Freeze

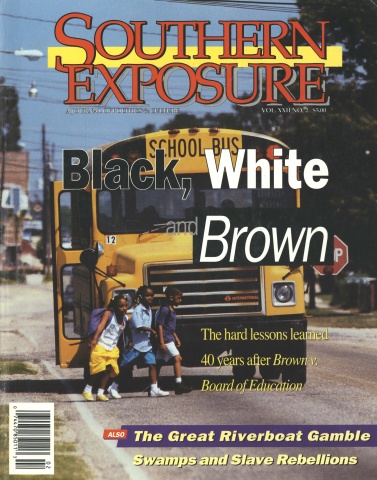

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

Last November, in the upstairs parlor of an elegant mansion blocks from the White House, I sat with Mieko Hattori, a mother and teacher from Nagoya, Japan. She’d just had a private meeting with President Clinton, who apologized to her from his heart. She’d been surrounded by media all day, and over the preceding year, millions had joined her crusade against American gun violence. She was accompanied by Mike Beard, the leader of the Coalition to Stop Gun Violence, the oldest gun control organization in the nation, who had been received in the White House for the first time in more than a decade. They brought with them millions of petition signatures and hundreds of thousands of letters. They also brought triumph — the same week Hattori came to the White House, the Brady Bill finally passed.

“What has been the most unexpected part of your visit ?” I asked her.

“I was so surprised by my son’s death,” Hattori told me, eyes wide, staring ahead. “Nothing can surprise me anymore.”

Her eldest son, Yoshi Hattori, was the exchange student who was shot in October 1992 in Baton Rouge, Louisiana when he went to the wrong house in search of a Halloween party. The killer was Rodney Peairs, a 31-year-old meat cutter at a Winn Dixie. Yoshi’s death touched a nerve in this nation: There have been Yoshi Days in several cities, scholarship programs have been launched, an article in Family Circle magazine generated an unprecedented number of letters, a quarter of a million Americans signed petitions against the easy availability of guns in Yoshi’s name, and the President said he was sorry more than once.

But early last summer, to the horror of the Japanese and the chagrin of many Americans, Rodney Peairs was acquitted of manslaughter in the 19th District Criminal Court in Baton Rouge.

No Urb

The trial in the case of The State of Louisiana vs. Rodney Peairs ran exactly one week, from a Monday morning straight through the weekend. The jury came in with its verdict a little after five Sunday afternoon. Outside the courthouse in the streets that day was a fair called “Fest-for-All” — there were stands for Chinese food, crawfish po’boys, and fried dough with powdered sugar. The music of blues and jazz ensembles floated by on a small breeze. The festival is one of several yearly attempts by city promoters to persuade householders to set foot downtown after business hours.

Baton Rouge once had a lively downtown shopping district, abandoned over the last 20 years because of the fear of crime, racial tensions, and the growth of suburbs. Back then, the city-parish was not as populous. In the ’60s and ’70s, the area experienced a boom in the petrochemical industry. Newcomers soon outnumbered the natives. According to Robb Forman Dew, a writer who grew up here, the quick expansion made Baton Rouge society more exclusionary, less “tolerant of eccentricities” than the average Southern town.

Now, after another boom in the early ’80s and a subsequent bust, the parish population tops 300,000. There’s still a concentration of office and government buildings downtown, including the State Capitol, filled from nine to five. Basically, though, the city is all suburb, no urb. Miles of brick ranchers and slab homes stretch away from downtown in every direction. The newer, fancier homes for the richest people are the farthest out. Some of the wealthiest citizens live in a guarded enclave full of French colonial plantation revival architecture in a southeast corner of the parish called “The Country Club of Louisiana.” Ads for the Country Club read, “We all remember a simpler time” — that is, a time that was safer, more predictable, and white.

Baton Rouge occupies one of the most heavily industrialized corridors on the continent. The white country people in the northern part of the parish arrived in the last generation to work for petrochemical giants like Exxon, which has a vast refinery along the Mississippi River. Some country people remained in the hamlets of Baker and Zachary during the booms, while the city surrounded them.

