by the conviction that the only sustainable development is for, by, and of the community, leadership development programs, housing construction and rehabilitation, health clinics and education centers have also been created.

For Phyllis Miller, director of the Mountain Women’s Exchange in Jellico, Tennessee, there’s little choice. “Economic development in the mountains must come from within. The geography just does not lend itself to attracting industry. We must help ourselves and each other if we are to survive.”

Building the capacity of people, say practitioners of grassroots development, is the only way to ensure their efforts’ inclusiveness, and ultimately, the ability to bring about significant change. “Any time I think about economic development or community development, before economics there’s got to be people,” says Margarita Romo, founder and director of Farmworker’s Self Help in Dade City, Florida. “There’s got to be strong people. There’s got to be nurtured people. There’s got to be people that first can begin to see the worth in themselves.”

Converting Power

Many of those who practice the grassroots version of community development, including C.J. Jones and Ralph Paige, came out of the civil rights movement. The roots of community-based economic development reach back even further, to Tuskegee Institute, to church-based support groups in the mountains, and to the cooperative movement of the late 1920s. People involved in the civil rights movement turned to that legacy of community-based economic development as the most appropriate vehicle to continue working for social and economic justice.

The Federation of Southern Cooperatives headed by Paige was founded in 1968 in order to provide minority farmers in the rural South with some power in the marketplace. Voice of Calvary was founded in 1962. For Paige and Jones, working for economic change at a grassroots level was a natural extension of their struggle to vote, to be represented, to have a voice. It became a matter of converting political power to economic power.

Jones remembers a time, during the early days of the civil rights movement, when a group of families was evicted from the plantation they lived on because they voted. Someone donated a field, and the families lived in tents. Jones says it was this incident which spurred him to become involved in community development. “We didn’t own land. We didn’t own any jobs we could send these folk to. What you had were these folk who were completely and totally excluded from the economic system. I began to feel that the issue of justice in America was an economic issue, not a social issue. A lot of the social issues came about because of the economic injustices.”

In many ways, community-based economic development was a practical response to a system which is exclusionary. “Grassroots involvement is an essential part of the delivery of goods and services,” says Ed Bergman, professor of economic development at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. “It’s the way people get what they need, what the system doesn’t provide.”

By the mid-1970s, the roots of the community-based economic development movement were growing deeper and spreading wider. Money from the Office of Economic Opportunity spurred a number of community development efforts. The Special Impact Amendment of 1968 established the first community development corporations, and those grew in number and capability. The Ford Foundation came on the scene to provide financial support and technical assistance, allowing the development corporations to do housing work across the country.

The money didn’t always trickle down all the way to the grassroots, though. With the money from the government and foundations came their agendas. The funders wanted to see tangible results, especially housing. Farmworker’s Self Help, providing education, health care, and job opportunities to migrant workers, didn’t fit into the agendas. The organization survived for 14 years with no federal funding. C.J. Jones says the money was accessible to projects on which he worked, but its uses were so restricted it was of little help.

Obstacles to these groups’ work still exist. Mary Tyler, co-founder of the East Jackson Economic Development Commission and executive director of Area Relief Ministries, points out “the general image that our population has of poor and minority people. They automatically assume that you just don’t have what it takes to sit at the table with bankers, and with corporate people, to discuss intelligently their putting some of our resources back in our community. They tend to want to talk with everyone but the people at the bottom. And that’s who they’re going to have to talk to.”

Despite the many impediments practitioners of community-based economic development face, those involved in the work say the successes are worth the effort. “I work with a lot of women, heads of households,” says Ralph Paige, “and it’s a wonderful thing to see them come out and say, ‘Hey, I ain’t gonna take this any more. I am a human being, and I can do.’”

Tags

A. Lorraine Strauss

Lorraine Strauss edits Threshold, the magazine of the Student Environmental Action Coalition and was a summer intern at the Institute for Southern Studies. (1994)