This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

All around metropolitan Atlanta, there are signs of a cultural change. There are Hispanic grocery stores, Asian nightclubs, and a Spanish newspaper. There are teachers who know how to educate a child who has never spoken English, and police officers know who to call when they pick up a Cambodian refugee who is confused and unaware of his rights.

Amid the ethnic diversity, living at the end of a quiet cul-de-sac in a suburban Atlanta subdivision, there is Yung Krall, the daughter of a Vietnamese Communist revolutionary father and a pro-democracy mother.

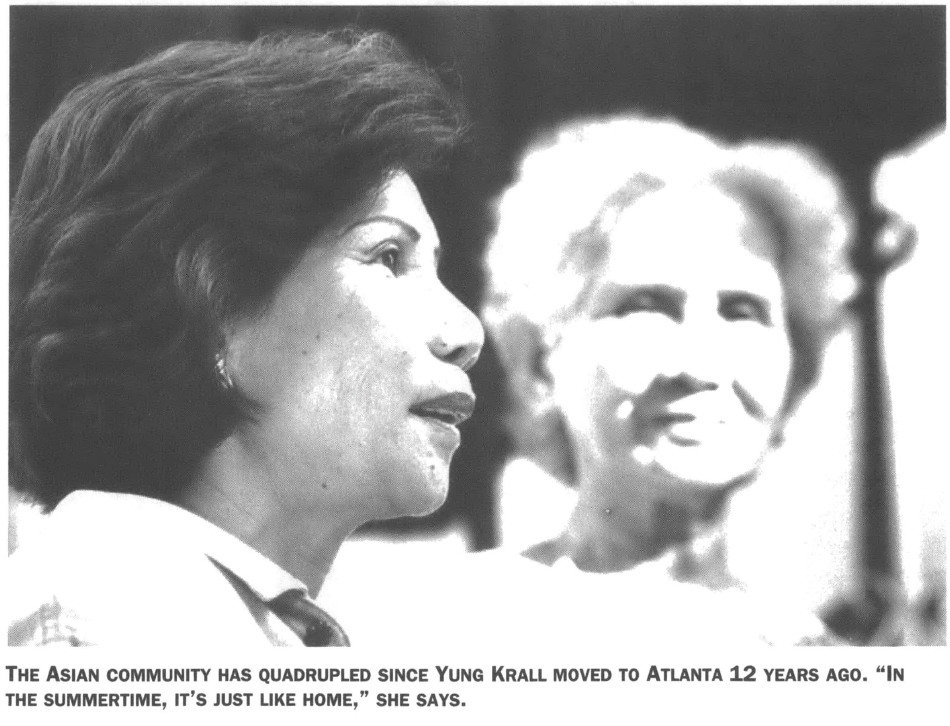

When she came to Atlanta 12 years ago, Krall’s accent and her story would have dropped some jaws. Today, she is not such an oddity. The Asian community has quadrupled over the past decade, making the city home to one of the fastest-growing Asian populations in the nation.

Krall herself has welcomed thousands of these newcomers in her job with the county health department, where she helps refugees from across the world get medical care when they are sick, and helps doctors understand the foreigners they are treating.

“People like Atlanta,” she says. “They move here because of the positive news by word of mouth. People say Atlanta is a good place to live. There’s a lot of jobs here and the weather is nice. In the summertime, it’s just like home.”

Krall’s journey from the jungles of South Vietnam to the suburbs of the American South has been a 25-year trip. It has left her thoroughly Americanized in many ways, but still clinging to her native land and identity in many others.

“I miss Vietnam every day, I think because of my work,” she says. “I am with the refugees every day.”

At home she keeps a glass jar filled with soil — half from North Vietnam and half from South Vietnam. To look at it brings back the memories of a life filled with conflicting loyalties.

Her father moved to North Vietnam when Krall was nine to join the fight against the French, leaving the rest of the family behind in the South. Her mother supported the family, and while her father rose in the Communist Party ranks, the rest of the family came to reject Communism.

In 1967, she met John Krall, a young American Navy pilot in Vietnam for the war. They fell in love, and he wanted to get married. She wasn’t sure whether he’d want to marry the daughter of his enemy.

“I said, ‘I’m the daughter of a Communist.’ He said, ‘So?’”

So she left her country, moved to California, and married John in 1968. During the next decade, she raised their son as they traveled the country, living near naval posts from Washington, D.C. to Hawaii.

When it was time for John to retire, Krall wanted to move to Atlanta to be near her sisters and her mother, who had left Vietnam in 1975 shortly before the fall. “I was so lonely for a big family,” says Krall, who is now 48. “We always had an extended family in Vietnam and again I made an extended family here.”

While she has seen her family and hundreds of others from all over the world create new homes in Atlanta, Krall believes this Southern metropolis still does not live up to its billing as an “international city.”

“Atlanta invests a lot of money in making itself an international city, but they don’t invest their emotions into making it an international city,” Krall says. “An international city enjoys other cultures, it’s curious about other cultures and respects other cultures. It’s proud of other cultures and people there know about other cultures. And they don’t get stuck with black and white.”

Like the rest of the South, Atlanta is obsessed with the issue of race, especially when it comes to politics. But the frame of reference has not yet expanded to include the new minorities, so complex are the continuing problems between Atlantans of African and European descent.

The state has not made it easy for foreigners with limited language skills to get licenses for driving or for jobs that require certification. And unlike residents of a truly international city, many people in Atlanta are still uncomfortable with language and cultural barriers.

It may take more time, more people, more than simply winning the 1996 Olympics to change all this, Krall says. The Asian and Hispanic communities in Atlanta are among the fastest-growing in the nation, but they still are a tiny minority — less than five percent — of the total population, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

“There are not enough of us, not enough of the international population,” Krall says.

Still, Krall is happy here. She has her family. She has an important job and contacts with refugees that help her keep her ties with the other South she has called home.

“It’s like having two parents, two good parents,” she says of her solid ties to Vietnam and to the United States. “Because of circumstances, I stay here. And it’s great that I stay here. But if the Communists never took over, I’m sure that we might be in Vietnam.”