This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

When federal courts began ordering schools to integrate in the late 1960s, many white parents across the South sent their children to private academies. The widespread resistance to interracial education impoverished many predominantly black public schools and left them strapped for resources.

In Holmes County, Mississippi, a group of activists is working to enrich the public schools by tapping the wealth of human resources in the community. With a staff of three and a small budget, the Community Culture and Resource Center has created alternative school projects that enliven education and empower students. We asked executive director Ann Brown and project coordinator Rayford Horton about their work and the legacy of segregation.

Horton: As a graduate of the public schools here in Holmes County, I understand some of the problems in the system. Many schools in the state are on academic probation, but all you hear is blame shifting. The teachers say, “The kids can’t learn,” and the kids say, “The teachers can’t teach.” No one focuses on who suffers — the kids.

I did a survey of high school students, particularly dropouts and potential dropouts, to understand what was missing. They told me there was no reason to go to school — there was nothing exciting happening. Teachers lectured from a manual, and the kids felt, “I can read, so why is this teacher reading to me out of a book?” It was boring. The only extracurricular cultural programs were band and athletics — no drama, no art, nothing.

I’ve always felt that young people have creative energy — they need to express themselves. If the energy doesn’t come out in a positive way, it’s going to come out in a negative way. Holmes County schools didn’t have any cultural programs to allow kids to express that creative energy. So you had kids on drugs, in street gangs, or just being the class clown.

I made it my mission to work with young people after school, on weekends, and across the summer to design projects that were educational and exciting. We wanted to design creative educational models that can be replicated by other communities.

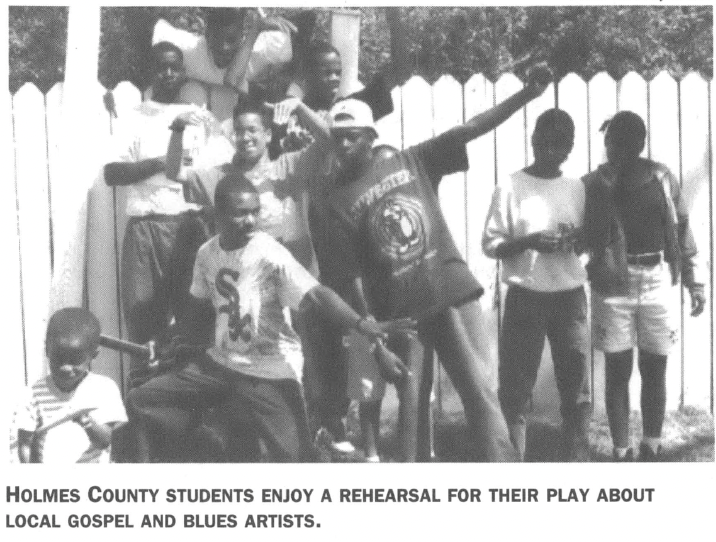

We discovered there are young people who have tremendous talents — speaking, acting, singing, playing instruments — that they never had a chance to express. So we began by having kids put together plays based on local history and culture. This year we put together a 45-minute performance on gospel and blues. The young people identified local artists and interviewed them to get their stories about how their careers in music have helped better their lives. Then we created a dramatization to tell the story, and invited the artists to participate.

The projects show young people that everyone has a talent. There’s a talent in the way everybody talks, there’s a talent in the way everybody walks. If they can use that God-given skill, they can help better their lives and the lives of those in the community.

The projects also help close the gap between the community and the schools. Most of the time when we conduct interviews with people, they have stories they’ve been wanting to tell for years. They’re excited to be able to share their experience and their knowledge with young people — about local history, their role in the civil rights movement, their art and music and way of life.

Young people can relate to things that are local — and it gives them a perspective that isn’t taught in school. They read what their textbooks say about life here in America, and they compare that to what they learn from talking to people who have experienced it. It gives them an in-depth look at themselves and their communities. They say, “I didn’t know this happened right next door to me — and it’s still happening!” They learn that history is made every day. It motivates them to want to learn.

These programs prompt a lot of young people to want to go to college and continue their education. I would say 80 percent of the kids who were part of the first projects I worked on are in college right now.

Brown: We also have a youth environmental project in a high school located in the Delta where many families have never had running water. They have to haul water and store it in containers in their homes for long periods of time. Large plantation owners in the Delta use a lot of chemicals that poison the drinking water, but there was nothing in the curriculum about it. So we developed a project to do educational awareness of groundwater and health hazards.

Our environmental coordinator Wilma Powell works in the classroom along with an earth science teacher for six weeks. She brings in resource people to lecture and show films, and students test the water and soil in their area for chemicals. When they tested the water at their school, they discovered there was no chlorinator on the water supply!

Once the students learn about the health risks of hauling and storing water, they become actively involved in organizing to get running water brought to their communities. They also plan to go to the school board to get the project institutionalized districtwide as part of the curriculum for the 1995 school year.

One of our main efforts is to organize the community to give everyone a voice in the decisions that affect them. We need a fundamental, institutional change in our school system, and that’s why we make sure to involve youth in every aspect of our work. Working side by side with adults helps young people develop leadership skills so they are not afraid to go to the school board, get on the agenda, and speak up on their behalf.

Under segregation, the three black high schools in Holmes County were called “Attendance Centers for Negroes,” and after desegregation they were still called “Attendance Centers.” When a group of young people in one of our programs learned how the schools got their names, they launched a campaign to change them. After a year and a half of organizing, they were successful in getting the names changed to ones chosen by the communities — the names of the first principals of the schools.

Horton: It’s not just the names that are left over from segregation. In many ways, the school system is still playing catch-up from that era. Even after Brown v. Board of Education, the schools were still segregated. When whites created private academies, they stripped the public schools — they didn’t leave anything behind. We got new facilities, but we lacked the resources that whites had.

It all goes back to that dollar. Teachers and administrators always say, “We could do more if we had the money.” That’s a real problem, but it’s not enough to simply give up. We say, “Use what you have.” The community has tremendous resources — let’s put them to use. Let’s make students part of the decision-making process — then you’ll see them getting more involved in their own education.

Brown: We’re trying to show that there are some things you can do without money. All you need are the bodies, the resources that you have. With the environmental project, we work with the ground, the water, the people. The people are here. They exist. They have stories they want to tell. The schools say, “We can’t teach it because it’s not in the book.” But it’s real.

We need to make education real. We tell school officials, “You may be in charge, but these are our schools and our communities, and we have to have a voice in what happens here.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.