Gold & Green

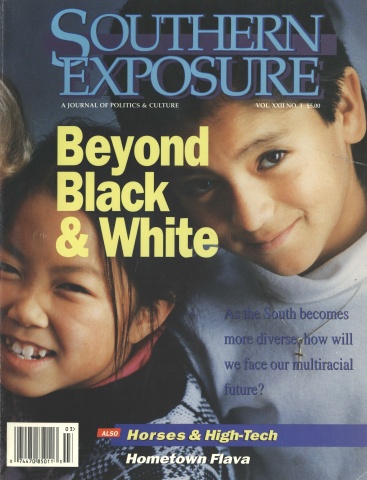

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

SCENE ONE: To convince Mercedes-Benz to locate a factory in Alabama last year, state officials hand the automaker more than $300 million in incentives, including free land, wage subsidies, and 25 years of income-tax exemptions. The package will cost Alabama at least $153,000 per promised job.

SCENE TWO: The same year, a judge declares Alabama’s cash-starved school system unconstitutional because it fails to give children an adequate education. Schools get most of their money from property taxes, and Alabama’s are the lowest in the nation, thanks to steadfast lobbying by large farm and timber landowners.

SCENE THREE: Timber companies, encouraged by low taxes and lax regulations, slash more Alabama forests and begin the ecological madness of riverside chip mills. Pulverized trees are shipped to Mobile and then to Japan, where workers turn them into wood products for the Far East. Alabama loses jobs and its trees. “Witnessing the amount of active deforestation in Alabama was much worse than any experience I’ve had in the rainforests of Central America,” says Daniel Dancer, a photographer who has documented the destruction.

These three scenes in one Southern state underscore what’s wrong with the traditional approach to economic development. Instead of treasuring natural resources and using them to promote sustainable development, officials continue to discount their true value. The subsidy strategy benefits corporations, but imposes a huge cost on taxpayers, school kids, workers, and the environment.

Perhaps to mask the human and environmental cost of their policies, Alabama leaders keep the focus on “outsiders” (federal regulators, labor unions, foreigners), happy for the occasional bit of good news. “There’s a great feeling of elation that the Mercedes facility is coming,” says Barry Mason, dean of the College of Commerce at the University of Alabama. “Any time you can bring in good wages and steady employment, you’re not talking about destroying the quality of life, but of enhancing it.”

Such thinking is common — and dead wrong, according to the Rocky Mountain Institute. Working in dozens of communities across the nation, the non-profit group identified three fallacies in the conventional approach to economic development: “(1) decisions are best when they’re made by . . . the small group of old white men who have always made the decisions; (2) communities must sacrifice their environment in order to get jobs, and (3) in order to prosper, communities must recruit outside businesses.”

The staff of the Institute — including economists and noted scientists like physicist Amory Lovins — aren’t inclined to radical rhetoric. But they have little tolerance for habits of thinking or behavior that obstruct genuine problem-solving.

Sacrificing the environment for jobs is just stupid, says Michael Kinsley of the Institute. “When we use our resources and other assets faster than we renew them, we treat them as if they’re income. That’s lousy accounting . . . like a dairy farmer selling her cows to buy feed.”

Green Growth

For too long, the South has been selling its future like Kinsley’s farmer. Decades after the oil embargo and Club of Rome’s report on suicidal growth rates, most Southern cities lag well behind their national counterparts on recycling programs, and reducing toxic chemicals is considered a threat to economic prosperity.

“There’s been lots of talk, but not much done to either reduce those emissions or determine which are causing the most significant public health risks,” says Alan Jones of the Tennessee Environmental Council.

Proponents of stricter protections for public health are constantly told they’re jeopardizing jobs. “Corporations use economic blackmail as a club to keep people quiet,” says Richard Grossman, co-author of Fear at Work. “It’s a tactic to divide and intimidate, but it has no justification in fact.”

What is the real connection between a healthy economy and healthy environment? Can a state with strong conservation standards provide good jobs and outperform the subsidy-based development strategy typified by Alabama?

To find out, Southern Exposure and its publisher, the Institute for Southern Studies, collected two sets of indicators — one measuring job quality and economic vitality, the other measuring stress on the natural environment. The 20 economic indicators emphasize job opportunities, working conditions, protection for disabled or unemployed workers, and job creation. The 20 environmental measures focus on toxic emissions, recycling efforts, and state spending to protect natural resources.

We ranked the states based on each indicator, and produced an overall score for each state by adding up its individual ranks. Comparing the two lists reveals a remarkable correlation:

▼ Louisiana ranks dead last for jobs and for environmental quality. Eight other Southern states (along with Indiana, Oklahoma, and Ohio) rank among the worst 14 in both categories.

