White Gold

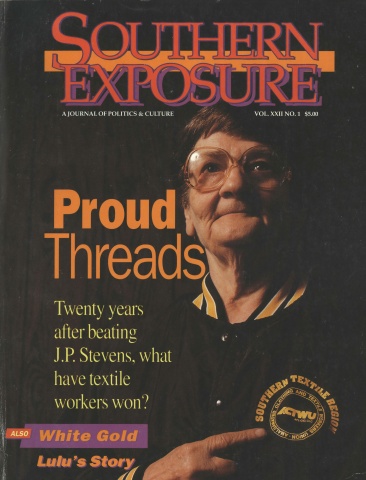

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

Deepstep, Ga. — Old Highway 85, the paved county road out of town, ends abruptly. Where the road used to be there is now a yawning pit more than 70 feet deep. Motorists must detour nearly half a mile on a badly rutted dirt road that leaves cars caked with mud when it rains.

In Washington County, where dirt roads are still common, local officials say their highest priority is to pave roads. But the county allowed ECC International to carve out a quarter-mile section of Old Highway 85 to mine kaolin, a crumbly white clay vital for making hundreds of products, from paper to china to toothpaste.

The company says its mineral lease gives it a right to mine the kaolin beneath the highway, even though the county owns the right-of-way. “We allowed the county to pave the road,” said ECC executive Carl Forrester, “and we will put it back the way it was after we finish mining.”

He gets no arguments from the county. Forrester, in fact, also speaks for the county. He is a county commissioner. Another of the five commissioners also works for the kaolin industry, and a third is retired from a mining firm.

In Washington and a half-dozen other counties in middle Georgia, kaolin is king — more than cotton ever was. Each working day, international mining concerns like ECC gouge thousands of tons of kaolin from the red, hilly soil of the region. Local folk call it chalk. The companies that mined more than $1 billion worth of kaolin last year call it “white gold.”

Nowhere else in the world is the quest for the lucrative white clay more energetic. Seven Georgia counties — among the poorest in the state — harbor an estimated 60 percent of the world’s purest kaolin reserves.

But the people of the kaolin counties see only a trickle of the mineral wealth dug from their soil. Family homes, barns, and corncribs have been moved or torn down to make way for mining operations. In return, landowners often get less than the cost of fill dirt — as little as a nickel a ton — for their kaolin. Many kaolin companies pay each other up to 100 times as much for the same raw clay.

Landowners who protest are reminded that the mineral leases they or their parents signed allow mining companies to remove any “improvements” that stand in the way of clay. When the kaolin is gone, what remains are swaths of eroded land, unsuitable for crops or timber for decades to come.

Taxpayers get even less than landowners. If Georgia taxed its minerals at rates similar to other Southern states, kaolin would generate an estimated $65 million annually. In all, 35 states tax their mineral wealth. But Georgia asks for — and gets — nothing.

“I’m opposed to a severance tax of any kind,” Governor Zell Miller said. “I believe it is anti-business and anti-jobs.”

The official pro-industry stance has cost kaolin-rich communities a fortune. “These counties should be some of the wealthiest in Georgia because of the mineral wealth in the ground,” said Guy Thompson, tax appraiser for Wilkinson County. “Yet we are some of the poorest: We have second-rate law enforcement, second-rate health care, and second-rate schools.”

Spokesmen for kaolin companies say the industry operates on a very thin profit margin and cannot afford more taxes. But they will not say what that profit margin is, or how much is earned from the clay mined in Georgia, or what they pay to individuals for mining leases.

They do say the business is so competitive they must keep costs as low as possible. But the six major kaolin companies control so much of the world’s kaolin production — through the next century, and perhaps for many centuries to come — that Justice Department officials visited Georgia in January to investigate the industry for alleged criminal anti-trust violations.

“When I was in the legislature, everybody seemed afraid of the kaolin industry except for only a few of us,” said Georgia Revenue Commissioner Marcus Collins, who tried and failed to enact a mineral tax while in the state House. “The whole state of Georgia is being denied a rightful share of the wealth.”

