Undisclosed Location

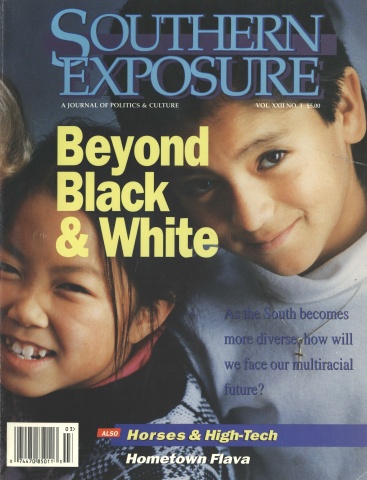

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

I said yes to Borden’s proposition because I was vulnerable; I’d just been turned down for a job at the local rodeo as one of the girls in shorts and boots who get the crowd excited by pretending to rescue the clowns from the bull. I was after some color and action, anything but typing, and I already owned a pair of quality boots, but this was an insider’s job — you had to know a cowboy, or at least a clown. Plenty of girls had hand-tooled, snake-trimmed boots like mine, or so the smirking rodeo administrator said. He seemed not to like my looks. So, back home, when fat Borden hissed at me from his doorway, his big gleaming face and shirtfront filling the crack between door and jam, I stopped. Usually I tried to cat-foot across his landing, a tough trick on our building’s old hollow hardwood stairs, but this time I was already resigned, and still wearing my fancy, clunky boots from the rodeo interview.

“Hey, CeCe, stop a minute,” he said. “Where you been? Those are nice boots you got, none of that endangered shit, right? Listen, I got something you ain’t gonna believe.” He always said this, and it could mean anything: macaroons, a ceiling leak, new mollies in his tank, Kristy McNichol all grown up on TV. He worked late nights watching over the parking lot of a small-time chemical plant, and spent his days, as far as I could tell, sauntering heavily around his apartment, turning his appliances off and on, and looking out the window. When I came up the block he would often appear there, wave, and then let the curtain fall briskly, as though he had to get back to some top secret business or lingerie model in his bed. Of course I knew that wasn’t the case — his girlfriend showed up sometimes in the afternoons, and she was faded-looking, bottom-heavy. She wore a droopy uniform tied with an orange sash, and her name, Frieda, in orange italics across the breast pocket, and though I recognized this as some fast-food get-up, I hoped vaguely for his sake that she was something more like a crossing-guard — kind, maternal, respectable.

“What can I do for you, Borden?” I said. The canned spaghetti smell of his apartment drifted out and surrounded us, filling the hall.

“Well, as a matter of fact, I noticed you been around a lot lately, and I thought maybe you were between jobs.”

“Actually, this is my paid vacation,” I told him. It was true. I’d set an office record by holding the position of typist for three years, so they’d given me this—nothing sparkly or engraved, just a week. Borden didn’t have to know how I was spending it, looking for work in rodeos and water parks and petting zoos.

“Well, more power to you,” he said. “God bless. You enjoy yourself, okay?” He ran a crumpled, cornucopia-patterned paper towel over his brow. I could have gotten away then, but for some reason I asked him what he had wanted.

He flushed, lit up. “I need a housesitter,” he said. “Starting Monday, for a month. Maybe your cute friend with the Mantra? She sure is a sweet thing.” He meant my best friend Jeannie, who was pointy and petite and drove an Opel Manta.

“She’s full-time at the bank now, and she’s busy planning her wedding,” I said. “So she’s not available. So what’s up, Borden? Everything okay? Where are you going?” In two years I doubted he’d ever spent more than twelve hours at a stretch away from his place.

“Undisclosed location,” he said. He glowed strangely; drugs occurred to me.

“What are you talking about?” I said. “Are you sick?”

“No, just trust me,” he said. “Why do you always look so suspicious? Jeez, you’re like what’s her name, Murder She Wrote. Listen, you just gotta keep up the aquarium. I’ll give you seven bucks a week, that’s a buck a day. You don’t have to stay here or nothing. I know you got a busy life. You can bring your cute friend over if you want, though.”

I pictured Jeannie’s evil grin, her small hands rifling through his personal belongings. She referred to him as Elsie. “Okay, Borden,” I said. “Show me what you want me to do.”

