This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

Summerton, S.C. — LaTasha Henry is only 17, yet she’s already thinking about future generations. When she graduates from Scotts Branch High School next spring, LaTasha plans to go to college, then return home to teach.

Education runs in the family. Her mother works for state educational television in Columbia. Her grandmother, a teacher’s aide, instilled LaTasha with a love of learning. And her great-grandfather, Gilbert Henry, helped launch the landmark case Brown v. Board o fEducation that abolished school segregation.

That legacy inspired LaTasha to be a teacher. “It just seemed like the right thing to do,” she says. “I realized it was very important.” She hopes to earn her way to Duke or some other good university on a scholarship.

It’s a big dream for a kid from Summerton. Students in Clarendon County District One rank at the bottom statewide on almost every measure of academic performance. Rampant poverty is one factor. About 95 percent of the student body qualifies for free or reduced-price lunch, a level twice the state average.

Summerton schools are also among the least integrated in the nation — all but 26 of the 1,300 students in the district are black. Last year, only two white students out of 568 went to LaTasha’s school in grades seven through twelve.

Segregated schools spurred black parents to fight for equal education for their children more than 40 years ago. Back then, white children rode buses to brick schools with indoor plumbing. Black children walked miles to ramshackle shanties with outdoor privies. In 1949, Clarendon County spent $179 on each of its 2,375 white students but only $43 on each black student.

Gilbert Henry was one of 20 black parents to sign a petition courageously seeking equal facilities. Harry Briggs, the first to sign, lost his job at a gas station. Others were fired, denied credit, burned out, or fired upon. The Reverend J.A. DeLaine, an inspired A.M.E. minister and organizer, fled the state after he shot back.

“The people of Summerton — particularly the whites — were just stunned that the people who put their names on that petition stood their ground,” says James Washington, head of the Clarendon County branch of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People.

When the white school board refused the petition, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP argued the case of Briggs v. Elliott all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court — and won. Combining the Summerton case with four other lawsuits under the heading Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, the high court unanimously struck down school segregation in South Carolina and 16 other states that still practiced it.

But little changed in Summerton. Eleven years would pass before the first black student entered a formerly white school. White parents blocked efforts to integrate, offering students the “freedom of choice” to pick the school they wanted. Twenty-eight blacks enrolled in formerly white schools, but no whites went to all-black ones.

In 1969, when the courts abolished the “choice” plan and ordered Summerton schools to integrate, white parents responded by sending their sons and daughters to private academies or schools in other districts with fewer black students. “It was just like they abandoned their family,” says James Washington.

Like many who grew up in Summerton, LaTasha Henry doesn’t consider whites who refuse to attend school with her racist. It’s more tradition, she says, and “stubbornness.”

Outside the schools, whites and blacks in Summerton walk the same streets, shop the same stores and, occasionally, eat at the same restaurants. But their children grow up virtual strangers.

Asked how many friends she has who are white, LaTasha Henry answers plainly, “None.”

Ballots and Bonds

In the four decades since Brown, Summerton has grown accustomed to being put under the media microscope every so often. At regular intervals, reporters from large newspapers or national magazines pass through to record how segregation hangs on in an isolated, Deep South community. Many flocked to the town two years ago after Carl Rowan, here to research a book on Thurgood Marshall, wrote that, “Not a damn thing has changed.”

The outright harassment of earlier years is gone. Summerton now has a black police chief. But on the whole, things remain as Rowan said, with the status quo holding fast.

“The younger generation wants it to change,” says Washington of the NAACP. “But you’ve got some diehards who are willing to let the place die rather than change. When it comes right down to real issues, it’s still, ‘I’ve got mine and you’ve got yours.’”

Lately, however, blacks are showing renewed interest in challenging the white power structure for a share of community leadership. A poor black area west of Summerton launched a drive for town annexation. A black minister ran for mayor. And the NAACP is pressing for redistricting that would increase black representation on town council.

Although Summerton is 54 percent black, only one black has ever sat on the council. The current council is all white. Summerton schools are also pushing ahead. Scotts Branch High School has joined a state project which encourages teachers to experiment with creative approaches to education. In one move, the school will schedule classes in two-hour blocks next year to give teachers and students more time for one-on-one instruction.

Perhaps most important for students and the community is the opening this fall of the new Scotts Branch High School — the first school built in the district since Brown. Whites and blacks worked together to pass an $11 million bond referendum to build the new school and renovate its dilapidated predecessor into an elementary school.