Dogs and Billy Clubs

Kaolin was first deposited in middle Georgia roughly 70 million years ago, when the region marked the meeting place of land and ocean. Erosion washed the clay from the Appalachians down to what was then the coast of the Atlantic.

Today kaolin accounts for two-thirds of all the minerals produced in Georgia each year. It is an essential ingredient in paint, plastic, rubber, kitchen and floor tiles, and ceramics. It is a key component in many plaque-fighting toothpastes, cosmetic face creams, and over-the-counter stomach cures. It is also used to coat glossy paper; a copy of Newsweek is about 30 percent kaolin by weight.

Yet few people, even in kaolin country, know what the clay is really worth. Anyone who wants to know the price of silver, oil, uranium, or gold need look no further than a newspaper’s daily commodities listings. Most valuable minerals are traded on an open market, but kaolin companies refuse to make public the prices at which the clay is bought and sold.

In spite of the secrecy, an examination of court depositions and internal industry documents reveals the companies pay each other up to $5 a ton for unmined kaolin. The highest-grade refined kaolin for paper sells for up to $460 a ton. The purest grades for medicinal purposes sell for up to $717 a ton.

Most of the firms doing the buying and selling in Georgia are foreign. Four of the six largest kaolin companies are owned or controlled in part by corporations based in England, France, Finland, and South Africa. Two are connected to Anglo American Corp. of South Africa, the world’s biggest mining conglomerate.

“It’s a ruthless industry,” said Wendell Dawson, now assistant state attorney general for Tennessee, whose family is from Washington County. He said sheriff’s deputies unleashed dogs on his grandmother in 1950 and beat her with billy clubs to drive her from her home, which stood in the way of kaolin miners.

“She took her hurt with her to the grave,” Dawson said. “My family still feels the pain.”

Local residents, attorneys, and some public officials say the kaolin industry in Georgia is founded on forged deeds and questionable business dealings. Companies exploit the ignorance of local residents, they say, while cloaking their actions in commercial secrecy.

“The chalk companies beat just about everybody out of the clay,” said Hilliard Veal, a retired Deepstep store owner who inherited valuable kaolin deposits from his father. “It didn’t make any difference whether you were black or white. Most people were ignorant over the value of kaolin, and the companies kept everything so secret that the landowners could never find out what their clay was really worth.”

Old Deeds and Shady Deals

The power of the industry springs from lease contracts it began securing in the 1930s, when people first realized that fortunes could be made in Georgia’s white clay. Mining companies and entrepreneurs started signing up the people who owned the “chalk land” to long-term mining leases. They gained control of thousands of acres of kaolin land and millions of tons of mineral reserves, often without ever telling the owners what was on their land.

The contracts usually gave companies the right to mine the land for up to 99 years and pay the owner as little as a nickel a “crude ton” — 2,733 pounds. The now-defunct Department of Mines even handed out brochures advising landowners to sign the leases.

“Once the lease was signed,” former kaolin executive Haydn Murray acknowledged in a 1990 sworn deposition, “the landowner effectively relinquished absolute control over his will to the conduct of mining and the development of his mineral interests.”

Though now faded and yellow, hundreds of contracts are still valid — still shaping the economy of the entire region and exerting tremendous leverage over people’s lives, livelihoods, and the laws they live by.

Many were led to believe that mining would start almost immediately. Yet 20 to 40 years after signing the contracts, many have yet to see the first ton of dirt dug from their land.

Although courts in other states — including Florida and Texas — have declared similar contracts null and void if a company waits too long to start mining, the Georgia Supreme Court in 1983 declared the kaolin leases valid.

Land agents, most of whom represented Northern-based mining companies, say in court documents that the rush to get a signed contract was so frenzied that often they would not even take time to make sure the people they were signing up actually owned the land. Many landowners say forgery was so rampant that signatures on scores of old deeds and mining leases — still in effect — are believed to be illegal.