“I gotta show you later,” he said. “I got a meeting.” He stepped out and shut and locked his door. I stood there on the landing watching his fat back, his baggy hips retreating down the stairs. FBI, I thought. America’s Most Wanted. Something Anonymous. Betty Ford.

The next morning, there he was, unbelievable, in the paper, holding a giant reproduction of a check from Florida Lotto like a clown’s prop: $2.4 million. His happy, grainy face was the size of my thumb. Thomas Borden, read the caption, thirty-two, and I was shocked; I’d thought that Borden was his only name — like Dopey or Dumbo — and also that he was years and years older than me. There was no story, only the paragraph-long caption, which noted that this particular win was especially poignant and thrilling because of the death of Borden’s parents in a house fire four years previous. Things were finally taking a turn for the better for Borden. He was quoted: “My advice to everyone playing Lotto, don’t give up. You never know when the ball will start to roll in your direction.” His grin looked knowing and wholesome, instead of fat and sad. “Seven bucks a week,” I said out loud. I thought of my mother, who’d recently had to have a marble-sized lump removed, and then there was a distant cousin of mine whose baby got a fever and could now no longer speak: I deserved to win. But those items weren’t bad enough to go in a caption, and neither were the real items of my life: my stuck-up sailor boyfriend getting sick of me, for instance, saying he had to “move on” because I “lacked serious ambition,” when I’d only started dating him as a joke, a game, something to tell Jeannie — sailor seeming as believable a profession to me as pirate or lion tamer or Indian chief. Or the rodeo man, a stranger, deciding I was too ugly to save clowns. Or Jeannie, the wild one of us, shopping for rings with her professor. Looking at Borden’s smudgy 2-D face, I felt panic, realizing that if he won, no one else I knew could ever win; Borden, only Borden, was the one among us who deserved to win.

I could hear his phone ringing as soon as I stepped into the hallway, and when I got down there it was impossible to talk to him. He opened the door for me but ran back to the kitchen, where he was trying to rig up an answering machine which the ringing phone kept fouling. The machine was a cheap model, I noticed, the same brand as my blow dryer. For a moment I actually pitied Borden, “Big congratulations,” I said.

“Yeah, thanks,” he said. Drops of sweat fell from his brow onto the blinking, clicking machine. “You’re not gonna have to worry about this, once I get it hooked up.”

“That was a pretty smart idea,” I told him. “Leaving town.”

“You bet,” he said. “The Lotto Commission advised it. To avoid unwanted solicitations and attention. From acquaintances, you know.”

“Are you taking Frieda?” I asked. She was the only person I ever saw going in and out of his place, and I imagined she would look healthier with a nice tan to set off her hair. I wished that for her, honestly.

“Even that I can’t say,” Borden said. “But I sure wouldn’t mind taking your friend. Listen, you mind if I just give you the key and show you the brine shrimp? I’m kind of busy. I think I’m gonna leave tonight. I really appreciate this, CeCe.”

“Oh, no problem, I’m just so happy for you,” I said.

“Okay,” he said. “Now, you ever hear the expression ‘ Your eyes are bigger than your stomach’? ’Cause what you gotta remember here is that the fishes’ stomachs are small, you know what I’m saying? If you look at their eyeballs, you’ll see what I’m saying.” He held his hand up to my face and showed me his finger and thumb pressed together, as though he were holding a tiny, invisible bead. Together we looked significantly at the invisible bead. Seconds went by, and finally he shook his head. “Jeez,” he said, “you just never know when the ball’s gonna roll your way.”

Well, the fat’s in the fire now!” Jeannie shouted, when I told her. Her voice was spotty with static because she was on the cellular phone the professor had given her, on her way to lunch at some Pavilion place. She always called from her car, even though the phone on her desk at the bank was unmonitored and had a hundred special features and worked fine, and she always shouted the whole time and complained about the bad traffic she was stuck in. We’d known each other too long for her to be showing off, but that’s what it was — like complaining that she looked too young and was always getting carded. She wanted me to say, again, how special the professor was, how lavish, but I refused. He was petite like her, always looked like he’d had his haircut that same day, and spoke to me in a measured, modest little voice, as though my big bones offended him, as though my neurons and dendrites were large and ungainly and an embarrassment to neuroscience, his honorable chosen field. Delicate, well-groomed men often treated me this way, as though I were likely to breathe up all their air or just fall on them like a tree, but when Roger did it I had to pretend not to notice — we were supposed to become great barbecue buddies, in-laws, practically. And yet even gleeful Jeannie toned herself down around him, I’d observed. He couldn’t possibly appreciate the real Jeannie, the Jeannie I’d known all my life.

