This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No.2, "Black, White and Brown." Find more from that issue here.

Like chimneys standing in the cold ashes of a tragic fire, the old school buildings endure in rural communities across the South. A few have been reincarnated as textbook warehouses, old-age homes, or cut-and-sew factories. More commonly, though, they sit vacant and deteriorating in older black neighborhoods. People called them the “Negro schools” in the era of racial segregation, when millions of black children enlivened their classrooms.

As school desegregation swept through the region in the 1960s and 1970s, white Southern school leaders routinely shut down these black institutions, no matter how new or well located, and transferred their students to former white schools. No commemorative markers reveal what the black schools used to be, who once studied and taught in them, or why so many closed their doors a generation ago. Behind their weathered facades and boarded-up windows lies an important, hidden chapter in American history.

The mass closing of black schools was only part of a broader pattern of racism that marred school desegregation throughout the South. In its 1954 decision in Brown v. Board of Education, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially segregated public schools were unconstitutional, but the court left local school boards with the power to implement its ruling. Instead of reconciling black and white schools on equal terms, white leaders made school desegregation a one-way street. Black communities repeatedly had to sacrifice their leadership traditions, school cultures, and educational heritage for the other benefits of desegregation.

Throughout the South, school closings and mergers eliminated an entire generation of black principals. From 1963 to 1973, the number of black principals in North Carolina secondary schools plunged from 209 to only three. By decade’s end, not one of the 145 school districts in the state had a black superintendent, and 60 percent of those districts employed no black administrators.

The effect of school desegregation on black teachers was less severe but profound. An estimated 31,051 black teachers in the South were displaced by 1970. In a five-state survey, the U.S. Department of Health, Education, and Welfare (HEW) confirmed that between 1968 and 1971 alone, at least 1,000 black educators lost jobs while 5,000 white teachers were hired. The phenomenon was so widespread that in 1966, when New York City faced a severe teacher shortage, it developed Operation Reclaim specifically to recruit black teachers fired below the Mason-Dixon line.

Blacks lost important symbols of their educational heritage in this process. When black schools closed, their names, mascots, mottos, holidays, and traditions were sacrificed with them, while the students were transferred to historically white schools that retained those markers of cultural and racial identity. White officials frequently removed plaques or monuments that honored black leaders and hid from public view trophy cases featuring black sports teams and academic honorees. The depth of white resistance to sending their children to historically black schools was also reflected in the flames of the dozens of these schools that were put to the torch as desegregation approached.

For many black parents, desegregated schools too closely resembled former white schools in values, traditions, political sensibilities, and cultural orientation. In losing black educational leaders, they also felt deprived of an effective voice in their children’s education.

This educational climate and the loss of community control alienated some black citizens so thoroughly that they found it difficult to support the new schools. Many parents also observed a decline in student motivation, self-esteem, and academic performance. Racist treatment of black students within biracial schools only worsened an already difficult situation. Black students repeatedly encountered hostile attitudes, racial bias in student disciplining, segregated busing routes, unfair tracking into remedial and other lower-level classes, low academic expectations, and estrangement from extracurricular activities.

By 1966, few black communities failed to raise objections to school closings and teacher displacement. Black North Carolinians had organized several formal protests, and pressure on civil rights and political leaders for racial equality in school desegregation began to surge. Between 1968 and 1973, school boycotts, student walkouts, lawsuits, and other black protests challenging desegregation plans grew common at the Southern grassroots.

One of the strongest and most successful protests, the first to draw national attention to the problem, occurred in one of the South’s most remote and least populated counties. The school boycott in Hyde County, North Carolina in 1968 and 1969 signaled that black Southerners, in the words of an HEW official, “were tired of having to bear the burdens of school desegregation.”

“Something Belonging to Us”

For an entire year, black students in Hyde County refused to attend school. They did so to protest a HEW-approved desegregation plan that required closing O.A. Peay and Davis, the two historically black schools in this poor, rural community surrounded by swamps and coastal marshlands. Black citizens held nonviolent demonstrations almost daily for five months, marched twice on the state capitol in Raleigh, and organized alternative schools in their churches.

