This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

By the time Luis Humberto Yax-Patzan walked across the border from his home in Guatemala into Tapachula, Mexico, he was already caught up in a current of Central Americans moving north.

“I just followed people,” Yax recalls. “When you get to the frontier with Mexico, you find that there are a lot of people that know what to do. I was trying to do what other people were doing, because they said they were going to the United States.”

Yax left Guatemala with no plan, no map, no destination. In his pockets he had about $150 in Quetzales. His problems had started several months earlier, on June 14, 1991. That afternoon, when he and a fellow high school student left the National Library in Guatemala City, they were ordered into a car by two men, beaten, and interrogated about their work as leaders of the CEEM, the city-wide student coordinating board. As student body president, Yax was automatically a member of CEEM, and its protests of school conditions had attracted the attention of the government.

Yax was left in a remote section of the city; his companion was released later. “I knew I was very lucky,” Yax says. “Usually they kill you.” After hiding for two months, Yax took a job in a Guatemala City factory. When he saw the same car in which he had been abducted parked outside the factory on two occasions, he quietly left the country. His first day in Mexico convinced him that he didn’t belong there, either. When the train he was riding slowed to a stop at the first large Mexican city north of the border, men who wore badges and identified themselves as Mexican Federal Judicial Police entered the boxcar in which Yax and 15 men, women, and children were riding and robbed them. The officers then took them to another location along the train tracks, showed them where the next train would slow down, and allowed them to continue.

“They confused us,” Yax says. “When we took the train where they told us, we were going back. We saw a city that we already passed.”

Three weeks later, Yax reached the town of Nuevo Laredo near the Texas border. His money gone, he had only the clothes he was wearing. Although his Guatemalan accent and Mayan features belied his claim that he was a Mexican, he convinced a construction foreman that he was “from San Luis” and was hired as a laborer. “I wanted to work for a week and go to the United States,” he says, “but they didn’t pay us until after four weeks.”

After sleeping in the trainyards and living off the small kindnesses of strangers for a month, it was finally time to cross over into Texas. Yax followed his instincts — and the people.

“A bunch of people said we’re going to cross tomorrow,” he says. “So the next day, after they paid me, I crossed the bridge. That was Christmas, or the 24th — a lot of people from Mexico were going to shop in the Unites States. The bridge was full of people and I just walked. They didn’t check, I mean, they got confused, and that’s how I came here.”

Three days later, while sitting in the plaza in Laredo, Texas, Yax was detained by the Border Patrol and taken to a shelter for underage INS prisoners in Raymondville. Two months later — three days after his 18th birthday — he was released into the custody of a ranch owner from Austin, who signed him out of the shelter and agreed to provide room and board in exchange for work at his riding stable.

“We worked 12 hours a day,” Luis says. “We got food, but not enough, and no pay.” When he asked if he could call his mother in Guatemala, the owner told him he could not use the phone. “I was writing letters and stuff like that, but then I couldn’t mail them. The stable owner said, ‘You can give them to me and I will mail them.’ My mom told me later that she didn’t never receive anything.”

After three weeks, a Spanish-speaking customer finally came to the stables. When Yax told her what was happening, she took him to the St. Louis Catholic Church in north Austin. There a parish priest drove him to Casa Marianella, a 10-year-old sanctuary founded at a time when refugees, most fleeing death squads and the military in El Salvador, were pouring into Texas.

“I remember looking up and seeing this forlorn kid, with his glasses sliding down his nose,” says Terri English, the sanctuary director.

Yax was fortunate to wind up in Austin, where Catholics, Quakers, Latin American scholars, public interest lawyers, and a growing number of Central Americans have created a safe haven for refugees. Through Casa Marianella, Yax connected with the Political Asylum Project of Austin, where a volunteer attorney prepared his application for political asylum.

He was also fortunate to have evidence to prove his case. Yax called home and asked his mother to retrieve the death-threat notes left folded under the clothes in a chest-of-drawers. The next day, a professor from the University of Texas Latin American Studies Institute who was working in Guatemala picked up the notes and spent a day looking up the local newspaper account of Yax’s abduction.

“He had documentation that most political refugees that these things happen to never have,” says Charlotte McCann of the Documentation Exchange, an Austin-based human rights organization that assists attorneys representing asylum applicants.

The evidence was enough to convince San Antonio immigration judge Bernabe Maldonado that Yax had a well-founded fear of persecution by government agents in Guatemala. In September 1992, the judge granted him asylum.

