This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

An hour before dawn on a dewy May morning, Cindy Chattin left her home on the edge of the old mill village and drove the few blocks to the Cone Mills textile plant in Salisbury, North Carolina. But instead of reporting to her post at the colormatic machine on that chilly day, she met 100 of her co-workers outside the plant gate. For the next 12 hours they marched, carrying placards with messages like “Cut us in, Cone.” And they sang:

We are the union,

The mighty, mighty union . . .

“People were just ecstatic,” says Chattin, a 15-year Cone veteran. “We were just down there marching and singing, and our plant manager was going crazy. He was going crazy. He had the police out there, and he tried to have people arrested.”

The cops did issue six citations for picketing without a permit. And throughout the day, the plant continued churning out denim and flannel. But neither police nor production could dampen the mood outside.

“Morale just shot through the roof,” Chattin says. “People were really hyped up.” Perhaps most exhilarating were the reactions of some non-union workers: They got out of their cars, talked to their co-workers, and then refused to cross the picket line.

Although the one-day strike in 1992 resembled a typical union demonstration, the walkout involved none of the ordinary bread-and-butter issues of organized labor — wages, health benefits, safety, or job security. Instead, it focused on the Wall Street wheeling and dealing that typified the 1980s — and its impact on blue-collar textile workers like Chattin.

Ten years ago, to fend off a hostile takeover by a New York company, Cone Mills created an Employee Stock Ownership Plan (ESOP) as part of a $465 million buyout scheme. Cone promised the plan would make workers part-owners of the world’s largest denim manufacturer — and tie their fortunes directly to their own hard work.

Instead, union members now claim, the ESOP cheated the very employees it was supposed to empower. At the same time, top Cone executives earned millions from the deal.

Outrage over the ESOP sparked a shop-floor revolt among the millworkers. “They were furious about it, and it wasn’t a fury that the union put into place,” says Michael Zucker, director of corporate and financial affairs for the Amalgamated Clothing & Textile Workers Union (ACTWU). “It was an anger we recognized.”

Even though the Cone Mills struggle revolved around a newfangled issue, it served as a reminder that the tried-and-true methods of union organizing work. The workers emerged victorious, and the ESOP campaign helped resuscitate the union at Cone Mills factories in Salisbury, Greensboro, and Haw River. Before the strike, union membership at the plants had fallen below one-third of the hourly workforce. By last year, membership had doubled.

“While this particular issue and the feeling the workers had were particular to the situation at Cone Mills,” says Zucker, “the notion that workers can be mobilized to a historic extent on the right issue is true in every instance.” But it takes good research, good planning, and a union that’s willing to listen to its members.

Christmas Hams

The White Oak denim plant dominates the sprawling Cone Mills complex north of downtown Greensboro. Three smokestacks tower over the jagged roof, their steam casting shadows on the factory’s brick walls. A two-mile-long chain-link fence, topped with six strands of barbed wire, surrounds the mill. Gulls circle the parking lot. From the sidewalk, smokestacks from other Cone plants nearly blot out the downtown skyline.

The mills have loomed over the cityscape — and over the lives of their workers — for the past century. When Moses and Ceasar Cone, German Jews who ran a New York export business, moved to Greensboro in 1893, they created a mill village with three textile plants and enough housing for 15,000 people. It was decent shelter — far better than the “packing boxes on stilts” that workers elsewhere endured.

“Often the Cones ambled through their industrial hamlets, greeting workers and family members by their first names, exchanging pleasantries, and chatting with them on their front porches,” writes labor historian Bryant Simon. “They appeared at church meetings, presented children with Christmas gifts, offered advice on gardening, and addressed the annual father-son banquet.”

The cozy relationship was part of an industry-wide strategy known as paternalism: a system of convincing millworkers to identify wholly with the company. The Cones even held an Independence Day picnic with string bands, three-legged races, and enough fried chicken to feed 10,000. They bought shoes for needy children, gave away Christmas hams, and sponsored cooking seminars, hygiene classes, and beet-growing contests.

But they didn’t tolerate labor organizers. In 1900, when 150 Cone workers secretly joined the National Union of Textile Workers, Cone slammed the mill gate and locked the company store. Finally, according to Simon, they broke the union by evicting scores of families from their homes.

But it wasn’t until the “stretch-out” of 1925, when the Cones laid off hundreds of workers and sped up production, that employees saw the real limits of their bosses’ benevolence. Even before the union arrived, 2,000 mill hands and their relatives gathered at the plant gate to sing hymns of discontent. “We work for a song, an’ do all the singing,” declared one striker. In May 1930, despite company pressure, 1,500 workers gathered at an empty potato patch for their first union rally.