In the northeast quadrant of the city, in a predominantly white group of developments called Central, 12 miles from the oldest parts of Baton Rouge, is Brookside Drive and the brick ranch home where Rodney Peairs shot Hattori, a slender, smiling, eager 16-year-old boy who loved American dance and music. Peairs used an enormous gun, a .44 Magnum Smith and Wesson, called in the trade, a “hand cannon.”

On the evening of October 17, 1992, Yoshi and his host brother, Webb Haymaker, set out for a costume party for foreign exchange students. The host, seafood dealer Frank Pitre, had a girl at his house, Maki Iwasaki, from Tokyo. Yoshi wore a tuxedo, impersonating John Travolta in Saturday Night Fever. He and Webb headed toward the Central neighborhood. Finding a house decorated early for Halloween, they pulled up. They had transposed two numbers on the address. Pitre’s was a few doors down.

At the front door, they rang the bell. No answer right away. In a few seconds, they heard blinds rattling at a door from the rear of the carport which faced the street. Rounding the corner, the two saw Mrs. Bonnie Peairs, a short woman with glasses and frizzy hair, standing in the doorway. When Webb said, “Excuse me, is this?. . .” she slammed the door.

Walking away, confused, they heard Rodney Peairs opening the same carport door. Yoshi, apparently believing the first door slam was a mistake, or a Halloween joke, skipped back to the house from out by the street lamp, laughing.

Peairs, a pale man with a brown mustache, crouched in his doorway with his huge stainless steel gun. He shouted to Yoshi to “freeze.”

Webb, who couldn’t move as swiftly as Yoshi because his neck had recently been operated on, didn’t realize what Peairs had in his hands until he made it around the side of the cars in the drive. By the time he shouted at Yoshi to stop, it was too late: Peairs had shot Yoshi. Spinning around, Yoshi landed on his back not far from the threshold, gushing blood. Rodney, Bonnie behind him, backed inside, slamming the door.

Inside, Rodney could hear this boy moaning. As many times as he had shot a deer or rabbit, this was like nothing else. “It was like somebody else pulled the trigger,” his friend told me after the trial. Rodney put down his gun, went out back, and threw up.

Outside, Webb was screaming for help. Bonnie called 911.

Rodney came back inside again and took a seat at the kitchen table, where he’d been eating grits and sugar a few minutes before. While Yoshi died, Peairs put his head down and wept over his gun. “He’d been hit with a sledgehammer,” his friend said. “He couldn’t believe that what took place, took place.”

“Protecting My Family”

That Sunday in May, when word came that the verdict had been reached, the camera and sound men from nine networks — four American, five Japanese — came alive. For a week they’d been lingering in the heat, talking about how safe it was in Tokyo’s streets, how dangerous in New York, how dead in Baton Rouge.

Yoshi’s father, Masaichi, his translator Yoshinori Kamo, and Webb’s parents Richard and Holley Haymaker were locked out of the courtroom when the jury filed in — the space had filled with journalists and townspeople before they could be summoned. This lockout was symbolic of the way sentiment had been going locally and in the courtroom all week. The local TV news referred more than once to “the invasion” of the Japanese press, prompting some natives to side with the homeboy. Most Japanese attending the trial were resigned that Rodney would be exonerated from the start. “Yours is a society in decay, a resource to us, like India,” one told me during jury selection. “The Japanese won’t understand. In Japan, if someone’s killed, someone’s guilty.”

After jurors were let back in the box, the forewoman, a middle-aged white divorcee, stood to read “Not Guilty.” The jurors polled agreed. There were low groans, and loud cheers. The American correspondents rushed out, some with a look of disgust on their faces. The Japanese were slower to leave and better behaved, and a little stunned. “It’s very sad,” said Mori Towara, senior correspondent for the Mainichi Papers, “but we don’t say it’s wrong.”

The courtroom cheers, when reported in Japan, caused Mieko Hattori much pain at home. They came not from the Peairs family but, sources say, from supporters of his lawyer, Lewis Unglesby. A smart, blue-eyed man with expensive suits and a close associate of oft-indicted Governor Edwin Edwards, Unglesby had set out for a flashy win. When interviewed before the trial by a TV movie script writer, the defense attorney reportedly predicted that the only story in the courtroom “will be me.”

