Racial Reading

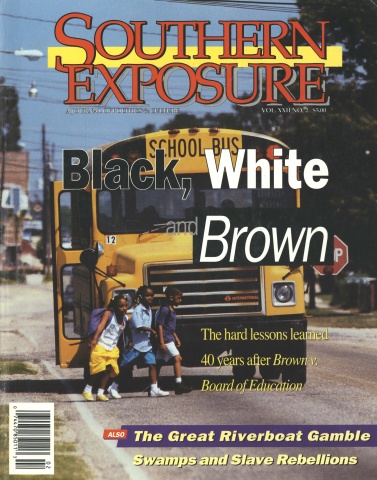

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

Every human society needs stories. In fact, story is obligatory, a means of defining and embellishing humanity. Our lives are saturated with what I call imperative fictions — stories and myths that influence our thinking and our behaviors. In America, we use one kind of imperative fiction — race — to classify and differentiate, provide warrants for our notions of superiority and inferiority, buttress certain public policies, and produce a wide range of psychological conditions in the body politic. “Race” is the most powerful concept in the national mind and the most problematic item in the American social contract.

Literature — as well as other forms of telling and writing that evade easy definition — gives us some of our most revealing conversations about race. And in no region of America are the production and consequences of these fictions more brilliantly displayed than in the South. We Southerners have always been linked to the invention of race, to the social inscription of race in our civic covenants. Race is never absent from our actual experiences nor the language we use. It is broadcast in our thought and culture at all ranges, particularly at the “lower frequencies” in which Ralph Ellison’s nameless, invisible man hinted he might be speaking for someone.

Southern writers are virtually condemned to voice that pervasive power in their works, and unless we want to play deadly games of self-deception, we do not evade the presence of race as we read and make meaning of literature. As Kwame Anthony Appiah puts it with nice discrimination in Critical Terms for Literary Study, “American literature and literary study both reflect the existence of ethnic groups — the very contours of which are, in a certain sense, the product of racism.”

Many years ago, I was accused of taking literature too seriously, of believing that writers of fiction and nonfiction actually intended to create works that make a difference for their readers. The accusation was accurate. Like singer Isaac Hayes, I don’t mind standing accused of believing that the discourse of race in Southern fiction influences our understanding of how American culture and thought get arrested by words. After all, why do many Southern conversations resemble debates between Richard Wright and William Faulkner?

There is an urgency in my remarks about race and Southern literature as I write a collection of essays on the subject. The need to confess ethnic-specific habits of reading comes from my having lived in the South for nearly half a century and from understanding where the everyday conversations of my generation are anchored. The urgency comes also from the pleasure of finding in Toni Morrison’s Playing in the Dark a confirmation of how productive it is to redraw the boundaries of literary and cultural studies. My recent writing and editing have caused me to meander in the tropic zone of race, Southern literature, and imperative fictions. I call these meanderings “digressions.”

Digression One. Writing about the Southern rage to Tell About the South, Fred Hobson (one of the better intellectual historians) claims “in essence all writing about the South, fiction or nonfiction, seeks in one way or another to explore and explain the region.” Such writing explains more than region, however — it explains human action and reaction in a space that is language, and in a place where we do things with words.

To the extent that this “fiction” named race constitutes the bulk of America’s master narrative, we can profit by backtracking to the 1960s. Questioning the meaning of the civil rights movement is one way of exposing what is present but often hidden by the distortions of color.

Much of Alice Walker’s work provides instances for questioning the 1960s. Her essay “The Civil Rights Movement: What Good Was It?” appeared in American Scholar in 1967. The subtitle gives the false impression that the movement was over; in fact, there is something timely, very fresh still about this essay. After reviewing the reasons that the disaffected offered for announcing that the movement was dead, Walker proceeded to write how the movement had provided “an awakened faith in the newness and imagination of the human spirit.” The awakening is not couched in terms of race, but the racial implications seem as obvious as do those pertinent matters of gender.

“Part of what existence means to me is knowing the difference between what I am now and what I was then,” Walker writes. “It is being capable of looking after myself intellectually as well as financially. It is being able to tell when I am being wronged and by whom. It means being awake to protect myself and the ones I love. It means being a part of the world community, and being alert to which part it is I have joined, and knowing how to change to another part if that part does not suit me. To know is to exist; to exist is to be involved, to move about, to see the world with my own eyes. This, at least, the movement has given to me.”

The ability to see, to know, to do that Walker speaks of was gained in the 1960s and ’70s for many by assaulting the more obvious signs of institutionalized racism in the South and elsewhere, and by forcing the American legal system to either make constitutional promises real or stand naked before the world as a paragon of systemic inequality. By contrast, recycling race in Southern history and literature produced grand illusions. One imagines that Alice Walker’s need as an artist to tell about the complexity of the civil rights movement was grounded in the recognition that personal change was real; social change was at best cosmetic.

In Meridian, her story of the 1960s South and the consequences of the civil rights movement, Walker provides a frame through which we gaze upon racialized scenes in the American Dream/Nightmare (take your pick). It warns us of the delusions in our rememberings about the 1960s, the South, and America in general. The color-coding of “race” and the magic of fiction often make us blind. Once we account for the black and white of social struggle, we think we have knowledge. Instead, all we have is the conflicted mindscape to which race has directed us.

Yes, we sit and break bread together in spaces that were forbidden 30 years ago. And the more we talk about the past in the light of the present, the more the bridges we thought we had made collapse. We have to perform the civil rights movement all over again. Meridian intensifies the feeling that talking about the South and race and humanity is inadequate. We must coordinate action and talk.

