This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 3, "Beyond Black and White." Find more from that issue here.

Seetha Srinivasan, a senior editor with the University of Mississippi Press, greets us at her office in Jackson. Like other Indian immigrant women, she wears the traditional silk sari. I ask whether maintaining Indian customs presents any problems for her.

“Oh, yes, it has been difficult,” she answers, “but it is becoming easier and easier to have all you need to live the Indian way in Mississippi. Peddlers come from Nashville and set up shop in a motel. They sell spices and clothes — even vegetables and fruit. Indeed, the Indian community is beginning to have a presence.”

Srinivasan recalls what it was like when she and her husband settled in Mississippi in 1969 from Berkeley, California. “In those days there were only eight or 10 families in Jackson. Now there are 200 plus. The membership in the Indian Association lists 345 names statewide, but there are many, many more. The Indians who came here in the ’50s and ’60s were professionals, but now whole families are coming and they are people of all occupations. We have many people from several towns in India, and we have many from East Africa by way of England.”

Srinivasan laughs when I ask why many Indians in Mississippi operate motels. “Well, you do know about the motels! But there are Indians in every profession and all types of businesses — gas stations, dry cleaners, ice cream parlors, you name it. And you will find that Indians try to employ other Indians, so that Indians will have jobs and not be forced into taking public assistance.”

What about the persistence of Indian culture?

“This is very important for us. We now have the Hindu Temple in Brandon, which was built under very difficult circumstances. Our community is not a large one, but we believe that the temple is a way to keep alive the traditions, to serve as a focal point for the group, and to be there for the children.

“Hindu religious practice, by the way, is more relaxed about things like attendance at temple events. Much of our religious life centers on the home, but we go to services more often here for social reasons. And the children go. They should have some roots, because they have a dual heritage. Their children will be even more American, I’m sure, but the roots will be there for them.

“The ties to India itself, especially among the older generation, are still strong. People follow the politics and social changes. They travel back whenever they can, and bring parents for visits. There are also professional ties, such as the scientist at the University Medical Center who goes to India for a three-month residency. Some doctors even own shares in Indian hospitals. For the younger generation, however, the ties are less strong.”

What has it been like for Indians in Mississippi? Have there been any bad experiences because of race or religion?

“Fortunately, Indians in large towns have never experienced hostility or discrimination. In fact, we have been made to feel welcome. People always are asking me, ‘Do you like it here?’”

Srinivasan smiles. “Maybe discrimination will come when we’ve been here long enough to be a threat. Maybe. But for now it’s okay. The children feel fine in the schools, and that’s wonderful.”

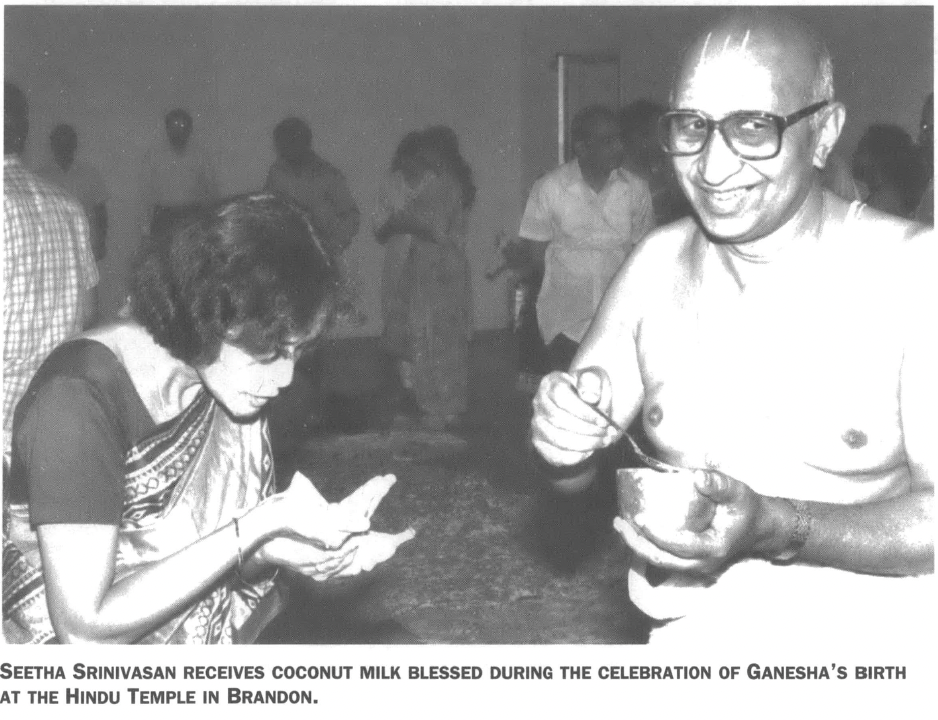

As it happens, the Hindu Temple is soon to have what may be the most popular celebration of the year, the birthday of Ganesha. Srinivasan invites us to attend as her guests.

One September day a few weeks later we arrive at the Hindu Temple, a long, low white building with no exterior decoration placed neatly in a grove of pine and oak trees. Srinivasan meets us at the door, where we remove our shoes. The service is already in progress.

“Are we late?” I ask.

“Certainly not. The service goes on for quite a while. Remember what I said about our relaxed way? People are free to come and go. The important thing is that the ceremony is performed and that we participate in some way.”

Inside the temple a long room opens into other, smaller rooms along the wall opposite the entrance. Srinivasan explains that each stall contains the idol of a god.

“Or will contain, when the Temple Society can raise the money. Ganesha is so popular that his was one of the first we bought. Our Krishna will be delivered one day soon.”

Ganesha, an idol of an elephant-headed boy, represents the “Lord of Ganas.” Ganas are the hosts or forces which create obstacles, so prayers are made to Ganesha to remove barriers to any undertaking. The young, who want to do well in their studies, pray to Ganesha.

At the far end of the row of stalls a group of people, women and children mostly, sits on the floor. Everyone faces the narrow entrance to Ganesha’s room where the priest, a slender man in white robes, cleans the stone idol. A few people chant along with the priest’s assistant, but most only watch. Across the room seated and standing men talk quietly.

Srinivasan introduces us to her friends and we chat while the priest gives Ganesha a rubdown with bananas, oranges, and flower petals. After a while, the priest blesses a cup of coconut milk and passes it among the celebrants. Each person cups their hands, takes a dribble of the milk, and drinks it.

After the ceremony, the congregation enjoys a light dinner in the temple kitchen. This fellowship hour, Srinivasan explains, is a principal reason for having the temple.

“People have driven here from all over the state for this,” she says. “What better place to be on Ganesha’s birthday?”