▼ Hawaii, Vermont, and New Hampshire rank among the top six on both lists. Six other states rank among the best 12 on each list: Wisconsin, Minnesota, Colorado, Oregon, Massachusetts, and Maryland.

▼ New England and the Scandinavian-influenced states rank best on both sets of indicators, perhaps reflecting their progressive political heritage. Similarly, states that rank best on the bellwether indicator of infant mortality generally score high on both our lists.

▼ The states most dependent on mining and oil wells generally fair poorest on both lists, no doubt reflecting a political tradition that tolerates resource exploitation.

There are a number of important exceptions, but the overall picture is clear: The best stewards of the environment also offer workaday citizens the best opportunity for prosperity.

Our findings confirm earlier research by Dr. Stephen Meyer of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, who tracked 20 years of economic performance by state. His conclusion: “States with stronger environmental standards tended to have higher growth in their gross state products, total employment, construction employment, and labor productivity than states that ranked lower environmentally.”

In 1993, Meyer updated his data and used our 1991-92 Green Index as a measure of each state’s commitment to conservation. Again the numbers refute the myth that environmental protection harms job growth. “If environmentalism does have negative economic effects,” he says, “they are so marginal and transient that they are completely lost in the white noise of much more powerful domestic and international economic influences.”

In other words, a particular factory may be so marginal that the cost of environmental controls pushes it over the competitive edge, but the demand for safeguarding public health is not to blame. A facility this fragile is operating on borrowed time, forcing someone else (taxpayers, workers, downwind residents) to subsidize its true costs to the environment and public.

Identifying — and ending — hidden subsidies for pollution would dramatically advance sustainable development. “If we were forced to pay the cost of acid rain in Canada, or include the cost of Middle East defense in our utility bills, I think society would likely alter its energy choices,” says Karen McCarthy, president of the National Conference of State Legislators. Dr. Paul Templet of Louisiana State University has studied several hidden subsidies which states absorb on behalf of their polluting industries. In each case, the subsidies actually hurt the economy rather than create good jobs. For example, states that allow industry to spend below the national average on pollution-control equipment have the weakest economies (see Indicator #19 on our “Poisons and the Environment” chart).

As head of the Louisiana Department of Environmental Quality from 1988 to 1991, Templet created a handy indicator for measuring the cost-versus-benefit of a polluting industry. His “Emissions-to-Jobs” ratio became a hot political potato, but he has since expanded his research and says the indicator offers an excellent barometer of a state’s overall health. The ratio simply divides the toxic chemical emissions of a state’s manufacturers by its number of manufacturing jobs. Vermont’s 1991 ratio is 24; Louisiana’s is 2,623.

Templet has found strong statistical correlations between the ratio, environmental subsidies, and such social indicators as poverty, unemployment, and income disparity. “The subsidies are generally paid by the public, and indicators of public welfare and environmental quality decline as the subsidies increase,” he writes. “The state becomes poorer, more polluted, less diversified, subject to boom and bust economies, and more reliant on the very industries which are reaping the subsidies.”

A New Initiative

Fighting subsidies is an effective strategy for building alliances that can negotiate for environmental equity and alternative economic development (see “Horses and High-Tech,” page 53). The harder step is building a new political culture that supports sustainable development through broad policies and specific projects.

Success requires inverting the three development myths identified by the Rocky Mountain Institute: Sustainable programs must (1) engage ordinary people so they can become decision makers and teachers of future community leaders; (2) integrate respect for the environment with respect for basic human needs; and (3) recognize a community’s natural and human assets as its core strength.

Fortunately, dozens of organizations are putting these principles into practice. Many are young and small, and their resources pale compared to the billions poured into promoting old-style economic development. But they hold great promise as examples for what local communities can do.

To strengthen these bottom-up efforts and share their lessons, the Institute for Southern Studies has launched a Community Development Initiative that includes forums, reports, training, resource mobilization, and targeted research. The CDI creates a partnership with grassroots leaders engaged in solid community-building programs — health clinics, housing, youth programs, worker organizing, job development, environmental planning, political education. Isaiah Madison, executive director of the Institute, has already coordinated a survey of 50 leaders from across the South and convened a mini-conference in August to begin charting the next steps of the collaboration.

While the Institute continues its hard-hitting investigative research, the new initiative recognizes that we can’t settle for simply naming the problem. We too must be proactive, developing solutions that overcome false divisions with the common goal of environmental and economic justice. It’s slow, hard work, but that’s what sustainable development is all about.

Tags

Bob Hall

Bob Hall is the founding editor of Southern Exposure, a longtime editor of the magazine, and the former executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies.