Holding Ida

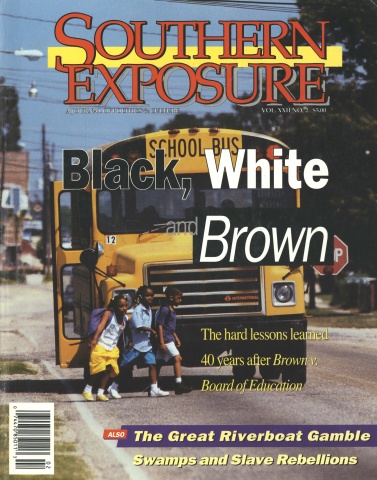

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

Last night there was all kinds of commotion. Ida Hedgecock came home all huffed up. Grabbed up into an old pickup full of men and held down in the back by her arms and legs by foreigners who talked gibberish. She prayed to Jesus and found herself sitting right on her front porch. She’d never had a prayer answered so fast. They didn’t really hurt her, thank God, but if not for sweet Jesus they surely would have. Praise him, she thought as she sat on her front porch glider thinking about how she’d kicked one of them fellows good when they was getting her in that truck bed.

All that was bad enough. Rousted by strangers. Manhandled by foreigners. Then to top it off, she couldn’t find a match to light the cook-stove. Ida never liked that electric. Couldn’t get it to work any more anyway. Whatever Ida did the eyes stayed cold and black.

Old ways are the best, but only if you have matches. No matches, but she found food in the icebox. She ate Fig Newtons and bologna, took a whore’s bath, and went to bed. Damn him. She went to bed all by herself and was cold and stiff all night.

Ida Hedgecock is peering out her kitchen window this morning. She is dressed like she has dressed every other day of her adult life, a cotton print, today navy with tiny yellow roses, cinnamon beige stockings rolled and tucked in place below her knees, black lace-up shoes with just a little bit of heel and worn at the balls of her feet to the point they might crack open at any moment. Over her dress she wears a bibbed cotton apron, faded and speckled with yellow and white daisies, two large patch pockets at the bottom and white brica-brac at every seam. Her hair is white, tinged with yellow, tucked and pinned into a roll below the crown of her head. She turns from the window and, with a slight tremor, reaches for her black-rimmed glasses. She is 81. She is troubled.

To begin with, Ida’s husband has not come home in several days. Ida has lost count. His habits have been mighty strange lately. He doesn’t eat anymore, and he never sleeps in the bed. Until a short while ago, he had slept in that high poster cherry bed every night for 65 years.

She saw him yesterday walking through the south pasture toward the river. She followed him for quite a ways but never really came close enough to call his name so he could hear it. He hadn’t heard good since he came back from the war. He said an explosion had blown out his eardrum. She was right on his trail until strangers stopped her. Said she shouldn’t be out by herself and took hold of her. Put her in a truck and brought her home.

They never hurt her, though. She thanked God for that. No thanks to Hedge who should be God’s agent in such things. Not that she is questioning God. She knows better than that.

Recently Hedge has been coming around talking to Ida at odd hours of the night when he should be sleeping or in the middle of the day when he should be tending to horses or cows or chicken coops or feed corn. And he speaks on strange subjects. He says he is salvaging, collecting parts of things and holding them in a special place. “When the time is right you’ll see,” he tells her.

Talk like that and all his carrying on is getting on Ida’s nerves. Every bit of it. But just as he has done for that same 65 years, when her hackles get raised he touches the small of her back in the spot that has always seemed made just for the resting place of his hand, and he says, “You’ll see.” It has always paid off for her to trust him when he says that. But these days it is hard trusting anything he says or does because he isn’t acting himself.

This morning, as if Ida isn’t having enough troubles, there is a man in the yard. A strange man in blue-gray coveralls and a yellow hat has been in the front yard all morning digging post holes. Chuck. Chuck. Chuck. It started just after light.

It is not Ida’s habit to speak to strangers, and this surely is something Hedge should be tending to, but he isn’t on hand. So unlike him. So unlike Hedge to leave her unprotected.

Why would a strange man be digging holes in my yard without so much as a may I? she says to herself. What could he be planting in those little holes?

“Hedge!” she hollers on the chance that he’ll come. Nothing.

Ida begins to feel hot. Everything around her fades into whiteness and then comes back. She moves toward the window as she recovers, putting on her glasses.

“Who the hell is digging holes in my yard?” she says in a loud voice. Ida cranes her neck to get a better look at the man through the kitchen windows over the sink. She can’t see him well. He has just moved beyond the shrubs, but she can hear him chuck, chuck, chucking into her grass. Probably into her flowers.