Earlier this year, Yax graduated from Johnston High School, passed the state exit exam on the second try, and spent his second summer working as a playground supervisor for Austin Parks and Recreation. In August, he began classes at Austin Community College, where he is enrolled in English Composition, Biology, and Algebra. He and another young Central American refugee are sharing a room in the house of an Austin man they met through Casa Marianella.

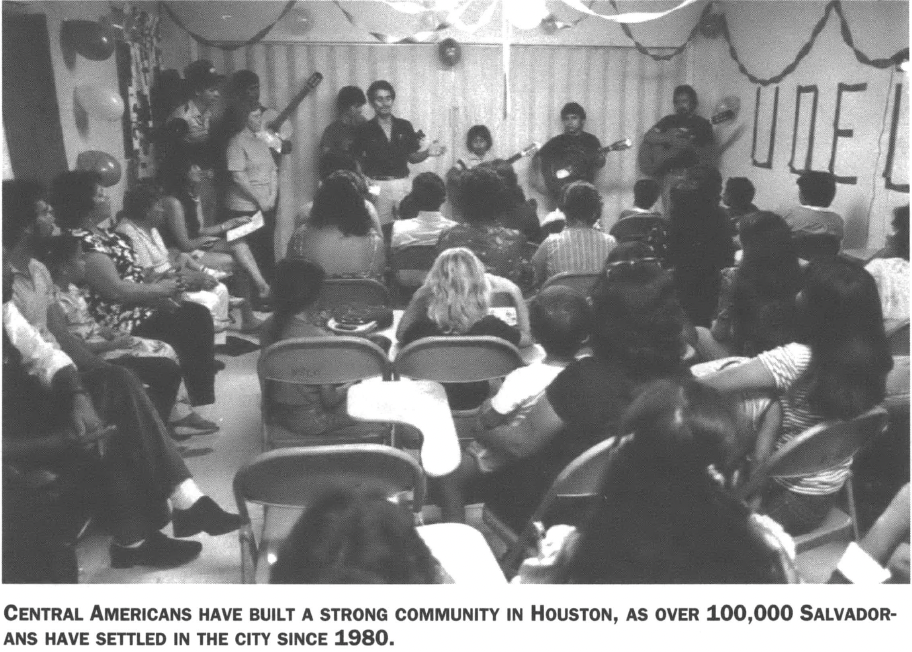

If fate had worked to send Yax to a horse ranch in Houston, he might have found his way into one of the largest Central American communities in the South, shaped by the 100,000-plus Salvadoran immigrants who arrived during the 1980s. In Austin, an estimated 5,000 Central Americans are just beginning to develop a nascent community around the first home Yax found in the city. “When I want to talk to Central American people,” Yax says, “I go to the Casa.”

Beyond Casa Marianella and other organizations that provide immigrant services, however, the Central American community tends to get lost in the established Chicano/Mexicano barrio in southeast Austin. All that exists now is “a network that we use to find jobs, to get immigration help, to find transportation,” says Juan Cabrerra, a Salvadoran community activist who has lived in Austin for four years.

To build a more cohesive community, Cabrerra and other activists have formed a group tentatively called Hispanos Unidos. “We all confront the same problems and we need to confront them together,” he says. “We have about 200 names. It is a beginning.”

The organization, which held its first meeting in September, wants to connect Central Americans already established in Austin with those just arriving. “A common problem when there is no real barrio is that older immigrants turn their back on newer immigrants,” says Cabrerra. “We are going to try to bring the two groups together.”

Such an organization would certainly have eased the transition for the thousands of kids like Yax who have made their way by pluck and luck from Central America to Texas over the past decade. Kids like Evelyn Rocha, a Nicaraguan child whose hired coyote dropped her off in the Chihuahuan desert and said “from here you walk.” Or Olger Rodriguez, another Nicaraguan who at 12 left his home with a handful of American dollars and ran the Laredo bridge rather than cross the river because his 13-year-old sister couldn’t swim. And Luis Humberto Yax-Patzan, who “followed the people” just as African-American slaves once “followed the drinkin’ gourd.”

Yax says he has no idea when he will go back to Guatemala. Death threats have continued against CEEM members, and in June the government accused the student group of gang vandalism in Guatemala City.

“I won’t go back until I have a diploma,” Yax says — which he calculates will include two years at the community college, two years at the University of Texas, and several years of graduate school. After he won his asylum case, he decided to study law. “Now, I’m thinking about medicine,” he says.

Three years after he crossed the Mexican border, he has just completed his application for permanent residence.

Tags

Louis Dubose

Lou Dubose is editor of The Texas Observer, and Ellen Hosmer is editor-at-large of Multinational Monitor. Names of Mexican workers quoted in this story have been changed to protect them from possible reprisals by their employers. (1990)