In the year after the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr., the school boycott became one of the most sustained and successful civil rights protests in the South. Though the size and resolve of black dissent was clearly exceptional, Hyde County was basically a microcosm of school desegregation throughout the region.

For Hyde County blacks in 1968, the O.A. Peay School embodied a rich educational heritage that dated back at least a century. Despite terrible underfunding, racial discrimination, and official neglect, black residents had conspired for five generations to create schools that fostered racial advancement and intellectual achievement. Teachers drew on the church and family to create a caring, supportive atmosphere insulated from Jim Crow. They set high standards for students, many of whose parents had almost no formal education, instilled in them a sense of social responsibility, and challenged them to further their education by attending college.

Hyde County blacks had never intended to sacrifice those achievements for the sake of school desegregation. They had hoped to merge their schools and way of schooling on equal terms with whites. Instead, white school leaders who had bitterly resisted desegregation since 1954 now succumbed to federal pressure and moved to control the terms of integration. With the approval of the state and HEW, they initiated plans to close Peay and Davis and transfer black students to the white Mattamuskeet School.

Excluded from the planning process, the black community was stunned. “They do not have the right to take something belonging to us,” said O.A. Peay alumnus Golden Mackey. When the school board refused to negotiate, the O.A. Peay School Alumni Association began organizing community opposition.

Joining forces with Hyde County churches, they formed a local leadership committee and contacted Golden Frinks and Milton Fitch, state leaders of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. With the support of the SCLC, they decided to boycott all county schools until white officials agreed to listen.

“We decided that they couldn’t implement their plan without students, so that we would boycott the schools until they . . . agreed to keep [our] schools open,” said Abell Fulford Jr., head of the leadership committee. “That was our goal: to keep the schools open no matter what. We wanted integration, but we would have taken anything so long as we still had our schools.”

On September 4, the first day of the academic year, only a handful of black parents sent their children to the Mattamuskeet School. Day after day, the boycotters held marches and mass meetings. An average of 150 to 200 demonstrators marched most afternoons from Job’s Chapel to the county courthouse in Swan Quarter.

The Children

Leaders of the school boycott realized that they needed to develop a “movement culture” in Hyde County that could sustain the protest through confrontations, threats, and the frustration of temporary defeats. To this end, they held community meetings almost nightly after the protest marches, rotating the location among the county churches.

Years later, participants still remembered the exhilaration and energy at those gatherings. Singing and worship formed the heart of every meeting. Visiting civil rights leaders frequently gave inspirational or educational speeches, and SCLC activists often conducted workshops on civil disobedience. “Everything was aired at the meetings," recalled Alice Spencer, a teenager at the time.

As the boycott continued, young people like Spencer assumed many of the day-to-day responsibilities for running the movement. Spencer and Charlie Beckworth kept the financial books for the entire operation, with help from two other young women. Ida Murray, in her early twenties, coordinated transportation. Linda Sue Gibbs, a teenager from Scranton, directed a choir that sang movement songs during meetings and protest activities.

By mid-October, more than 400 children attended “movement schools” organized in seven local churches. The schools offered an alternative education and a supervised environment, helping to build community unity and to strengthen the movement culture. The schools affirmed both the independent tradition of black education in Hyde County and the new sense of black pride emerging during the school boycott.

Black citizens, especially the children, developed a self-conscious awareness that they were living in an historic moment. They were determined that they would, in one’s words, “stand up once in our lifetimes.” The young people felt that Hyde County had never before had this extraordinary potential for social change, and they were afraid to let the moment slip away from them.

“If we do not do something now, it will never happen,” the children told Dr. Dudley Flood. He was impressed that “they had become convinced that they owed it to future generations.”

With this attitude, the young people threw themselves into the civil rights struggle, ignoring the risks and devoting every moment of every day to it. “You walked, talked, ate, thought . . . lived for the movement,” recalled Alice Spencer. “It was all you did.”