Ida drags a turquoise dinette chair screeching against the peeling linoleum rug until she has it positioned in front of the sink. She slowly climbs up onto the chair. Once she has both feet unsteadily placed on the seat, she lifts her right foot to put it into the sink.

“Mother! What in the world are you doing?” Nancy’s voice gives Ida such a start from behind that she jerks and begins listing too much in one direction. She can feel herself falling as if in slow motion. She makes a little noise as she falls. “Ughhh.”

Nancy’s hands go nimbly around Ida’s body and the two women, as one, stagger backward and fall. Nancy cushions Ida’s fragile bones as much as she can.

“Mother,” Nancy speaks as if to a child she has lost all patience with but still refuses to yell at. “What were you doing climbing in that sink? God.”

Ida says nothing.

“Please roll over,” Nancy says to her.

Ida grunts.

“Careful,” Nancy says. “Are you all right?”

Ida grunts again and moves to the right. With a little thud she is off Nancy’s stomach and lying on her side, her wrinkled cheek against the clean cool familiar linoleum.

Ida’s young face rests against the cool linoleum. She is wearing nothing but a white petticoat. It is July and sweltering hot. Ida’s mother is sitting on the davenport looking at photographs with Aunt Osie. They are laughing at something they remember about their father while Ida traces the pink flowers of the new linoleum rug in the parlor. The old linoleum has been moved to the kitchen as always and the pretty new flowers are in the front room. Her mother’s shoes are inches from her face, all those hooks and string going up under her skirt and petticoats. Aunt Osie’s two-tone shoes from Chicago have buttons. Aunt Osie’s feet are smaller than her mother’s because Aunt Osie is so short, only four feet ten inches. She is like a little bitty grown-up. Ethel can already wear all Osie’s fancy shoes and plays in them when Osie is not around. Ida is not supposed to tell this.

Ida’s child body melts against the smooth chill of the floor, a relief from the wavy heat she has just seen rising from the ground outside. Her tanned limbs sprawl, trying to get as much of the cool surface against her body as possible. But her mother reaches for her, lifts her up saying, “Ida, honey, don’t lay on the parlor floor like that. It’s not lady-like. Jump up and take your father his lunch.”

Ida likes to walk the three miles to the hosiery mill, even when it’s hot. Sometimes she pretends to be a Bible character, someone fleeing Egypt with Moses, walking across the dry parched bottom of the Red Sea, hurrying before God lets the waters crash together to drown Pharaohs’ men. She likes to hear the whistle at the mill too. When she gives her father his pail and ajar of cool, fresh buttermilk, he gives her a penny to buy jaw breakers or licorice.

“Jump up, now, ” Ida’s mother is saying.

But it is Nancy’s hands pulling her up.

“Mamma, please help a little bit,” she is saying.

Ida tries to push up with her left hand.

“That’s it, Mamma. Almost,” Nancy coaxes.

Nancy is pulling and coaxing and pulling. Ida’s hand slips as Nancy pulls her to her feet.

“Now what were you thinking? For Christ’s sake!”

“Don’t blaspheme,” Ida says.

“Getting on that chair and into the sink for goodness sake!” Nancy waits, rubbing her hands up and down the legs of her jeans and the backs of her arms, straightening her short brown curled hair. Nancy is in her early forties. Her blue eyes have deep dark circles under them. She reaches for her mother’s arm.

“Let me see.” Ida closes her eyes and tightens her mouth. Something about a man in a yellow hat, she thinks. “Humph,” she says, turning back toward the sink and pointing out the window, her tremor growing more exaggerated. “There’s a man digging holes in my yard. I tried to see who he was, but he moved past the snowball bush.” Ida looks hard at Nancy, irritated. “So I climbed up to see if I could get a better look.”

Ida jerks her arm away from Nancy and swats at her. Hedge should be here to see about this. Ida puts her right hand to her head, and her thumb and forefinger begin separating and spreading across her eyebrows. Over and over she rubs them. Her voice becomes shaky. She sits in one of the turquoise dinette chairs by the table.

“Then you, you come along and scared the hell out of me. Here, get me some buttermilk.” Ida takes a glass from the table and holds it in front of Nancy.

When Nancy sets the buttermilk in front of Ida she smoothes the red and white oil cloth, and she points out the window again. “Child, you go tell that fellow that he must have it wrong. This is the Hedgecock place. He best fill in those holes he’s dug and get on to his rightful place before Mr. Hedgecock catches him.”

“It’s Fred out there, Mamma. He’s just digging post holes. He knows what he’s doing.”