The union did not take firm hold until after World War II, when Cone sold off the mill houses and cut benefits, breaking the paternalistic bond. Throughout the post-war years, union membership rose and fell, often in response to specific initiatives by the company or the union. North Carolina’s “right to work” law, which allows workers to enjoy the benefits of a union contract without paying dues, made recruiting and holding on to members even more difficult.

During the 1960s and ’70s, a group of young firebrands got involved in the union, and members experimented with new tactics to secure their position in the mills and gain a stronger voice when contract re-negotiations rolled around. “People began to stand up,” says Marie Darr, a former Cone worker and now an ACTWU organizer. “A lot of black workers got involved — feeling like the union was a fighting organization.”

ACTWU made some gains in the early ’80s, winning automatic payroll deductions for dues and improving wages and benefits. But even long-time members say the union was unprepared for what happened in 1983.

That was when the crisis hit.

The New Paternalism

The crisis was an attempted takeover of Cone Mills by Western Pacific Industries, a little-known New York holding company. Western Pacific, formed in 1970 to buy a railroad, had quietly accumulated some $16.5 million worth of Cone Mills stock. In November 1983 it announced its plans to purchase $30 million more from Ceasar Cone II, the founder’s son, and take control of the firm.

Both management and workers agreed the takeover needed to be stopped. “This is like the old home place,” James Watts, a fixer in yarn preparation, told a reporter. “If you tear it down and put something else up here, it’s not going to be the same. We are family in there.”

The company scrambled for solutions — and decided to plunge $465 million into debt. Cone borrowed $420 million from 10 banks and issued $45 million in new stock to its top executives. With this cash, the management completed a “leveraged buyout,” taking the company off the stock market and making it private. Western Pacific dropped its takeover bid, selling its stock for a $23 million profit.

Dewey Trogdon, chair of Cone Mills, called the buyout a gamble. If it succeeded, he predicted, “I’ll have some rich grandchildren.”

The firm also found another source of money. “Cone’s pension plan was overfunded,” says Carolyn Hines, employee-communications manager for the company. The fund contained $69 million more than Cone needed to pay retirement benefits, so Cone skimmed off the cushion to pay some of its massive debt. In exchange, it promised to put an equivalent amount of stock into an Employee Stock Ownership Plan, which would fund future retirement benefits.

ESOP-linked leveraged buyouts were a creation of the Reagan era, with its promotion of high-stakes financial deals. The schemes allowed company executives to divert pension funds to other uses — often to stave off hostile takeovers. According to Fortune, the tax advantages were “dazzling.” The magazine also noted that many ESOP plans “left employees . . . holding nothing but the bag.”

Trogdon promised that wouldn’t happen at Cone Mills. In fact, he assured workers the ESOP would elevate their status. “Since the [ESOP] will become an important source of your future financial security, you will have a personal stake in the Company’s future,” he wrote in 1983. “As a Company stockholder, your performance will directly influence the value of the stock in your personal ESOP account — forming a real bond between your efforts, the Company’s success and your financial security.”

This new kind of paternalism, which encouraged employees to invest themselves fully in the company, appealed to workers. Many feared Western Pacific would shut down factories as soon as it bought Cone Mills.

“I was concerned about maintaining my place of occupation,” says James Graves, a part-time minister and a forklift operator at the Haw River plant. “At the time it sounded like a good idea.”

So Graves, like other union representatives, agreed to the plan. ACTWU checked for irregularities and illegal provisions. Finding none, it okayed the deal.

One reason workers deferred so readily was that Cone placed 25 percent of each worker’s annual wage — far more than needed to fund the pension — into the ESOP account during the first year. This extra money was called a “surplus,” and workers say the company told those who didn’t want to wait until retirement that they could withdraw their windfalls in 1990 — to buy houses, cope with medical emergencies, or send their children to college.

