This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

When civil rights attorneys argued the landmark case Brown v. Board of Education before the U.S. Supreme Court, their goal was to ensure equal education for all children, regardless of race. They wanted to integrate white and black schools — and to do that, they had to convince the court that segregated black schools were inferior to white schools.

They made a compelling case, exposing the all-too-real and brutal inequities of segregation. But in the process, they also fueled the popular notion that all segregated black schools were entirely “bad” — nothing more than dilapidated schoolhouses with poorly trained teachers who offered impoverished black children a second-rate education.

For the past five years, Dr. Emilie Vanessa Siddle Walker has been researching what was “good” about African-American schools during segregation — what teachers, students, and parents valued about them. As an elementary student in North Carolina, Walker witnessed desegregation firsthand when she was transferred from an all-black school to a newly integrated institution. She went on to earn her doctorate in education from Harvard University, and is now assistant professor in the Division of Educational Studies at Emory University in Atlanta.

But Walker found herself drawn to stories she heard in her community about segregated schools. Her research has led her to produce both a film and a forthcoming book tracing the history of the Caswell County Training School from 1933 to 1969. Both are subtitled simply: “Remembering the ‘Good’ in Segregated Schooling for African-American Children.”

SE: How did you get into researching African-American schools?

Walker: I am originally from Caswell County. I was teaching at the University of Pennsylvania, but went home during the summer that the school board was talking about closing Dillard Junior High School, which during segregation was called the Caswell County Training School. There were a lot of conversations in the air about the school, and a lot of lamenting among members of the community that the school board was getting ready to close it.

In particular, I remember the conversations with my mom. She would say, “Oh, you know, they’re getting ready to close the school,” and “Oh, Mr. Dillard worked so hard for this school,” and “Oh, it was such a wonderful school, and it’s getting ready to pass from the scene and nobody will ever know what it was like.” And I’d hear the same thing when I would go to gas stations and around in the community. I was privy to these conversations by virtue of the fact that I was a product of the community. They weren’t talking to me as a researcher.

In ethnographic research we talk about “making the familiar strange.” That summer, something that had been familiar to me — I’d known about this school all my life — suddenly became very strange. It clicked that what people were saying to me was not the same as what I read as a professional about black schools. When I read about them, everybody talked about what was wrong with them. Yet here I was in the community, listening to people talk about what was wonderful about a poor, black, segregated school and bemoaning the loss of its memories if it were closed.

That was the beginning. I visited with the wife of N.L. Dillard, who had been the principal, and with a couple of former teachers. These weren’t really formal interviews, but just following through to see: Am I really understanding these people to say that they liked their segregated schools? Is that really what I’m hearing? After several informal talks, it became very clear to me that that was exactly what I was hearing. And that’s how the project started.

SE: Once you were convinced that there was something worth researching, what did you do to try and understand it better?

Walker: For starters, I began conducting open-ended interviews with former teachers, students, parents, and administrators who had been involved with the school. This included interviews with those who had a close relationship with the school, as well as those who did not. I wanted to understand what was good about the educational environment from the perspective of those who were participants.

Using the perspective of the participants is an important distinction. In this research, “good” is not based on external variables such as test scores, or the number of PhDs students received, or something like that. “Good” means: This was an environment that the participants valued. They deemed it as good. So I wanted to understand: What did they think was so good about it?

I also began collecting documents to confirm that what people were saying was true in “real time” and not just nostalgic. From the vantage point of now, our past usually looks good. Last year looks good to me now, because I didn’t have a daughter then and I could take a nap. The collection of documents was thus very important because I needed to know that this was the evaluation of people at the time it was happening and not just a nostalgic account.

Unfortunately, most school-based documents from the era had been destroyed. People apparently assumed there was nothing significant about the segregated schooling of African-American children, so there was no reason to keep anything. The school only has two or three yearbooks and a very thin file folder — that’s all. So we had to recover a document base from people’s attics and drawers — yearbooks, pictures, letters, school newspapers, teaching bulletins, books, etc. In addition, we reviewed all available public documents, such as school board minutes, newspaper accounts, and principal’s reports.

