This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

In 1977, the Sumter County Journal announced that a new industry planned to locate in the poor, rural community of Emelle in west Alabama. “New Industry Coming,” the headline read. “New Use For Selma Chalk to Create Jobs.” Rumors circulated that the new industry might be a brick factory or a cement kiln.

The “new industry” turned out to be a landfill owned and operated by Chem-Waste, a subsidiary of WMX, the world’s largest hazardous waste disposal company. Today, the Emelle landfill covers 3,200 acres and accepts waste from 35 states and several foreign countries.

In its early stages, company and local officials speculated that the landfill would attract other industries. Few people doubted their sincerity, and even fewer questioned the notion that any new job is a good job. But while the landfill is now the county’s largest employer and taxpayer, providing 450 jobs and millions in revenue each year, Sumter’s economic base has slowly deteriorated since 1977.

Ten major employers have left the county. Both hospitals have shrunk to little more than clinics. Unemployment jumped from 6 percent to 21 percent, then leveled to 14 percent — largely because 2,000 people have moved away. The income gap between Sumter County and the rest of Alabama has widened, and the infant mortality rate is 70 percent higher than the national average.

Reports of illegal dumping in the landfill and groundwater contamination continue to concern residents. But many say they are afraid to speak out against the dump for fear of reprisals and job loss.

“We’re like toxic waste junkies,” says Mayor James Daily of Emelle. “We can’t live with the landfill and we can’t live without the revenue it brings.”

Sumter is hardly the only Southern community being asked to choose between good jobs and a clean environment. “When you live in a poor area like many of us do, anything is welcomed,” says Mildred Myers of South Carolina Environmental Watch in Gadsden, a community targeted for a number of polluting industries.

“Whenever the subject of environmental protection comes up, we’re beaten back in line by employers telling us that the regulations would cause us to lose our jobs. It’s a no-win situation.”

Good Wood

It’s not easy overcoming the difficulties posed by economic blackmail. Developers and corporations often paint a picture of gloom and doom if their projects are blocked. In reaction, many environmentalists look suspiciously on every economic development plan. But across the South, many grassroots organizations are going beyond the “no-win” face-off of jobs versus environment, fostering a discussion about how communities can have both.

One such group is the Coalition for Jobs and the Environment (CJE), which focuses on a dozen counties in southwest Virginia and northeast Tennessee along the Clinch and Powell rivers. Member groups that had spent years battling the ill-effects of coal mining and timbering on the region’s land and water formed the coalition as a way to show that economic growth can co-exist with ecological protection.

“We were always against things,” says Eileen Mcllvane, executive director of CJE. “We wanted to start having a positive stance about things that could be done as opposed to things that we didn’t want.”

As one of its first steps, CJE organized a meeting of local leaders to begin planning a new approach to combining economic development with environmental protection. With a grant from the state-funded Virginia Center on Rural Development, CJE invited key individuals from five counties in Virginia and five counties in Tennessee to the Clinch Powell Sustainable Development Forum.

“The forum brought in a real cross section of people,” says Mcllvane. “We had small business owners, people from the planning districts, small-town mayors, legislators, and labor unions. We also brought in environmental activists and people from the local chambers of commerce.”

Getting a good mix of participants proved crucial to the project’s success. Many of the business leaders owned small companies or had new ideas they wanted to implement. Through a series of one-on-one meetings, CJE identified a legislator from each state interested in sustainable development.

“Many of the participants still believe in bringing in business from the outside,” explains Mcllvane. “We didn’t say, ‘You’re wrong.’ We said, ‘Will you help us with this other way of doing business and creating jobs?’ So they weren’t giving up the old way of recruiting business, but they came along with the idea and it was a big help.”

Forum participants were divided into groups to study issues of tourism, agriculture, small business, and forestry. After meeting for more than a year, the forum produced a report called “Sustainable Development for Northeast Tennessee and Southwest Virginia.” The document outlines several programs for achieving sustainable development in the bi-state area.

Specific recommendations are made in key areas, including Eco-Tourism, Sustainable and Diversified Agriculture, Regional Information Bank, Land Resources, and Recycled Materials and Energy Efficient Products. The report received wide acclaim, and the forum plans to incorporate and hire its own staff to help implement its vision.