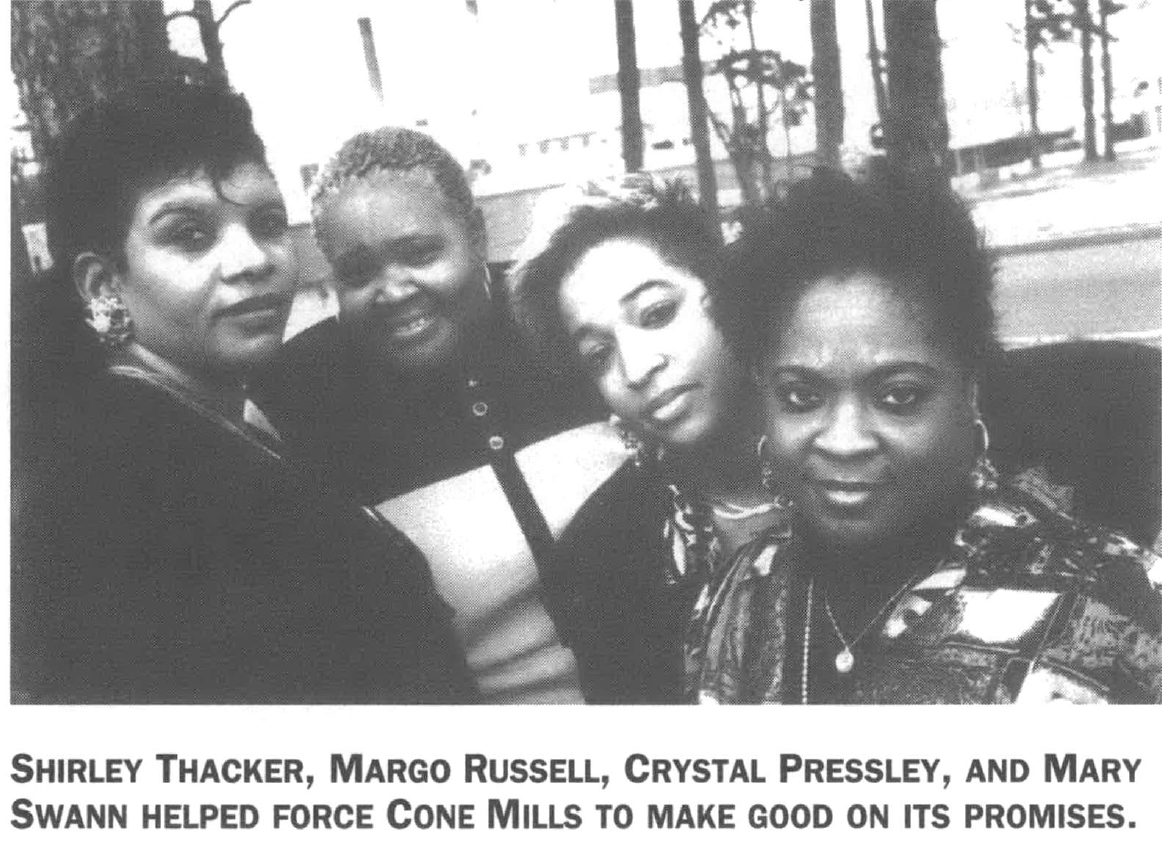

“They took us in the office, told us we were part owners, and in 1990 we would get the money,” recalls Margo Russell, an imposing, gray-haired woman who spins loose cotton into yarn at the White Oak mill.

Shrinking Surpluses

When 1990 rolled around, workers tried to get their money. Cone told them it wasn’t available, that there’d been no pledge of early withdrawals. “They were never told that,” insists Cone Mills spokesman Frank Fary. “In all of the descriptions and meetings with employees, the plan was described as a retirement plan.” He says Cone told workers some benefits wouldn’t be paid until 1990, to protect Cone’s cash flow. “That’s where people got confused,” he says.

Workers tried to discuss the pension money, but Cone refused to budge. “We went to wage negotiations and tried to bring up the subject,” says Cindy Chattin. “The company didn’t want to hear it.”

Being a “part-owner” in the company apparently didn’t give Chattin or her fellow workers much say. In many ways, things hadn’t changed. Decades earlier, Chattin recalled, in a nearby mill town called Cooleemee, her grandfather had joined the union — only to receive an immediate promotion to supervisor. When the union called a strike, her grandmother and other supervisors’ wives were ordered to scab while their friends walked the picket line.

Chattin chose to break with family tradition. She and other millworkers turned to the union.

ACTWU did some research and made some sobering discoveries. Cone had put only $54.8 million into the ESOP — $14.2 million less than it had taken from the pension fund. By depositing “surplus” money into each worker’s account, the company had also pocketed a $17 million tax break for itself. But workers and their families could not collect their money until they retired, quit, died, or became disabled. They had no control of their own finances.

Worse, their surpluses were shrinking. After the first two years, the company had cut its annual contribution to one percent of wages, which was not enough to fund retirement benefits. So the company began chipping away at the surpluses to keep the pensions funded. The longer workers stayed, the less windfall they could expect at retirement.

ACTWU called a series of meetings at local union halls to break the news to its members. At one meeting, Michael Zucker asked how many people had been told they would be able to get money from the ESOP in 1990. “Everybody’s hand went up,” Zucker recalls. “When we said, ‘No, you’re not,’ everyone went bananas.”

Like the “stretch out” of 1925, the about-face on the stock plan reminded workers that paternalism has its limits. “People were upset because they felt the company had actually betrayed them,” recalls Margo Russell, who has worked at Cone Mills for nearly 19 years. “A lot of the people in that plant, they felt like anything the company said, it was just like the truth to them.”