Still, the effects of segregation linger. Under a 1984 law, the state was forced to step into the district this year to try to reverse the poor performance of students. The intervention, the second in eight years, means the district will receive additional funding and consultation from the state education department for three years. Barbara Neilsen, the state school superintendent, says Summerton “has my full attention.”

Despite such assistance, no one is sure if Summerton is ready to move beyond the racial legacy of its past and come together as one community with a shared interest in its future.

“There are some people here who look beyond and see what tomorrow can bring,” said the Reverend Malachi Duncan, the black minister who ran for mayor. “We just don’t have enough of them.”

A Class Act

If you want to improve education in Summerton, says Alice Doctor-Wearing, don’t focus on segregation. Focus on poverty.

“If you come from a home that’s impoverished and parents don’t know what education means, they can’t express that to their children,” she says. “There are just a lot of problems in these poor communities. When I drive around, I see kids whose parents are involved in drugs and alcohol."

Five years ago, Doctor-Wearing quit her job in Washington, D.C. and returned home to help revive Summerton. She started the Scotts Branch ’76 Foundation, named for her high school class, to find ways to combat poverty and improve education.

The grassroots organization works with the poor every day. People drop in to its offices in a converted tavern in West Summerton for help with housing, loans, and job applications.

“People come in and out of here all the time,’’ says Doctor-Waring, sitting at a large desk in her office. “No one else was providing these services. Since we started, people are more motivated to find out what grants and programs are available. These questions would never have been asked before.”

The foundation has a bi-racial advisory board and works on community projects that benefit blacks and whites alike. The group has staged youth plays with anti-drug themes, planted a “victory garden” along Main Street, and sponsored Summerton’s first African-American festival.

“There was a need for me and this organization to be here,” Doctor-Wearing says. “And I feel that we have made a difference.”

Working at the grassroots has made Doctor-Wearing wary of traditional approaches to community problems. She was recently named to a revitalization task force trying to attract jobs to Summerton, but she doubts that it will make a difference.

“It’s the same people saying pretty much the same thing all the time,” she says. “A lot of times we talk about people who need help the most, but those people aren’t at the table.”

Doctor-Wearing views her organization as an alternative to traditional black groups like the NAACP. “The so-called leaders we have in the community haven’t helped anyone,” she says. “They haven’t done anything in 40 years since Briggs.”

Both the foundation and the NAACP have announced plans to build cultural centers in Summerton that would honor the history of the 1954 school desegregation lawsuit and provide badly needed recreational facilities. Summerton has no theater, bowling alley, or library.

Doctor-Wearing is also skeptical of how much the new Scotts Branch High School will improve education, which she sees as the key to improving life in Summerton. “If the kids could be educated, everything else would fall into place. You wouldn’t have to worry about economic development, because that would come.”

But in the end, she says, it doesn’t matter whether the new school helps integrate Summerton schools. “If we can’t integrate, fine. I’m not all about integration. All I'm worried about is self-esteem.”

— J.M.

Clean Streets

Summerton — population 975 — lies at the southern end of Clarendon County, midway between Charleston and Columbia, the state capital. The drive is one hour in either direction.

Wealthy white planters settled the “Summer Town” in the last century. But it was blacks who created the fields of high cotton out of swampland, who chopped and picked it. Today the only large industry in town is Federal Mogul, which makes gaskets. The last two cotton gins were torn down earlier this year, marking the end of King Cotton’s reign in Summerton.

When Interstate 95 opened in the early 1970s, diverting tourist traffic from the town, many of Summerton’s hotels were forced to close. Attracting new business is vital because property taxes shot up 70 percent to pay for the new high school.

Prospects are limited. Summerton has little water and sewer capacity and a workforce that’s untrained for high-tech jobs. The area tries to sell itself to light industries and to use nearby Lake Marion to attract tourists and retirees. A new citizen revitalization task force is studying new economic strategies, and leaders are seeking designation — and special tax credits — as a federal enterprise zone.

“Short streets, long memories,” says a new brochure designed to attract residents to Summerton with visions of “lovely old homes . . . peaceful streets . . . canopies of dogwoods and bursts of azaleas.” For history, visitors are directed to tour a working grist mill and the Richardson graveyard, where six South Carolina governors were laid to rest.