Several families are suing in U.S. District Court in Macon. In chalk country, however, justice takes time. While the average civil case takes 20 months in Macon, some lawsuits against kaolin companies have been pending for more than seven years. The court records are routinely sealed.

Today, scores of mining leases signed decades ago are coming up for renewal. Kaolin firms say they are offering landowners better deals, including more liberal royalty rates.

“Our relationship to the landowners is very important to us,” said Rob Morton, chairman of the China Clay Producers Association, the trade group that represents Georgia’s leading kaolin producers. “When we make a deal with them, we want to be fair, because we want to be well thought of by our neighbors.”

But an examination of several new leases negotiated in recent years shows that landowners are not getting much better deals than their parents or grandparents got. While the new royalty rates may be two to seven times higher than the old leases, the prices of refined kaolin have increased by a factor of 10 to 16.

When negotiating new contracts, the companies often change the unit of measurement on which the royalty is based. An old lease, for example, may have given the landowner 25 cents per “refined ton” of kaolin, or 2,200 pounds. The new lease may pay 50 cents per “cubic yard,” which weighs only about 1.7 tons — giving the landowner only a few pennies more than the old lease.

“You might think you’re getting a good deal, only to find that a ton ain’t a ton,” said Hilliard Veal, the retired storeowner.

Babies and Bibles

If there were hundreds of landowners willing to sign the lease contracts, there were also hundreds of others reluctant to do so. Many owners were suspicious of the “chalk people” and refused to let them explore their land for kaolin; others said they didn’t want to relinquish control of homes that had been in the families for generations.

The kaolin companies, however, had other ways of getting at the chalk.

“Some men with a drilling rig would show up at a farm and offer to drill a well for free,” said Frank Fountain of Wilkinson County, who once owned a kaolin company. “The farmer got a well, but the drillers got core samples, which they tested for kaolin without ever telling the farmer.”

If they found that a piece of land harbored desirable deposits and the owner was reluctant to sign, the company waited until the owners died and approached heirs who might be more receptive.

Burl and Ellen Gibson, subsistence farmers who owned 130 acres in Wilkinson County, were among those who wouldn’t sign. Mrs. Gibson inherited the farm in 1941 when her husband died. When she died in 1945, she left it to her son, Griffin Gibson, a daughter, and an adopted nephew.

Just six months after her death, a now-defunct kaolin company called Southern Clays persuaded Griffin Gibson and his sister to sign a 20-cents-a-ton lease. When the company drilled the land in the early 1960s, it discovered nearly two million tons of high-grade kaolin worth at least $1.4 million.

Company officials urged Gibson to sell them the land. According to family members, a company “strawman” named John Scott courted the unsuspecting landowner, stopping by his house nearly every day. The two men squatted under a tree or sat on a porch and chatted about the weather or the cotton crop.

“Not One Red Cent”

In 1980, a group of tax experts appointed by the governor and state legislature concluded that Georgia’s largest mining companies were not paying their fair share of property taxes. They suggested state and local governments were losing a fortune.

Fourteen years later, not much has changed. Georgia still exports its mineral wealth largely tax-free. Middle Georgia counties where kaolin is mined still rank among the poorest in the state. And tax officials say the mining companies still are not paying their fair share.

“The average mine site is about as significant as a house across the road in terms of the taxes you’re going to get off it,” said Guy Thompson, tax assessor for Wilkinson County. “I’m not trying to say it’s fair — that’s just the way it is. ”

The tax inequities in kaolin counties are remarkable:

▼ In Wilkinson County, kaolin property that sold for more than $5,000 an acre went on the tax books for $250 an acre. Property owners in the county pay roughly $700 in taxes on an $80,000 home — while kaolin companies pay less than half that amount for mines in which they have invested millions of dollars.

▼ In McDuffie County, mineral owners report their reserves at pennies an acre for tax purposes. “That won’t pay to send out the tax bill,” said Chief Appraiser Wayne Smith, “so we put a minimum 50 cents per acre on them so the county wouldn’t go in the hole sending out the bill.”