Now, on the car phone, she was her regular self, shouting that I should have drunk the Riunite. She meant the night I’d moved into my apartment, when Borden had opened his door eight or nine times during my trips up and down the stairs, not offering to help but pretending to check different things: the mail, his deadbolt, a bulb that hung over the landing. After a half-hour of this he finally affected to notice me, and brought out the bottle. “You look like you deserve a glass of this,” he said. I shook his damp hand and told him I was allergic to sulfites. “Oh, yeah,” he said, “I saw that on Sixty Minutes.”

“You’d be having millionaire babies now, boy!” Jeannie yelled.

“Okay, okay,” I said, and invited her over later to hang out at his place, to sit in the apartment of a millionaire.

“I’ll break my hip in his bathroom and sue!” she shouted.

“But don’t invite anybody else this time, okay?” I said. “We don’t want things to get out of hand. Reporters might be lurking around, or other, more dangerous people.”

“Alone’s better, actually,” she yelled, “because I need to talk to you some more about my wedding.” She hung up, and the rush of her traffic was cut off with a click. My living room swelled with quiet. I remembered I needed to launder my lace-collar dress to wear to work, where they planned to take my picture for the newsletter, for having earned this bonus. Only Saturday and Sunday were left of my vacation. If I shut my eyes I could see the days, like empty boxes, lined up in front of me.

We had all of Borden’s bug-flecked lights turned on, a bottle of his bargain gin opened in the kitchen, and we’d switched off the ringer on the phone; the little answering machine was clicking away on a corner table like The Little Engine That Could, silently recording messages. A pizza was supposedly on the way, though we’d had to fight with the man on the phone, who said he’d taken half a dozen orders for this address already. “A hundred pizzas,” he said. “A pizza with dollar bills on it. A Beluga pizza. Jesus, you think I’m an idiot?”

“Look, we only want one,” I finally said. “We’re using a coupon.” That had worked.

Jeannie was twirling shoeless across the rug, her lacy slip flashing white, and I remembered meeting her for the first time in fourth grade, her wearing slips under her plain school dresses even then, as though she were better than the rest of us. “I’m spiking these guppies,” she said, waving her drink over the tank.

“Check out their eyeballs first,” I said. I was slumped on Borden’s low yellow sofa, my cheek pressed against the worn velour, which smelled, up close, not like spaghetti but like a stuffed terrycloth pony I’d carried around everywhere until I was eight or nine years old. I had sucked on its matte yarn tail whenever I needed it, and when foam pieces starting leaking from the rump, my mother cut the tail off for me to keep and threw the body in the trash. I took gulps of Borden’s cheap gin, recalling how I had imagined the pony’s body being absorbed by the roots of a nice tree somewhere, being soaked up and incorporated into the trunk of the tree, the nicest thing I could imagine happening to trash.

“Liven up, will you?” Jeannie said.

“I’m just wondering what stupid Borden is going to do with all that money,” I said.

“Well, let’s listen to that answering machine. Can’t we just turn up the volume, without messing things up?”

“You better do it,” I said. “You know how to use a car phone. You know how to use a safe deposit box. I can’t even get a job at the rodeo.”

Jeannie gave me a look and adjusted the machine, which was in the middle of taping a message. “Mack Fine,” a man’s voice said. “Fine, Breen, and Janky, financial consultants. Flexibility is really what we’re all about, so don’t feel limited, say, by the list of services you see in our flyer.” The doorbell buzzed.

“It’s Janky!” Jeannie screamed.

I let in the flat-haired delivery-girl, who was holding the pizza box propped against her hip like an empty cocktail tray. “Large mushroom onion,” she said. “Ain’t you the lottery girls?”

“We is,” Jeannie said, “but you ain’t gettin’ no big tip.”

