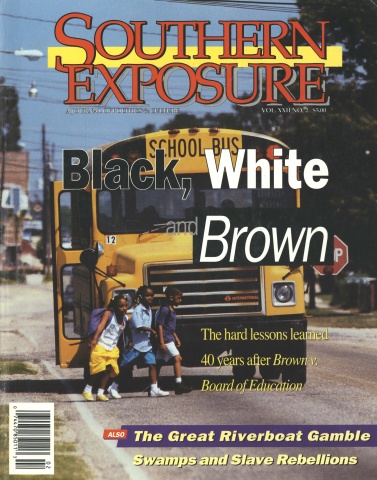

Black, White and Brown

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

It started with a school bus in Summerton, South Carolina. Black parents, tired of watching their children walk miles to school each day, sued the county for the same bus service white children enjoyed. Thurgood Marshall argued their case before the United States Supreme Court, and the justices unanimously struck down the Southern system of school segregation on May 17, 1954.

A lot has changed since the court issued its landmark ruling in Brown v. Board of Education. The decision helped spark the civil rights revolution and dismantle state-sanctioned apartheid. Despite massive white resistance, Southern schools in the region now rank among the most integrated in the nation. A study by the Harvard University Project on School Desegregation shows that 40 percent of Southern black children attend majority-white schools — up from none in 1954.

Unfortunately, much of the remarkable progress has been lost in all the media coverage of the 40th anniversary of Brown. Most stories have focused on the “failure” of school desegregation — how whites abandoned the public schools by fleeing to the suburbs or creating private academies for their children. Many have cited the Harvard study, which found that federal inaction has allowed schools to begin resegregating — producing another wave of poor, predominantly black schools that provide an inferior education.

“There have been some gains,” says Zepora Roberts, a black PTA leader and civil rights activist in DeKalb County, Georgia. “But for the most part, we have missed out.”

Whatever the successes and failures of Brown, however, its original intent should not be blamed for the mixed legacy of integration. Black parents who petitioned to end the myth of “separate but equal” enshrined by Plessy v. Ferguson in 1896 weren’t trying to eliminate the “separate” — they were trying to ensure the “equal.” Forcing schools to educate blacks and whites together, they felt, was one way to ensure equity. Desegregation was a means to an end — equal educational opportunities for all children — not an end unto itself.

The problem was, integration never involved a merging of equal partners. In practice, it resulted in the subordination of African-American education. Black schools were closed, their teachers and principals fired, their students assigned to white institutions that used color-coded policies like “tracking” to reserve the best teachers and classes for white children. In effect, integration ended black control of one of the community’s most important institutions, a place of empowerment and pride.

“There was never an integration of curriculum, of school boards,” says Leon Davis, a history professor at Emory University in Atlanta. “Primarily, the emphasis was on moving blacks into a situation with whites.”

Today, four decades later, many educators and activists are realizing that racial diversity was sacrificed in the struggle for racial equality. “None of the scholars or community people miss the age of segregation,” observes David Cecelski, a research fellow here at the Institute for Southern Studies, “but they recognize that something valuable was lost in the process of the great civil rights victory that integrated the public schools.”

To learn the lessons Brown has to offer, we return to the town where the struggle began — and where schools remain among the most segregated in the nation. We recount the history of one black community that fought to retain control of its schools, and we speak with a scholar researching the good qualities of black segregated schools in the South. We journey to Mississippi, where a community group strengthens black schools by drawing on the rich natural and human resources of the Delta, and where a new court case is expanding the struggle for educational equity.

Many Southerners fighting for school reform today focus not on integration, but on the educational needs of black children. Equality must be attained, they say — but not at the expense of diversity and democracy.

“Like most blacks, my disillusionment with Brown is not that it did not end school segregation, but that it did not make black educational attainment equal to that of whites,” says Isaiah Madison, executive director of the Institute. “To my mind, Brown did all that it could have done. It demonstrated that something more is needed to fulfill the substantive educational needs that have always been the primary goal of the black community.”

In short, we should not be too quick to give Brown a failing grade. True equality in education has yet to be tried, let alone achieved. After four decades in the classroom, integration gets an incomplete.

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.