This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

Just north of Atlanta in DeKalb County, Georgia lies Census Tract 212.04. The sliver of a neighborhood around the Peachtree Airport contains all the trappings of a working-class suburb — well-kept homes and modest apartments, tree-lined streets and commercial strip malls.

For years, all but a hundred or so of its 1,541 households were white. In 1980, the census showed, Hispanics comprised only five percent of the population, and Asians made up barely three percent.

In a single decade, all that has changed. Today Census Tract 212.04 is one of the most culturally diverse areas in the South. According to the 1990 census, white residents now number in the minority. More than a third of all households are Hispanic, and nearly a fifth are Asian.

The remarkable transformation of this one census tract mirrors the shifting demographics of the rest of metropolitan Atlanta. Over the past 10 years, the city and its suburbs have become home to 4,000 Vietnamese, 10,000 Indians, 25,000 Koreans, 30,000 Chinese, and 100,000 Hispanics.

Rebecca McCarthy of the Atlanta Journal and Constitution summed up the sudden shift shortly after the 1990 census figures were released. “The city that didn’t have a pizza parlor until 1959,” she wrote, “now boasts a Korean Chamber of Commerce, a Hmong church, a Hispanic yellow pages, many Catholic masses in Spanish, a Russian Pentecostal congregation, a Korean radio station, a Hispanic weekly newspaper, a Chinese community center, and Baptist churches for everyone from Romanians to Haitians.”

The increasing racial and ethnic diversity in Census Tract 212.04 and metro Atlanta may also herald the future of much of the South. The region has long been home to peoples of all races and colors, but their numbers have risen dramatically in recent years, far outpacing the growth in white and black communities. Today one in 10 Southerners claims Hispanic origins or a race other than black or white. That’s 7.6 million people — more than the population of any Southern state except Texas and Florida.

But the numbers tell only part of the story. The new wave of settlers — and the rapid pace of change itself— already pose a challenge to a region not known for embracing change. Increasing diversity is forcing Southerners to reexamine virtually every aspect of their lives — from language and land use to education and employment. Even the concept of “race” itself has come under renewed scrutiny, as policymakers consider how to classify people by race in an increasingly interracial world.

In short, as pockets of diversity like Census Tract 212.04 spread, Southerners of all races will find themselves confronting an unexplored region in which whites are one of many minorities. “Some people feel real uncomfortable and worried around other races,” a senior at multiracial Cross Keys High School in DeKalb County told a reporter. “You can’t feel that way around here because we’ve got them all — and no one is in the majority.”

The History

The South has always had one of the most diverse populations in the country; non-whites currently comprise 23 percent of the region, compared to 18 percent of the non-South. The region is home to all but a few dozen of the nation’s 186 counties where minorities constitute a majority. Starr County, at the southernmost tip of Texas, is the least white of all: 97.5 percent of its residents are people of color.

But since colonial times, when European settlers killed and forcibly relocated native inhabitants while importing enslaved laborers from Africa, the racial history of the region has been largely a study in black and white. As Duke University historian Peter Wood has documented, the number of native Southerners fell from 200,000 in 1685 to barely 56,000 by 1790. By contrast, the number of whites soared from 47,000 to more than one million, while the number of blacks climbed from 3,300 to almost 591,000. (See “Recounting the Past,” SE Vol. XVI, No. 2.)

It was around the same time this demographic revolution got underway that European colonists began referring to themselves as “white.” As activist Mab Segrest explains in her Memoirs of a Race Traitor, the new term was created to generate solidarity among settlers of diverse and often hostile ancestry — at the expense of people of color. “White people were ‘invented’ to give Europeans a common identity against Africans,” writes Segrest.

Southern plantation owners, eager to add the children they had by enslaved women to their slave populations, also promoted a system of racial classification known as “the one-drop rule.” As Lawrence Wright reports in The New Yorker, the rule defined as black any person with as little as one drop of “black” blood. Thus, by the time Thomas Jefferson supervised the first census in 1790, the lines of race were clearly — if falsely — drawn. Instead of recognizing traditional differences between cultures, racial classification was devised as a political tool to enforce the gap between the powerful and the powerless.

During the Civil War, immigrants comprised an estimated five percent of the Confederacy, and the category of “whiteness” was expanded to include European newcomers. They proved to be eager recruits. “After the Civil War, immigrants adopt an anti-black point of view also,” says Jason Silverman, a Winthrop University professor who has researched the history of the ethnic South. “They want to stay in the South and they want to be successful.”

Other immigrants were not granted such favored status. Ever since the first enslaved Africans were brought to the South, the regional economy has depended on importing a supply of cheap labor — and on using race to control the immigrant workforce. Chinese laborers were brought to Mississippi a century ago to build railroads and toil as sharecroppers. Italians and other European peasants who were used to replace slaves often died from forced labor and disease. Many Lebanese settlers were forced to live in black neighborhoods and were able to move into other areas only after a generation had passed. “We were treated as blacks,” recalls Thomas Farris of Clarksdale, Mississippi.

Farris spoke to Stephen and D.C. Young, who have traversed Mississippi interviewing and photographing 20 groups of ethnic Southerners. Many migrated to the Gulf Coast and the Delta from New Orleans in search of work and a coastal environment that reminded them of home: from the first Jews who settled in Natchez in the late 1700s, to Slavonians and Acadian French who built the seafood industry in Biloxi at the turn of the century, to recent Vietnamese immigrants who have helped revive it.

“The pattern of ethnic settlement has been consistent throughout the years,” the Youngs write in Ethnic Heritage in Mississippi. “New Orleans has always been a major port of entry for immigrants, so it is natural that they settled along the Mississippi River and the Gulf Coast.”

But wherever ethnic newcomers settled in the South over the past two centuries, they remained few in number. In 1970, the census recorded 257,396 Southerners of races other than black and white — barely half of one percent of the region’s 55 million people.

Today the region stands at a demographic threshold no less revolutionary than the one that transformed the colonial South. Fueled by a high level of immigration, the number of Southerners neither white nor black soared to two million in 1980 and 3.5 million in 1990. In addition, there are now 4.1 million black and white Southerners who consider themselves Hispanic, a category the Census Bureau introduced in 1980 and treats as an “ethnic origin” rather than a separate race.

“Up until about 1960, the non-white population was basically all black,” Greg Spencer, an analyst in the Census Bureau office of population projections, said shortly after the figures were released. “Now, blacks are less than half the minority population nationally. Clearly, the changes are coming.”

The Numbers

Changes are also coming for the census itself, following seven months of congressional hearings last year. The national headcount has been under sharp attack ever since census-takers began knocking on doors in 1989. According to a report by the General Accounting Office, the census missed an estimated 4.7 million people — half of them in the South. The black undercount was the biggest ever, and many people of Hispanic origin were improperly assigned races based on the neighborhoods in which they lived.

What’s more, the GAO warns, “the American public has grown too diverse and dynamic to be accurately counted solely by the traditional ‘headcount’ approach.” Federal officials are now considering modifying the five racial categories used by the census — White, Black, American Indian (including Eskimo and Aleut), Asian or Pacific Islander, and Other — as well as the separate category for Hispanic Origin.

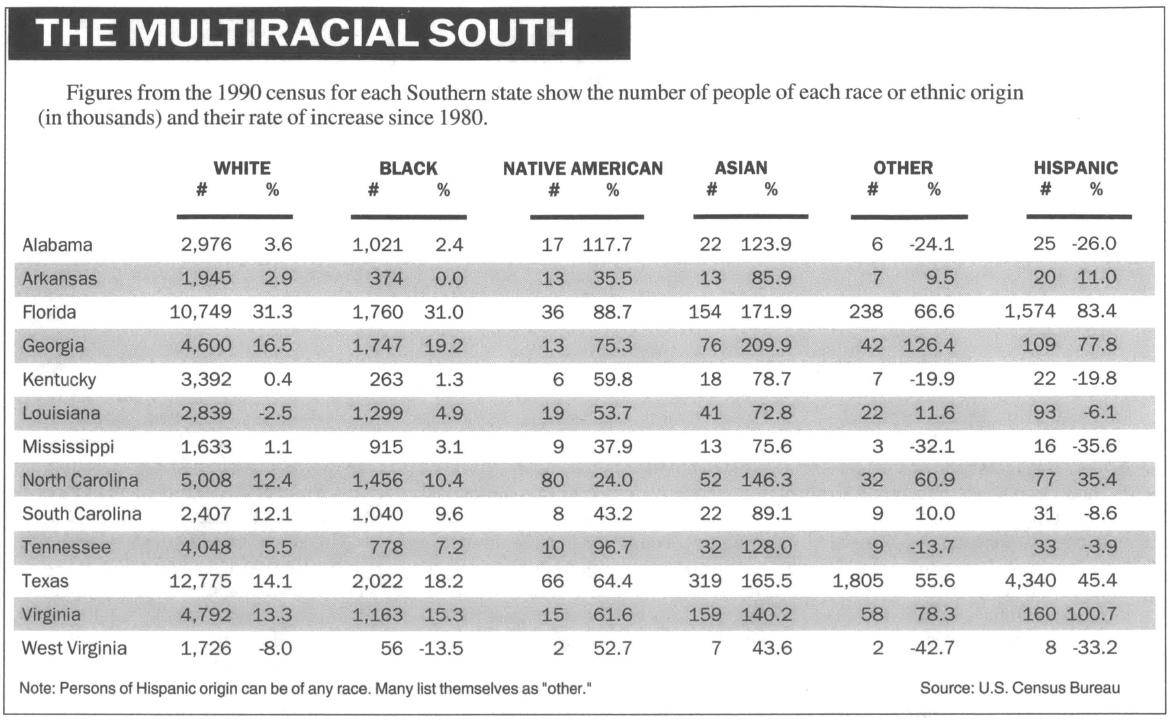

Yet for all its errors and inconsistencies, the census still represents the best way to track racial and other demographic changes. A closer look at the Southern population since 1980 reveals a region undergoing rapid growth and diversification:

▼ The South grew by more than 10 million people during the ’80s — and nearly 2.6 million of the new Southerners were Native American, Asian, Hispanic, or other races besides black and white. During the same decade, 3.3 million newcomers of all races moved to the region from the Northeast and Midwest, giving some cities and suburbs a distinctly “Yankeefied” flavor.

▼ Asians posted the fastest regional growth at 146 percent, followed by Native Americans at 53 percent and Hispanics at 50 percent. By contrast, black and white Southerners increased by just over 12 percent.

▼ The number of Southerners of Hispanic origin — who can be of any race — climbed from 4.3 million to 6.5 million. All but 46,000 of the 2.2 million Southerners listing their race in the “Other” category claimed Hispanic ancestry.

▼ Every group except for blacks and Hispanics grew faster in the South than in the rest of the nation. But the non-South still has a slightly greater concentration of Hispanics and non-black minorities than the South — 13.6 percent versus 10 percent.

▼ The fast-paced growth among Southern communities of color strengthened their presence in the region. Today one of every 200 Southerners is Native American, two are Asian, and 17 are Hispanic.

▼ Despite their growing presence, these “other” Southerners are far from evenly distributed across the region. In fact, their growth mirrors the rest of the South: They increased fastest in the five states with the biggest overall population booms. Nearly 86 percent — all but one million — live in Texas and Florida. Another half million live in Georgia, Virginia, and North Carolina.

▼ Those same states, along with Louisiana, are the only states in the South where minorities other than African Americans comprise more than two percent of the population. The Lone Star and Sunshine states are the most diverse: More than one in four Texans and more than one in seven Floridians is Hispanic or a race other than white or black.

But if Texas and Florida are unusually diverse, demographers say, they are simply precursors of the South — and the America — to come. The Census Bureau projects that by the year 2010, Hispanics will overtake African Americans as the largest minority. By 2020, Florida and Texas will each gain more than two million immigrants, surpassing New York for total population. By mid-century, white Southerners could become another minority.

“It’s a big multicultural change,” Carl Haub of the Population Reference Bureau told the Atlanta Journal and Constitution. “It’s comparable to the changes that occurred due to immigration in the early 20th century, when people came from what were then considered nontraditional countries in Europe. But this is an even bigger change because it involves language and race.”

The Immigrants

The current growth in Southern diversity has been fueled in large part by low birth rates among blacks and whites relative to other races. In addition, legal immigrants made up more than a third of the growth in the 1980s, driving population change more than at any other time since the turn of century. Today 14 percent of all Southerners speak a language other than English at home, up from 11 percent in 1980.

“There’s no region that needs diversity more than the South,” according to Everett Lee, a senior research scientist at the University of Georgia. “The fact that it didn’t attract immigrants held us back intellectually and culturally.”

Farms, factories, and offices in the region also rely on immigrants to fill many low-paying and dangerous jobs that other Southerners are unwilling to perform. The region has increasingly been integrated into the global economy; most newcomers who arrived in the South during the 1980s migrated from the lowest-paying regions in the world — Asia and Latin America.

As with earlier immigrants, many of the newest Southerners started off in coastal and border states like Florida and Texas, then gradually made their way inland to cities like Atlanta, Charlotte, and the Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C. But unlike earlier immigrants, who formed close-knit communities to preserve their culture, many of the newcomers live spread out around big cities, isolated from each other and their neighbors, their cultural and political base diluted by distance.

“Atlanta’s ethnic communities are growing, but you hardly know they’re there,” said Dr. Cedric Suzman of the Southern Center for International Studies. “If we could string them together they could have some impact on the look and feel of Atlanta, but at the moment they’re swallowed up by miles and miles of suburban sprawl.”

Still, in some areas around Atlanta, the newest Southerners are starting to make their presence known. As the Journal and Constitution has reported extensively, one town in DeKalb County near Census Tract 212.04 offers a glimpse of how the face of the South is changing — and how the change presents a challenge to old and new Southerners alike.

For decades, Chamblee was an overwhelmingly white town of blue-collar workers. But that began to change in the 1970s, when immigrants started arriving in the area, attracted by available construction work, good public transportation, and the “refugee discounts” offered by many apartment managers. As word spread and the flow of immigrants increased, the complexion of the community changed. Hispanic residents quadrupled in number, Asians doubled — and more than a third of all whites packed up and moved.

Yet even though whites are no longer a majority in Chamblee, the town’s power structure remains overwhelmingly white. Only one of its 32 police officers speaks Spanish, and none is Asian. All five members of the city council are white men. At one 1992 meeting, city officials joked about setting bear traps to catch day laborers so they could be “sent back to Mexico.” Federal officials had to intervene to calm tensions among Latinos.

Local leaders acknowledge that such tensions are likely to increase as longtime residents feel threatened by the growing diversity. “When you have change and you feel like you’re losing control, that’s no good,” DeKalb County Commissioner Elaine Boyer told reporters.

The Challenges

The issue of control is central to understanding — and overcoming — the tensions sparked by increasing diversity. As the region adds more hues to its racial rainbow, some white Southerners accustomed to having things their own way have responded to their new neighbors with an angry and sometimes frightening backlash. In 1981, Klansmen terrorized Vietnamese families recently arrived to the Texas coast by burning a mock Vietnamese fishing boat in effigy.

Corina Florez, who migrated to Toombs County, Georgia from Mexico in 1983 to work in the onion fields, has also felt the sting of racism. “When I first came to Vidalia, everybody stared when I walked into a restaurant, like they’d never seen somebody like me,” she said. “In a department store, the clerk led me to the cheap sales racks. Sometimes people just assume we’re illiterate, we can’t speak English, we can’t think.”

Much of the reaction involves fights over limited resources. As Southerners more closely resemble the rest of the world, some cities and counties already strapped for cash are being pressed to provide English classes for immigrants, translators in municipal courts, and health services for impoverished newcomers. Not far from Chamblee in the town of Doraville, for example, officials fought a recent redevelopment project designed to provide affordable housing for immigrants.

“Why would we want to attract more immigrants?” Vice Mayor Lamar Lang told the Journal and Constitution. “We got plenty. We got enough to go around. If you want any in your neighborhood, we’ll send you some.”

But hostility and discrimination by whites is only the most immediate reaction to diversity. As the white majority dwindles and a multitude of other races find themselves vying for limited resources, the region is experiencing increasing tension among minority groups.

“The tensions are really among the poor people: blacks, Asians, and Hispanics,” says Xuan Nguzen-Sutter, a native of Vietnam who directs refugee programs for Save the Children in Atlanta. “I’m trying to get kids into Head Start programs, into all the services that are available for low-income people, and we do get a lot of reluctance. The midlevel managers feel like the program is more for African Americans. They feel we are taking spots that should be reserved for African-American children.”

