Fighting for Jobs

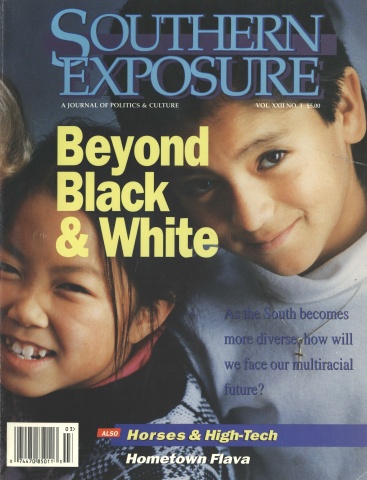

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

As Southern factories close up shop at home and head farther south in search of cheaper labor, they do more than abandon factories and throw people out of work — they devastate entire communities. The Tennessee Industrial Renewal Network of Knoxville is helping to combat the disruption created by the global economy. With a staff of four and support from labor unions, community organizations, and environmental groups, TIRN assists those hardest hit by plant closings. Bob Becker, a TIRN organizer, talked with Southern Exposure about how the group builds consciousness and coalitions.

The Tennessee Industrial Renewal Network was founded because of the continuing deindustrialization in Tennessee. Back in 1988, the Commission on Religion in Appalachia did a study that found that over 25,000 people in the region lost their jobs between 1984 and 1988. Since then, federal figures show that more than 50,000 jobs have been lost in over 400 plant closings and mass layoffs.

In June of 1989, a coalition of workers and activists pulled together 100 people in Chattanooga and brought in some national experts on plant closings and deindustrialization. After the conference folks decided to form an organization to deal with these things, and TIRN was born out of that.

We’re actually a coalition that utilizes the resources of different organizations. We work on three issues: plant closings and job loss, fair trade, and temporary employment.

Say you’re in a community and you think your plant might be closing. You might have gotten a 60-day notice. You might have just heard rumors. You might just be looking around the shop floor and see all the signs — equipment moving out and things running down. What we do first is come in to help people get organized. If there’s a union in the shop, that’s already done. In most cases there isn’t. So the first step is organizing folks so that they can make decisions and communicate.

Then we help assess what can be done. In some situations, there’s not much that can be done — places are going to close. They’re not profitable. The machinery is too old. The product is of bad quality. In those cases, we organize people to take advantage of retraining programs or to provide moral support for each other. A plant closing has been compared to a death in the family, and having a support network is real helpful.

In most cases, however, plants aren’t closing because of lost money or lost market shares. They’re closing because of corporate restructuring, or because the factory is moving for cheaper labor. And in that case, there are lots of low-key options — finding a new owner, new financing, new products, or new management.

Another option is organizing a big pressure campaign to stop the company from doing what it’s doing. That’s what we did at the Acme Boot Company in Clarksville, Tennessee. We tried to keep the company from moving jobs to Puerto Rico just so they could take advantage of a big tax credit.

The Acme Boot campaign started in 1992 through a contact with the union that represented the workers there — the United Rubber Workers. We spent the rest of the year working with the union, talking about the options. If you’ve been working on the shop floor like these people had for 20 or 30 years, you haven’t thought a whole lot about strategies for saving your job.

At the same time we did a couple of rallies protesting the closing. We had one that involved 500 people. Al Gore’s dad, who had been a U.S. Senator back in the ’60s here in Tennessee, came to the rally.

Around the beginning of ’93, we got confirmation that Acme was moving the jobs to Puerto Rico. The campaign then became one of organizing to do something about Acme getting these tax breaks to move jobs overseas.

We held rallies and meetings with congressional people. We got on the CBS and the ABC evening news. Bill Clinton mentioned jobs going overseas for tax breaks in his State of the Union address. That was one of the high points of my life hearing that. So we had good publicity and good action to keep the issue hot. We also filed a lawsuit against Acme, challenging the legality of them getting tax breaks in Puerto Rico.

They still moved there. But as a result of our work and as part of the national campaign, there was some change made in the tax breaks. It’s a lot better than it was.

