This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

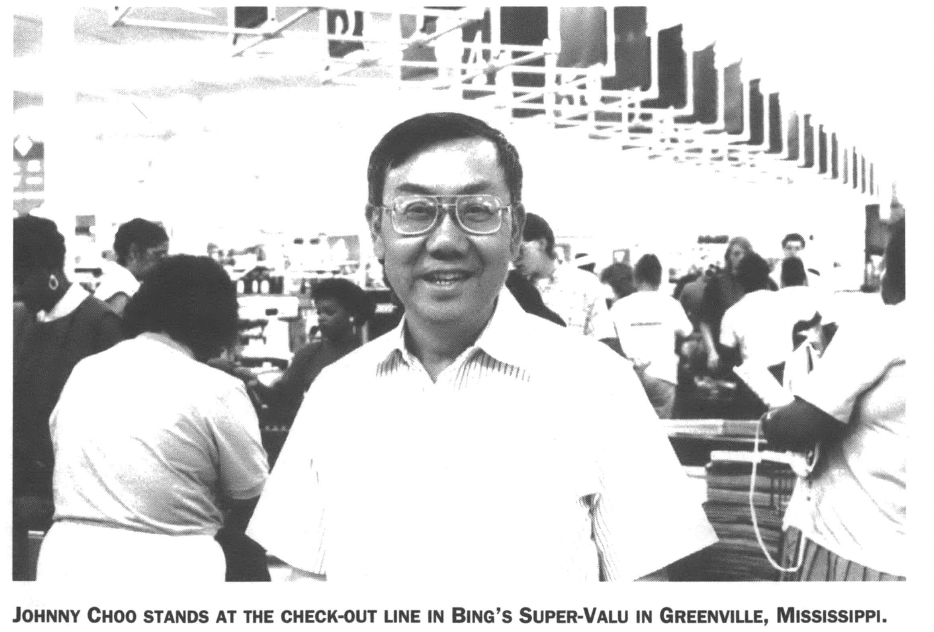

Bing’s Super-Valu faces a busy Highway 1 in Greenville, Mississippi. The wide, flag-draped supermarket sports a modem plexiglass canopy across the front. Although barely midmorning, the parking lot is packed with cars.

“Oh, the parking lot is always crowded,” a bag boy says. “Bing’s has lots of loyal customers. And it’s the best place in town to work.”

Johnny Choo, the owner of Bing’s, greets us at his office, which overlooks the check-out line. The walls are decorated with dozens of red-and-gold Chinese greeting cards, three Chinese calendars, and two large brass fish, which are Chinese symbols of good fortune. Also lining the walls are many plaques and framed citations, which are American symbols of good fortune.

Despite the rush of shoppers and store crew, Choo sits for a moment and talks about his life in Mississippi.

“After I graduated from Mississippi State, I went to California. I was an engineer in the aerospace industry, but I was unsatisfied with my situation. I was making good money for those days, but I was not getting ahead. After I had been there three years, my father called and said he had a 12,000-square-foot store in Greenville. He needed help running it and wanted to know if I would be a partner. I said yes and came home. It is better to be your own boss, of course, and this is where my family is.”

Bing’s Super-Valu is still a family business; Choo’s father-in-law and mother-in-law stock shelves and check out customers. Choo and his family often spend 12 to 16 hours a day at the store, so a room off the office is furnished as a living room. In contrast to the way Americans divide life into segments, the Chinese do not separate life from work.

“My father borrowed money from relatives and traveled from China to the Delta in the 1920s and opened a store. We have many relatives here, from the Canton region of China — that’s the dialect we speak, Cantonese. My father could not speak English at all, so it was hard for him at first.

“But it was hard for all the Chinese. In those days we had a separate hospital, school, and church. Over the years, though, the discrimination against Chinese has decreased. Our families are still very close, but the Chinese identity is less. My wife is from Hong Kong, so we maintain contact with Chinese culture. She serves special foods on holidays and we stay in touch with relatives and friends.

“I do not emphasize Chinese ways all that much. Maybe that is because we are more accepted here, I don’t know. The need to band together is maybe not so strong now, and many Chinese are leaving the Delta. Anyway, my children do not speak the language except for a few words. The children care less about the culture, and they are educated to be like other Americans.”

