Swamps

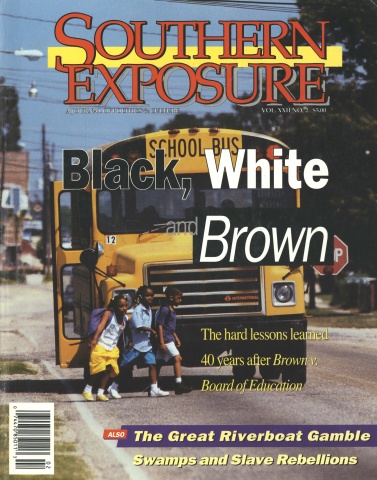

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

When cartoonist Walt Kelly created the character Pogo and his friends, he made their home the Okefenokee Swamp in Georgia. The cypress trees, still water, and alligators that inhabit swamps like the Okefenokee have become imprinted in the national mind as archetypical Southern scenery.

“It’s more than the climate,” says Buck Reed, a biologist with the National Wetlands Inventory in St. Petersburg, Florida. “It’s the whole geologic history of the South that makes it conducive to swamps.”

After the ocean receded from the North American continent 18,000 years ago, the flat coastal plain gradually became saturated with water, creating thousands of acres of wetlands where cypress, pine, tupelo trees, and shrubs now grow. In the South, these forested bottomlands, or swamps, range from the Atchafalaya in Louisiana, north to the Great Dismal in North Carolina and Virginia, down to the Okefenokee in Georgia and the Big Cypress bordering the Everglades in Florida. According to Reed, nearly half of the nation’s swamps are in the Southeast.

As humans populated the region, swamps became intertwined with their culture. Swampland, alive with deer, bear, bobcats, birds, carnivorous pitcher plants, lilies, and trees, provided fish and game for Indians and European settlers, a hiding place for runaway slaves, and a money-making enterprise for loggers.

“Old-timers used to kill alligators or spread trap lines and catch raccoons and otters,” recalls Johnny Hickox, a lifelong swamper and chief guide in the Okefenokee for 32 years. “Their main supply of fish was out of the Okefenokee.”

Some capitalized on the raw materials in the swamp. “There was a small town right in the middle of the Okefenokee on Billy’s Island back in the early 1900s,” says Jimmy Walker, manager of the Okefenokee Swamp Park near Waycross, Georgia. “There were little railroads that ran right to the center of the swamp and that was the way they hauled out big cypress logs. The money was in logging.”

But while some Southerners depended on swamps for their livelihood, others saw them as a hindrance to development. George Washington wanted to canalize and drain the Great Dismal Swamp to speed commerce. Farmers in the Mississippi Valley have long changed swampland, rich in peat and silt, into cropland. And in Florida, a population boom and modern agribusiness are shrinking and poisoning Big Cypress and the Everglades.

As a result, huge swaths of Southern wetlands have vanished. According to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Southern states have lost an average of 48 percent of their wetlands since the 1780s. The national average is 30 percent.

State and national parks, refuges, and preserves protect some swampland, but federal policy toward wetlands remains weak. “Most of the legislative movement at the national level is toward providing less protection for these areas,” says Richard Hamann, a researcher at the University of Florida in Gainesville. In 1991, then-Vice President Dan Quayle tried to redefine about half the country’s wetlands, including swamps, out of existence.

Scientific reports on the value of wetlands — combined with direct citizen action — have forced officials to back away from efforts to open the watery acreage to development. “Wetlands are an essential component of the plumbing system of the planet,” says David White, Southeast Counsel for the National Wildlife Federation. “They are extremely important for water supply, wildlife habitat, and flood storage.”

In the Everglades, the Federation is battling sugar growers whose farming practices contaminate the swamp with phosphorous. Florida citizens are pushing for a penny-a-pound tax on raw sugar to make the industry pay for the damage. Miccosukee and Seminole Indians who live in the Big Cypress Swamp want the state to halt agricultural pollution and end oil and gas development.

The challenge is to find ways humans can make a living and swamps can stay healthy. “It’s difficult to preserve a swamp,” says Margaret Shea, director of science and stewardship in the Kentucky office of the Nature Conservancy. “You have to protect the whole watershed.” To that end, the Conservancy bought 284 acres of prime swampland to save it from agricultural pollution. “We try to work with the landowners in the watershed to promote good land management practices,” Shea adds.

For those who grew up in and around the swamp, such efforts are essential to preserve their way of life. “When I go in the swamp,” says Okefenokee guide Johnny Hickox, “it’s just like taking a dose of medicine.”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)