“I felt like I was giving myself completely to something larger and more important than myself,” recalled Thomas Whitaker, who would have been a senior at the O. A. Peay School that year. This awakened community spirit made them only more determined to hold onto their schools.

— D.C.

Despite the unprecedented revolt, the county board of education refused to negotiate, claiming that HEW was forcing them to close the black schools. In reality, officials were frightened and psychologically shaken by the boycott. They had been accustomed to having total power, and the mass protest had turned their world upside down. Farmworkers and oyster shuckers over whom they had exercised unchallenged authority had suddenly demanded a share of power and control over the schools.

“In private discussion you could physically see the fear in them,” recalled Dr. Dudley Flood, who served as one of Governor Robert Scott’s envoys to Hyde County. “They were so preoccupied with that fear that it began to skew the whole picture. Having what was right done was secondary to the encroachment on their power.”

“Tear This Place Down”

A county government agency sparked the protests that would draw national attention to the boycott. On November 1, nine weeks into the boycott, county welfare director W. A. Miller warned 31 families that the department would rescind benefits allotted for their school-age children if the children did not enroll in classes by December.

The idea that Miller would intimidate such vulnerable families appalled Hyde County blacks. On the afternoon of Friday, November 8, 150 young people occupied the county welfare office in Swan Quarter. Calling themselves “the Martin Luther King Crusaders,” the children informed officials that they would not vacate the building until Miller withdrew his warning. County and state law officers removed the demonstrators using Mace and tear gas, but the Crusaders continued the agitation across the street.

They renewed their protest on Veterans Day, the next Monday morning. At about 9:30 a.m., 24 young activists occupied School Superintendent Allen Bucklew’s office on the second floor of the courthouse and demanded a meeting with him. Outside, more than 100 students demonstrated and sang protest songs. Bucklew met briefly with the students at about two o’clock. When they again refused to leave the building, he asked law enforcement officers to evict them.

According to United Press International correspondent Jack Loftus, who witnessed the scene, Sheriff Cahoon and three state troopers wearing gas masks threw smoke and tear gas grenades into the second-story room of the courthouse and slammed the door, then held it shut for at least two minutes. Pandemonium broke out among the two dozen children trapped in the gas and smoke.

Some of the “young bulls” — in the words of a witness — managed to break out, but officers confined most of the children within the building. Many ran to the windows gasping for air. In the blind push of bodies, 17-year-old Mamie Harris fell or jumped out of a window. She broke her pelvis on hitting the ground two floors below and was rushed to the Beaufort County Hospital in Washington. Other protesters leapt more carefully and were not hurt.

The incident almost provoked a riot. “We ought to tear this place down,” teenager Jimmy Johnson cried out. When the tear gas cleared, several parents and children had restrained their angriest companions, but demonstrators still blocked every road through town. They pounded on cars and pleaded with state troopers to arrest them. Two girls lay across a car’s hood. Six teenage boys were finally arrested for impeding traffic — the first arrests in the 10-week-old school boycott.

The injury to Mamie Harris put the school boycott on the front page of the News and Observer for the first time. The Washington Post, the New York Times, and the major television networks immediately sent reporters and photographers to Hyde County. A correspondent from the British Broadcasting Corporation arrived within the week. Jet magazine and other black publications also sent reporters, and several school boycotters appeared on NBC’s The Today Show in New York City. The school boycott remained in the national news for the next two weeks.

The “Chicken Protest”

After Mamie Harris’s injury, school boycott leaders decided to organize demonstrations that would provoke arrests — enough arrests, they hoped, to overcrowd the small county jail and compel negotiations. Some 125 people marched the next day from Job’s Chapel to the courthouse; troopers arrested 52 who locked arms and blocked the highway.

The children crowded into the musty brick jail appeared “rather composed” to state troopers. They decorated their cells with pink curtains that afternoon and continued to laugh and sing “Ain’t gonna let no nightstick turn me around” while several dozen junior high-age youths stood outside the jail singing freedom songs. The jail was already so overcrowded that Sheriff Cahoon released the 30 girls that evening.