“We flipped coins over who got to deliver this one,” the pizza girl said. “They at least want the lowdown on you two. You know the guy who won, right?”

“I do,” I said.

“I does,” Jeannie said.

The pizza girl shook her head, and her stringy hair swung slowly. “What I wouldn’t give,” she said. “What’s he like? Is he your old man?”

“Oh, well,” I said, feeling my gin a little, in the way I kept nodding my head to the rhythm of her swinging hair. “He’s a big guy, a stay-at-home kind of guy . . .”

“. . . Dr. Stopes, I don’t know if you remember me,” came a sudden nasal voice from the answering machine. The three of us stood still and listened. “The Dermatology Lab in St. Paul. You were here last March? How are your nevi doing, have you had any recurrences? Anyway, all of us here just wanted to say, you know, congratulations.” A high female voice yelped in the background. “Patty, who takes your appointments? Says congratulations. Anyway, we have some new samples of that fluoroplex generic we can send your way, so if you’re interested, you can give us a call at your convenience. Congratulations again.” The machine clicked off and reset itself.

“Man, doctor wants to do you a favor,” said the pizza girl.

“Why are you even still standing here?” Jeannie said to her.

“That was compassionate,” I said to Jeannie after we’d let the girl out. I was back on the smelly couch, picking the oily onions, her idea, off my slice.

“Me?” she said. “What’s wrong with you, anyway? You’re probably turning into Mrs. Borden sitting on that couch.”

“And I’m also sick of looking at that Victoria’s Secret shit, by the way,” I said. “Am I supposed to be aroused or something?”

She came over and stood in front of me and raised her skirt, holding the hem by two fingers so that her slip hung there in my face. I felt like I was watching a blank projection screen, waiting for a movie to start. I remembered a fight we’d had in fourth or fifth grade in which I had called her “prostitute” and she had refused to reply, to that or to any of my insults, except to say, “Good.” That had been our last real fight, now that I thought of it. “Is this how you’re going to behave at your big important wedding?” I said.

“You’re not really joking, are you?” she said. She looked at me and let her skirt fall. “Well,” she said after awhile, “and I don’t even feel bad telling you this, anymore, the way you’re acting, but you’re no longer maid of honor. Roger’s sister is back in the country.” Roger’s sister didn’t like Jeannie and had once given her a bad haircut on purpose.

“You could have just told me that on your cellular,” I said. “In fact, you could tell your whole life story on your cellular.” In a flash, I saw Jeannie and me on the school playground in our green Girl Scout uniforms, forming the letters of the alphabet with our small, slender bodies, acting out for our own amusement the physical progression from A to B to C, cocking our knees and elbows at bizarre angles, getting tangled in our sashes and laughing so hard at one another that we couldn’t speak. For the first time, I saw that I had always operated on the unconscious assumption that our slow, steady movement away from childhood was arbitrary, that like an amusement park ride time would eventually pause, or halt, or even reverse itself and take us back in the other direction.

I heard the fierce scrape of Jeannie striking a match in the kitchen. “You can’t smoke in here!” I yelled. I had to take practically a whole breath to say each word, as though something large, an invisible Borden, had settled down on me; it was hard to hold things in my mind. A woman’s voice on the answering machine was saying something about never forgiving, and I thought: “security.” Then I realized I had them reversed; the phone woman was talking about securities. “Never forgiving” had come from me. A knock that seemed to have been going on for some time got louder, and I got up to answer the door, but no one was there. The pounding came again, from somewhere over our heads, definitely inside the building. “Jeannie, get out here,” I said. “Someone’s doing something. Something’s happening.”

“It almost sounds like it’s coming from your place, doesn’t it?” she said. She came through, not fierce at all but oddly languid, blowing smoke at the aquarium. The knocks stopped. “I’ll go up there and check,” she said.

“Don’t leave me here alone,” I said. “I’m serious.”

“Here, give me your key,” she said, talking as one would to a child.