▼ In Twiggs County, Dry Branch Kaolin Company paid $3.21 an acre in taxes on 6,372 acres that yield clay worth millions of dollars — the same tax rate as farmland without kaolin.

The tax consequences of undervalued kaolin property are tremendous. “If the counties assessed mines properly, it might cut the mill rate in half,” said Ronald Rowland, an independent tax appraiser with considerable experience in valuing kaolin properties. “The poor individual is the one who is paying.”

Schools and local governments bear the brunt of the unfair tax decisions in kaolin counties, but taxpayers across the state pay part of the tab. Because of their anemic tax base, several kaolin counties require support from richer parts of the state to maintain essential services.

More than $250 million worth of kaolin was mined in Twiggs County in 1991. That same year, the county needed an additional $3.3 million in tax revenues from the state to pay for its schools, roads, and social programs.

“Most of the tax burden is falling on individual property owners’ backs, and we’re tired of it,” said Ray Tompkins, head of a 650-member homeowners’ association in Wilkinson County trying to get kaolin companies to assume more of the tax load. “We often have to borrow money to keep the schools open.”

The kaolin industry warns that trifling with the status quo threatens to make Georgia clay less competitive. “They could bring in people to assess and tax kaolin,” says James Groome, executive director of the China Clay Producers Association, “but it would be killing the goose that laid the golden egg.”

In the 1980s, the coal industry in Kentucky made a similar argument after a ragtag group of citizens began calling for coal reserves to be taxed. The companies won in the state legislature, but the courts ruled that the state constitution requires equity in property taxation — all taxpayers are supposed to be treated alike and all property is subject to taxes. Coal companies now pay property taxes on more than $1 billion in coal reserves.

Georgia’s constitution also requires tax equity, and state law says property taxes should reflect mineral values. But local tax officials are reluctant to take on big mining companies, and State Revenue Commissioner Marcus Collins admits his staff is also outgunned by the powerful multinational corporations.

“The kaolin companies are taking all these minerals from one of the poorest sections of Georgia, but they’re not paying the counties or the state one red cent for them,” he said. “The state and the counties are entitled to some money for their minerals.”

The tax debate has started to heat up in recent months. This winter, the state legislature began considering a bill that would tax kaolin after it is mined. Industry officials have been mustering forces to shoot down the severance tax, but proponents say it could bring in as much as $65 million a year — roughly 25 percent of what the lottery is expected to generate annually.

After years of supporting the industry, it now appears that some local leaders are ready to take on the kaolin companies. At a meeting of the Wilkinson County Commission last fall, Chairman J.M. Howell asked industry representatives who would be pushing the severance tax in the legislature.

Why did Howell want to know the names of tax supporters? “So they could come talk to us,” he said.

— Charles Seabrook and Richard Whitt

Gibson came to consider Scott one of his most trusted friends. When a baby was born in the family, Scott gave $10 as a gift to the infant and asked if he could look up some of the family’s names in the family Bible.

The family now suspects that Scott really wanted to examine the family tree written on the flyleaf to see how many heirs he would have to contact in order to secure rights to the kaolin.

In 1962, the company bought the Gibson farm for $40,000. After the closing, Scott never visited the house again. Exactly a year later, Southern Clays sold the land to another clay company for $1.4 million.

Festivals and Footraces

White clay leaves little untouched in chalk country. People can fly into Kaolin Field airport, shop at the Kaolin Plaza, and buy flowers at Kaolin Florist in Sandersville, where sprawling kaolin processing plants punctuate the skyline.

Every October, townsfolk crown a Miss Kaolin during their annual kaolin festival. There is an annual 10-kilometer footrace called the Kaolin Canter.

Road signs are often covered with white, powdery chalk. The narrow highways are tinged with a snowy whiteness, and meandering streams run milky white with clay silt when it rains.

