This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

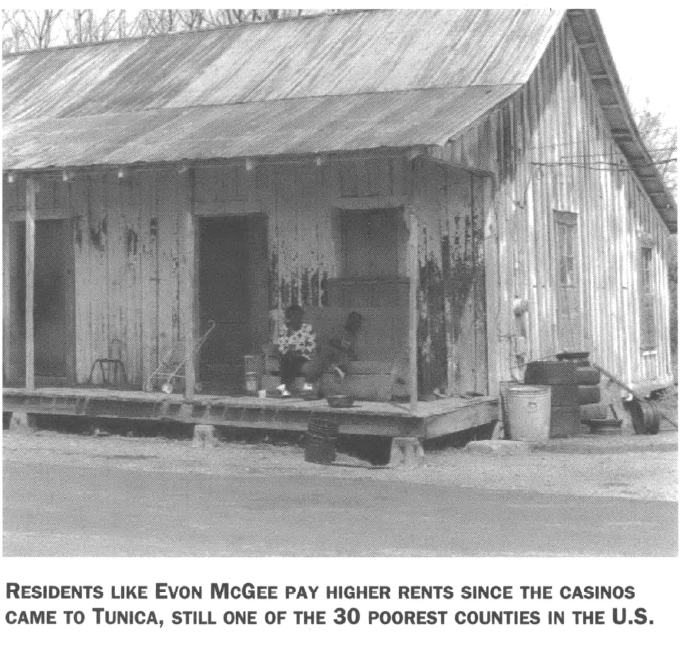

Tunica, Miss. — Evon McGee has fresh tar on her street, but she still has tarpaper on the walls of her home.

McGee and her two children live in a rotting wooden house in a poor neighborhood called “the old subdivision.” Her street was paved recently, thanks to millions in tax revenues generated by six riverboat casinos. The barges float in ringed-off pools on the Mississippi River seven miles outside of town, their decks overflowing with weekend gamblers from Memphis and Nashville, Little Rock and Birmingham.

Unfortunately, few of the coins that tourists drop in the slot machines find their way back to local residents like McGee. She can’t get a job on the riverboats because she doesn’t own a car, and no buses run from her neighborhood to the casinos. Since the riverboats dropped anchor two years ago, her rent has jumped by 22 percent — an extra expense she can barely afford on her fixed monthly income of $605 in welfare and food stamps.

“I’m barely keeping food for the kids,” she says. “But we make do.”

Mississippi has gone gangbusters after riverboats since 1990, when it became the first of six states to approve waterfront gambling. With a low wagering tax, lax regulation, and no limit on the number of boats, Mississippi now ranks second only to Nevada for the most casinos in the nation.

“Mississippi’s whole philosophy has been we’ll let anyone in who’s honest and let the best people survive,” says Larry Pearson, publisher of Riverboat Gaming Report, a casino industry newsletter.

Pearson and other gambling proponents say the casinos bring jobs, tourists, and tax revenues to the cash-strapped state. But the flotilla of boats also brings a fleet of problems.

Cities like Tunica deluged with boats spend hundreds of thousands of dollars on road, water, and sewer improvements that aren’t funded by casino dollars. Small-town merchants watch in frustration as tourists spend most of their time and money on the boats. And in a black-majority county that ranks among the 30 poorest in the nation, the casino boom has raised rents, created a housing shortage, and done little to raise the standard of living.

“We still have poverty,” says Calvin Norwood, president of the Tunica County chapter of the NAACP. “All the money from casinos is going for new roads.”

Charles Dawson, a fellow NAACP member, is more blunt. “The casinos haven’t done anything,” he says. “They haven’t done nothing for nobody.”

Nevada Vaults

Southern gamblers have always found plenty of ways to lose their hard-earned money. Riverboats have sailed the Mississippi since the 1830s, and bets have long been placed at horse races, dog tracks, cock fights, county fairs, itinerant carnivals, and crap shoots.

In recent years, more and more Southern states struggling to make ends meet have looked to legalized gambling to help pay the bills. Georgia expects to rake in a record $1.1 billion in the first year of its state-sponsored lottery, and Louisiana has upped the ante with video poker machines.

Mississippi has led the way with riverboat gambling. After two years, the state already boasts two dozen riverboats — more than half the nation’s total — and the number could reach 41 by the end of the year.

Louisiana has four boats open for business, with more on the way, and other Southern states and Indian reservations may soon follow. A Dallas corporation has hired high-powered lobbyists to persuade South Carolina legislators to legalize casinos, and several Memphis officials want to sell Mud Island to a Native American tribe as a gambling resort.

“Texas and Florida will be the best markets,” says Daniel Davila, a gaming analyst with JW Charles Securities in Boca Raton, Florida. “Look at the demographics — especially in Florida, where there’s a lot of disposable income with the elderly population.”

Despite the conservative religious streak in the South, riverboats have failed to conjure up the Sodom and Gomorrah images of land-based casinos. “The American people — and I don’t know why they decided this — think casino gambling on a boat is not as evil as on land,” says Larry Pearson of Riverboat Gaming Report.

In Mississippi, most of the riverboats aren’t even boats. The casinos are generally built on floating barges which remain dockside, allowing gamblers to come and go as they please. The state has lured casinos by allowing them to remain open 24 hours a day, and by offering a bargain-basement wagering tax of eight percent, compared to 20 percent in most other states.

Many say the low tax rate cheats the public out of its fair share of gambling profits. “Any state that’s charging less than a 50 percent straight tax rate on all legalized gambling activities is a naive government,” says John Kindt, professor of commerce and legal policy at the University of Illinois.

Even so, the cash is pouring into state and county coffers. According to the Mississippi State Tax Commission, the state has collected $98 million in tax revenues and local governments have garnered $33 million since the first riverboat license was issued in July 1992.

But critics say that even larger volumes of cash are being washed away like silt down the Mississippi River. In the end, most of the riverboat money winds up in the vaults of Nevada casino giants like Lady Luck, Bally’s, and Ameristar.

“No wealth is added to the community because you have Las Vegas people running the boats,” says William Thompson, professor of public administration at the University of Nevada. “You’re exporting the bulk of the money back to Las Vegas.”

“Hurts So Good”

Nobody understands the elusive nature of casino money better than Tunica Mayor Bobby Williams. The riverboats flooded Tunica County with $5 million in taxes last year — and this year the payoff should reach $13 million. Before the casinos opened, the entire county budget was $3.5 million.

But the city of Tunica doesn’t get a dime. Since the boats are in the county — outside city limits — the money stays in the county. Yet the city has been forced to increase its spending to handle the crime, fire, and sewage generated by the boats.

“Casinos are tearing us up, they’re costing us money,” Williams says. “But it hurts so good.”

The good: People are working. Since the boats arrived, the mayor says, jobs are plentiful. Local unemployment dropped from 26 percent in 1992 to less than five percent during the first quarter of this year.

The bad: The city police department budget increased $70,000 this year — a leap of 50 percent. The town of 2,000 also needs a new city hall that will cost taxpayers $700,000.

“Before the boats, all we worried about was getting the mosquitoes killed in the spring and the garbage picked up,” says the mayor. “Now we got sewage problems, we need a bigger police department, and we have to pay some volunteer firefighters.”

A few casinos have given money to the city. Two oversize checks from the boats Splash and Lady Luck — each for $ 100,000 — adorn the walls of the mayor’s office. But neither that money nor inconsistent contributions of $10,000 from all the boats to a fire fund are enough to pay for new equipment the fire department needs should a riverboat go up in flames.

“I think boat owners are a little ticked because we haven’t hired any more firemen,” Williams says. “But how can we if we don’t have the money?”

As local business has picked up, the city has received some money from increased sales taxes. Retail sales jumped by 50 percent during the first year the boats opened, generating more than $8,000 in revenues. Most of that money has gone to strengthen police protection.

Still, local officials complain that most of the business goes elsewhere. A few new restaurants have opened in town, but almost all the new motels are outside the city limits — and thus outside the reach of city sales taxes.

Area residents “are making good money, but they’re spending it in Memphis and Desota County” north of Tunica, says Webster Franklin, director of the county Chamber of Commerce. “So Tunica County isn’t reaping the benefits from retail sales.”

Not Casino Rich

“”

The Blue & White Restaurant, popular for its meat and gravy dishes, has seen business double since the boats docked. Wiley Chambers, owner of the Blue & White since 1972, has doubled his seating capacity. Business seems brisk — until he sits down and scrutinizes his books.

“We’re making a little more, but the overhead has increased quite a bit,” he says. “We’re not making a lot. We’re not casino rich.”

While business in Tunica has not exactly boomed, residents have been stunned by how quickly the cost of living has soared. When Yvonne Woods was transferred to Tunica a year ago to manage the T-W-L variety store on Main Street, the cheapest house she could find in a neighborhood she liked cost $400 a month.

“I couldn’t find a place to live because the rent was so high,” Woods says. So each day she commutes a half hour to Tunica from Helena, Arkansas, where she can afford her $225 monthly rent.

Seven miles from Tunica, near the grassy levy that separates the riverboats from the cotton fields, stands a new, drab-gray trailer park with about 40 units. Robbie Alderson and his wife Laura have lived in the complex since Robbie came to work for a casino construction company six months ago. For their three-room trailer near a bog, they shell out $550 a month.

“I think it’s way too much for a trailer,” Laura says — especially considering the couple pays an extra $50 a month for a wall that divides the back bedroom into two rooms. “It’s kind of cheating that way.”

Property values in Tunica have also skyrocketed. In 1992, an acre of land in the county sold for an average of $250. Last year, the average going price was $25,000.

Casinos dismiss such gloomy economic side effects, insisting that riverboats create jobs, and jobs boost the local economy. Harrah’s casino, which opened six months ago, lists its economic contribution on a fact sheet: up to 3,000 customers daily, 900 local jobs, and an annual payroll of more than $12 million.

Steven Rittvo, president of New Orleans-based Urban Systems Inc. and a leading gaming consultant, insists that 75 percent of all riverboat jobs are new. “What about the construction jobs the boats create?” he asks. “Those are all new.”

But economics professors nationwide argue almost unanimously that casinos create few new jobs. With residents dropping their money at blackjack and poker tables, consumers actually spend less at area stores.

“Jobs are lost because dollars are drained from a scattered area,” says Earl Grinols, economics professor at the University of Illinois. “It’s a person laid off at Wal-Mart; it’s a waitress working three-quarters time instead of full-time; or a restaurant that didn’t expand because of the riverboat.”

John Kindt, the commerce professor at Illinois, agrees. “It’s not true to say this is economic development,” he explains. “For legislators to look to it as a quick fix — for tax dollars up front — is poor legal policy.”

Some Southern officials also doubt the wisdom of building an economy on slot machines. “A lot of states have hooked their economies to gambling revenue, funding everything out of lotteries and casinos,” says South Carolina Governor Carroll Campbell. “Then all of a sudden they go down, and the state is stuck.”

High Wages, High Skirts

Tunica County remains ferociously poor — annual income is less than $6,500 per person — and residents who have found jobs aboard the riverboats are glad to have them. Gale Williams, 22, had never worked before she signed up as a food server and hostess at Splash. She earns $5.50 an hour — enough to move out of her parents’ home into her own place.

“It’s helped me get a lot of things I couldn’t get,” says Williams. “I have a place to live, clothes, and I can pay my bills.”

Williams wears a typical white restaurant cook outfit, but other riverboat employees sport vastly different attire. Kimberly Koehler, a cocktail waitress at Splash, wears shimmery skin-colored hose, a black leotard, black shoes, and a short-waisted tuxedo top. The emphasis is on leg exposure.

“I hate the outfit,” Koehler says. “I had dreams I was a penguin and trapped under ice when I first started here.”

Koehler is paid $2.13 an hour but collects about $100 a day in tips. Her monthly take of $2,000 finances her sculpture work in bronze, marble, and aluminum.

The dress code bothers her, but it’s no different at the other boats. “It’s either a low-cut bustline or a high-cut skirt,” says Koehler, a Memphis resident. “It’s very sexist. I’ve gotten used to men looking at me like I’m a piece of meat. And 10 times a day I get told I’m the most beautiful woman in the world.”

The casinos encourage more than leering. Russell King, who earns $8.50 an hour as a cage cashier at Bally’s, often cashes paychecks for employees at other boats — and then watches as they spend it all drinking and gambling.

Both Koehler and King say there’s a serious alcohol problem among riverboat workers. Since employees are forbidden to gamble on the boats where they work, they go to other boats when they finish their shifts.

All the drinks on the boats are free — and alcohol has its effects. “One guy saw two dealers come over from another boat and they lost all their paycheck money,” King says.

King isn’t worried about losing his wages at the tables, but he is worried about losing his life. At night when he finishes work, he drives 27 miles north to Memphis on Highway 61. As many as 10,000 cars travel the two-lane road each day — a staggering number in a county of 8,000 people.

Local residents consider the route a highway of death. According to state records, 18 motorists have died on Highway 61 in the two years since the casinos opened — compared to 20 in the preceding five years. In April, the state transportation department announced it would expand Highway 61 to four lanes, but the project won’t be completed for three years.

“They’re scraping them off that highway all the time,” says Bud Lane, a Tunica store owner. “If you’re driving the speed limit, you know you’re going to get killed from behind. I try to go with the flow.”

With two more riverboats scheduled to open this year, the flow of local traffic has been increased by casinos competing for business. Splash buses gamblers from far-away spots, offering free round-trip charters and free buffet meals for tourists from neighboring Alabama, Arkansas, and Tennessee. The riverboat even took to the air this spring. “We have flights from Atlanta daily for $99,” says Rebekah Alperin, marketing director for Splash.

Yet for all the outreach, 65 percent of riverboat gamblers come from Memphis. “Tunica is trying to draw on Memphis, and it’s not in the numbers,” says Daniel Davila, the Florida gaming analyst with JW Charles Securities. “Almost everything going on there is just horrifying.”