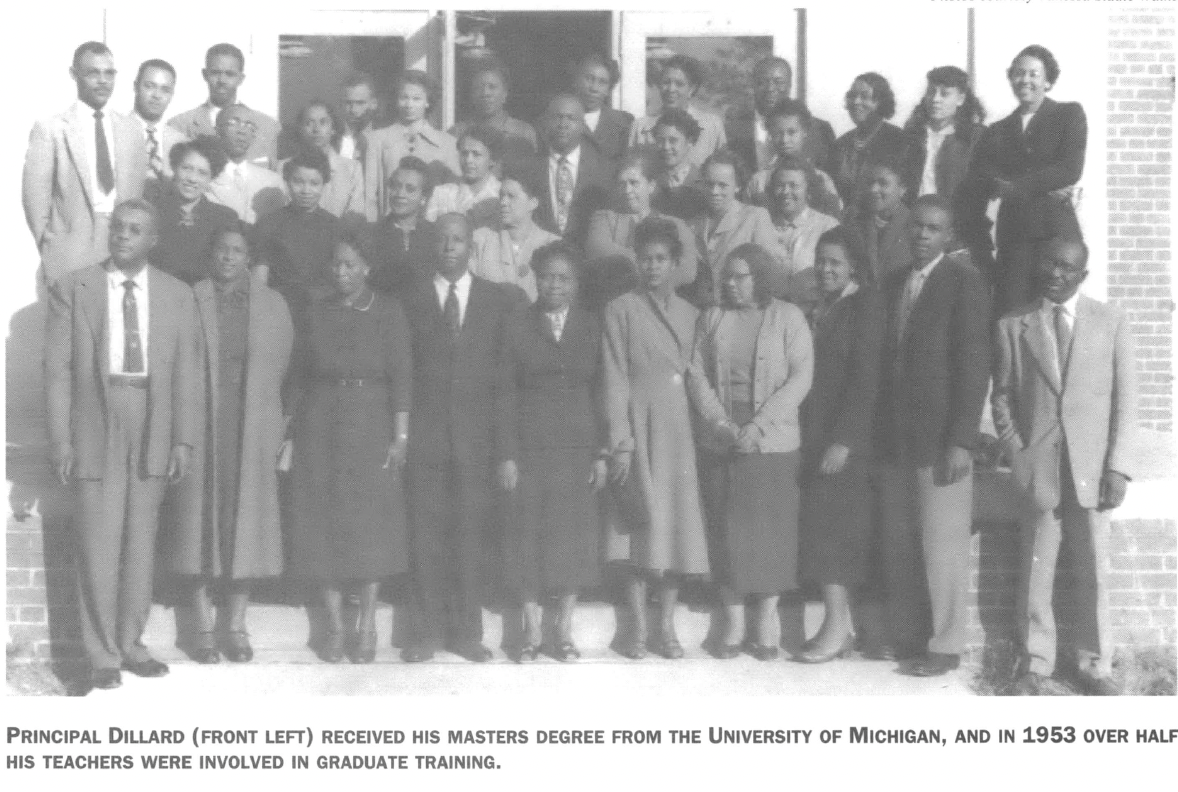

One of our most important finds was a Southern Association report when the school was accredited in the early 1950s. I have the hand-written notes of the principal and faculty members as they surveyed the school to prepare for this external evaluation. Because they are hand-written notes and not the formal report, I think we can be fairly confident that they reflect how the participants were seeing themselves at the time. I also have the evaluation that the Southern Association sent back to them, which shows how other people rated the school. Since these documents confirmed the interview data, I can be reasonably confident that the themes I’m finding aren’t just nostalgic, but that they reflect what was really going on.

Once I understood what people valued, I conducted much more focused interviews. I wanted to understand the parameters: For whom was the schooling good? Under what circumstances? Who got omitted? I was much more likely to call up someone I’d already interviewed and say, “Mrs. Boston, I understand that the parents and the school interacted very comfortably for the most part. Can you give me some examples of when they didn’t?” We now have hundreds of pages of documented material and over 100 interviews.

SE: In your work you talk about two things that were “good” about the school — interpersonal caring and institutional caring. What’s the difference?

Walker: Caring means that if I’m interested in your well-being, I’m going to attend to your needs. When people think about the importance of caring in schools, they generally think about interpersonal relationships between students and teachers.

These relationships existed in the school, but I’m also saying there are other things that teachers and administrators did that can’t be reduced to interpersonal caring. In fact, the institution, through its policy, tried to understand the needs of its students, and to see that those needs were met — which is also caring. It is the human interactions and more, because it involves a planned structure for caring about students.

SE: What are some examples of interpersonal caring?

Walker: The teachers and the principal actually assumed responsibility to be certain that children learned. A child would not be allowed to come into a classroom and disengage, either by going to sleep or refusing to participate. The teacher took the responsibility to pull that student aside and ask, “Did you have breakfast this morning? Did you have a fight at home? What’s wrong?” One teacher I interviewed told a student, “Why are you so evil and snappy today? We’ve all got to live in this classroom and get along with each other. If I can help you, let me know.” And the students would generally respond by telling the teachers what was wrong.