Officials from one of the planning districts involved in the forum are studying how to set up a micro-enterprise network that would allow small businesses to maximize their resources and enter new markets. Other forum participants are developing a regional information bank that would provide data on eco-tours, businesses looking for places to send materials for recycling, and markets for locally produced recyclable goods.

As an example of a new sustainable enterprise, Mcllvane points to a program begun by the Lonesome Pine Office on Youth with a small grant from the Virginia Center on Rural Development. The office teams up youths with unemployed loggers and teaches them a method of lumbering that uses horses to drag the logs after they have been cut. “With this type of logging you don’t need roads or tractors trampling on the forest,” says John Hackett, an independent consultant with the center.

Unlike clear cutting, the process is ecologically sound and creates more jobs. The center is in the process of building a solar kiln to dry and treat the wood. “As a result of the horse logging, using the solar kiln, and a band saw which makes a finer cut, the lumber will be of a finer grade and quality,” says Hackett. The finished product will go to woodworkers, cabinet makers, and craftspeople tapped into the growing market for environmentally sensitive wood products.

In addition to being trained in woodcutting, young people are learning to make professional-quality videotapes to teach others how to log and market environmentally sensitive wood products.

Yet another forum participant, People Incorporated, is using federal funds to provide start-up money for micro-business, eco-tourism, and small business operations. The group also provides ongoing small business training and management for loan recipients.

The Coalition for Jobs and the Environment is raising money to produce a 30-minute video that will document how people in rural Appalachian communities are pursuing sustainable development. According to Mcllvane, the film and an accompanying workbook will provide “real life examples of people doing the work.”

“The idea is to keep the money in the community from start to finish,” says Mcllvane. “Our whole emphasis is to preserve our quality of life. We don’t want to deplete our resources in order to bring up our economic status.”

Wealthfare

Louisiana Citizens for Tax Justice (LCTJ) has taken a different approach to debunk the jobs-versus-environment myth. Through careful research, it has documented how state tax breaks to promote new business investment actually harm Louisiana’s environment and its economic health, depriving communities of much-needed money for schools and social services.

The coalition includes a dozen groups, from feisty regional organizers like ACORN and the Gulf Coast Tenants Organization to labor unions and community groups that cut their teeth fighting the state’s giant petrochemical companies. By focusing on tax inequities and what it calls the state’s “Wealth-fare” system for corporations, the coalition has tapped into Louisiana’s deep populist traditions. It also offers a clear solution for a state still reeling from the oil bust of the mid-1980s: Make the rich pay their fair share, use the money to rebuild communities, and penalize (rather than reward) polluters.

The group’s message is direct and often confrontational. “The rich and powerful WEALTHfare recipients have been taking care of one another for years,” reads a recent LCTJ newsletter. “We will not leave our state in the hands of greedy corporate giants. If we all work together we can take back Louisiana and make it work for the good of all the citizens.”

The central target of the group’s research has been the Industrial Property Tax Exemption Program, which grants new or expanding companies up to 10 years of tax exemptions on their buildings, equipment, and machinery. Government and corporate officials have long praised the program as pivotal in attracting new business investment; any change in the system, they have insisted, would result in massive job loss and plant relocation.

Then in 1986, Oliver Houck, a law professor at Tulane University, authored a study which found that petrochemical companies received 80 percent of all the tax exemptions — but created only 15 percent of the state’s permanent jobs. His study also showed that violators of state environmental laws received tax breaks worth 10 times the potential fines they faced.

“We took what we learned from Houck and took three years to do a study of our own,” says Mary Faucheux, executive director of LCTJ. The resulting 266-page book, The Great Louisiana Tax Giveaway, exposed the fallacies in the jobs-or-environment debate. The study found that:

▼ the state gave away $2.5 billion in tax breaks to major polluting industries, which in turn cut their payrolls by 8,000 jobs.

▼ only 11 percent of the projects receiving tax exemptions created more than 10 jobs; one third added no jobs.

▼ nearly all the tax breaks went to existing plants for expansions or routine maintenance; only six percent went to companies building new plants.