The school boycotters held more protests and provoked further arrests daily. Older black citizens demonstrated outside the county jail the next day in support of their children and grandchildren. When they marched back out of Swan Quarter toward Job’s Chapel, a smaller group of about 25 young people led by James “Little Brother” Topping, a teenager from Lake Landing, marched into town carrying chickens, a gesture that goaded law officers into arresting 18 of them. A 13-year-old rushed to catch up with her friends, calling out “Hey, wait for me, Mr. Trooper, I want to be arrested too!”

The day after the “chicken protest” — Thursday, November 14 — 30 to 40 teenagers conducted a demonstration by blocking traffic and tossing a basketball in the intersection of Oyster Bay Road and Highway 264. The Highway Patrol arrested 34 of the protesters, jailed 11 girls and two boys, and released 20 under the age of 16 as juveniles. The Hyde County Jail had been filled and the sheriff now scattered the arrested demonstrators among small-town prisons 60 to 90 miles away.

More than 100 marchers, including many parents and toddlers, held a prayer service at the courthouse the next day. Marching back toward Job’s Chapel, 15 to 20 teenagers left the procession and began skipping rope on the highway. When state troopers arrested them, they dashed rambunctiously toward the jail until a squad of troopers interceded and corralled them into an orderly line.

The protests had already filled so many of the closer jails that Sheriff Cahoon transferred a dozen girls to the Greene County jail in Snow Hill, more than 100 miles west of Swan Quarter. Business leaders in some closer towns had grown worried that the prisoners would inspire demonstrations by local blacks, and at least two sheriffs would no longer accept detainees from Hyde County.

The protests continued incessantly, day after day. By the time district court convened on December 11, Judge Hallet Ward Jr. discovered the cases of 166 demonstrators on his docket. The next day, before an overcrowded courtroom, the judge found the first seven teenage boys on trial guilty, gave them suspended four-month prison sentences, and placed them on probation.

When court officers requested that the people in attendance stand for his exit, black citizens neither rose from their seats nor said a word. The judge repeated the order, but the crowd was again silent and immobile, and Ward ordered Sheriff Cahoon to remove the protesters. Though outraged, Ward did not hold them in contempt in order to avoid heightening tensions during the remainder of the court session.

Judge Ward was not so patient when district court reconvened in Swan Quarter on December 18. Confrontations, including another attempt to block the buses at the O. A. Peay School, had occurred daily during the court recess. When Ward found 29 more activists guilty that morning, 75 young people returned to the courtroom during the lunch adjournment and demonstrated against the verdicts by stomping their feet and singing movement songs. They were still at it when the judge reentered the courtroom at two o’clock, and they neither halted nor stood when Sheriff Cahoon called the court back into session. Ward found everybody not standing — 99 people in all — in contempt of court and had them carried to jail by state troopers.

March on Raleigh

As winter descended on Hyde County, heightening its isolation, the struggle began to broaden. More than a dozen SCLC activists visited Hyde County, including veteran James Bevel, a leader of the Selma march and the Nashville Movement.

On the afternoon of January 16, SCLC leaders welcomed home the last 67 demonstrators jailed under the contempt-of-court order. They then joined a mass meeting at a local church where black citizens debated and prayed over the school crisis until midnight.

The next morning, SCLC leaders announced that the Hyde County school boycott was no longer a local issue but a civil rights struggle of state and national significance. School boycotters halted the local demonstrations that had been held almost daily for five months, while Golden Frinks announced a march to the state capitol in Raleigh the next month. Boycotters hoped the march would galvanize public support, inspire other civil rights protests, and foster new momentum for negotiations.

Preparing for the marches required an enormous effort. Under the leadership of Milton Fitch, who coordinated the marches for the SCLC, Hyde County activists had to arrange transportation, find places to stay, and prepare food for an entire week. They had to meet with local civil rights groups along the march route, and for their own protection they had to discuss their plans thoroughly with state and local law enforcement agents.