Digression Two. Before the advent of reader response theory, say in 1955, asking what happens when a black Southern male reads narratives by a white Southern female might have been considered, at best, an oddity, and, at worst, an excuse for the good old boys to sponsor a lynching. Now it is okay to say race and gender expose some qualities of the “Southern” in such writings. The subjective black male perspective liberates something for which we still do not have a good name from the musty closets of the unsaid.

As a black male reader, I am caught up with the white female writer’s use of language (especially in capturing the deeper rhythms of Southern talk), manipulation of plot, and sense of place. But my fascination is disturbed and displaced by the writer’s seemingly inevitable smirk — the attempt of Southern whites to seek their salvation in the arms of Southern blacks. I recall in particular the moment when Nelson Head, the grandson of Flannery O’Connor’s “The Artificial Nigger,” feels the desire to be embraced by the black woman (the mammy surrogate) of whom he asks directions in Atlanta.

What emerges in my reading differs depending on the writer. Ellen Douglas, for example, does not smirk, and her novel Can’t Quit You Baby is an honest, stellar example of the writer’s problems with race as social construction, as a filter for the interdependence of white women employers and their black women domestics. It is no accident that the tone of her novel is controlled by the poignancy of Willie Dixon’s blues.

By contrast, the controlling music in Ellen Gilchrist’s short stories and her novel The Annunciation is not the blues but the pavane — a stately European court dance. That makes all the difference, producing the strongest contrast of consciousness between myself as a reader and Gilchrist as a writer.

As a writer, Gilchrist is conscious of a South that has to do with plantations (land, privilege, and shallow aristocracy), with class and its symbolic costumes and rituals, with great expectations that are often reduced to flags in the dust, with woman’s plight, and with the hysteria that inadvertently makes the male myth of Southern white womanhood primal in the enactments of race.

As a reader, I am conscious of a South that has to do with small towns (the grubbiness of making a living), with the necessity of group interdependency where class as such must be secondary, with finite expectations that often rise to surprising heights, with male assertiveness and sexism (the endless contest for power, especially in the bitter not-to-be-spoken-of complicity of males, black and white, in their separate and unequal campaigns to keep women in their places), with the drama of racial discord, and the heavy burden of responsibility for self and others.

The values implicit in my consciousness and that of Gilchrist are in conflict, for they are derived from parallel Southern histories that are marked by race and gender. In short, the laws of physics make it possible for white women and black men to be located in the same geography, but the laws of consciousness ensure that we inhabit very different conceptual spaces.

My immediate response to Gilchrist’s fiction is that it is well-crafted, turning as it does all the clichés of Southern fiction inside-out and upside-down. My more cautious valuation is ambivalent. The fiction contains wonderful insights about the modern South, its individuality, and its quest for liberation. But it is “self-centered” and indulgent. It is embroidered with its own stereotypes of the Chinese, the Jews, and Southern blacks (perpetuating myths of kindness, innocence, and sexuality). And it invokes the black voice that speaks for the white, as if the white voice is incapable of speaking for itself. (Check out how many stories depend on the maid’s telling the story of her frustrated mistress.)

To view Gilchrist’s work from the perspective of a black Southern male is to see at once the benefits and the shortcomings of the Southern fiction of race. Hunting around in the swiftly resegregating South for the better nature of humanity is one hell of a task, especially when some of the fiction is working against you.

Digression Three. There is a primal myth of interdependency in Southern literature — a hedged movement toward a longed for and unattainable racial transcendence. This governing myth is expressed neatly in a snatch of dialogue between two Vietnam veterans from Mississippi in Larry Brown’s novel Dirty Work. Braiden Chaney, a black veteran, tells Walter James, a white vet, a story that highlights our Southern heritage of black-and-white conflict, dependency, and denial of genuinely human affinities:

“You think you got trouble? You don’t know what trouble is. Trouble when you laying in a rice paddy knowing both your arms and legs blowed off and are they gonna shoot the chopper down before it can come and get you. Trouble when they pick you up and you ain’t three feet long. The people in my fire team started to just let me lay there and bleed to death. Cause they knowed I’d wind up like this if I lived. Knowed I’d lay like this no telling how many years. They ever one of ’em has come to see me. And they each said the same thing. You know what that was?

“We wish we’d left you, Braiden.

“You been sent to me, Walter. You been sent and I ain’t gonna be denied.”

My American and racial experience forces me to talk back to the novel: “You wanna bet, Braiden? The bond between you would not be the same if you and Walter weren’t both the damaged resources of war. It would not be the same at all.”

The importance of Larry Brown’s work is that he is one of the few voices for the good old boys, the poor and lower-class whites, the voice that gets muted in Faulkner. Faulkner’s protest fictions speak about that voice, not in that voice. Larry Brown is forcing a confrontation with the ignored Other (white) who is the racial Same (white). And that is a very good thing, because Brown inspects “whiteness” from the inside. He provides a special window through which I can direct the gaze of my “black” eyes. When Brown’s first book, Facing the Music, won the literature award from the Mississippi Institute of Arts and Letters, many members of the august Institute shook their heads in dismay and disbelief — “But he doesn’t speak for us.” No he doesn’t. He speaks to you.

The urgency to do my own kind of telling about race and Southern literature is fed by the sense that we are all other than what the fictions claim we are. The fiction of race as social instrument will not disappear, nor will the literary fictions produced under the anxious influence of race. The imperative is in the rhythm of American history and life. Whether you sense that or not depends on whether you are blind, like the man who bumped into Invisible Man, or blessed with an eagle’s eye.

Perhaps imperative fictions can give eyesight to the blind. But it is not easy to be an American or Southern reader. You keep discovering that you are a character in the story.

Tags

Jerry W. Ward, Jr.

Jerry W. Ward Jr. is Lawrence Durgin Professor of Literature at Tougaloo College in Mississippi and co-editor of Black Southern Voices. He is currently writing a collection of essays under the title Reading Race, Reading America. (1994)