Teachers cared about more than whether the child could make subjects and verbs agree. They took responsibility for the whole student — to understand that child as a person and any problems that might interfere with his or her learning. They cared about who the students were as people. They knew them.

Before school and after school and during study periods, students would go to classrooms and just sit down and talk to teachers. Teachers would take time to talk to them about life, what it meant to be a student, and why education was important. Teachers told them that as black children, they had to be “better” — that was the word that was often used — in order to be accepted.

Even the principal made himself available to talk to students. One of his ways of managing was to walk the halls. He was constantly in the halls. Students said, “You didn’t have to make appointments to go and see him. You always knew he was going to be there.”

Even in the last years when there were something like 1,000 students, the principal knew the name of every student in that school. One student reports, “You could have your back to him and be running away from him, but he could get on the intercom and say, ‘So-and-so, come to the office.’” So a student couldn’t just fade into the background and be invisible. The students were known.

There are even numerous instances of the teachers and principal giving money to children. If they didn’t have money for lunch, for example, someone gave them the money. One of the most moving stories I heard was from a former student who talked about how her parents couldn’t afford to send her to college. She had not even signed up to take the SAT. The day of the test, the students were already on the bus to go to a neighboring high school to take the exam. The principal came up to her classroom, got her out of class, put a ticket in her hand for the SAT that he had already paid for, gave her two pencils, and put her on the bus to go take the SAT. She took the test, and he helped get her into college and get a scholarship.

Today she is a teacher. She talks about how, but for that intervention, she would not have been able to do that.

She’s not the only example. A librarian asked a student, “Where are your gloves this morning?” It was very cold. The student said, “I don’t have any.” For Christmas the librarian brought the student some gloves and wrapped them up and gave them to her as a present.

Students remember these examples of interpersonal caring more than teaching methods. It wasn’t the methods that motivated them — it was the way the teachers and principal cared about them as human beings. They responded to that caring by not wanting to “let the teachers down.” They talk about how they felt like a family, and they would try to excel in their school work as a result. So school, then, became personal.

SE: What are some examples of institutional caring?

Walker: I emphasize institutional caring because I think people might reduce the segregated school into, “Oh, yeah, wasn’t that wonderful and touchy-feely. Oh, people were just nice.” And they were nice. But they did other things that demonstrate a planned approach to caring about students.

Caswell County is small and rural, and written documentation of the era demonstrates that educators were very clear about the needs of their students. They talk about how the county had no museums, no lyceums, no forums — no nothing except a few pool halls and a couple of theaters. Other than church, students had very few opportunities to do anything. They didn’t go see things, and they didn’t get to do things.

So the school felt a responsibility to expose students to things they wouldn’t ordinarily have the opportunity to see. They wanted to give them opportunities to develop leadership skills, to learn how to talk in front of audiences and things like that. You see it in their written philosophy, and you hear it over and over in the interviews with teachers. They’re very clear — they wanted to push each student to his or her fullest potential.

How do they do that? One way is through special activities. Lots of schools had activities and clubs; what’s significant is that they overtly designed these activities to meet the particular needs of their students. I’ve been able to count as many as 53 different clubs that were offered in the school between 1934 and 1969. For a rural school, that’s quite phenomenal.

You name it, they had it — courtesy clubs, debating teams, history, science, Future Teachers of America. There were academic clubs, clubs that would teach you about certain kinds of hobbies, clubs that worked on moral development. Where else would a child in rural Caswell County learn how to do photography, but for a Lens and Shutter Club? Where else would they get to practice debate if they didn’t have the opportunity to do that at school?

Consider a normal year, in which perhaps 20 clubs might be available. That meant there were four opportunities for leadership available in each club — president, vice president, secretary, and treasurer. That’s a total of 80 leadership spots. “If you couldn’t be president of the student government,” one student told me, “there were still lots of other things you could do if you wanted to be a leader.”

That to me is an example of the institution identifying the needs that its students have and overtly trying to meet those needs. The chapel program is another response. Once a week the entire school met in the auditorium, and students from each club were responsible for presenting the program. Students learned how to be in an audience and how to be the speaker, and the principal got a chance to talk to them as a group about the importance of education.

