Beyond Brown

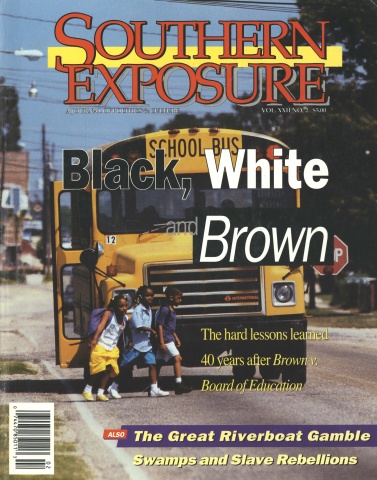

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains references to sexual assault.

On the last dat of April, more than 10,000 people gathered on the grounds of Jackson State University. They marched to the Masonic Temple, where they stopped for a prayer, and then moved on to stage a giant rally on the grounds of the state Capitol.

“Save Historically Black Colleges and Universities,” read one banner. “It’s about equity in education,” announced another.

It was a few weeks before the 40th anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education, the landmark case that struck down public school segregation in 1954. But the Mississippi marchers had a more recent Supreme Court ruling on their minds.

Two years ago, in its first sweeping decision on college segregation, the high court ruled in Ayers v. Fordice that Mississippi continues to operate a segregated system of state-run universities in violation of the U.S. Constitution. Ninety-nine percent of white college students in the state are enrolled at five historically white institutions, while 71 percent of the black students attend three historically black colleges.

African-American students and parents who filed Ayers in 1975 want Mississippi to upgrade black schools, where the state spends an average of $2,500 less per student each year than at white colleges. But the court remained silent on the issue of institutional enhancement for black universities, and instead left it up to the state to decide how to “educationally justify or eliminate” all traces of its dual system.

The state had its own idea of how to eliminate inequality. Arguing that it cannot afford to make each of its eight existing institutions equal, the State College Board announced in October 1992 that it would close historically black Mississippi Valley State University and merge predominantly black Alcorn State University and predominantly female Mississippi University for Women into larger, majority-white coeducational institutions.

The announcement hit alumni and supporters of the three universities like a bomb shell. Since then, African Americans and women across the state and nation have joined forces to save the schools. They staged the broad-based protest march in April, and less than a week later they took the fight to court.

On May 9, the case of Ayers resumed in U.S. District Court in Oxford, Mississippi. At issue is whose vision of the future of higher education will prevail. On one side are black students and parents who want to increase access for African Americans at historically white universities and upgrade historically black colleges into first-class, culturally diverse institutions. On the other side are predominantly white, male state leaders who are determined to eliminate or merge black colleges into larger, historically white institutions.

It is widely believed that Ayers will produce the most important judicial pronouncement of national educational policy since Brown. But focusing on the narrow legal controversy misses the real significance of the case. However it is resolved in court, the lawsuit has already sparked a resurgence in grassroots organizing as black Mississippians assume responsibility for securing equality in higher education. The struggle promises to have long-term political implications not just for Mississippi, but for the nation as a whole — particularly for areas in the South where communities of color comprise significant portions of the population.

“Ayers has put the subject of education on the lips of the common people in a way that has not existed in Mississippi since Brown,” says Leslie McLemore, professor of political science at Jackson State University. “Increasingly, Ayers is a focal point for discussion of a wide variety of important black-white issues.”

The Case

Few people understand the case and its importance as well as McLemore. In 1974, he helped organize the Black Mississippians’ Council on Higher Education to give leadership to the lawsuit.

“I remember all the community meetings we held in the early ’70s leading up to the filing of the case,” he says. “We were trying to fashion a theory for Ayers that would best serve the unique educational needs of black students. The case was designed to ensure that the desegregation of black higher education moves forward for the black community and not backwards.”

McLemore and others on the Council examined how successful historically black institutions had been in educating black students. They also evaluated the impact of school desegregation on black communities throughout the South — the massive closings and downgrading of formerly all-black schools, and the demotions and dismissals of black educators.

“We were shocked by the large numbers of black students being pushed out of the public schools,” McLemore recalls. “It was a result of student tracking, unfair discipline, the stigma of assignment to classes for the mentally and educationally retarded, and the discriminatory impact of standardized testing.”

Historically black universities must be preserved and enhanced, the Council concluded, to provide a strong education for black students and train a new generation of black leaders. “Thus, we decided to focus the Ayers case on both maximizing access to historically white universities and on upgrading historically black universities,” explains McLemore. “We felt this was necessary to prevent the black community from again suffering the kind of devastating educational losses it was already suffering on the elementary and secondary level.”

Victor McTeer, a lawyer who helped craft the legal theory for Ayers, emphasizes that enhancing predominantly black universities is a valid method of remedying the “historic pattern of discrimination” identified in Brown.

“The strategy employed in primary and secondary education to eliminate this pattern of discrimination was to close down the black schools and put blacks into the white schools,” McTeer says. “For the most part, that meant that whites left and enrolled in private institutions. We decided in Ayers that on the university level a more productive strategy would be simply to strengthen the African-American schools by giving them a fair share of the pie. Any resistance to this argument is race-based.”