I locked the door behind her and went to wait by the window, craning my neck to see if someone who wanted to kill us was pressed up against the building, but all I saw was the empty, darkening view down the street. Two old men were attempting to wheel themselves out of the nursing home at the end of the block, ignored by a group of nurses laughing and smoking cigarettes under the security light. I saw this all the time, had called to complain about it, and I wondered if Borden ever watched it; through this window he had the exact same view I did. The glass was greaseless, spotless. I imagined what our two faces must look like from the outside, one on top of the other, peering through our windows with the blank, identical expressions of passengers on a train. The other units in the four-plex faced north, looked out over a frontage road that led to a mall, though the tenants on that side of the building changed frequently and weren’t around much while they did live there: young couples getting through the winter before they got married, attractive divorcees getting back on their feet, graduate students finishing up their dissertations. I never noticed any of them looking out their windows.

I waited, watching the nursing home and listening to Borden’s messages; four more financial advisors called, and then a woman who had to be Frieda came on, though her voice was more formal and youthful than I had imagined. “I never know what to say on these machines,” she said. “I hope you’re having a lovely time, you deserve it, Tom. Well, I thought it would be nice for you to have a message when you get home. I’ll sign off now. Have a lovely vacation.” The click and silence after her call filled me with sadness: poor Frieda had been left behind, the way we were all going to be left behind, only in her case it was worse because she probably loved Borden, in her own drab, faded way. Goddamn Jeannie, I thought, as though she had something to do with it.

Upstairs, the energy of real fear surprised me. My apartment’s door was unlocked and I let myself in, trying to comprehend that something terrible, life-changing, could be waiting, just moments ahead of me in time. I stalled there by the door, switching my three-way lamp twice through bright, brighter, brightest, and then Jeannie padded in, blinking and nude, her skinny body, tiny breasts exactly the same as they’d been in sixth grade. For a second I thought rape, hostage, help, but then I saw her expression and something deflated in my chest. “Bachelor party hijinx,” she said.

“Hey!” the professor called from my bedroom, in his proper, brain-lecture voice. “Is that CeCe? CeCe, come in here! CeCe, I want to say hello!”

“You were in my bed,” I said.

“This wasn’t my idea, honest,” Jeannie said. “I didn’t even know it was him until I got up here.”

“CeCe! CeCe!” Roger called. He said my name like it was hypothetical, a joke.

Jeannie stepped up and tried to hug me. “Just ignore him,” she said. “They were drinking Rumpelmints. He thought we were at your place. He tried to beep me but my battery was dead.” I tried to push her away, but she got her skinny arms over my shoulders, her chin against my ear. “It’s okay,” she said, her oniony mouth warm against my cheek. “Nothing is going to change, we’ll see each other all the time, nothing will be any different.”

“Jesus, you have a beeper?” I said. I couldn’t get her arms unlocked from around me.

“CeCe!” Roger shouted. “Let me see those boots of yours! I wish Jeannie would get some of those!”

“Don’t worry, don’t worry,” Jeannie was whispering, only it was no longer Jeannie, and no longer me. I shut my eyes and put my hands on her bare back, hypothetically, feeling her ribs, her smooth sides and small breasts, her onion breath in my hair, and I thought, This is what Roger does, this is what he gets, and I tried to imagine what kind of luck he thought he had, getting this. It no longer had anything to do with me. Then I imagined Borden imagining this, sitting by the window wanting this, at the expense of poor, polite Frieda. And who could blame him? Everyone wanted it. I pushed Jeannie hard and she stepped back.

“What,” she said. “What is your problem? Is it the lottery? Any of us could have won the lottery.”

“Do whatever you want,” I said. “I’m going back down to Borden’s.” Prostitute. She followed me out into the hall and stood there naked, blabbing away like an anchorwoman.

“CeCe, nothing substantial has changed since yesterday, or the day before that, or the day before that,” she was saying. “You are creating a self-fulfilling prophecy!” “Fine, good,” I heard her say, when she thought I was finally out of her range.

In a dream the sailor came back to me. We sat side by side on a dock overlooking some calm water, and he helped me put back together the pieces of a paper horse I had accidentally torn up. The pieces of the horse were small and he took them into his hands with great tenderness. I turned to look at him, filled with feeling, and the gold buttons on his uniform caught the sun, blinding me. Through the explosion of light I reached for him, unable to see my own fingers, and then the spaghetti smell was there, as close as my own mouth. It was Borden, his face right there, the lamp switched on behind him, and I pushed back at him frantically. “Hey, pussycat, pussycat, take it easy,” he said. He was sitting against my hip, pressing me into the back of his sofa, grinning down at me with gray teeth. Chest hair bloomed in a small bouquet from under the neckline of his t-shirt. “Don’t touch me,” I managed to say.