Another example of institutional caring is the homeroom teaching plan. They had homeroom teachers in ninth grade that rotated up with them through twelfth grade. In education we are now talking about this as a “school within,” but they were doing this a long time ago. Do you know why? Because they said, “Students need to have a sense of belonging in the school. So if we give them the same homeroom teacher every year, then they will have a feeling that this teacher is looking out for us.”

These things weren’t incidental. They were planned ways of meeting the needs of the children. That’s why I call it institutional caring.

SE: How did your research make you think about your own schooling? Did it change your understanding of your own past in any way?

Walker: I’m a product of both integrated and segregated schools. Though I remember very little of it, I attended Caswell County Training School in first, second, and third grades. I was in another segregated school up until the fifth grade, when the schools integrated.

I never really thought about segregated schooling at all, in terms of what kind of influence it had on me. It was just a fact of my life. Listening to people talk about it has helped me rethink what I experienced in the segregated school environment. I am now beginning to realize, “Geez, even though I was a child, I, too, am a product of all the things the institution did to make children feel good about themselves.” How important was it for me to have experienced that kind of warmth in the early years of my education? I don’t know, but it certainly has raised that question for me.

I also cannot help comparing what I experienced in the integrated environment with what people had experienced 10 years before me in the segregated environment. And the truth of the matter is, I did not have the opportunity to do all the things that they talk about. That’s sad. The opportunities simply were not placed before me in the same way that they had been before.

SE: How did the teachers you’ve interviewed feel when the schools were integrated in 1969? Did they regret losing their school?

Walker: Asking that question is not a part of my research, although it has come up informally in some conversations. I can speak from that perspective only.

The opinions vary. Some teachers were amazed at the resources that white children had. Others felt their own school was quite good. Those who have talked about it certainly seem to feel that the education their children received was good.

Many teachers lament that they were not able to push African-American children to excel in an integrated setting. They couldn’t single them out, so they felt as though they couldn’t communicate the values they had tried to communicate before.

SE: Did you get a sense from them how they felt the process of integration could have been handled differently?

Walker: I’ve never heard them talk about it. My project is not about whether integration is better than segregation — that’s not the research question. The teachers and the principal saw integration as a political process and they stayed away from the politics. The only question I have heard them raise is an academic one: “What’s going to happen to the children?”

I will say this. When Principal Dillard died in February 1969, the administration was divvying up his teachers — making decisions about which would stay with him at the junior high school and which would go over to the former white high school. He was not an old person — he was in his early 60s — and nobody thought he was sick enough to die. He had a lot of concerns about what was going to happen to the children under integration. His wife says he said over and over, “What is going to happen to the children?” People in the community think that integration killed him — that his concerns were significant enough to cause an earlier death than he might otherwise have had.

SE: I can imagine people reading about this small, rural school from the past and thinking, “Sure, but the world’s a different place now — drugs and crime in the school, families breaking up, students under stress. We can’t do the things they did today.”

Walker: One of the things I’ve argued over and over is that I don’t think that we should just take everything they did back then and move it to a different setting. That won’t work. They were creative and figured out how to address the needs of their students within the constraints imposed upon them in their time. It seems to me we have to be equally creative in thinking about the constraints imposed upon us and figure out how to solve the problems in our time.

Not that we should minimize what they did in their time. Here were people who were being denigrated by the larger society. They were not being given facilities. They were not being given resources. For many years, the teachers were not making as much money as their white counterparts. They had no more hours in a day than there are now. But one thing they did have was a different definition of what it means to teach.

Does that mean we need to adopt their definition of teaching? Not necessarily. I think that this school provides a context, a launching pad if you will, where we can begin to think about school reform. In other words, it helps us ask the right questions.

For example, one question people today often ask is, “Why are so many African-American children not performing well in school?” We center reforms on the students — what’s wrong with them, and why can’t they do better?

When we understand something of the history, though, we also see the importance of asking questions that relate to teaching. Where does teaching begin? Where does it end? Do we have common definitions of teaching? Do we utilize models of teaching that worked successfully for at least some African-American students in the past?

I often hear the question raised: “How do we get parents — usually meaning black parents — to be interested in their children’s school?” If you know anything about the history of segregated schools, you know that the parents were involved. So the question isn’t how do we get them to become involved, the question is why did they cease to be involved, and how do we get them to come back? If we ask the wrong questions about reform, we’ll get the wrong answers. The historical context should help us ask better questions.

SE: You seem very conscious that your work could be misinterpreted to advocate a return to segregation: Black schools were good for black students, therefore we should have separate school systems.

