This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

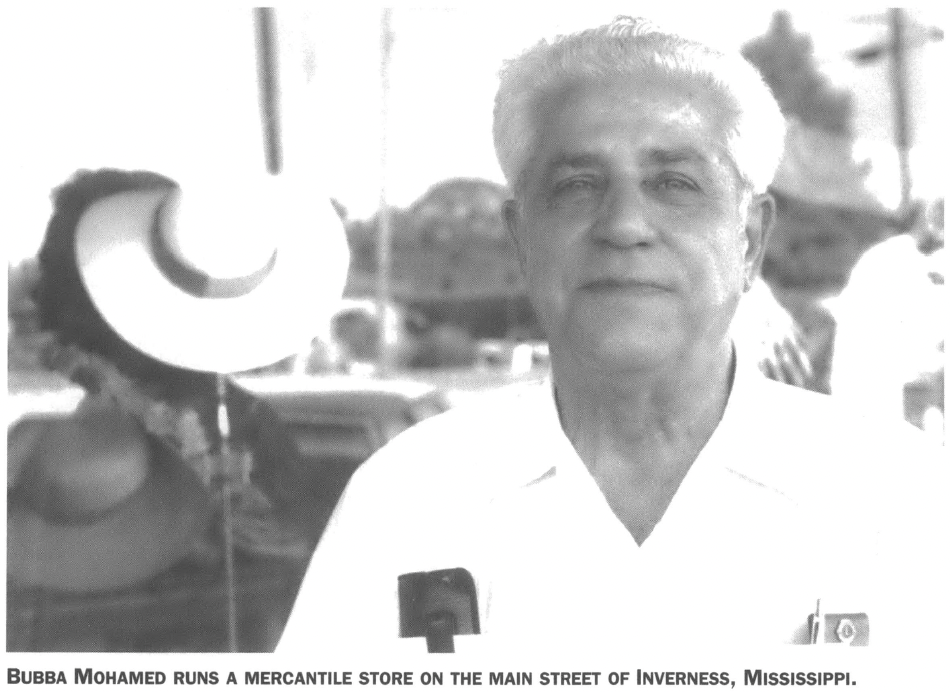

“Bubba Mohamed is my name,” exclaims the wiry man extending his hand as we enter the mercantile store on the main street of the Mississippi Delta town of Inverness. Along the block there are stores named Woo’s Grocery and Wing’s Variety — and Mohamed’s.

“Welcome to the coolest spot in Inverness,” Mohamed continues. “What can I help you with?” Around him are piles of jeans and overalls, racks of shirts and dresses — and t-shirts, too, reading “WHERE IN THE HELL IS INVERNESS MISSISSIPPI?”

“We’re just passing through,” I say, “and thought we’d find out just where in the hell Inverness, Mississippi is”

Mohamed shakes his head for a second, then laughs when he catches my joke. Waving us toward the back, he says, “Come on. Let me show you something.”

Soon we are standing beside his ancient cash register, the kind that museums would steal for. His desk is strewn with mail (the address “Bubba Mohamed, Inverness, Mississippi” is apparently all it takes), the Memphis paper, dry goods catalogues, sales receipt pads, a well-thumbed copy of The Meaning of the Koran.

“There,” he says, producing a colorful museum catalogue. “That’s my mother, Ethel Wright Mohamed. She’s in the Smithsonian!”

The book contains page after page of tapestries she stitched to illustrate the life of her family in the nearby Delta town of Belzoni. Ethel Wright, a woman of hill-country British stock, married one of the earliest Lebanese settlers in Mississippi, a peddler who received the name Mohamed when immigration officials mistakenly put down his religion for a surname.

Mohamed talks for an hour about how his father and brothers chose to flee Lebanon rather than serve in the army of the Turkish Empire. Their trek to Mississippi first took them to Paris, where they worked in a bakery until a cousin, who had come to America and established a store in Clarksdale, sent them money for passage to the United States.

“When my father arrived, his cousin outfitted him with a stock of goods and sent him out as a peddler,” Mohamed says. “It wasn’t long though, before he opened his own wholesale store in Clarksdale.”

When World War I came, there was, as Mohamed tactfully puts it, “friction in Clarksdale.” People thought the Mohameds were Turks, and since the Turkish Empire was on the side of the Germans, threats were made. Rather than fight their neighbors, the family sold the store in Clarksdale and moved to Jonestown, a few miles up the road.

Since then, Lebanese families have become well established in towns along or near the Mississippi River from Vicksburg to Memphis, the route taken by many immigrant groups after they arrive in New Orleans. The largest Lebanese community — in Vicksburg — centers on the St. George Antiochan Orthodox Church.

Founded in 1906, St. George is the twelfth oldest Antiochan church in the country and the oldest in the South. Like Lebanese communities elsewhere, the congregation of St. George has grown steadily in size and prosperity.

Father Nicholas Saikley, who has served as the parish priest for 25 years, greets us in the church foyer. He says there are about 150 families associated with the church — but he is quick to make a distinction.

“You must not confuse the ethnicity of our congregation, which is Lebanese American, with the Orthodox Church, which has no particular ‘ethnic’ identity. In fact, St. George was among the first Orthodox churches in the U.S. to use English in its services, starting in 1925. The early generation needed to leave old ways behind, you see, to become ‘American’: so much so that when I used some Arabic phrases once in a service — it was to greet a visitor from Lebanon, where Arabic is still the official church language — one of the older men shouted from the back, ‘Only in English!’”

Father Saikley laughs. “The people of the Mississippi Lebanese community are the most Americanized in the U.S. — except for food and church, of course.”

Cuisine may truly be the cement that binds the Lebanese to each other, and to the past. Certainly the biggest event of the year at St. George’s is the annual Lebanese dinner, where the community serves up different interpretations of that old staple of Lebanese cooking, kibble. Many recipes for this spicy meat-and-bulgar patty may be found in a cookbook published by St. George that features favorite recipes by local Lebanese cooks. To satisfy the Lebanese chef’s need for such items as bulgar, pine nuts, lamb, and pita bread, many Vicksburg grocery stores — including the big chains — stock shelves with Lebanese staples.

Aside from their neighbors of African and European descent, the Lebanese are the largest cohesive ethnic group in Vicksburg. Storefronts with names like Jabour, Nosser, Thomas, and Habeeb abound — most are mercantile establishments — and the city’s most prominent restaurant, Monsour’s, advertises that it offers Lebanese cuisine.

Father Saikley explains that few Lebanese come from the old country today, “because there is just not as much opportunity for them here as there once was.” Still, the local community remains strong — in part because of its ability to incorporate new members and teach Lebanese ways to the younger generation.

According to Father Saikley, 40 percent of the St. George congregation is non-Lebanese. “Our group absorbs — and embraces — those who marry into it!” he laughs. “As a matter of fact, in all my years as priest, I officiated at only six weddings in which both bride and groom were Arabic.”

After Sunday mass, the congregation gathers for an hour of food and fellowship in a meeting hall just off the sanctuary. We talk with dozens of people about life in Vicksburg, about the church, about being Lebanese, and everyone is eager to share a story. In spite of their “Americanization,” Lebanese culture in Mississippi seems unlikely to pass away.

One woman took me by the arm as we were leaving. “Just remember,” she said. “There’s no such thing as being a little pregnant . . . or a little Lebanese.”