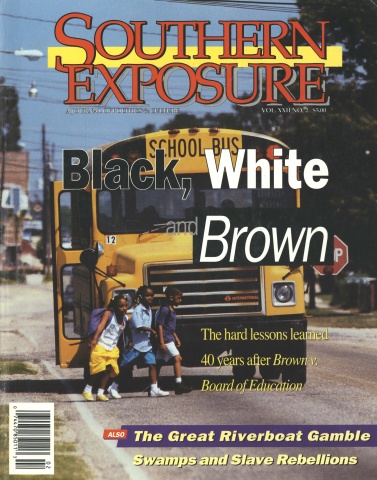

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

Sometimes the strangest things get connected in your mind. I’m sitting here reading the newspaper about Rodney King’s suit against the City of Los Angeles and it reminds me of James Brown with sweat dripping all down his hardworking, well-processed head singing, “If you don’t work, you don’t eat!” The old people would always tell us the same thing when I was growing up.

Nobody ever had to beg me to eat, so I took to work like a duck does to water. Fact of the business, I actually enjoy working — especially when it has to do with food. I figure that if I don’t like the job or the people I’m working with, I can always get plenty to eat.

I can do just about anything that there is to be done around a farm. Passing through Detroit a few years back, I worked on the Ford assembly line, and in Seattle I built airplanes for a while. I have raised skyscrapers in New York and drilled tunnels for the subway lines in San Francisco. I’ve been a cowboy and a merchant marine. I have covered the waterfront and then some.

One time, while traveling in Florida, I was almost out of money. Buddy, you don’t want to run out of money when you as much as fly over Florida. Florida deserves the reputation that they used to save for Mississippi. It wasn’t that long ago when Florida would put a black man up under the jail for dropping orange peels in the wrong waste basket. There’re some sections of Florida right now that you have to have a signed certificate from Jesus Christ and four other responsible white men just to pass through! And don’t get arrested! If you don’t have $10 to put down for a telephone deposit, you have to sign up for welfare and be approved before you can call your momma to tell her the shape you’re in. And you can forget about a lawyer . . . why do you think that those Haitian boat people have been stuck in those Florida jails for so long?

I was getting desperate for a job. I didn’t even have enough money to get a bus ticket to Waycross, Georgia. In a moment of weakness I signed up to take classes at the University of Florida. At the time they had all kinds of jobs you could get if you signed up to go to school. I was about 10 years older than most of the other students, but I loved to read and they guaranteed me a job, so I signed.

At first I was doing all right! I went to work for the student security patrol. We had uniforms and badges and everything, but no blackjacks or guns. I had never had a job like that and being that I loved to work so much, I looked at it as a new experience.

Our job was to do the things that the Campus Police didn’t want to do, as their job was to do the things that the regular police didn’t want to do. The two things I ended up doing the most of was guarding the Campus Lake in the evenings and on weekends I “guarded” the President’s Parking Lot.

The main thing at the Campus Lake was to walk around it two or three times in an evening to make sure there was no illegal sex going on in the nooks and crannies. Most of the time it was pretty uneventful work. The work at the President’s Parking Lot was pretty plain too, except on days when there was a football game.

I was beginning to enjoy my job and being a student. What I found out at that time is that college students don’t live in the same world that everyone else lives in. If I hadn’t been living in a cheap hotel in the middle of the black ghetto, it would have been easy to forget the conditions that ordinary people lived in.

Even so, it does not make me proud to tell you that just being on the campus all day every day soon got me to the point where I was beginning to see myself as “different” from ordinary people, in some ways even better than they were. Of course I didn’t think it was their fault — “they just didn’t have the same opportunities that the rest of us did.” If my grandmother had caught me looking like I had such an idea, she’da cuffed me upside the head and said, “If you take a fool and educate him, you ain’t got nothing but an educated fool.”

But Mamaw couldn’t help me get prepared for the fact that the main product of a certain kind of education is to make you act like a fool anyway.

It was a very prestigious thing to be assigned to work at the President’s Parking Lot, even if it wasn’t a football day. The President’s Parking Lot was right next door to the Office of the President of the University. All the big shots who had business with the President parked there. Occasionally there’d be other visitors too. But on non-football weekends the only people who tried to park there were graduate students on the way to the library or who worked in the theater, which was also nearby.

One Saturday afternoon, I was sitting in the call box guarding the empty parking lot. I was reading a very important book when this graduate student came speeding up.

I casually lifted my white gloved hand. I might have looked like the “Interlocketer” in a Minstrel Show. I just glanced up, expecting to smile and wave whoever it was through to the empty lot. But before I could see anything more than the graduate student sticker on his window, he gunned his motor and sped on through my post, with absolutely no regard for my authority!

I was pissed!

I slammed the book that I was reading down on the counter and took off running across the parking lot. I was definitely going to give this guy a piece of my mind. I ran after the speeding car, thinking, “This Dude has got his nerve! Wish I had a gun or at least a night stick. . . .”

All at once I felt like a character in one of those movie cartoons. It was like I stopped and stayed suspended in mid-air.

“What am I going to do with this guy when I catch him?” I thought. “I was going to let him park there anyway, so why am I doing this?”

The only reason I wanted to catch him, I had to admit, was because he had defied my authority. I could hear my Mamaw saying, “Ain’t you got nothing better to do? You’re just fattening frogs for snakes.”

I came down to the ground, turned around, and went back to my booth, packed up my things, went to headquarters, and turned in my badge that day.

I have often thought about how my life might have turned out if I’d had a gun or even a night stick that day to go along with my badge and uniform. I might have ended up like that gang of peace officers that beat up on Rodney King. The only reason they had to beat that poor man so bad was because they thought he had disrespected their authority. They probably still haven’t figured out that all they were doing was “fattening frogs for snakes.”

Tags

Junebug Jabbo Jones

Junebug Jabbo Jones sends along stories from his home in New Orleans through his good friend John O’Neal. (1994-1997)

John O'Neal

John O'Neal was a co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater for almost 20 years. He is currently touring the nation in his one-person play, Don't Start Me Talking Or I'll Tell Everything I Know: Sayings from the Life and Writings of Junebug Jabbo Jones. (1984)

John O ’Neal is co-founder and director of the Free Southern Theater in New Orleans. O’Neal’s one-person play, “Don’t Start Me to Talking Or I’ll Tell Everything I Know, ” is currently touring the country. (1981)