“What state do we live in?” Holley Haymaker, Yoshi’s American host mother, asked me upon hearing the verdict. A few tears formed in her bright green eyes as we entered an elevator to meet with Doug Moreau, the popular Republican district attorney who had just lost. Moreau’s a square shooter — dark plain suits and a pretty, graying Nick Nolte face. He wants to be governor. He’s already a god to many — he played football for LSU and the pros before becoming a powerful lawyer.

Holley knew the answer to her own question. She’s lived in Louisiana almost 20 years. A physician in family practice, she works with women, the indigent, and children at risk. She’s an activist, prochoice woman doctor, a rarity in South Louisiana. She and her husband Richard, a physicist, are idealistic, utilitarian, thoughtful people, not given to dramatics. Yet, when Rodney Peairs killed their charming temporary son Yoshi, they chose to try to add to the national discussion about Americans and guns. After scores of appearances on national TV shows and radio talk, they became gun control celebrities.

Their activism began in solidarity with the Hattoris, who started their movement — a petition to President Clinton about gun control — at their son’s funeral. Thanks to their ceaseless efforts and the constant attention they generated in Japan, the American media were unable to ignore what happened to Yoshi. Over and over, his death was used as a lead-in to the revelation that, among industrialized democracies, America is completely unique in its tolerance of guns. In Japan in a recent year there were 87 gun homicides. In the United States, 10,000.

In Baton Rouge, unfortunately, the gun-control activism by the Hattoris and Haymakers may have moved public opinion in favor of Rodney Peairs. The night Yoshi was shot, Richard and Holley were told of his death by phone. Arriving at the sheriff’s substation in Central about nine o’clock, they were met in the parking lot by Danny McCallister, a young officer who knew Holley from her work with rape victims. “This didn’t have to happen.” he told her. “There’s no excuse for something like this!”

While the Haymakers met with their son, McCallister and other officers questioned Peairs. To the investigators, Peairs seemed incoherent and unresponsive, as if in shock.

Peairs: My wife went to the door, and, uh, I don’t know whether she opened the door or she went to lock the door, but she hollered at me to go get the gun. So I ran. I didn’t ask questions. I reached in the top of my closet and pulled my suitcase down that I keep my gun in. And I opened it up, pulled it out and started for the front of the house. And, when I got there I didn’t see anything. I looked out the door. I didn’t see anybody.

Officer: You opened the door?

Peairs: I, I opened the door.

Officer: Was it locked?

Peairs: Un — I really don’t remember. It, uh, happened so fast I didn’t remember.

Officer: You opened the door and you didn’t see anything?

Peairs: I didn’t see anything at first, but then I saw something moving behind my pickup truck, to the right I mean, and a few seconds or split seconds later here comes this guy and it’s kind of hard for me to describe how he looked or dressed or . . .

Officer: Um, huh, do the best you can.

Peairs: He looked, he appeared to have a white suit and he was waving something in his hand, and saying something or appeared to be laughing, but he saw me standing there with the gun. And I had it pointed not at him but towards him and I told him to freeze. And he continued forward, seemed to speed up a little bit. And, and, uh, I guess I must have shot him.

Officer: You don’t know if you shot him or not?

Peairs: Uh, I, I must have, because he . . .

Officer: Did you say anything after you shot him?

Peairs: I, I don’t even remember.

Officer: You say anything to your wife?

Peairs: I just remember saying, “Why didn’t he stop, I told him to stop.”

Officer: Back when your wife told you to get the gun, what were you thinking? Do you know?

Peairs: I was protecting my family.

Officer: Did you know what you were protecting against?

Peairs: No sir, I didn’t.

Backdoor Neighbors

After making his statement, Peairs was not charged. Nor was he tested for drugs or alcohol; a source inside the department told me the station “screwed up” in that regard. The fact is, Rodney had been drinking that night, before the boys rang the bell. Although prosecutors presented no such evidence in court, the attorney representing the Hattoris in a civil suit scheduled for trial in September said Bonnie Peairs has offered a sworn deposition that her husband was drinking whiskey that evening.