Strengthening rather than closing black schools represented a bold new legal strategy in the fight for equal education. “We didn’t buy the theory that integration must always rest on the shoulders of black people,” says Hollis Watkins, a Mississippi organizer who helped develop Ayers. “It’s a responsibility of whites as well as blacks. The white leadership never talks about adequate funding for black institutions to make them attractive to whites. The argument that blacks want to preserve historically black universities as ‘exclusive black enclaves’ where they can discriminate against whites is just a smokescreen to divert attention away from the real truth of the matter — that we still have a lot of racism and discrimination in many white-controlled institutions.”

Watkins calls the proposed “merger” of Alcorn State and the Mississippi University for Women “a takeover on the part of the white male-dominated universities. Education should be made more accessible to students. Merging and closing institutions do not make education more accessible to blacks. In fact, it is more often than not used to prevent blacks from receiving a higher education.”

Clyda Rent, president of the Mississippi University for Women, agrees. “The Ayers case should not be about integration — doing away with segregation — but about providing learners in Mississippi with the best educational environment we can. Research shows that historically black universities do a disproportionately outstanding job of helping black people be successful. The same is true for majority-women institutions.”

A Democratic Resurgence

Supporters of black universities have little faith that Ayers will produce an outcome beneficial to the black community. The U.S. Supreme Court apparently rebuffed plaintiffs by refusing to order Mississippi to upgrade black colleges, and the white male leadership of the state has made its position all too clear.

Representative Bennie Thompson of Mississippi says he is “not optimistic” about the outcome of the lawsuit. “The remedy we offer is reasonable,” he told Black Issues in Higher Education. “But at this point, all indications tell me that Mississippi judges have a tough time ruling against their friends, church members, and golf partners when African Americans are involved.”

Accordingly, African Americans are looking beyond the courts to wage a long-term political struggle around the issues raised by Ayers. A national mobilization has been launched by the Black Mississippians’ Council on Higher Education, the NAACP, and a statewide student-led group called HBCU Watch that is organizing youth nationwide, educating the black community, and registering black voters.

“Students in historically black universities are beginning to get involved and express themselves in a way that is clearly related to the student activities of the early ’60s,” says Hollis Watkins, former activist with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee. “Then, students got involved in sit-ins because they were prohibited from going into many places that were open to the public. Closing some historically black institutions and putting others under the domination and control of historically white institutions is seen by today’s black students as a denial of their right to receive the best education and the education of their choice.”

Indeed, not since Governor Ross Barnett dispatched state police and white students went on an all-night rampage to prevent James Meredith from enrolling in the University of Mississippi have state-run universities been the focal point of so much public attention and political controversy. More important than the legalistic debate about the “educational justifiability” of maintaining racially identifiable institutions, the push to enhance historically black universities represents a growing demand by black Mississippians for meaningful involvement in decision-making about higher education.

“The Ayers case has unified and woke up black people and brought us back to our roots,” says the Reverend Eugene McLemore, pastor of Lynch Street CME Church of Jackson. “Going back to our roots always takes us back to our churches, our civil rights organizations, and our black political leaders.”

The case has also spurred women to mobilize politically. One of the most promising consequences of Ayers is the strong coalition being forged between blacks and women — an alliance that presents a powerful challenge to traditional white male dominance in Mississippi politics.

Lillie Blackmon-Sanders, an original plaintiff in Ayers and the first woman ever to serve as a circuit judge in the state, calls the decision to merge Mississippi University for Women (MUW) with male-dominated Mississippi State University “an act of an institution being dumped on because it is populated by women.”

“Like majority-black institutions, MUW presents an easier political target than the white male-dominated institutions,” she adds. “MUW has lots of programs that are unique from those of other state universities. There is no reason to stop funding them. It’s a power thing: The white male political hierarchy is determined to stay in charge.”

From Court to Ballots

In many respects, the current organizing around Ayers reverses a pattern among black Mississippians that dates back to their disenfranchisement following Reconstruction. Lacking proportionate political representation, African Americans have long depended primarily on the federal courts to protect and vindicate their legal and constitutional rights. But conservative judicial appointments by Republican presidents have made the courts less friendly to communities of color — and enforcement of the 1965 Voting Rights Act has begun to ensure serious black representation in Congress and the state legislature.

When Ayers was filed in 1975, only one black sat in the state legislature. Today, 42 of 174 state legislators are black — nearly one-fourth of the total. Over the same period, the number of African Americans in elected office throughout Mississippi increased from 192 to more than 751.

Given the increased political clout and increasingly hostile courts, Ayers may usher in a new era of “political litigation.” Unlike Brown, based on which the court seeks to definitively resolve substantive issues, activists are likely to use the court to focus debate and support negotiations in the political arena.

The political response by the black community has been given additional urgency by recent efforts to undercut electoral gains by African Americans. Next year, the governor plans to put a proposal on the ballot to reduce the state legislature to 50 members — less than one-third its present size.

Ben Jealous, field director of HBCU Watch, puts it bluntly: “We have to win the legislative downsizing issue in order to win Ayers.”