“Hey, okay,” he said, raising his hands as though I’d pointed a gun at him. He stood and shuffled off toward the kitchen, his thighs whiffing against each other. “Jeez, I live here,” he said.

“What are you doing here?” I said. It was late, three or four, and Borden’s living room seemed calm, even peaceful, the mollies moving slowly up and down in their tank. I pulled myself into a sitting position and looked around for my boots.

“Well, it’s funny,” he said. “I had a funny feeling. I got all the way over to Epcot, got in my room, got one of them mini-refrigerators with one of everything and then some other stuff you get free, fruit and that, and then I go take a look out the window and that big goddamn ball is sitting there. It don’t do nothing, you know? It don’t rotate, don’t open up, don’t take off, nothing. Gave me a bad feeling, just knowing it was out there. And then my legs was acting up, you ever hear of restless legs syndrome? Secretaries get it, from all that sitting, you might know. It’s when your legs, at night, try to do all the running you was supposed to do during the day but you didn’t. Anyway, here I am. How about that, you think I’m crazy?” He stood in front of the open refrigerator, the cold, colorful food steaming behind him.

“You went to Epcot?” I said.

“Yeah. Where was I supposed to go? Hey, you don’t have to leave or nothing,” he said.

“I’ve got to get going,” I said.

“Say, where’s your girlfriend at? Ain’t that her car out front?” Our family’s poodle had died like this, when I was a child: she ran out onto the two-lane highway, then froze on the center line when she saw the traffic coming. It was impossible for her to go forward and impossible to go back. She stood there in the wind of rushing cars, turning her curly, quivering head back and forth, looking one way, then the other, until a truck finally clipped her, knocking her sideways into the eastbound lane, where a Chevy got her.

“I can’t go up there,” I said.

“Jeannie’s up at your place? Well, tell her to come on down and join the party.”

“Borden,” I said.

“Hey, hey, what’s the matter?” He came back over to the sofa and sat, reaching down and lifting my legs by the ankles, before I could stop him, so that my feet rested in his lap. Once they were there, I thought it would be cruel to yank them off; I didn’t want to hurt his feelings. His big thighs felt synthetic, slippery and impersonal as upholstery against my bare heels, and I imagined Jeannie watching from the doorway, the little sarcastic points of her eyes and mouth and naked breasts. “I’ll tell you what,” Borden said. “You’re okay, CeCe. At least you got some integrity, some principles. You’re the first one so far who ain’t tried to get some of the prize for yourself. How about that? You thought I was too big and fat for you before and now that I got the cash, I’m still too big and fat. What do you know?”

“Hello, Tom, it’s me again.” He gazed, confused, at the wall telephone instead of at the whirring machine, where the woman’s voice was coming from. “I don’t want to use up your tape over nothing, but you won’t believe what just happened to me. I was coming out of Winn Dixie —

“I was just at Winn Dixie!” Borden said.

“She can’t hear you, why don’t you — ”

“Shh,”he said.

“— out of Collins mix, but I only had one, I said it before I went out, I said, ‘Frieda, tonight you will behave like a lady.’ So I told the officer I was celebrating for you, I said, ‘Officer, I am not in my normal mode,’ but he didn’t even believe I know you! He said, ‘Right, lady,’ and then he grabs my arm real hard, and I told him, ‘Don’ t you put your hands on me! When I tell you to put your hands on me, you do so with gusto, but when I say,’ and he says, ‘Oh, the lady’s got rules!’” She paused, swallowing, and the machine cut her off.

“You can pick up the phone while she’s talking,” I told Borden, but he just sighed, his thighs giving a little under my feet as though some of the air had gone out of them.

“I know I’m supposed to be celebrating,” he said, “but man, everybody wants something, you know?”

“Not Frieda,” I said.

“What do you know about Frieda?” Borden said. He dug his thumb into the soft ball of my foot and I tried to jerk it away from him, but the cushions under me were soft and I couldn’t get any leverage. “A Chinese girl did this to me one time,” Borden said. “Something-su, I forget what it’s called. You’ll like it.”