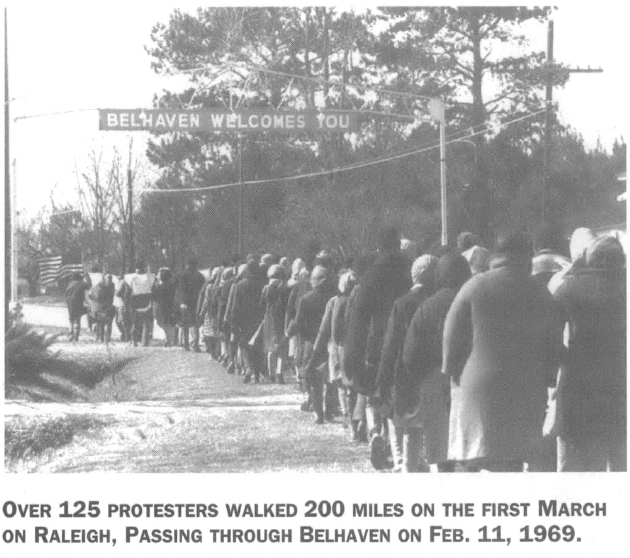

The first march, called simply the March on Raleigh, began at Job’s Chapel on the dismal, rainy morning of February 9. More than 125 demonstrators walked west on Highway 264 followed by a caravan of 55 automobiles, U-Haul trailers, and buses carrying food, bedding, and chaperones, Over the next six days, marchers traced a 200-mile route to the state capital, parading through towns and, between them, boarding cars and buses.

The marchers spent the first two nights at black churches in Belhaven and Washington, two coastal towns not far from Hyde County. They traveled the next three days through the heart of the Tobacco Belt and spent the evenings in Greenville, Farmville, and Wilson, the largest tobacco markets in the world. Along this route, local black residents displayed signs of solidarity. Many walked in the procession through their town, and civil rights groups held support rallies in Belhaven and Greenville. In Wilson, several hundred black students boycotted high school for a day to join the march, then accompanied them part of the way to Raleigh.

Bolstered by busloads of demonstrators from home on the final day, 600 marchers arrived in Raleigh on Friday afternoon, February 14. A crowd of supporters led by several hundred black students from Shaw University and St. Augustine’s College welcomed them to the capital.

State political leaders and other curious citizens crowded downtown Raleigh to watch the procession. Every available police officer was on duty. Three dozen state troopers stood nearby in case they were needed. Riot police wearing bullet-proof vests and antiterrorism gear waited at the Municipal Building, and National Guardsmen were on standby alert at the State Fairgrounds. Large numbers of plain-clothed SBI and FBI agents wandered the crowds and closely monitored the march.

The marchers proceeded slowly into the heart of the government district and held a long rally in front of the State House, with a keynote speech by the Reverend Andrew Young, who was then SCLC’s executive vice-president. Afterward, Young and boycott leaders met with the governor to express their concerns.

Mountain Top to Valley

When they returned from the first march to Raleigh, boycott leaders began to organize a second almost immediately, timing it to commemorate the first anniversary of the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. The Mountain Top to Valley March would approach the state capital from the opposite direction than the March on Raleigh. School boycotters planned to travel, again mostly by bus, 250 miles in 11 days, from Asheville in the Blue Ridge Mountains east to Raleigh.

But the march was marked by tragedy before its first step. On March 24, a carload of youths — one of several “advance teams” that had spread out along the route to organize local support — swerved into a pickup truck on a highway in Wilson, 100 miles west of Swan Quarter. Lucy Howard and Clara Beckworth, teenage girls from the Slocumb community, were killed on impact. The three other passengers were injured but not gravely.

Hyde County blacks were profoundly shaken by the wreck. Years later many people remembered the accident and the subsequent weeks of mourning more vividly than any other moment during the boycott. Most grew more determined to see the school boycott through, in Fitch’s words, “not wanting to let Clara and Lucy down” by failing to honor their example.

The Mountain Top to Valley March proceeded on April 4, following a meandering course from Asheville to Raleigh. The 75 marchers frequently changed their itinerary to respond to local events. In Madison County and Statesville, they helped black activists to consolidate school desegregation campaigns. They walked picket lines with textile workers striking at Cannon Mills in Kannapolis. White civic leaders greeted them as civil rights heroes in Valdese, and the Black Panthers welcomed them into Greensboro with open arms.