State Senator Johnnie Walls, an original member of the Black Mississippians’ Council on Higher Education, also recognizes the connection between the assaults on black legislators and black universities. “Depriving blacks of university education will limit the number of blacks capable of qualifying for powerful and influential positions in the state,” he says. “Limiting black legislative participation will seriously diminish the ability of black Mississippians to participate in high-level leadership and decision-making. It’s okay as long as blacks remain employees and under the direction and control of whites; but most whites can’t accept blacks being in positions where they have the final word. This is what the attacks on black universities and black legislators is fundamentally about.”

In the long run, says Walls, closing predominantly black universities will hurt democracy. “Whites know that closing black universities will diminish the ability of black Mississippians to be productive citizens and contribute to the state as a whole.”

From Domination to Diversity

During his visit to the United States, Alexis de Tocqueville took a ride down the Ohio River. On one side was Ohio, a free state; on the other was Kentucky, a slave state. On the Ohio side of the river, he observed much human enterprise: productive farms, industrious people pursuing numerous vocations — driven to achieve and contribute to society. On the Kentucky side, he witnessed pervasive dependency and unproductivity: slaves resigned to a virtually subhuman level of existence, living in abject poverty, whose work was half-hearted; and slave owners compensating for the meaninglessness of their lives by giving themselves excessively to sports, military exercises, and numerous violent activities — including abuse and rape of their slaves.

Mississippi once depended on a slave economy and still bears the material and psychic scars of its dehumanizing, debilitating past. Consequently, throughout the state can still be seen the lingering effects of its unenterprising, “colonial” heritage. Nowhere is the impact of this unfortunate legacy felt more painfully than in Mississippi’s continuing low educational achievement and widespread material poverty.

Mississippi would be a far more productive and hopeful place in which to live if its women and citizens of color were free to become all that they can be. This cannot happen as long as the traditional paternalistic order systematically assigns white men to the most prominent and powerful leadership positions, while characterizing blacks and women unwilling to accept subordinate assignments as “uppity,” “masculine,” or “out of their place.”

White male-dominated universities should not try to replace or “swallow up” historically black and women universities. Each of these institutions has a distinct educational function which it is best suited to serve. Black universities are depositories of the cultural memory and resilience of a people who in a little more than a century broke the back of chattel slavery, placed thousands of their kind in highly influential national and international positions, and made extraordinary contributions to the betterment of humankind.

There is no symbol more needed in Mississippi today than the triumphant emergence of African Americans from slavery to freedom. On this score, historically black universities have much to teach all Mississippians, regardless of race; and historically white universities — notwithstanding their obvious material advantages — have much to learn.

“It seems like the white leadership in Mississippi wants to keep black people unproductive, dependent, and satisfied with living at an almost slave level of existence,” says Robert Young, an original member of the Black Mississippians’ Council on Higher Education who teaches at Grambling State University in Louisiana. “They complain about blacks being on welfare while doing everything they can to keep blacks economically unproductive. The real tragedy is that they don’t seem to realize that when they keep blacks down, they also keep themselves down.” Young quotes Booker T. Washington: “You can’t keep a man in a ditch without staying in there with him.”

Plaintiffs and supporters of Ayers take issue with the declaration in Brown that “racially separated facilities are inherently unequal.” Instead, they have forged a broad-based consensus that the principal impediment to equal educational opportunity for blacks is not segregation but domination. They point to a recent meeting of white university presidents that excluded top black administrators as symptomatic of what is wrong with higher education in Mississippi. At the very heart of their demands is a simple request to be included in decisionmaking that affects their lives. Indeed, much of the frustration among black Mississippians over the threat to black colleges is rooted in their exclusion from the decision-making process.

A court-imposed “resolution” of the critical public issues in Ayers will only serve to exacerbate this pervasive sense among black students, alumni, university administrators, and public officials that they are being politically discounted. As long as white paternalism remains a vital force in Mississippi, blacks and women will continue to be outside the critical decision-making processes where substantive public issues, such as those raised by Ayers, are effectively resolved. This is why, particularly on the campuses of Mississippi’s predominantly black universities, a new Freedom Movement is struggling to be born.

“The black university is the cultural nurturer of African-American people,” says Robert Walker, a former mayor of Vicksburg who helped prepare Ayers. “The destruction of the black university leads to the destruction of the black community just as surely as night follows day. And since the uniqueness of the United States is its rich cultural diversity, the death of the black university — no less than the death of the Jewish, Irish Catholic, or Native American university — diminishes the cultural and spiritual vitality of us all. We Mississippians must celebrate our cultural diversity to create together a prosperous society.”

“Without a vision,” the saying goes, “the people perish.” The vision to keep black Mississippi colleges from perishing apparently does not exist in members of the State College Board or in the federal courts. But it clearly resides in abundance in the Ayers plaintiffs and those who have helped to develop and guide the case. They are well equipped to give leadership to creating a future in Mississippi big enough to accommodate all its peoples.

Tags

Isaiah Madison

Isaiah Madison is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies. He became interested in community economic development when working as a lawyer in Mississippi. He handled cases for black farmers having difficulties holding onto their land and became involved with the Federation for Southern Cooperatives. (1994)