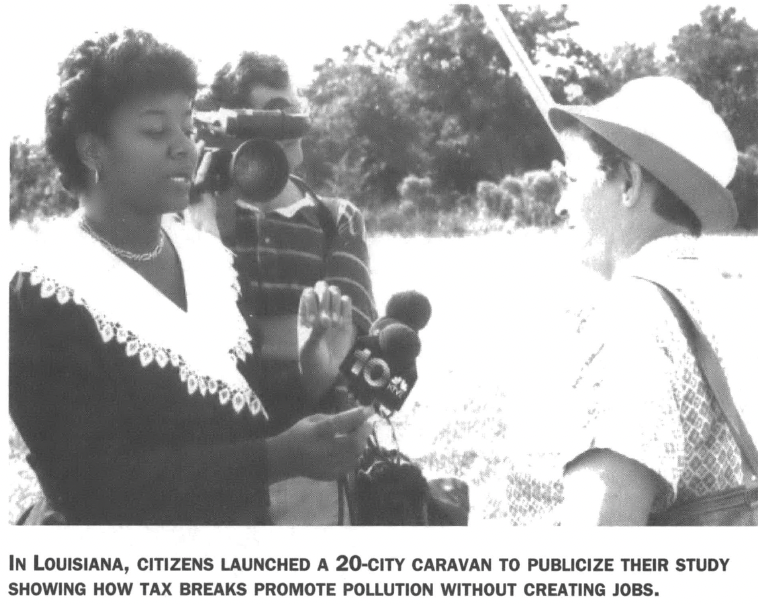

More than just a statistical exercise, the study provided a valuable educational tool that capped three years of organizing and research. “We coordinated a 20-city tax caravan through the state to announce the publication of our book and to distribute it as well,” says Faucheux. “We gave free copies to school board members, mayors, council members, and legislators. We wanted them to look at the revenue we’re losing and see the impact of these tax breaks on people’s lives.”

Students in grades K-12, for example, lose $100 million a year through industry tax breaks, fueling school deficits and teacher layoffs. Armed with this data, state Senator Cleo Fields sponsored a bill to eliminate the school tax exemption in 1991. Citizen lobbying spearheaded by LCTJ helped get the bill through committee, but the measure was defeated on the senate floor. A similar bill died after a bitter fight during the 1994 state legislature.

In spite of these defeats, the coalition has gained a broad array of allies, from teachers to public housing tenants, and it continues to make tax exemptions a public embarrassment for state officials. Early in its life, the coalition won a major victory when Governor Buddy Roemer enacted an “environmental scorecard” that linked the tax benefits a company received to the pollution it produced.

Among other things, the scorecard measured the ratio of an applicant’s toxic chemical emissions to workers on its payroll. Dr. Paul Templet, creator of the scorecard and head of Roemer’s environmental protection agency, defended his “Emissions-to-Jobs” ratio from charges that it would chase chemical companies out of Louisiana.

“They’re not going to leave the state,” Templet told a reporter. “They’re making so much money it’s unbelievable.”

When the industry-dominated state agency that awards tax exemptions fought full implementation of the scorecard, LCTJ waded into the center of the debate. The coalition targeted the application of one company that had omitted mention of its fine for a large chemical spill. Demonstrations by LCTJ supporters sparked a series of agency meetings and more than 200 news articles. Governor Roemer was forced to halt all tax exemptions for several months, and citizens received a rare education in the intricacies of a small agency that cost them billions of dollars.

Although the scorecard was poorly enforced and eventually dropped after Governor Edwin Edwards was elected in November 1991, it succeeded in pressuring companies to clean up their act. The scorecard is credited with stimulating new investments in pollution-prevention equipment that have increased jobs and reduced toxic emissions and air pollutants by 177 million pounds.

LCTJ is now pressuring local officials to fight the tax breaks by sharing how their communities have been hard hit by declining taxes, job loss, and pollution. It also continues to help local groups battle environmental and labor abuses by corporate “Wealthfare” recipients.

“This is a complex problem, so it’s hard to explain to people,” says Faucheux. “What we try to do is to get across to them that there are alternatives. We’re not asking industry to pay more than they should, but their fair share.”

Having a Voice

Next door to Louisiana in Austin, Texas, another group is also promoting state and local policies that balance economic growth with environmental protection.

