Protest Music

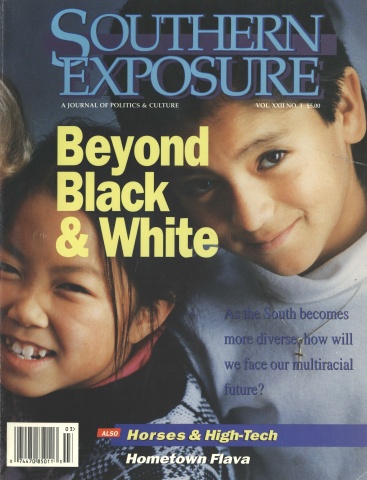

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

Young African Americans from around the South form a circle with veterans of the civil rights movement. It is Saturday night, the close of a workshop at the Highlander Center near Knoxville, Tennessee. “Overcoming” is the theme of the gathering, and the participants end the evening by singing a rap the young people created based on the civil rights anthem “We Shall Overcome.”

I overcome . . . the slums, ghettos in decay

I overcome . . . adversity always coming my way

I overcome . . . so many evils and so much hate

I overcome . . . those suckers who discriminate.

The young people and their rap song are part of a long and vibrant movement of musical protest in the region. Generations of talented songwriters and singers have used their pens and their voices to highlight injustices in their communities. Using humor, satire, poetry, sharp analysis, anger, and sometimes hope, these musicians have chronicled the most pressing problems of the South and inspired millions working for social and economic change.

Protest music emerged as a genre in its own right during the 1930s, when Southern workers crafted socially conscious songs as a weapon in their labor struggles. In the Mississippi Delta, John Handcox armed his fellow sharecroppers in the Southern Tenant Farmers Union with “There Are Mean Things Happening in This Land” and “Roll the Union On.” In Kentucky, Florence Reece stung the enemies of Harlan County miners with “Which Side Are You On?”

Throughout its long history, Highlander has encouraged grassroots activists to put music at the center of the struggle. Zilphia Horton drew songs from people at Highlander workshops during the 20 years she worked at the center. She loved and encouraged traditional music and urged people to write new words when the old ones didn’t address their daily concerns.

Horton was at a Highlander workshop in 1945 when some women from Charleston, South Carolina brought “We Will Overcome” from a food and tobacco workers strike. They had already adapted the religious “I’ll Be All Right Someday” to suit their picket line. Horton in turn introduced “We Shall Overcome” to countless community and union groups as she traveled the South.

Horton and the center served as a bridge between the earlier generation of protest singers and the emerging civil rights movement. Black activists reworked older religious and folk songs to sustain them on marches and in Southern jails, and their stirring music found its way into American popular culture.

Our own work as singers, songwriters, and organizers built on the methods of Horton and Highlander. The center encouraged us to organize workshops for people engaged in community campaigns to challenge social ills — including segregation, unfair working conditions, and environmental destruction. Each era, each issue, each campaign and struggle produced its songs.

Two Appalachian songwriters who attended a recent workshop on environmental culture demonstrate the power of protest music in the contemporary South. Elaine Purkey grew up in the coalfields and can touch her audience deeply with the traditional ballads and gospel songs of West Virginia. It’s her contemporary labor songs, however, that best express what she cares about today. When community groups or unions call on her to tell their story in a song, she goes. At a 1989 rally by miners in southwest Virginia months before they struck against the Pittston Coal Group, Purkey was there with a powerful alto and a solid guitar.

Kenny Rosenbalm came to a gathering at Highlander in the mid-1980s after organizing a major protest against strip mining in Pineville, Kentucky. He found himself in awe of the Native American elders who sat in the circle, but by the end of the workshop he shyly admitted that he’d written a few songs. Over the next few years Rosenbalm became the unofficial balladeer of the STP program at Highlander (Stop the Poison, Save the Planet, Start the Party, or Shoot the Politician). He listened to people describe their experiences and composed songs based on their stories. His songs are mostly dead-serious, but his wicked humor creeps out in titles like “Paranoid to the Bone.”

The South today is replete with creative people who shape their perceptions and struggles into songs of protest. Bernice Johnson Reagon draws on her experiences in the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee when singing with Sweet Honey in the Rock. Si Kahn still uses music in his work as a community organizer in North Carolina. And youth activists like the Highlander rappers add new styles that help us win age-old struggles:

I overcome . . . the stigma of addiction

I overcome . . . all the media fiction

I overcome . . . with my sisters and brothers

I overcome . . . so in turn we can help others

We overcome!

Tags

Guy Carawan

Guy and Candie Carawan are musicians and cultural organizers based at Highlander. (1994)

Candie Carawan

Guy and Candie Carawan are musicians and cultural organizers based at Highlander. (1994)