Walker: I do not doubt that some people will try to interpret it that way. The only way I can counter that is by making very sure, both in my writings and in my conversations, that I’m very clear about what I mean.

I am not saying that segregated schooling was all good. In the first chapter of the book, I spend a lot of time talking about the inequities that African Americans faced — the poor resources, the lack of equipment, the failure of school boards to respond to needs of children. That is the part of the picture of segregated schools which we documented to get the Brown decision, and nothing I’ve done discounts the truth of that picture.

What I argue, however, is that that is only part of the picture. We have not focused on how, in spite of all the inequities, African-American principals and teachers were able to create learning environments that functioned successfully for children.

Take the Caswell County Training School. When the school system integrated in 1969, the segregated black school was larger than the white school. It had a two-story auditorium with a balcony, a gym, and more classrooms. Unlike the white school, it was accredited by the Southern Association of Schools and Colleges. Yet it became the junior high school. Black children left their accredited, segregated school to go to an unaccredited white school which had fewer facilities. I think that flies in the face of everything we think about integration.

If we’re going to understand the segregated schooling of African-American children, we have to understand not just what was done to us. We also have to understand how people worked around that system for children. That’s why we need the whole picture. It helps us to understand black children at a time when they were learning.

SE: The subject of what was good about segregated schools has been off-limits for a long time. Why are scholars beginning to return to it now?

Walker: Frankly, I don’t really know. Perhaps people are looking at history because they are looking for answers. It seems to me that integration has not given us all we hoped. It’s given us facilities and resources, but in the process, as Principal Dillard predicted, we’ve lost something our children needed. That something is missing is evident in almost every research study you pick up. By and large, African-American children are not succeeding as we would like them to in school, whether they are in integrated or de facto segregated settings.

People are trying very hard to increase the educational success of African-American children. Perhaps looking back at segregation is just one way of trying to get a whole picture — to help us understand how to create reform that will be lasting and meaningful.

SE: What reforms would you initiate if you were running the schools today?

Walker: I don’t think my research gives answers, but rather raises questions. For example: Do institutions still demonstrate caring about African- American students and their success? Are African-American children being given opportunities to get up on stage? To demonstrate their multiple intelligences? To develop leadership skills in school?

An African-American student at one inner-city school told me how he took a field trip to jail. As far as I could tell, this was not a part of a class. While they were there, some of his friends started misbehaving and the teacher said, “Lock them up.” They were locked up, and one of them was actually left in the cell while the other students went for lunch. A policeman told some of the others, “Come here, let me fingerprint you. You look like you’ll get in trouble, so we’ll see you again.”

This young man was terrified. The school may have been well-meaning — attempting to help students understand where they did not want to wind up — but that’s not the effect it had on this student.

I asked the same student, “Do you ever get to participate in school assemblies?” He looked at me like I’d dropped off the moon. He said he seldom gets to go to assemblies, much less participate in one. From our conversation, it would appear that nobody’s looking at what he may be able to do and giving him opportunities to showcase his talents. Why isn’t he getting to do that?

I asked him, “Do you all have clubs in your school?” Know what he told me? He said, “Yeah, but those are just for the white folk. They think black people are too dumb to be in their clubs. One of my friends tried to go get in the performing arts club and he was told that he was not cooperative enough.”

Here we have a child who’s in school — well, he was. He’s dropped out. But was he being cared about on an interpersonal level? Did the institution have policies that demonstrated a commitment to him as a human being?

Reform is not just a checklist: Do we have assemblies? Do we have clubs? It’s a deeper issue: Who are the children? What are their needs? And have we put institutional policies in place designed to meet those needs?

A teacher at Caswell County Training School had a child who was driving her nuts because he talked all the time. She punished him for being disruptive, but she also found a way to utilize his abilities as a talker. She put him in charge of the class science project, so when they had the school science fair, he was the one who presented how their volcano worked. He’s a talker? Fine — put him on the debating team.

I wonder if talkers in school today are sent to the debating team, or if they are sent to detention hall? These are some of the kinds of questions we need to ask.

These are hard questions, and I don’t raise them to indict teachers and principals who are working under very difficult circumstances. I have been a teacher, and I understand how intense the pressure can be. But I think they’re the questions that have to be raised if we’re going to start to look at reform.

The answers for each school may be very different. For me, there’s not a reform agenda that mandates what we do for every student, every teacher, every school, everywhere. It’s more individual than that.

I think we have to take history and use it as a mirror. Let’s look into the past and let it help us see ourselves for who we are now. Then we can begin to ask the questions that will help us figure out how to better educate our children today.

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.