PODER — People Organized in Defense of the Earth and her Resources — began in 1991, following the arrival of several high-tech companies in East Austin’s predominantly Latino and African-American community. Companies like Motorola and Apple Computer were moving in from Silicon Valley in California, so PODER linked up with the Silicon Valley Toxics Campaign and other groups to learn more about their new neighbors.

“We have some of the leading high-tech companies here in East Austin, and other industries locate here to provide services to them,” says Antonio Diaz of PODER. “We felt that it was time we started to look at how the development of these industries was affecting Austin. The more we learned, the more our members realized we need to address the social and economic impact of high-tech companies, as well as the potential health hazards.”

PODER also began pulling together a broad coalition of Latino, African-American, and environmental groups to reform the city’s policy of granting tax abatements to industries settling in East Austin. The city council began the two-year program in 1989 to stimulate business investment in an area with the city’s highest unemployment rate.

As the program neared its renewal deadline, research showed that it had helped attract 12 companies promising an estimated $1.2 billion investment and 6,857 jobs over the next decade. But only 84 workers had been hired in the initial two years, and one firm that received $14 million in tax abatements pledged to provide only 14 jobs.

PODER learned that many of the companies, while marketed as high-paying and clean, had a history in California of exploiting workers, particular Asian and Latina women, by exposing them to highly toxic substances. The group also learned that several companies settling in East Austin were responsible for toxic sites in Silicon Valley targeted for federal Superfund cleanup.

“We got together with some other groups in the area to discuss these issues and look at our common interests,” says Diaz.

Slowly other groups began expressing interest in the coalition’s work, including such mainstream environmental groups as the Sierra Club and Audubon Society. “It was a bit more difficult convincing them of the interrelationship between so-called economic development policies and the broader impacts,” says Diaz. “We brought them in by addressing the impact the new work force coming to town would have for new housing developments and apartment complexes.”

After a series of meetings, the coalition presented the city council with 14 recommendations to improve the tax abatement program. PODER recommended increasing public participation in awarding abatements and requiring companies that received tax breaks to ensure worker health and safety, obey environmental regulations, inform the community of toxic threats, and hire more local labor.

“Strategically, we discussed the importance of developing these recommendations as opposed to just saying this is a bad policy and the city should do away with it,” says Diaz. “We worked on the recommendations because an aide for one of the councilmen told us outright they weren’t going to do away with the tax abatements. They felt that if other cities were using the abatements, they had to do it, too.”

In meetings with city officials, tensions nearly boiled over. “We just want to have the right to participate, and to have a voice in what’s coming into the community,” Susana Almanza of PODER declared at one meeting.

The climax came at a public hearing in November 1991. East Austin residents detailed their 14 recommendations for improving the tax abatement program, but business leaders wanted even fewer restrictions.

“It’s clear there are some economic storm clouds on the horizon, the most obvious one being the closure of Bergstrom Air Force Base,” said Glenn West, president of the Austin Chamber of Commerce. “This is no time to get cocky.”

But citizens won a partial victory. The city required companies to hire more local workers and abide by all federal, state, and local environmental regulations — “something they should have done in the first place,” notes Diaz.

With the recent economic upswing in Austin, city officials have ended the abatement program. But since the council is now seeking federal “empowerment zone” status, PODER and its allies are considering revisiting the 14 recommendations as criteria for judging investment decisions under the new program.

“I think what we did around the tax exemption ordinance is applicable to empowerment zone situations,” says Diaz. “It’s important to see what kinds of subsidies the city might be giving industries and using that as a hook to bring up broader issues of social, economic, and environmental impact. Too often low-income communities and communities of color are not part of the policy debate where we can articulate what we think is best for our communities and what is sustainable for us.”

As in Appalachia and Louisiana, PODER’s experience illustrates the importance of defining what the community is for as a way of overcoming the false choice between “good jobs” and a “clean environment.” Detailed research is an essential part of the process, but to succeed, citizen groups must ultimately redefine the issues and refocus the conflict into political strategies that speak to the needs of their communities.

“Industry uses job blackmail to keep people from speaking up,” says Mary Faucheux of Louisiana Citizens for Tax Justice. “They say that without the tax exemptions they’ll leave. But we have the river, natural resources, and the cheap labor they need. They’re not going anywhere because they’re making millions of dollars each year. When people realize this, they’re in a better position to stand up to this type of intimidation.”

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.