Community Clinics

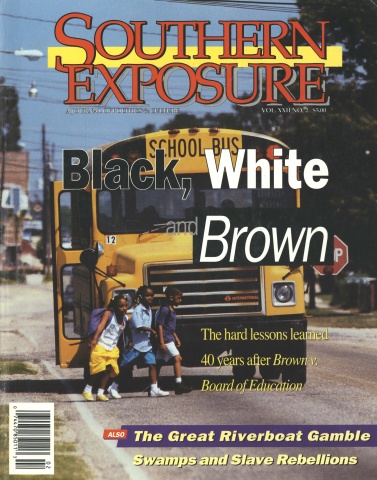

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

Underdevelopment and oppressive health conditions in the Black Belt magnify the depth of the national health care crisis. According to the Census Bureau, 40 percent of those with incomes below the poverty level live in the South. Low wages prevent many workers from paying the high premiums and deductibles of health insurance, leaving 13 million Southerners without coverage.

Health conditions in the region rank among the worst in the nation, in part because Southerners have the least access to health care. Most rural areas lack hospitals and clinics. The South has the fewest doctors per patient, and fewer still accept Medicaid or Medicare. Residents who can find and afford a doctor cannot make many appointments, since public transportation often consists of paying a neighbor $20 for a ride. To make matters worse, dismal health conditions are compounded by unsafe workplaces and toxic waste in Black Belt communities.

Since 1978, the North Carolina Student Rural Health Coalition has been working to improve health conditions and empower local citizens in rural communities. Working with the Community Health Collective, we have helped six rural communities set up their own “People’s Health Clinics.” In the absence of other health care facilities, the clinics provide free medical check-ups, health education, school physicals, occupational health surveys, and basic screening exams like pap smears, blood pressure, and cholesterol tests.

At each clinic, the goal is to empower individual community members to take charge of their own health. As one 91-year-old grandmother in Tillery said, setting up the clinic “gave me the feeling that I can do something to make changes in my life.”

A health committee in each community controls and organizes the monthly clinics. Initially staffed by members of the coalition, the communities themselves have gradually taken on more and more responsibility. We helped the committees start the first two clinics in 1987 in Tillery and Fremont. Since then, clinics have opened in Shiloh, Bloomer Hill, Garysburg, and Warsaw.

While all of the clinics were founded on the principle that everyone deserves equal access to quality health care, each grew out of a different community struggle. In Shiloh, for example, residents set up a clinic after years of pressuring federal regulators to clean up groundwater contamination.

In Warsaw, the clinic grew out of a workplace struggle at a textile plant that had closed down after injuring workers. “The owner had been taking money out of our checks to pay for health care,” says Pat Hines, a former worker who now chairs the Duplin Health Committee. “But we found out that he was not turning the money in to the insurance company, so we had no insurance.” The committee started by screening workers for occupational injuries, and now provides occupational exams at the monthly People’s Clinic.

Each committee developed its own goals and services for its clinic based on the needs of the community. Some conducted full-scale community health surveys, while others relied on committee members to identify local health problems. In most communities, heart disease and high blood pressure are major problems. In others, cancers or work-related injuries rank high.

To ensure that the services they provide are effective, the committees also identified barriers that prevent residents from receiving adequate care. Many cited no nearby doctors, no car, no medical insurance, no time off from work to visit a doctor, or racist attitudes among physicians and other health care providers.

Next came the question of where to house the clinics. The answer again varied from community to community. If a suitable facility already existed in the area, the community used it. For five years, Concerned Citizens of Tillery used their community center as a clinic building, transforming the kitchen into a lab and hanging sheets and using storage closets for exam rooms. The Bloomer Hill Health Committee used an old church and school, offering physical exams in former classrooms and bathrooms.

While hardly ideal, such buildings afforded free space to get started. Whatever the facility, though, the emphasis is on services, not aesthetics.

Medical supplies and equipment used in the clinics are also based on the needs of the community. If diabetes is a major problem, for instance, residents make sure that they can perform glucose tests in the clinics. If work-related injuries are common, educational materials from the Labor Department are made available.

Getting expensive medical supplies is not easy on shoestring budgets, but a little creativity and collective effort go a long way. Although most of the supplies are donated, clinic supporters raise additional money by selling refreshments in the lobby while patients wait to register, hawking raffle tickets, holding fish fries — even sponsoring gospel singing events.