There are some glaring omissions, though. The state-funded brochure makes no mention of the historic desegregation case, the only one from the Deep South that was part of Brown. In addition, the brochure pictures no black residents at all.

Summerton’s black neighborhoods aren’t likely to show up in a tourist brochure. Some of their “short streets” are little more than rutted dirt alleyways. Hurricane Hugo destroyed many rickety homes, forcing residents into trailer homes squeezed onto lots beside shotgun houses.

The division between white and black in Summerton stretches beyond housing. Two-thirds of black residents live below the poverty line, compared to only six percent of whites.

Many of the poorest blacks live beyond the town limits in unincorporated West Summerton, an area Reverend Duncan describes as “a depressed neighborhood where a bunch of people who have lost hope in their lives live day-to-day, falling into drugs and alcohol.”

West Summerton tried to become part of Summerton last year. But the council rejected its annexation request, saying the added property tax revenues wouldn’t cover the extra service costs.

Duncan maintains that the council rejected West Summerton because it would make the town 70 percent black and shift the balance of power from white hands. “Until we get annexation, we can’t make a change,” he says.

Mayor Charles Allen Ridgeway insists that the annexation bid is still pending. “We didn’t vote it down,” he says. “We just tabled it until we could afford it.” Besides, he adds, “They got all the services that in-town has got, they just don’t have the tax bills.” He dismisses those seeking annexation as “just the same people wanting political power.”

Duncan is minister at Liberty Hill African Methodist Episcopal Church, where the original Briggs petitioners met to plan their strategy against the school board 45 years ago. On Sunday mornings, visiting whites are given a place of honor near the front of the church to hear Duncan preach on the need to “walk through the door of opportunity” that Christ provides.

Duncan’s decision to challenge Ridgeway for mayor in the March election marked the first time a black had sought the office. In his campaign, Duncan talked about unifying the community. Ridgeway focused on his record of “cleaning up Summerton,” saying he had used his own money and equipment to clear several overgrown lots and remove litter from the streets.

“There isn’t anyone who wouldn’t admit that it is cleaner here than it was three years ago,” the mayor campaigned.

Though Duncan lost by about 100 votes, he claimed moral victory in having brought more than 170 blacks to the polls, though not all gave him their vote.

Blunt-spoken and impatient for change, Duncan wanted to boycott Summerton businesses last year after a black woman said the town’s white pharmacist roughly tossed her out of his shop. Washington and the NAACP refused to go along, calling the plan unnecessarily divisive.

Duncan viewed the refusal as another example of traditional black leadership falling in step with the white power structure. “All the fault is not the white folks’ fault,” he said after his electoral defeat. “I’m honest. There’s some black folks, too, that believe that whites are supposed to be the leaders.”

Mayor Ridgeway says the fact that he received black support indicates how well blacks and whites get along in Summerton. “I think we’re doing fine,” he says, taking a break from grading a new baseball field for the almost exclusively black Taw Caw Little League. “Now, you get some outsiders come in and cause trouble, but we get along.

“Local people, we need one another,” he adds. “People that grew up here together — black and white — get along real good.”

White Flight

Not everyone feels so optimistic. After six years of trying to turn the school district around, Summerton Superintendent Milt Marley is resigning.

Marley worked in school desegregation programs during the 1970s and served as assistant school superintendent in Columbia. Whatever high hopes he once nurtured, though, are now thoroughly grounded in the reality of the schools and community he inherited.

Summerton schools have been immersed in chaos for years. Both of Marley’s predecessors were fired, one over allegations of financial mismanagement. Marley has put the district on better financial footing, adding $87,000 in grants to its $5 million budget last year. But state budget cuts in the middle of the school year forced Marley to lay off his grant writer along with four teachers, two teacher aides, and a secretary.

“You’ve got to do magic,” he says.

The district manages to keep per pupil spending at about the state average, but the state only covers about half the cost of employee fringe benefits and pays nothing for construction or building maintenance. “That’s why over 40 districts are suing the state over equity,” Marley says.

Summerton has a hard time attracting and keeping teachers. The district hasn’t had a student-teacher in five years. Only 25 percent of its teachers have master’s degrees, compared to a state average of 42 percent. Annual pay is about $3,000 below the state average, but Marley doesn’t believe that’s a major factor.