“Please quit that,” I said. “All I meant was, Frieda seems to respect and depend on you.”

“Naw, she don’t love me. She just wants attention, you know? Her old man’s in jail, over in Starke, HRS got her kids, and she ain’t even allowed in half the bars in the county, because she’s always looking at someone’s husband and licking her straw. I seen her get a black eye for doing that. That’s why she comes by here, because she don’t got nowhere else to go, you know what I’m saying?”

“I don’t want to know about Frieda,” I said. “Maybe she likes her life, maybe she likes not having any responsibility, not having to worry about anything — ”

“Naw, she don’t,” Borden said. “Nobody wants everything taken from them. Everybody wants some give.” Frieda had come back on, meanwhile, saying something about Weight Watchers, but Borden spoke right over her — rudely, I thought, even if she did want something from him. “You want to hear something nuts?” he said. “When I got this thing confirmed, that I really hit it big, what’s the first thing popped into my head? Breeder tank. Number one, my breeding females been dying, I gotta get some more, and a breeder tank. Number two, this tie I saw on TV, one of them shopping shows, some kind of a silk weave. I mean, does a Porsche occur to me? No. Yacht? No. Paris, France? Forget it. Girl I took out in high school whose old man was a commie, he was always asking me what was my ambition, because he knew. He knew I didn’t have none. He told me, he said, ‘This is how they keep you down — whatever you got, you think that’s all you deserve.’ You get so you only see one inch in front of your own face, he said.”

“Well, what are you going to do?” I said. Borden took his damp hands off my feet and pressed them over his eyes, then combed them back through his thin hair over and over again. He stared across the room at the hovering mollies. “You know what?” he finally said. “I just want to think about it tomorrow.”

“Borden, I need to ask you a favor,” I said. “Only certain things need to be clear up front. It’s not money or anything . . .”

“You can stay here, just go on back to sleep, don’t worry about it,” he said, before I could go on. He stood up and walked with his hands in his pockets over to the window. “Don’t worry about me,” he said. He cupped his hands like blinders against the glass to block out the reflection of the lamp and sighed, making a small patch of steam. “I’m a perfect gentleman,” he said.

In the morning he was gone. A note taped on the aquarium glass said: I went back to You Know Where. I don’t want to disturb your beauty sleep. Please feed the fish, O.K.? I found my boots in the kitchen and left, shutting the door quickly and quietly, as though someone were still in the apartment, sleeping.

I got Jeannie out of my bed and we sat at my kitchen table, smoking cigarettes over plates of eggs. The professor had left right after I’d gone back downstairs to Borden’s, she said. She suggested we spend the day together, go to a street fair or maybe go see the royal stallions that walked around on their hind legs. “Or how about that Wet Water place you applied at?” she said.

“We’re too old for that shit,” I said. “People have heart attacks there.”

“Well, I’m paying,” she said, “so decide.”

At the dog track, where we ended up, she bought me some popcorn and then ran off to the clubhouse to say hello to a jai-alai player she knew. I stayed in the stands, trying to understand the loud announcer, the endless blur of greyhounds whipping by behind their strange fuzzy lure, but after Jeannie had been gone awhile I gave up and stared at the crowd instead. An unexpected hot wind had come up off the Gulf, and people were sitting on their wadded-up jackets and mopping their foreheads with concession napkins. So many of them resembled Borden, I thought — so many lumpy bodies and damp, hungry-looking faces. Right in front of me a man who could have been Borden had stood up and was unzipping and peeling off one sweatshirt after another like a birthday party magician pulling scarves out of a sleeve. Maybe it was an effect of the sun, or the pony sofa smell steaming off my hair, but each time he got another sweatshirt off and revealed yet another one, underneath, my scalp prickled with anticipation, as though we were all there to bet on sweatshirts instead of dogs. I thought of the real Borden wistfully, as though it had been a long time since we had seen each other, and I wished he were there with me, watching; I imagined his damp, gentlemanly face happy for once, laughing, finally, at his own good fortune.

Tags

Wendy Brenner

Wendy Brenner lives in Gainesville, Florida. (1994)