At the time, investigators seem to have been confused about the facts and how to interpret them in light of Louisiana law. One factor was a famous “Halloween shooting” some years back in Baton Rouge, where two young boys in fatigues with fake machine guns startled a homeowner, who got out his real gun and shot one. The man, Robert Bouton, who lived in a subdivision not far from Peairs, was found innocent. His defense was that the “flash” on the toy gun startled him, and his gun “went off.”

There is a doctrine in Louisiana law that a person who brings on a difficulty cannot claim self-defense, or justifiable homicide. Bursting out of your own door with a huge gun, after no more provocation than the sound of a doorbell, and attracting two unarmed boys back from out by the curb, as Peairs did, might be considered “bringing on a difficulty.”

But Louisiana, like many states, also has a popular legal doctrine known as “Shoot the Burglar.” The law states that a homeowner can claim self-defense if he is inside his dwelling and he shoots an intruder.

Among whites like Peairs, from rural backgrounds, a carport is a substitute for a back porch, a feature lacking on the brick tract homes they live in now. Many entertain, cook, hold dances, and work in their carports.

Stan Lucky, who lives next door to Peairs, has a couch in his carport, and potted plants. It has the feel of a Florida sunroom with a car parked in it. Lucky told me his carport was part of his house, of course. I pointed out that his front door is completely blocked off — any stranger who wanted to see him would have to enter his carport to get to his door. As I stood there, not far from where Yoshi fell, Lucky declared his right to shoot me, should he discern I was an “intruder.” I saw myself toppling over, knocking down his spider plants in their wide yellow pots.

Lucky, who has an unlisted phone number, was not upset that his lack of any neutral ground put all strangers approaching his home in mortal danger. Country people have a saying, “Backdoor neighbors are the best kind.” Some, like Lucky, only have backdoors. Others, like Rodney and Bonnie Peairs, only answer their backdoors. Faced with the diversity of suburban and modern life, the assumption is, if they are strangers, they are enemies.

The morning after Yoshi died, officers decided to go back out to the scene of the crime and see what really happened. Once again they went over the events of the night before with Peairs; once again he was not charged. “There was no criminal intent,” Major Bud Connor of the sheriff’s department told the local paper.

Not everyone in the department supported that conclusion. Some of the younger detectives believed Peairs had committed murder. Frank Pitre, who was hosting the party for foreign exchange students, walked on the scene a few minutes after Yoshi was shot, in time to see the ambulance pull away. “As far as I’m concerned,” an officer told him, “Peairs is going to the electric chair.”

Later, during the trial, defense attorney Lewis Unglesby criticized officers who thought Peairs ought to do time. He pointed out that officers themselves have killed men in mistaken self defense — victims who later turned out to be unarmed. This happened twice in Baton Rouge in the year preceding Yoshi’s killing. In neither case — both involving innocent black males, one of whom was retarded — did the district attorney make an indictment.

Guns and Rain

On the Monday after the shooting, the Hattoris flew to Baton Rouge from Japan and met with the Japanese Consul in New Orleans. Later, the Consul met with Governor Edwin Edwards and District Attorney Moreau. Not long after, Moreau announced a grand jury investigation, which charged Peairs with manslaughter.

Unglesby was not shy about fueling the belief that the charge resulted from political pressure. “We all know what the Japanese want out of this case,” he said loudly in court during jury selection.

Potential jurors had mixed reactions to the shooting. Some seemed accustomed to teenagers dying from guns. “I don’t see what the big deal is,” said one, a black woman. “This happens all the time.”

Others were extremely upset. “I have children in this neighborhood,” said a white man who lived near Peairs. “Two teenagers who come and go. They have to be able to walk up to a guy’s door.” People who expressed such sentiments were dismissed.

Jurors could be forgiven if they confused the central legal question in the case — did Peairs shoot in self-defense, or did he bring the difficulty on himself — with advice given to some homeowners by local law enforcement officers. In 1983, my husband interrupted a robbery at our home in Baton Rouge. The burglary detective who came to the scene instructed us to go out that night and buy a gun. If the man came back to finish the job, he said, we should shoot him and drag the body into the house.