“Playing Catch-Up”

State regulators don’t really have any way of knowing what’s going on at the riverboats. The statewide growth in casinos has overburdened the enforcement division of the Mississippi Gaming Commission.

“We’re barely keeping our heads above water,” says J. Ledbetter, chief of gaming enforcement. “It concerns me very much. We can’t do anything pro-active and at times we’re barely keeping pace. I’m sure there’s stuff getting overlooked because I don’t have the manpower.”

Ledbetter has only 10 agents in the field to police some two dozen casinos operating around the clock. By contrast, New Jersey has 175 investigators for 12 casinos.

The commission will add 36 more agents in July. But until then, the small staff will continue logging plenty of overtime double-checking weekly casino reports and reading computer tapes on slot machines.

“The problem was the industry took off and ran and we’ve been playing catch-up ever since,” says Ledbetter. “That’s not the way to do it.”

The lack of regulation suits the riverboats just fine. Mississippi is the only state that does not require casinos to report their earnings by boat, permitting owners to conceal how much they make on slot machines and gaming tables, and how much the average customer loses.

“There’s going to be a lot more gambling in the United States,” says Dave Kehler, president of the Public Affairs Research Institute of New Jersey. “Policymakers need to know what’s going on as future policy unfolds.”

All it takes to license a floating casino in the state is to park a boat in any puddle of water along the Mississippi River or Gulf Coast. “Some of these tributaries are questionable,” says Klaus Meyer- Arendt, associate professor of geography at Mississippi State University in Starkville. “Some boats are in a ditch with a pipe so they have water exchange.”

In Tunica, only one of the six casinos is a real boat. Lady Luck is nothing more than a plain square structure atop a barge, painted institutional green with a vivid purple front. Southern Belle, with its Roman-arch windows and huge staircases, resembles a large plantation mansion. Harrah’s looks like any luxury hotel.

Splash, nearly two football fields in length, is pastel pink with walls of nouveau-California stucco. It sits in an aquamarine tub of water — a far cry from the muddy chocolate of the river. Rebekah Alperin, the marketing director, explains that the casino colors the water with a dye called “super blue.”

“It’s not toxic,” she says. “Plus, it goes with our semi-aquatic theme.”

House Rules

Casinos like Splash may be in the pink, but Calvin Norwood of the NAACP remains unimpressed by the rosy facade. Like other residents, he worries that the riverboats will simply sail away when the gambling money runs dry. “I’d rather see industry come in because I know they’d stay,” he says. “The boats can leave.”

Lady Luck isn’t leaving the county, but it is picking up and moving to a new spot. Riverboats in Iowa have pulled up anchor and sailed to more profitable locales.

While Norwood would prefer more stable forms of economic development like schools and factories, he acknowledges that the casinos have brought a measure of pride to Tunica. “The jobs have been good because they’ve lifted black folks’ spirits.”

Several storefronts have gotten face lifts as new businesses have come to town. There’s a Chinese restaurant on Highway 61 and the local Planters Bank plans to merge with First Tennessee Bank.

On the other hand, there are some new businesses that community leaders would prefer not to see. Two loan companies have set up shop in Tunica in recent months, profiting from the flow of casino dollars.

“They’re bad; they’re worse than the casinos,” says Mayor Williams. “They tear you up.”

Tower Loan of Jackson opened a Tunica branch last July. Tony Valasek, the local manager, acknowledges that the majority of his customers are county residents who work at the casinos. He refused to say what interest rates the finance company charges.

Norwood says too many residents know from bitter experience how the loan companies operate. “If you get $1, then you have to pay back $2 to those places.”

Norwood knows that most of what is going on in Tunica is beyond his control, but that doesn’t stop him from trying. The NAACP is pressuring the casinos to provide money for housing and education, but so far only one riverboat has responded — with a check for $1,000.

Sitting at a concrete checkerboard table in a grassy strip that runs down the middle of Main Street, Norwood ponders the rapid changes that have come to Tunica during the past two years. As he haphazardly moves some stones around the checkerboard, he ticks off a list of community needs. Affordable housing. Better education and health care. Stable economic development.

But Norwood and other Tunica residents can’t move casino chips and dollars like the stones on the checkerboard. Most of the players are in Las Vegas, and they control the game.

Tags

Jenny Labalme

Jenny Labalme photographed the 1982 Warren County protests as part of a documentary photography class she took while an undergraduate at Duke. She spent almost two decades working first as photojournalist for The North Carolina Independent (now Indy Week), and later as a journalist for the Mexico Journal, The Anniston Star, and The Indianapolis Star, and is currently the executive director of the Indianapolis Press Club Foundation.