“Well, I don’t! Mr. Hedgecock don’t!” Ida’s arm moves up and down, in and out, first pointing to herself then to nothing. “And who the hell is Fred? I don’t remember Hedge saying nothing about no post holes nor no Fred. He tells me these kinds of things you know.” Ida’s tremor begins to worsen again.

“Okay, Mamma. Just calm down.” Nancy holds Ida’s shoulders. “We don’t know what else to do.”

Nancy’s face is so pained that Ida becomes more uneasy. Where is Hedge? She can’t count on him at all lately, and it just ain’t like him. She can’t remember asking for post holes. She has a little white fence with a gate that Hedge put up when her mamma died and left the house to the two of them. He was so proud to have a place of their own. Hedge loves this place and he has made a fine home for Ida. He has always been a homebody. But now days he comes to the door and walks through the house and says some little something he’s said a million times before, and then he leaves. Just like that. It beats all get-out to her that he can leave her out to dry that way. After all these years together.

Ida looked all over for him yesterday. Spent the whole day looking for him before she spotted him heading for the river. He hadn’t been home to sleep in his own bed in so long she could hardly remember when.

He better get home and take care of things, she thinks, or there will be holes all in his yard, and he’ll step in one and break his neck. Not that it wouldn’t serve him right. Tears roll down Ida’s face.

“Mother don’t cry.” Nancy searches her sweater pockets for a tissue. She refolds the tissue she finds and wipes Ida’s eyes.

“Hedge won’t come home to bed or chase this Fred man off our land. And I hate that gun. I don’t like to use it, and he knows it.” Ida’s lip quivers as she nervously rubs her fingers against the sweat on the glass of buttermilk.

“Lord, Mamma, I wish you would get it in your head that Daddy is dead. And Fred, you know Fred. You love Fred.”

Ida nods her head and cries quietly between sips of buttermilk.

Ethel walks outside. It must be Ethel, she is always upset about something, always thinking she’s been slighted. Ida is confused about things. Things she ought not be confused about. Like whether it’s her turn to take Pa his dinner at the hosiery mill. Seems like Ethel took it last, maybe not. Ida can’t find her mother to ask her. Ethel keeps saying it’s all history. But Pa will want his buttermilk, history or no. And Pa can be a hard man when he’s angry. Ethel ought to know that.

Ida gets up from the table and walks to the icebox. Her right leg and hip are hurting for some reason. She puts cold fried chicken and quick biscuits in a paper sack and reaches for a jar for Pa’s buttermilk.

Things go white again and in a minute they’re normal. Ida can hear Fred chucking away at the hard clay near the back door, yet she doesn’t really hear it.

When Ida finally makes it outside it’s dark. She has a hard time getting out the door. She walks a few feet until she runs into something, and she can’t go any farther. She sits down on the ground by a fence. It must be a mill fence. She leans back into the chain links, shining in the moonlight, and waits for the whistle.

That Hedgecock boy is standing by a mulberry tree. He’s watching her. He’s good looking, and she knows he’s soft-spoken and good-hearted. He sat with her at the church picnic back in spring and came with his daddy to buy a cow last month. She knew he was watching her hang clothes on the line, but she didn’t look back. He makes a good dance partner too. She’s seen that. And he likes her all right. But she is tired of waiting for him to make his move.

“You just gonna stand back and gawk at me?” she says.

“Nope.” He comes closer, and she offers him her smooth white hand and he helps her to her feet.

“Well, what are you gonna do? ” she says.

“You’ll see, ” he says.

Ida wakes up and squints into a bright morning sun. Her neck and bottom hurt and her knees are stiff. She works hard to straighten her legs, and notices that the mill fence is much closer to her house than it should be. She thinks maybe she is dreaming. Her faded blue gown is damp with dew.

The dark-haired woman comes out the back door. For a minute Ida thinks it is Ethel, but then she remembers Ethel is dead.

Nancy walks over to Ida and slides down the fence and sits on the ground. Nancy takes one of Ida’s hands into her own and slides the loose spotted skin around over the prominent bones and veins of the old hand. For a moment, only a few seconds, Ida recognizes her yard and sees that the fence is not the mill fence. She knows she should recognize the woman who is staring at her old tough hand, making little ridges with the skin and then smoothing them away. But Ida cannot come back that far.

Ida puts her free hand on top of the younger woman’s and says to her in a loud voice, “Hey, honey. Have I told you I had a good husband and two pretty babies once? I don’t know what happened to them anymore, but once upon a time I used to have everything I wanted.”

Nancy stands up and helps Ida to her feet. The two women go into the kitchen for breakfast.

Tags

Darnell Arnoult

Darnell Arnoult grew up in Henry County, Virginia and now works for the Center for Documentary Studies in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)