More often, he says, teachers just don’t want to live in Summerton. Many drive in from larger towns. When they get a year or two of experience, they leave for jobs in less-troubled districts, usually in urban areas. “Basically, rural districts are training institutes for new teachers,” Marley says.

Marley lives in the district, but none of the three school principals does.

The faculty’s lack of training, experience, and knowledge of the community doesn’t help when it comes to understanding and addressing the problems of Summerton’s overwhelming population of disadvantaged students.

The schools themselves are dilapidated. At the old Scotts Branch High School, students don’t have enough equipment for a class to work on a project together, or any lockers to keep their books and coats in. The roof leaks, some classrooms are without heat, and the basketball team shares its locker with visiting squads and fans who need to use the restroom.

The problems extend beyond the school walls. Poor and poorly educated, most Summerton parents are ill-equipped to help their children learn. Blacks 25 or older are half as likely as white parents to have a high school diploma. A college degree is even rarer. Of the 85 people in Summerton recorded during the last census as having four-year college degrees, only five were black.

Above all, Marley is resigned to the fact that little can be done to entice white parents to send their children to Summerton public schools. “White parents feel pressure — social pressure — not to send their children here,” he says. “And it comes not only from the parents but the grandparents.”

According to Marley, the prevailing attitude among white parents is, “I don’t want my children to be the only ones.”

As a result, whites have almost completely abandoned the Summerton schools. Rough estimates based on census and school enrollment figures suggest there may be only 50 to 200 white, school-age children living in the district. Even if they all returned to the public schools, whites would still account for only 16 percent of total enrollment.

Marley, who is white, says the white flight has hurt the three public schools in Summerton. “For any successful school system, you need a broad array of support, and there has been no tradition of that since the whites abandoned the school system.”

Buses and Mercedes

The private school that most white children in Summerton attend is Clarendon Hall, a non-denominational Christian academy founded in 1965. Although it was established at the height of the battle to integrate the public schools, officials insist that the religious academy was created in response to the 1963 Supreme Court ruling that prohibited prayer in public schools.

The school, grades kindergarten through 12, has about 250 students. All are white but for five East Indian children. Miles Elliott, the 31-year-old headmaster, says the school does not discriminate.

According to Elliott, no black child has ever sought admission to Clarendon Hall. Tuition runs about $1,600, with additional fees for registration and building maintenance.

Elliott insists that his students have no difficulty getting along with blacks even though they don’t attend the same schools. “We don’t teach racism here. We don’t teach hate here. None of those things are taught. The children here are very comfortable to move onto situations that are different from here.”

The school program is basic. No art, no computers, and no instruction for handicapped or learning-disabled children. Elliott describes his student body as “average to above average in ability, about 90 percent middle class.”

The school was built for $215,000, with residents donating much of the materials and labor. Elliott says the community still supports the school and appreciates the “strong Christian foundation” of its curriculum.

Elliott, a Clarendon Hall graduate, is the great-grandson of R.W. Elliott, chairman of the Summerton school board when Harry Briggs and other black parents sued. But he says he doesn’t know much more than the general outline of the case. He also dislikes discussing Summerton’s public schools or the attention Clarendon Hall receives for having no black students.

“We rock along smoothly out here, yet we find ourselves on the defensive a lot, which we despise.” Elliott says his only interest is the students — “not to satisfy the people from The New York Times or the Washington Post who come down here and take pictures of our bus next to a Mercedes.”

Teaching Hate

What difference does it make to black students that whites won’t go to school with them?

“It’s kind of hard to explain,” says Ken Mance, the Scotts Branch principal, who is black. “Almost all of them go through an adjustment period dealing with whites. I even notice the way they treat white teachers here. They have a little attitude toward them.”