The most memorable episode of the march occurred in Concord, where the Ku Klux Klan waited in ambush for the Hyde County demonstrators. As the marchers neared the Klan, a sympathetic local white minister frantically spread word of the impending clash to black students at a high school and at Barber-Scotia, a black Presbyterian college. Hundreds of the students quickly left their campuses to join the Mountain Top to Valley March, and the Klan shrank back before their overwhelming numbers.

The marchers arrived somewhat disheveled in Raleigh on April 18, three days later than planned. Racial tensions were even higher in the capital than when the school boycotters had last visited, and they inflamed an already tense community. The Hyde County youths initiated their own nonviolent demonstrations and joined a peaceful march of several hundred from the Walnut Terrace housing project into downtown Raleigh. However, their stay also coincided with a series of fire bombings at the bus station, two state liquor stores, and several other public places. The Hyde County protesters could scarcely attract attention to the school boycott in so besieged a city.

Though most boycotters returned home after a few days of protests in Raleigh, several dozen remained in town for more than two weeks. Desperate to keep the school boycott in the public eye, the Hyde County activists attempted protests that were too ambitious to succeed so far from their local support. Golden Frinks of the SCLC conducted protests at the state capitol, obstructed access to the General Assembly, and tried to establish a “tent city” near the downtown area. When police arrested two boys under the age of 16 for interfering with traffic, he was charged with contributing to the delinquency of minors. District Court Judge Ed Preston Jr. gave Frinks a stiff one-year sentence on May 7, signaling the end of the campaign to occupy Raleigh.

Voting and Victory

The school boycott was still strong when the school year ended in early June. Black students had missed an entire year of classes, and some older children who might have graduated had instead left the county or found jobs, but black leaders declared that the sacrifice had been worth it.

In the end, they prevailed. Worn down by the sustained black protests, three school board members and Superintendent Bucklew stepped down. Their successors gave blacks a stronger voice in desegregation planning and expressed a willingness to keep black schools open.

That fall, white leaders essentially put the issue before the voters, asking them to decide a bond issue that would raise $500,000 to pay for enlarging the Mattamuskeet school. Faced with the threat of more black protests and higher taxes, even white voters rejected the original plan to expand the white school and opted instead to convert Peay and Davis into elementary schools.

The final settlement hammered out by biracial committees representing students, parents, and teachers did more than save the black schools. It retained black principals and teachers, incorporated black students fully into all extracurricular activities, preserved black cultural events, instituted an African-American history class, and established permanent committees to ensure parents a voice in their children’s education. Last, though hardly least important, the O.A. Peay school retained the name of its founder, who symbolized the educational aspirations and achievements of the black community.

For black citizens, sustaining the school boycott for an entire year had been a remarkable act of endurance requiring them to overcome poor weather, jail, the deaths of Clara Beckworth and Lucy Howard, and their own fears for the children’s educations. Yet they carried their struggle twice to the state capitol, and their school boycott fueled a broader movement for civil rights in Hyde County.

Today, two and three decades removed from those battles, a reassessment of school desegregation is beginning to occur. A few prominent black scholars have begun to emphasize what their communities lost during school desegregation, and others have started to rediscover the good qualities of African-American schooling in their search for new and better ways to teach children today. And in many Southern school districts that have drifted back to de facto segregation, black parents and educators are fighting against any school mergers, redrawing of districts, or busing that would dilute black community control by reintegrating the local schools.

In these ways, the complex issues that colored school desegregation a generation ago — issues of political power and cultural survival, ethnic traditions and community control — are again entering public discussion. The school boycott in Hyde County offers valuable insights into these challenges encountered in the attempt to create better schools and communities for all children.

Tags

David Cecelski

David Cecelski is a historian at the Southern Oral History Program, UNC-Chapel Hill. He is author of Along Freedom Road, which recently won a 1996 Outstanding Book Award from the Gustavis Myers Center for the Study of Human Rights in North America. (1996)