According to Richard Aborn, the head of Handgun Control Inc., officers in Baton Rouge are not the only authorities in “Shoot the Burglar” states that suggest such action. Sources in the Baton Rouge Sheriff’s Department say they no longer give out such instructions.

During jury selection, Moreau told me he was surprised so many potential jurors were against Peairs. He had bought the idea that Baton Rouge was overwhelmingly on Rodney’s side. Perhaps this was because of the success Unglesby had in instilling pity for his client in the popular press. No sooner had he taken on the case than Unglesby announced that Peairs wanted to tell the Hattoris how remorseful he was.

Close to the time of the trial, in a prominent Sunday feature in the Baton Rouge paper, Peairs came across as a simple man destroyed by the events of October 17th. He was a victim of the Japanese media who hounded him from his home, and of his employer, Winn Dixie, which asked him to take a leave of absence. He loved animals, it was emphasized: He was an overgrown 4-Her, not Dirty Harry. In the same interview, his father said that what people should learn from the shooting was that Webb and Yoshi were guilty of disobeying Rodney’s authority — they didn’t stop when the man with the gun said “Freeze.”

As a piece of propaganda, the interview was masterful. Those in Baton Rouge still confused by the case may have felt it was easier to hate the Japanese and professors and liberals like the Haymakers than to parse out the complexities of why and how what Peairs did was wrong. Since most residents also oppose “people taking our guns away,” they were unable to imagine how Peairs might have responded to his fear if he didn’t have a gun. To them, a society without guns is something impossible, like a society without, say, cars, or maybe even rain.

Besides, according to the paper, Peairs had an outpouring of support, throngs at his side — the bandwagon appeal. Actually, public opinion was divided. According to Connie Hardy, an office manager who answered the phone for Lewis Unglesby, calls against Peairs were even with calls in his favor. It was “like abortion,” she said — people were fierce in their feelings, for or against.

Hardy, a young white country woman who wears boots and wide buckles and speaks her mind, was convinced Peairs was a killer. The day after the verdict came in, she said, Unglesby accused her of “leaks” to unspecified parties and fired her.

Hunt the Pedestrian

The trial revealed that the ambivalences in the law are in people’s hearts. The prosecution focused on the first half of what Peairs did, his criminal behavior in the seconds before he pulled the trigger — asking no questions, getting his gun, coming out ready to fire, endangering himself, his wife, and two lost boys he attracted back into his carport. It was a case of shoot the burglar becoming hunt the pedestrian.

The defense focused on the second half of what Peairs did, his behavior in the moments after he picked up his gun — calling warnings to a stranger in an area he considered his domicile, and blasting when the stranger came toward him. This was harder to call in terms of what is justifiable homicide in Louisiana.

Unglesby made much of the fear Peairs felt — although he presented no evidence that the remote subdivision of Central was prone to violent crimes. He successfully put the blame everywhere else. He blamed Webb Haymaker, who has a slight stutter. (Why, Unglesby wondered, didn’t Webb simply approach Peairs and say, “Hey, y’all, no problem” like a Southern gentleman?) He blamed Webb’s parents, whom he portrayed as neglectful liberals. He blamed Bonnie Peairs, who took the rap on the stand with copious tears, saying, “I just didn’t think.” He even blamed Yoshi, who he claimed broke a “social compact” by coming right up and not pausing to give Peairs space. Unglesby blamed Yoshi because his eager movements were “erratic,” because he didn’t know that “a pointed gun is communication.” In this logic, Yoshi was guilty for being innocent of the terms of deadly force.

With the help of Nina Miller, a psychological consultant who helped with the jury selection in the Mike Tyson trial, Unglesby had rehearsed the case in a pair of mock trials. He was worried about certain aspects — the fact that the gun was so huge, the fact that “you could blame Bonnie, but since she wasn’t on trial, people might go after Rodney.” He thought he couldn’t have any women on the jury, but he learned that wasn’t so. And the fact that Yoshi was a 16-yearold boy, no problem.

Most of all, he wondered whether jurors could ignore the fatal outcome and just look at the shooting from Rodney’s point of view. He found some had no trouble identifying with the man who held the gun. “So I went into the courtroom with confidence,” Unglesby told me later.

