This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

Her family came to America before she was born in 1914, but Delia Serralles has lived her whole life as a Cuban. Their culture thrived in the Latin quarter of Ybor City in Tampa, Florida, a town turned by their labor into the cigar capital of the world.

A trip to her house is almost like visiting another country. Even after 80 years, Spanish comes more easily to Serralles than English. She translates for her husband, Eduardo, who sits with some friends under the orange trees that shelter cages of lovebirds and parakeets. Chickens and roosters wander around the yard, while the aroma of bread pudding in the oven fills the house.

Serralles worked for 45 years in the brick cigar factories. By the time she was born, some 10,500 workers in more than 100 factories and countless tiny storefront or home-based “buckeye” operations were already producing 250 million hand-rolled cigars a year. Most of the workers were Cubans, with a smattering of Italians. Their employers, the cigar barons, usually were Spanish.

“In those days, hardly anybody spoke English in Ybor City,” Serralles says. Her three children started school knowing only Spanish.

Her family followed the cigar trade as it moved from Cuba to Key West to Tampa. With each move, factory owners sought to leave behind the labor strife that resulted from their efforts to control workers. In this, they were continually frustrated.

Cuban cigarworkers considered themselves craftsmen, not laborers. Each step in the cigarmaking process — selecting tobacco leaves, rolling cigars, banding them, packing them — was a specialty. Serralles started at age 18 as a stripper, one who removed the big vein from each leaf. At their peak, she and her husband could roll a thousand cigars a day, all of uniform size and shape, using nothing to measure with but their hands and eyes.

Cigarmakers in each factory paid 10 cents a week for the services of a reader, who sat perched above the rolling tables and kept them entertained by reading newspapers, novels, or short stories. The most talented could imitate any kind of voice and practically enacted the story.

Readers often selected news articles from union papers published in Ybor City, which were heavy on international politics, socialism, and class conflict. Tampa’s cigarworkers bankrolled Jose Marti’s revolution against Spanish rule in Cuba, donating 10 percent of their salaries each week. Decades later, another Cuban revolutionary came to Tampa seeking support. He and his companions stopped by the Serralles house one time. Delia didn’t know until later that one of the men she served espresso to that day on her front porch was Fidel Castro.

Cigarworkers opposed any change they thought threatened their status as skilled craftspeople, such as measuring out tobacco instead of relying on their own abilities to estimate how much was needed. Strikes were common.

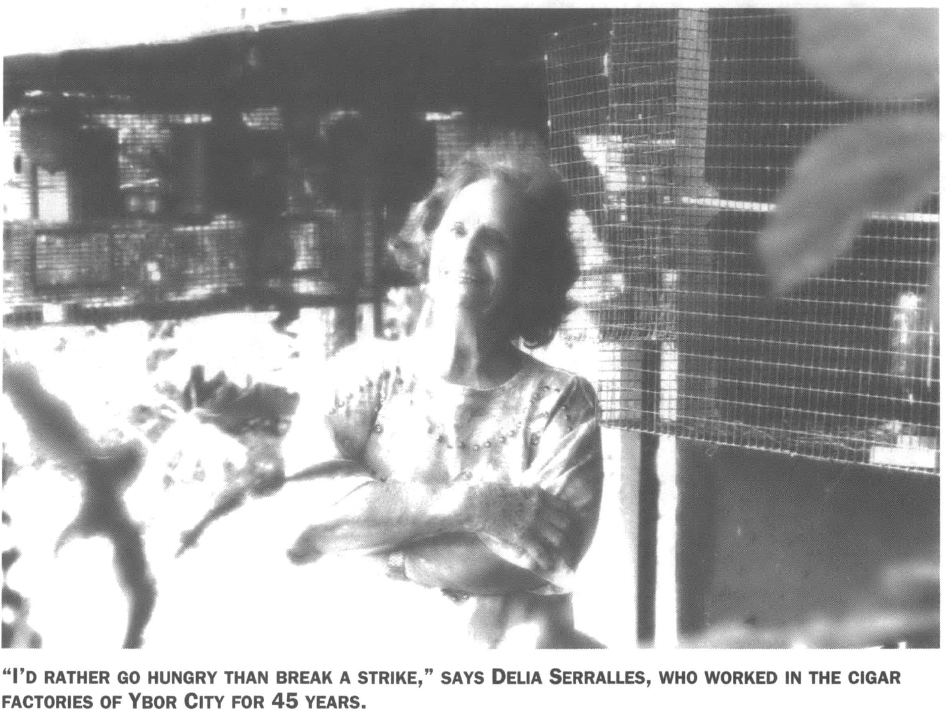

Native-born Southerners viewed the proud, outspoken Cubans as dangerous agitators. They always sided with the factory owners. Serralles remembers watching Tampa police officers escort scabs into the factories. Decades later, her contempt is still evident. “I’d rather go hungry than break a strike,” she says.

She also remembers the .38 pistol her father bought after being threatened by the Ku Klux Klan in Key West. He carried it with him all the time. He ran a grocery where customers could charge their purchases with nothing but their promise to pay weekly.

His wife died at 30, leaving him with five children. They came to Ybor City in 1922 and moved around the neighborhood often, always seeking less expensive quarters. Each time, her father would disinfect their latest abode by burning sulfur candles in it. “He raised five good children,” she says. “Nobody in jail.”

By the time she was 10, Serralles and her sister were doing the housework of grown women. Thursday was laundry day, which meant spending hours scrubbing clothes against a washboard. The wood floors of the house had to be scrubbed every week too, on hands and knees.

On Saturdays, though, she and her friends would promenade up one side of Seventh Avenue and down the other from 14th Street to 19th and back, looking at the boys and stopping by the ice cream store. Her brothers weren’t allowed to bring their friends home unless their father was present. Even as a young woman in her twenties, when she went to a movie with her future husband, they had to take a five-year-old niece along as a chaperone. The niece, Evangeline Alvarez, remembers being slipped a nickel on the way home so she would look the other way while the suitor tried for a goodnight kiss.

“We were all virgins when we married,” says Serralles. “Things are different now.”

She has pictures of herself as a slim, smiling, dark-haired beauty clutching a mariachi while leading a line of costumed rumba dancers at La Verbena, the annual tobacco festival. She was always chosen to lead; she never missed a dance. “I used to be such a good dancer,” she says.

As the cigar trade changed, the fortunes of Ybor City declined. Factories mechanized, moved north, or went out of business as demand for cigars dropped. The sons and daughters of cigarmakers looked elsewhere for work. Eventually, they moved out of Ybor City. The final blow, however, was urban renewal.

Block after block of what had been cigarworkers’ houses was torn down. Some were replaced with public housing projects. But even today, there are vast vacant areas where houses, corner stores, and barbershops once stood.

Serralles moved out of Ybor City in the ’60s when the state purchased her house so it could build an interstate highway through the neighborhood. She got less than $10,000 for the three-bedroom house she’d lived in for 24 years.

She reaches into a cabinet under her kitchen sink and pulls out a coffee pot. She brought it with her from the other house, she says. It’s an old-fashioned drip pot with a sock in it. She won’t use any other kind.