Just then a Washington County supervisor appears at the door. He shares with Choo the news of fields and roads flooded by recent storms, and explains plans for a meeting with the governor to press for disaster relief. Choo listens intently, then nods and offers whatever assistance is needed from him.

“Just call me,” he says when the two men shake hands. The supervisor excuses himself and rushes to the next stop on his rounds.

“Compared with California, I like being part of what is going on, and I like the slow pace of a small town,” Choo continues. “I like knowing everybody and being able to get things done with a phone call. I guess my most gratifying work has been with the Salvation Army and setting up the scholarship fund at Mississippi State for students from the Delta. I doubt if I could ever have done these things if I had stayed in California.”

Farther up the Mississippi River is Clarksdale, another Delta town where the Chinese have lived for over a century. On a hot August morning, Daniel Shing welcomes us at his grocery store in the heart of the African-American neighborhood.

“My father came to the United States in 1920. The earliest settlers stayed on in the Delta because it is so much like their homeland in climate and living conditions. They could bring over other family members, but only with much hard work. That was the pattern — hard work and bring other family members over. And as far as getting along, well, you might say, ‘They didn’t stir no water nowhere.’ They stayed to themselves.”

Shing was born in Clarksdale, graduated from the University of Mississippi with a degree in business administration, and married an immigrant from Singapore in 1967. He returns to China every few years and brings home Chinese videotapes and seeds for Chinese vegetables and herbs.

Although the newer generation keeps up with tradition, Shing says, “we are more outgoing, too.” Shing himself is on the board of the Clarksdale Chamber of Commerce, the Exchange Club, and the local arts council. The mayor of the nearby Delta town of Shaw is Chinese, and others are also taking an active role in civic life.

Until recently, Shing explains, “there was rarely any outward involvement with the broader community. Nothing public, like a parade or banquet. Then a few years ago the mayor and some other local businessmen persuaded a group of Chinese investors from Taiwan to visit Clarksdale. These investors had to be persuaded because of the state’s reputation for backwardness. So when they came, I met with them, to show that there was an active Chinese community in Clarksdale. I told them that if the Taiwan businessmen have money to invest in the U.S., why not invest it in a Delta town where Chinese live?

“Well, one thing led to another and soon the mayor and I were on our way to Taiwan for more meetings. Not long after that, the state even set up a trade office there. So, to make the story short, the city of Clarksdale asked me to initiate a Chinese New Year’s Party that would be open to the whole city. So I did it. There was a parade and the banquet sold out. But, in spite of all the work, the Taiwan investors decided to go elsewhere with their money. “On the good side, though, the New Year’s celebrations succeeded in bringing more Chinese into the life of the whole community. Now Chinese are more willing to join civic groups.”

I ask about the Chinese vegetable and herb seeds he mentioned earlier, the ones he brings back from China. Somebody must be gardening with them, right?

“Yes, and the best gardener is Kam Chow. If you want to meet him, I’ll take you.”

Kam Chow has retired, but his family continues to run his one-room corner store in a mostly black neighborhood. From the street all you see of Kam Chow’s garden is a chain link fence covered with vines. But when you enter the garden — which is about 20 feet wide and 30 feet long — you are surrounded by a carefully constructed framework. Melon vines cover walls and a roof made of found lumber and garden fencing. Stacks of lumber, boxes, and cement blocks support huge melons, which are marked with numbers.

“So they can be picked in the right order,” Shing explains.

Other canopies support Chinese cucumbers and beans with long pods. Without the overhead vines as a sun screen, the weaker plants simply would be impossible to grow. On the ground, in an open space, there are long, raised beds with Chinese varieties of broccoli and mustard, bok choy, and tomatoes. Some of the flats have just been seeded with crops that will mature in the fall.

Kam Chow has rigged up an ingenious irrigation system with a series of garden hoses to carry runoff from the store’s air conditioner to every part of the garden. He makes fertilizer by piling dead plants and trimmings in the spaces between flats.

“He had his soil tested by the agricultural lab at Mississippi State,” Shing says. “He learned that the soil was too rich, so he had to add some lime. Otherwise, no fertilizer!”

On our way back into the store, I ask Shing if the garden is really as fruitful as it appears to be. “Productive?” Shing smiles. “Kam Chow’s garden keeps his whole family in vegetables all year long. That’s true Chinese gardening.”