The publicity also drew another potential owner onto the scene. A Florida businessman worked on a deal with the union for a majority worker ownership plan that would start a new company. He also worked out a plan where Acme was going to buy most of the product of the company for two years on a subcontract basis.

When the potential new owner couldn’t come up with the money he promised by the end of last year, Acme sold the building to another company to use as a warehouse. That took the steam out of everybody’s engine. With the building and the jobs gone, people moved on to other things.

So the effort to reopen the boot factory ended. People didn’t have the energy to try again. Now the American Federation of Labor has sanctioned a boycott against Acme products, and we’re pushing that.

We got involved in fair trade issues not long after the founding conference back in 1989. We started workers’ think tanks, where workers who had lost their jobs in closings could get together and talk about what needed to be done.

People at that time were saying, “The Mexicans took my job.” We dealt with that by bringing some Mexican workers up from the free trade zone. Two of them toured the state, talking about their own working conditions and wages and living conditions.

We followed up by taking eight or nine east Tennessee workers down to the free trade zone in Mexico. Their attitudes changed from “The Mexicans took my job” to “The company moved my job to Mexico to exploit people there.”

Folks got a real good sense of what all this free trade talk is about. It’s about lowering wages and working conditions so corporations can make more money. Folks came back from that tour and did a slide show that they took around to unions and churches and community groups. And they started learning more about the North American Free Trade Agreement.

The worker educational exchange grew into a big campaign for a renegotiated NAFTA. As long as the agreement didn’t include provisions to raise working and living standards in Mexico, all it was going to do was drive down wages here, drive down wages there, drive down living conditions in both places, and allow big corporations to make big profits. We had working people from Canada, Mexico, and the U.S. who did a tour across the state talking about what NAFTA really meant for working conditions and free trade.

We ended up getting sold out completely. In the final blitz to approve NAFTA, Bill Clinton and Al Gore pulled out all the stops and got everybody in the Tennessee delegation except Jim Sasser to vote in favor of it. We were real disappointed. We had gotten promises from several congressmen that they were going to vote against NAFTA. They had obviously lied to us or didn’t really give a hoot about what the people thought. They were going along with the president and the vice president and the business community.

Now we’ve moved on to a monitoring project that tracks the impact NAFTA is having on wages and living conditions in the state. We’re also doing some more education and lobbying, and we have another group of eight workers from Tennessee visiting in the free trade zone for another educational exchange.

Our efforts around temporary workers began with the closing of a warehouse in Morristown. After folks lost their jobs, they went to the unemployment office. They were told, “We don’t have any openings. You need to go over to the temporary agencies in town.”

When they got there, they found factories that were run completely by temporary workers. They found workers who had been temporaries for a couple of years doing the same job as full-time employees — for half the pay and no benefits.

We hooked them up with a group called Save Our Cumberland Mountains and they organized themselves into a group called Citizens Against Temporary Service. We worked together on a statewide legislative campaign to change the laws on temporary workers. We said that you can’t pay workers less just because you call them temps if they’re doing the same work as regular employees. We got beat but we are going to keep trying.

Ultimately rebuilding the economy is going to take some legislative changes — new laws that say it’s not right for a company to do anything it can to cut wages. The idea is to start with local actions. One thing we learned from our last effort is you can’t do some good work in two locations in the state and then go to the legislature. You’ve got to build up a much broader perception of the problem and develop a much broader network.

We start in communities where we have a base, either with unions or community groups, and do some direct action against a factory that is using a lot of temporary workers. We also broaden our base by reaching out to allies and doing education work with churches and civic groups.

TIRN and other organizations like it are working to give citizens power in making decisions about the economy. If people don’t organize around economic issues like plant closings, worker rights, and economic development, the decisions will be made by unelected corporate officials. And the decisions will hurt workers and local communities. Changing the structure of power between citizens and corporations is essential to having good jobs and a strong economy.

Tags

Ron Nixon

Ron Nixon is the former co-editor of Southern Exposure and was a longtime contributor. He later worked as the homeland security correspondent for the New York Times and is now the Vice President, News and Head of Investigations, Enterprise, Partnerships and Grants at the Associated Press.