This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

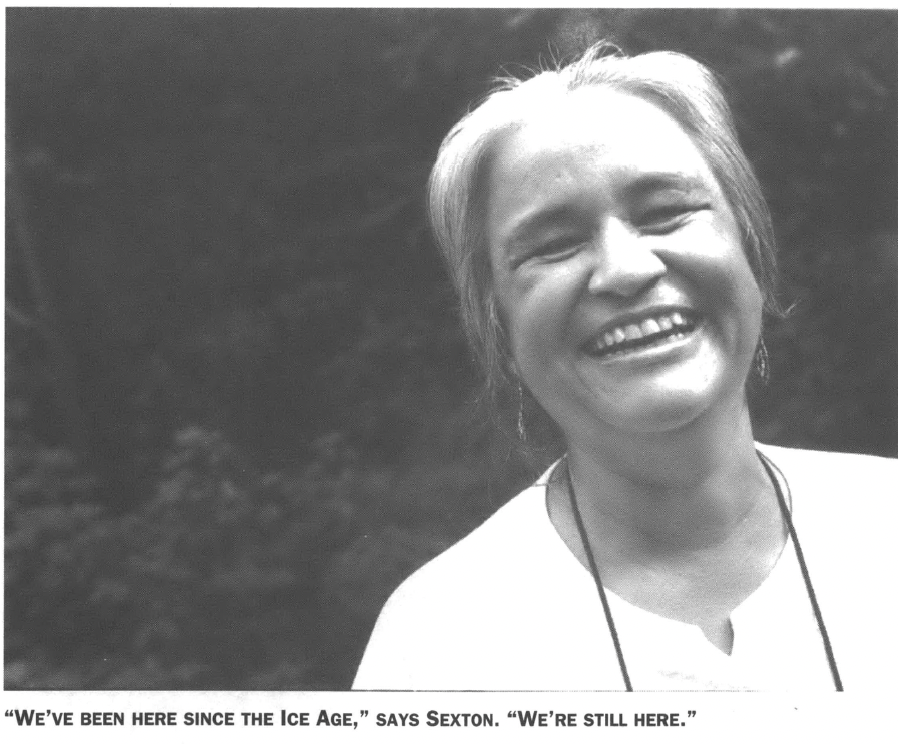

Virginia Sexton grew up in a New York orphanage, unsure of where she was born. Since moving to the Cherokee reservation in western North Carolina 15 years ago, however, she is certain where she belongs.

Sexton traces her ancestry on the reservation back to 1751. Initially she and her husband Mike lived quietly on a piece of family land up Noble Mountain. But her peaceful life ended abruptly when the couple was refused custody of Mike’s white grandson.

“The reservation was shifting from state and federal jurisdiction to the tribal courts,” Sexton recalls. “But it was still the South, and they wouldn’t give a white child to an Indian woman. That would have been a reversal; they usually give away the Indian children.”

Though the Sextons lost their custody battle, the legal struggle spurred Virginia to begin studying law. Gradually, she began to understand what was happening on the reservation. She saw tremendous sums of money flowing in and out, while the majority of the people, particularly the full-bloods and half-bloods, continued to live in poverty. Power, she learned, lay with a small nucleus of businesspeople, many of whom had ensconced themselves on “the res” with unsubstantiated claims to Indian blood.

The Trail of Tears Gallery, the Tsali Motel, the Tepee Electronic Lotto arcade, the grave men who pose for photographs in full headdress — everywhere Sexton looked she saw a commercialized culture, a culture that tribal leaders boast of having worked 50 years to make “the Cherokee tradition.” The tribal council routinely takes land from Native Americans and leases it to businessmen for campgrounds, curio shops, all the blight essential to the tourist trade.

Sexton learned that her own family’s land had been taken away — occupied now, in part, by the amphitheater for Unto These Hills, an outdoor summer drama in which white college students reenact the struggles of the Cherokee. A nearby parking lot covers what used to be a burial ground where Sexton’s ancestors are interred. Using her new-found knowledge of the law, she fought successfully in the federal courts to save the site from total eradication.

Sexton went on to earn her paralegal license, and she and her husband began helping others fight the tribal council. “After five or six years of people coming and saying, ‘The council took my land’ . . . we got politicized.”

The couple formed an organization called Wake-Up, which has successfully fought off an incinerator, a landfill, and a nuclear depository on the reservation. The group has taken its opposition even further by challenging the very legality of the council. Last year, a council committee rejected a constitutional change expanding the tribal roll to those with less than one-16th Cherokee blood. Wake-Up points out that having been elected by this unconstitutionally expanded roll, the tribal council itself— and every business contract it has signed — is illegal.

So far, however, no action has been taken on the issue. “The Bureau of Indian Affairs is ignoring the tribe’s true membership,” says Bob Warren, a civil rights attorney from Black Mountain. “It’s the same old story of buying off the chief to get Indians to do what the white man wants them to do.”

While the “official” roll now totals over 10,000 (one man is listed as 1/1024th Cherokee), Sexton points out that the Eastern Band of Cherokee — those who stayed behind when the Western Band was forcibly relocated to Oklahoma in 1838 — originally had only 91 families. “With all the health problems, alcoholism, the suicide rate, how can we now be 10,000?” she asks. By her count, there are 5,700 true Cherokee on the reservation.

Sexton has run for a seat on the council, but believes that unfair election practices have kept her from winning. When the polls are closed on election day, the council shuts the door and counts the votes in secret.

“Virginia’s been fighting a long time to see that votes are counted in the open,” Warren says. “Unfortunately, they’re still not.”

Both the Carter Center and Amnesty International have expressed interest in monitoring the election next year, and Sexton intends to run — if she isn’t in law school. She’s scheduled to graduate next May from Western Carolina University with a B.S. in Political Science, and the long-term plan is to attend law school, then return to the reservation to take on the council, the local media, and, when necessary, federal officials.

Sexton has also fought gambling on the reservation, helping to force a temporary removal of video gambling machines. Aside from the more obvious concerns about corruption and alcohol, she and many others feel that gambling will disrupt traditional ways of life. As one Cherokee put it, “We will never again see a quiet winter.”

Sexton’s opposition to gambling has incurred further wrath from the powers-that-be, including that of the weekly Cherokee One Feather. But her ongoing struggle for Cherokee rights has also earned her quite a few admirers. In July, she received the Dr. Marketta Laurila Free Speech Award, presented by 11 progressive groups in western North Carolina.

Despite her opposition to commercial development, Sexton understands those Cherokee who sell a parcel of their tradition. As long as they have few economic options, she says, local men will don headdresses to feed their families, and businessmen will attempt to profit from motels and casinos.

“People come to see the Indians,” says Sexton, “and they say, ‘Where are the Indians?’” What she wants is to make her people more visible — to move them out of the mountain coves and into the decisionmaking processes that affect their lives.

“We’ve been here since the Ice Age, since the woolly mammoth,” she says, “We’re still here.”