During the trial a Baton Rouge reporter — the author of the Peairs-is-a-hero interview — found it unseemly that the prosecutor held up Yoshi’s dark brown blood-soaked tuxedo and gave it to the jury to inspect. He was not interested in putting his readers in the position of the wearer of those clothes, the dead Japanese boy. Much more comfortable, after all, to identify with Rodney, the man with the Magnum.

Guns are part of life in Baton Rouge, an absolute given. To blacks and whites I’ve talked to, a gun is a ritual object, like a talisman — it’s there to ward off danger, and because it’s there, you are blessedly safe. If there is an “intruder in your home” — or anywhere near it, apparently — you will exist at the end of the encounter, and he will not. It is righteous for you to do this blasting, but not righteous to have this blasting done to you. This fundamental appeal of the gun-selling industry is repeated by traders at the frequent Baton Rouge Gun and Knife Shows in the town’s civic center, by the media, and by the monthly magazine of the National Rifle Association.

According to the FBI, only 300 of the over 30,000 gun deaths in the United States every year involve someone killed while actually committing a felony. Thus, only 300 are “justifiable.” Overwhelmingly, people in this country use guns to kill people they know — friends, family members, or themselves. Sarah Brady, appearing with the Haymakers in Baton Rouge in July, spoke of the great embarrassment of the Peairs case around the world. She criticized the subtext of the increasingly popular “Shoot the Burglar” laws: Americans hold property more valuable than human life.

Still, many in Baton Rouge were confounded by the acquittal of Rodney Peairs. They couldn’t blame guns, or the law, or Yoshi — after all, he was an innocent, laughing boy. Something was clearly wrong. In a way, it would have been easier on people if Peairs had been guilty of something, if they could point to someone abnormal. They couldn’t.

Instead, they were left with a disturbing new interpretation of the Shoot the Burglar doctrine: Property owners may simply shoot anyone on their land, no questions asked.

“What about the plainclothes cop who runs across a person’s lawn after a criminal?” one sheriff’s department official asked me during the trial. “What about the UPS man? Is it getting to be you get scared, you come out blasting? I’ve been shot at by homeowners, trying to do my job. What happens to civil order?”

Beer and Barbarism

Throughout the trial and afterwards, the Hattoris remained compassionate. They blamed their son’s death on the presence of guns in homes. Peairs, they said at Yoshi’s memorial service, was a victim of his “gun culture.”

The evening the verdict was handed down, Masaichi Hattori talked with his wife in Nagoya. She tried to persuade him to take up Rodney Peairs on his offer to talk to them, to say privately those things that he had indicated publicly were in his heart.

The next morning the two families crossed paths at a local TV station. Bonnie Peairs initiated a conversation by pointing at Hattori. “I just want to know if he understands,” she began, to the astonishment of the translator. “If his boy had been an American, this wouldn’t have happened. Does he understand that? Does he?” The encounter was halted by Unglesby, the translator says, who started yelling profanities at him.

Leaving Hattori and the Haymakers after the trial that Sunday afternoon, I made my way through the army of newspeople. The stands at the Fest-for-All were beginning to close. The video cameras moved in on the two attorneys; others swarmed behind.

“I just want to get on with my life,” Peairs said, solemn and scared-looking. When asked if he’d shoot again, he said, “I doubt it.”

Japanese correspondents ventured into the crowds. A group of white boys in t-shirts, drinking beer, were asked by a Japanese woman in a blue linen suit how they felt about the verdict. One said, “Wonderful.”

At the same time, off to my side, Fuji television was catching a female medic parked at the edge of the festival, her ambulance on standby. “Not all Baton Rouge is like that,” she said. “How are we supposed to do our job? I have to go places at night, knock on unfamiliar doors. That’s my work. And what about our kids? How can anybody live like this?”

The next day, the editorial in the Japanese paper Asahi Shimbun would describe the “barbarism that is eroding American life.” That afternoon, the ambulance driver’s pleas were drowned out by the boys across the street, who began hooting cheers for Rodney.

Tags

Moira Crone

Moira Crone is a novelist and short story writer who teaches at Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. (1994)