Twice a day from Deepstep — “the Kaolin Capital of the World” — a train pulling more than 100 cars brimming with kaolin pulls out on the 10-milelong Sandersville Railroad. So lucrative is the kaolin traffic that the short trunk line is known as one of the world’s richest railroads.

The shorter line hooks up with the Norfolk & Southern railroad in nearby Tennille, where “kaolin expresses” haul clay to Atlanta and Savannah. So many freighters laden with kaolin steam from the Port of Savannah every year that the mineral is the single biggest product shipped by the state Ports Authority.

To slake the insatiable industrial thirst for water to process and ship the mineral, local kaolin plants consume 59 million gallons of private well water a day — more than the cities of Augusta or Macon use. It’s not uncommon for wells in the area to go dry, homeowners say, or for the water they produce to be white with kaolin silt.

Industry officials say mining has brought a degree of prosperity to what is otherwise one of the most economically depressed regions in the state. Kaolin companies currently employ 4,500 people to mine and process the valuable mineral.

But “chalk mines” bring more than jobs to middle Georgia. Kaolin counties are a mosaic of eroding craters, acres of rusty-red and tannish-white clay pits surrounded by gullies big enough to drive a Jeep through. Although many of the former mines have produced no kaolin in years, the state Department of Natural Resources (DNR) continues to list them as “inactive” — allowing kaolin companies to delay reclaiming mined-out land almost indefinitely while the soil continues to wash away.

Georgia has one of the oldest and weakest surface-mining laws in the nation. Unlike federal rules applying to coal mines, the state requires no public notice before it issues a kaolin mining permit, and places no time limit on permits. A check of the permits on file shows that DNR also routinely waives bonds for kaolin companies — the state’s only insurance that a kaolin mine will be reclaimed should a company not do so.

The state has never revoked a bond or rescinded a permit against a kaolin company. It would be hard for state officials to even check compliance. Because of recent budget cuts, DNR has assigned only one field worker to inspect most of the southern half of the state, including the kaolin mines in middle Georgia.

Industry leaders say their companies have spent more than $2.6 million a year to reclaim about 29,000 acres of mined-over lands since 1980. ECC International, the biggest kaolin producer in the state, created an award-winning park with fishing ponds on reclaimed land in Deepstep.

Rich Clay, Poor Counties

Seven Georgia counties that yield $1 billion in kaolin each year suffer higher poverty and lower education than the rest of the state.

Median % %

Household Living in High School

County Income Poverty Graduates

Glascock $21,806 16.8 50.3

Jefferson 17,076 31.3 49.7

McDuffie 21,292 21.6 56.1

Twiggs 19,213 26.0 48.4

Warren 17,284 32.6 42.8

Washington 21,460 21.6 58.1

Wilkinson 25,166 15.3 62.0

Georgia $36,945 14.5 71.1

But no one is under any legal obligation to reclaim the thousands of acres mined before the state’s land-reclamation law went into effect in 1969. In middle Georgia, there is up to 40,000 acres of so-called “orphan land.” As a consequence, broad swaths of land repeatedly sliced by gullies and rippled like a giant washboard can be seen throughout kaolin country.

It is sometimes difficult to tell land that has been reclaimed from abandoned orphan land. Large tracts of reclaimed land also show serious erosion. Even after a decade of growth, pine trees on some tracts are stunted, averaging no taller than a living-room Christmas tree.

“We are proud of our reclamation efforts,” said Lee Lemke of the Georgia Mining Association. He shows visitors appealing pictures of mined land restored to rolling, grassy fields and farm ponds.

Residents see it differently. “We sure got the farm ponds, that’s for sure,” said Hilliard Veal, the retired Deepstep store owner. “That’s about the only thing you can do with these deep pits.”

Tags

Charles Seabrook

Charles Seabrook is a reporter with the Atlanta Journal and Constitution. His reporting on kaolin won second place in the annual Southern Journalism Awards sponsored by the Institute for Southern Studies. (1994)