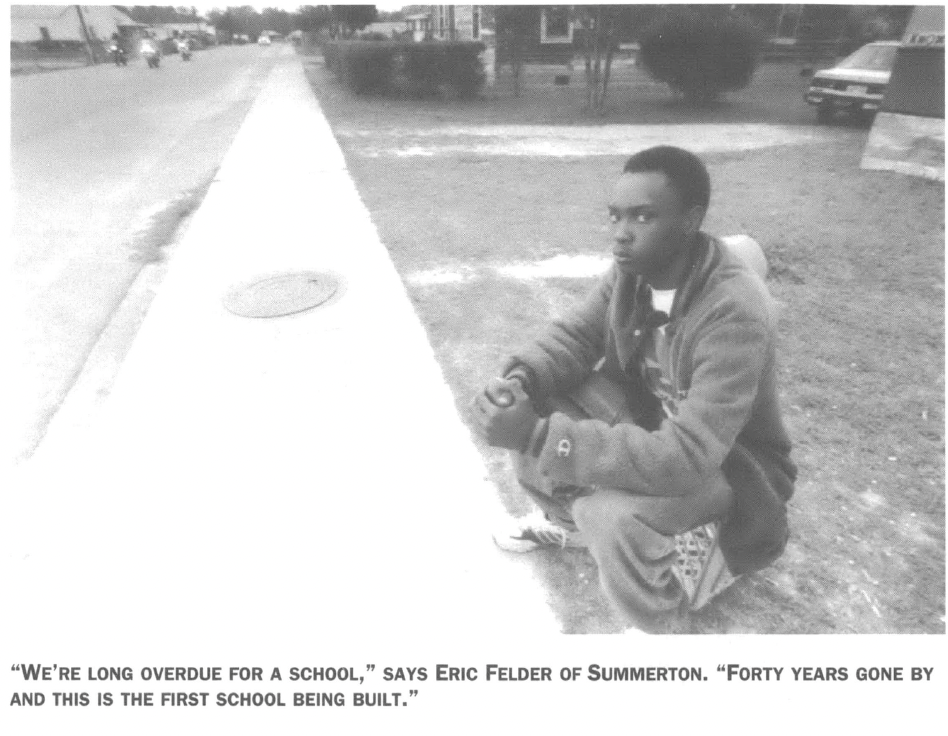

You can hear that anger in the voice of Eric Felder, a 15-year-old student who left New York City to live with relatives in Summerton. He sits on a milk crate watching a pick-up basketball game across the street at Wausau Park. The park also has a baseball field, but the jungle gym has been torn out and the sand in the sandbox was just dumped there in a great heap.

“This ain’t nothing but a slum down here,” Felder says. “There’s no jobs. It’s no wonder somebody’s son is out selling drugs. What do little kids got to play with? Nothing. Nothing ever gets done too much down here.

“We’re long overdue for a school. ’Bout time they got it built. Forty years gone by and this is the first school being built out there and the white people still won’t go,” Felder adds, casting a long glance down the pot-holed street.

“The only time things get done is when you speak up on something. If you don’t speak up, nothing happens.”

James Washington of the NAACP says segregation hurts white children, too. “It instills in these children that integration is not for blacks and whites. That’s what instills the hate. That’s what Summerton is teaching.”

The sharp racial divisions in Summerton are not unique. John Dornan of the North Carolina Public School Forum studied rural at-risk districts in Mississippi and Georgia for a regional research group called SERVE. Like Summerton, the districts were exclusively black, with whites attending private academies.

“By and large, people see schools as theirs and ours,” Dornan says. “One of the things I was shocked by was that it had been like that for so long. It seemed hard for people to imagine anything other than the separation of black and white.”

Dornan notes that such districts almost always post the lowest scores on state-mandated standardized tests. In Summerton, four out of five eighth graders scored below average on a recent test, and less than half of all 10th graders passed the state exit exam required for graduation.

But Dornan emphasizes that improving classroom performance requires a community-wide effort. “If we really want to address the problem of low performance, you’re going to need a team approach that goes beyond the walls of the school,” he says.

In the communities Dornan studied, strong local leadership produced better schools. In one district, a local black official complained that white businesses weren’t involved in the schools — but admitted that he had never sought their help. By contrast, a military retiree in another district galvanized the mostly white chamber of commerce to rally behind the schools, on the grounds that the economic survival of the community depended on it.

Summerton’s economic health is also tied to its schools — and everyone involved agrees that improving them will take the sustained support of the entire community. “The economy is driving things now,” says Barbara Neilsen, South Carolina school superintendent. “Those communities are going to die if something’s not done. They have got to address this problem together.”

Computers and Satellites

The two other public school systems in Clarendon County outside of Summerton don’t share their neighbor’s problems.

Turbeville, at the far end of the county, is about the same size as Summerton. But the three schools in the district have a white enrollment of 56 percent and offer a diverse range of class choices and special programs. The elementary school is the only public school in South Carolina with a Montessori kindergarten. Students at the middle school can learn in a $90,000 computer lab. Last year, every 10th grader at East Clarendon High School passed the graduation exit exam.