Interracial tensions arise in part from widespread economic disparity among similar groups. According to a 1992 report from the Census Bureau, some immigrants arrive with little capital, while others have money to get started. “Some Asian groups, such as the Chinese and Japanese, have been in this country for several generations,” the report notes. “Others, such as Hmong, Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians, are comparatively recent immigrants.”

In other words, people classified as members of the same race by the Census Bureau are often as different from one another as they are from members of other races. “Asian” covers people of dozens of nationalities, languages, and cultures, some of whom view each other as traditional enemies. “American Indian” includes every native inhabitant from Eskimos in Alaska to Seminoles in Florida, while “Black” groups together Spanish-speaking Cubans, French-speaking Haitians, and Portuguese-speaking Brazilians. Even “White,” a category created and expanded to foster racial solidarity among Europeans, includes groups as disparate as Welsh, Germans, French, Scandinavians, Russians, Scots, Poles, and Slavs.

What’s more, the census has no category to acknowledge children of interracial couples — a significant omission, particularly in a region like the South where black, red, and white have been intermingling for more than three centuries. Since 1970, the census reports, the number of interracial couples has jumped from 310,000 to 1.2 million. By contrast, same-race couples have increased by only 16 percent.

In recent years, multiracial citizens have launched a new movement to enable people to identify with the totality of their heritage. In the affluent suburb of Cary, North Carolina, an interracial couple refused to enroll their child in elementary school in September until officials agreed to classify him as Multiracial. In Atlanta, a magazine called Interrace founded in 1989 for interracial couples now boasts 25,000 subscribers.

“Before the civil rights movement, the whole effort was to pass as whites,” Carlos Fernandez, president of the Association of MultiEthnic Americans, told American Demographics. “Now we’re seeing the opposite — people wanting to identify the other way. Mixed-race people who once would have let themselves be considered white are insisting they’re black.”

The same appears to be true for Native Americans, whose ranks in the South swelled by more than half during the 1980s. In fact, ethnic pride may account for part of the increase among Indians, many of whom previously identified themselves as white.

“Native Americans can include anybody,” says Eddie Tullis of the Poarch band of Creek Indians in Alabama, where the census showed that Indians more than doubled during the ’80s. “If you trace your ancestry back four or five generations, you’ll find some Indian ancestry. It’s popular to be an Indian now.”

The current racial categories used in the census were created in 1978 when the federal Office of Management and Budget adopted Statistical Directive 15 to help federal and state agencies collect and share uniform data to better enforce the Voting Rights Act, equal employment laws, and affirmative action plans. In July, responding to growing dissatisfaction with the categories, the OMB began hearings to consider a variety of changes: adding a Multiracial category, changing “Black” to “African American” and “American Indian and Alaskan Native” to “Native American,” including Hispanic as a racial group instead of a separate ethnic category, and adding a new group for Middle Easterners, currently classified as White.

Some policymakers and grassroots organizers worry, however, that diluting categories and allowing people to self-identify their race could undermine enforcement of civil rights laws designed to protect the very people who find the categories offensive. “The programs set up by the government to make sure minorities are treated fairly would take a huge hit,” Katherine Waldman, statistics supervisor for the OMB, told the Raleigh News and Observer. “How would affirmative action work? How could we enforce anti-discrimination laws if we couldn’t look at the records of a workplace and be able to tell there are no minorities working there?”

At the heart of the policy debate is the very concept of “race” itself. Counting and grouping people by racial categories helps us fight discrimination — but does it also perpetuate racism by institutionalizing false racial distinctions? Can we preserve “race” as a useful statistical device and yet find ways to acknowledge that such measurements can never truly reflect our rich diversity as a people?

Such questions will become more pressing as the racial and ethnic composition of the South continues to change — as the region becomes, in the words of the DeKalb County high school senior, a place where “no one is in the majority.” Southerners other than black and white may currently represent only a tenth of the region’s population, but their influence is already shaping the South of the 21st century.

“Absolute numbers alone do not indicate impact,” says Everett Lee of the University of Georgia. “It’s a question of visibility and roles played. Just go out to the universities and look at the students. That’s where you’ll see the impact — and it will get larger and larger as time goes on.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.