Residents also try to be creative in publicizing the clinics, identifying the best way to spread the word in each community. Sometimes the coalition helps by leafleting homes in neighborhoods or factories where people work. Church announcements can be an effective means to pass on information, and many radio and television stations run public service announcements about the clinics.

The health committees recruit and train local residents, especially youth, to handle many of the routine tasks of running the clinics — registering patients, taking temperatures and other vital signs, and acting as clinic coordinators. They also help identify doctors, nurses, phlebotomists, nutritionists, and others who might be willing to help. Many health care providers agree to volunteer at the clinics twice a month or on weekends, while others offer to accept referrals. If they have a private practice, their liability coverage can be applied at the clinic as well.

To assist the professionals, the Student Rural Health Coalition recruits medical students from four participating universities — Duke, East Carolina, North Carolina Central, and the University of North Carolina. We take care to find people who are friendly and helpful, but we don’t leave their attitudes to chance. We also hold orientations for both students and health care providers. We teach them about the history, culture, and health problems of each community. We give them specific guidelines about how to be sensitive to differences in race, class, and language. We help them understand the people they are serving, and how to interact with them more effectively.

As a result, people who come into the clinics are treated with respect and dignity. Many patients say that for the first time in their lives, someone actually listens to their complaints without dismissing or downplaying them.

Sometimes that means going beyond specific medical problems to address social or personal issues. Clinic volunteers help patients with their taxes and explain simple medical terms that can be frightening. We realize that if people are worried about problems other than their health they are not likely to get well.

We found, for example, that one of the biggest obstacles for many rural residents is transportation. Offering free services at a clinic doesn’t mean much if a patient can’t get to the clinic. To address this need, the health committees organize car pools and enlist volunteers with cars to transport their neighbors to and from the clinics.

We know the People’s Clinics cannot cure the staggering range of health problems facing impoverished rural communities. But in areas that lack the most basic medical facilities, such clinics can have a significant impact.

Patients who need follow-up care use our network of doctors to find colleagues willing to take referrals from the clinics. Some laboratories offer discounts on tests, and the Community Health Collective has organized a program to provide discount medicines to senior citizens.

In essence, the People’s Clinics have become cornerstone institutions in these Black Belt communities. In Tillery, the clinic has outgrown its makeshift home in a sheet-draped community center. Residents have renovated an old potato curing barn as a permanent clinic and senior center. They call it the “Curin’ House.”

Above all, the clinics give people a sense of empowerment that comes from collectively taking control of their lives. “When I started with the health work, I was much more shy and not a leader,” explains Bessie Artis, chair of the Fremont Health Committee. “Now, through my involvement, I speak out and even run meetings.”

Thanks to the clinics, hundreds of residents like Artis have received basic health education and training in how to perform CPR, take blood pressure, and recognize the symptoms of various illnesses. Others have learned computer skills, navigated their way through Medicaid and Medicare, and studied proposals for health care reform. Workers organize forums on occupational injuries and diseases and receive free health screenings.

One of the most exciting programs to emerge from the clinics is the Pre-Health Career Internship, which encourages African-American students to pursue careers in health care and return to serve their communities. Students spend several days learning from experienced health care professionals at the four universities that participate in the Student Rural Health Coalition. The program not only helps students gain clinical and field experience, but also provides an environment that promotes social and community responsibility. One graduate of the program said it helped her decide to become a family doctor, since there were none in her community.

Through their work with the clinics, residents have also become empowered to tackle the politics of health care. In Fremont, local citizens demanded and won funding for the clinic from the town council. In Garysburg, members of the health committee helped defeat a proposed toxic waste incinerator. More recently, the clinics have served as a base for organizing support for single-payer national health care.

As medical costs continue to soar and reform proposals wind their way through Congress, “People’s Health Clinics” offer rural communities an immediate and powerful response to the health care crisis. By providing free care, the clinics can help reduce the number of people who needlessly suffer from preventable illness every year. By empowering rural citizens, the clinics can help lay the groundwork for a more just and humane health care system.

Tags

Jen Schradie

Jen Schradie is medical coordinator with the North Carolina Student Rural Health Coalition. (1994)