Manning, the county seat, has its own school system even though it’s just 10 miles from Summerton. Its schools have a 65 percent black majority. Unlike Summerton, however, whites stuck with the public schools through integration.

Sylvia Weinberg, the Manning superintendent, credits local leaders such as State Senator John Land and his wife Marie for putting their children in the public schools and convincing other white families to do the same.

Land acknowledges that Manning whites didn’t abandon their schools in part because they have a higher percentage of white students than Summerton. “We had a better mix,” he says.

Manning also has fewer people struggling with poverty and more of a tax base than Summerton. The district recently burned the mortgage on its 12-year-old high school, which looks about as good as when it was dedicated.

Manning is just as far from major colleges as Summerton, but it doesn’t feel that way. Teachers have earned master’s degrees from the University of South Carolina, which brought the courses to them. A similar partnership enabled teacher aides to earn credits from South Carolina State University in Orangeburg.

The district has also worked to keep students from feeling isolated. At Manning High, they can let their imaginations soar in Air Force ROTC or take Japanese over a satellite feed from a teacher in Nebraska.

“We think it’s one of the best,” Weinberg says of the high school. “Our top honors graduate last year went on a full scholarship to Princeton University.”

The Dreaded Word

Despite such academic achievements, the other districts in Clarendon County aren’t without their racial divisions. In May, a week before the anniversary of the Brown decision, nearly 100 black citizens in Turbeville marched on school headquarters to protest what they consider disproportionately harsh punishments meted out to black students accused of using alcohol and drugs.

“This is part of a broader problem,” says the Reverend Eddie Mayes, who helped organize the protest. “All but one of our six school board members are white. It all goes back to the dreaded word — racism.”

Now and then, the topic of consolidating the three districts comes up. A study two years ago suggested the county could save $500,000 a year, mostly in superintendent salaries and support staff, and expand course offerings.

But there is little support for the idea. Other districts don’t want to take on Summerton’s problems — and Summerton has its own reasons for wanting to hold on to its own system. “To be honest,” says State Representative Alex Harvin, “there was no more enthusiasm in Summerton for consolidation than in Manning or Turbeville.”

Harvin, who lives in Summerton, says the school board is the one political office where blacks have gained sizable influence. Six of the seven board members are black. Only four, however, are elected. The other three are chosen by a county board appointed by Harvin, State Senator Land, and a third legislator from a neighboring county. The same board also picks the entire Manning school board. Turbeville is the only district in Clarendon County where the public directly chooses the full governing board.

“That was the communities’ consensus,” says Land. “They wanted it that way.”

Land and Harvin are political anomalies in South Carolina: white legislators representing majority-black districts. Land gets a chuckle out of being called “a brother” by his black colleagues, and he moves easily through the black communities of his district.

Even so, Land admits that the racial divisions plaguing Summerton schools are a complete puzzle to him. “I’ve been in office 20 years, and I’ve never found the key, found the handle,” he says. “It goes back to the people in that county. They have got to do it.”

A Painful Reminder

Folks with long memories still refer to old Scotts Branch High School as a “Jimmy Byrnes” school after the former U.S. Supreme Court justice elected South Carolina governor in 1950.

Hoping to stave off integration by showing the courts that separate schools could be equal, Byrnes convinced the General Assembly to equalize pay for black and white teachers and to spend the phenomenal sum of $175 million to build new black schools. About $900,000 of that was spent in Clarendon County.

In August, the new Scotts Branch High School will open on the outskirts of town on the highway to Manning. Many hope the modern and attractive building will draw white children back into classes with black children. But if history is any guide, a new building may not be enough.

Forty years ago, before the interstate was built, cars streamed through town past Summerton High School on Highway 301, the main road to Florida. Tourists seldom come this way anymore, but the former white high school remains, a boarded-up shell of its past life and a constant, painful reminder of the educational struggles that continue to this day.

“For me,” says outgoing Superintendent Milt Marley, “this is a community problem, and the community has chosen over the years to ignore it. You choose to live or die together, and this community has chosen to die. Unless they decide it’s important to educate these children in a diverse, multicultural setting, it won’t happen.”

Tags

Jeff Miller

Jeff Miller is a reporter for The State in Columbia, South Carolina. (1994)