This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

Joe Hernandez flings a thin rope over a tree branch and catches its end. A cigarette dangling from his lips, he ties the rope to the top of a clown-shaped piñata that stands before a crowd of brown children waiting excitedly to one side. The kids chat to one another in both English and Spanish over who will be the one to crack it open. Behind them the remnants of last night’s kill, a 200-pound pig that Hernandez quartered around midnight and cooked through the early morning hours, lie beside mounds of jalapeno sauce, tortillas, and beer cans. Hernandez sweats as he works on the Mexican toy. The temperature has reached well over 95 degrees today, cooking up the north Alabama humidity.

Others arrive to celebrate his daughter Amalia’s eighth birthday. Men and women from the states of Juarez, Veracruz, Matejuela, Chijuaja, and Oaxaca gather in Hernandez’s front yard, an hour northeast of Birmingham in the countryside of Blount County. It is Sunday afternoon. Work in the chicken processing factories, the tomato fields, and the furniture factories has been left behind for a day. Now it is time to celebrate a gathering of La Raza — literally, The Ancestry.

When Hernandez and his young family first arrived in this part of the South, they encountered few fellow Latinos. Living most of their lives in Texas, they followed the migrant path north, toward New York.

“There was little work in Texas, with so many Latinos doing the same jobs for low pay,” Hernandez recalls. “We thought to move to New York, where we had heard that there was plenty of employment.”

They made it to north Alabama when their money ran out. In Blount County they encountered a Mexican man named Johnny who had lived in the area for years, and who helped them get on their feet. “Our plan was to work here for a couple of weeks, make some money, and get on the road again. We didn’t want to stay. Except for Johnny, there wasn’t much Raza around.”

Two weeks became six years. Hernandez took any job he could find, from working on trucks in shops to planting pine trees for three cents a tree. Gradually, he saw a change in the community. At first, migrants came and went, working the tomato crops for four months and returning to Florida or Texas for the winter. As the years passed, however, a few workers decided to stay in what became known as un lugar tranquilo — a tranquil place. As more established themselves in Blount County, family members followed, finding a community of Latinos — and a place where their culture can survive.

Hearing Spanish on the street and in the stores suddenly became a common occurrence. Local patrones and other native Alabamians could not understand what the newcomers were saying, and felt threatened. To overcome their fear, Hernandez offered free Spanish classes to local residents. Though no one walked out of the class fluent, something else happened: Hernandez made relationships with local police officers, store owners, clinic nurses, and teachers.

Such friendships have come in handy. As more Latinos have decided to remain in Blount County, racial tensions have begun to rise. Though the Mexicans are more accepted by white patrones (Hernandez once heard two bosses talking, comparing “the boys” — Latinos — to the local African Americans, and how “you can get more work for less pay out of the Mexicanos than you can from the niggers”), the Latino population growth has moved from a novelty to an incipient threat. To avert the growing stress, Hernandez has acted as an advocate for his own people.

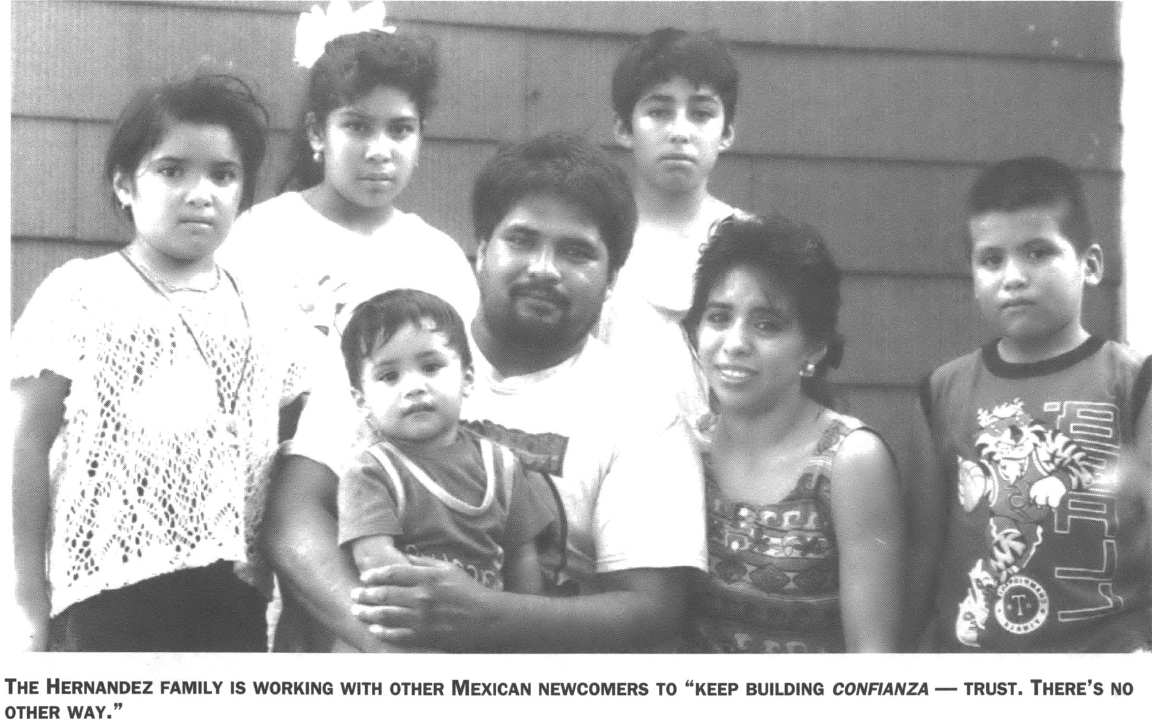

“Sometimes you can clear up a problem between a policeman or a doctor and a Mexican by being there to translate,” he says. “People call me up more, asking for such help. You’ve got to respond. More than anything, you’ve got to keep building confianza — trust — with your own.”

Confianza is getting harder to come by. As the population grows, the white community has relied on fear and intimidation to keep Latinos in check. Immigration raids have become common. The INS has filled trucks with Latino men and shipped them toward the border, visiting trailer parks and apartments with the local police and asking all brown people for identification. Such actions put the Latino community in a panic, making ordinary routines like going to work or attending church on a Saturday evening seem dangerous.

Yet this has not dissuaded Hernandez. He and his wife, along with a few friends, have formed an informal group called Amanecer Latino — Latino Dawn.

“Right now we’re just a small group of friends who get together every week or so and talk about our people’s problems,” Hernandez says. “The fact that Latinos pay $120 a week for rent in a broken-down mobile home, while the whites pay $100 a month in the same trailer park. The fact that our children walk out of school confused and hurt because they’re made fun of when they speak Spanish. The lack of support in local health clinics. We’ve got a lot to deal with. But the way we’ll deal with it is by gaining confianza. There’s no other way to do it.”

At the party for his daughter, the adults laugh while the blindfolded children take a stick to the piñata. Many of the people who eat the pork that Hernandez prepared are folks he has helped out from time to time. It is no wonder that they have come to celebrate this birthday. In this small corner of Alabama, where the traditions of a distant country burst forth in language, music, and food, Joe Hernandez is gaining that communal treasure of confianza.

Tags

Marcos McPeek Villatoro

Marcos McPeek Villatoro grew up in Rogersville, Tennessee, and San Francisco. He is the author of three books: A Fire in the Hearth; Walking to La Milpa; and the poetry collection They Say That I am Two. McPeek Villatoro and his family now live in Los Angeles, where he holds the Fletcher Jones Endowed Chair in Creative Writing at Mount St. Mary’s College. (1999)