So the union launched a campaign to give workers access to their ESOP money. Jesse Jackson came to Greensboro to kick off the crusade. Workers picketed outside the banks that financed the leveraged buyout. The union filed a lawsuit, and more than 2,000 employees filed a complaint with the U.S. Labor Department. ACTWU held a short strike during contract negotiations.

In October 1990, the union chartered four buses and two vans to bring 267 workers to a non-union Cone plant in Cliffside, North Carolina. “We were out in the boonies — the serious boonies,” recalls Cindy Chattin. “They didn’t know anything. They didn’t hardly know what the ESOP was, and they certainly didn’t know what the surplus was.” The non-union workers also seemed wary, and gave union members “a very cold reception.”

But later that evening, the union members stopped for dinner on the local burger strip and fanned out to two fast-food restaurants. Cliffside workers, getting off their shifts, joined them and suddenly seemed more receptive. “People were coming in: ‘What is this ESOP? What is this surplus?’ People were telling us about the job loads they had. It was incredible the difference between their job loads and our job loads,” Chattin recalls.

Cone Mills fought back. “In visiting some of Cone’s nonunion plants this week, the union is attempting to make the ESOP an issue with you, by their continuing misrepresentations of the facts about the ESOP to benefit their own selfish purposes,” wrote plant manager Larry Barnes to his workers.

In another letter, Cone president J. Patrick Danahy reminded his employees, “If the union believes there is something wrong with the Company’s contribution to the ESOP, why did they agree to it in 1984?” Danahy charged the union’s statements “are intended only to sign up new members.”

Contempt of Court

Then, in 1992, Cone announced plans to go public again. The ESOP stock, valued at $100 a share, would remain at exactly $100. But stock held by 47 top executives would increase 12-fold in value, from $8.3 million to $107 million. Later it soared even higher; shares bought for $1 each now sell for more than $16, a 1,500 percent jump. “There were a lot of millionaires made,” says Zucker.

Frank Fary, the Cone Mills spokesman, says mill executives bought their stock with their own money and were “subject to great risk,” while ESOP stock was relatively stable and funded by the company. “We the management were unwilling to put employees’ retirement funds at risk,” he says. “The same decision would be made today.”

Anyway, Fary says, the ESOP stock paid respectable dividends to workers’ accounts. As of March 1992, a $100 share paid $114 in dividends — “competitive” with other investments, he says.

Fary maintains “the real issue in connection with the ESOP was, ‘Give me some money. I want it now.’ I guess that’s human nature.”

Marie Darr, the ACTWU organizer, sees it differently. While management profited, workers weren’t sharing in Cone’s success. “They felt like they had been cheated,” she says. “They felt like they had been misled. They felt like they had been betrayed.”

ACTWU stepped up its campaign. On the shop floor, workers wore badges and ribbons proclaiming their allegiance to the union. They held pre-dawn prayer meetings outside the plant gate. “We had the superintendent coming out of the building,” recalls yarn handler Mary Swann, a 25-year employee. “They thought we were getting ready to strike.”

Workers packed the canteen and sang “Solidarity Forever.” They circulated petitions throughout the plant. They filed repeated grievances. “We ran that place,” says Crystal Pressley, a White Oak worker. “We let them know — we’re not scared.”

As the rage grew, the tactics got more dramatic. More than 200 workers marched up the hill to Cone headquarters in Greensboro, carrying signs saying “Share the wealth!” and “A deal’s a deal!” Millworker Jimmy Seymore donned a judge’s robe and white wig, and pounded a gavel for order. After a mock trial, Seymore pronounced his verdict: “They’re in contempt of my court,” he shouted. “Cone Mills has no defense!” The crowd went wild.

Two weeks later, a group of Cone workers took their boldest step: They brought their complaints directly to Wall Street. About 50 hourly employees went to the offices of J.P. Morgan Securities and Prudential Securities, the lead underwriters of the 1992 stock offering. They met with bank officials and passed out leaflets to employees.

Cone officials dismiss the New York trip as a publicity stunt. But workers say they made an impact. “A lot of people passed us by and they said, ‘You keep fighting,’” says 18-year veteran Shirley Thacker, a spinner in the White Oak plant. As for the bank officials, “They told us, ‘You all go back to Greensboro and talk to Cone Mills — but we’ll call them.’”

Next day, the union members reported to work wearing New York T-shirts. “They was real quiet, the company management was,” laughs Thacker.

The Victory

A month after the New York trip, Cone Mills gave in and agreed to negotiate reform of the ESOP. In February 1993, ACTWU and Cone finally reached an agreement affecting 2,800 workers.

Under the settlement, Cone agreed to release $15.4 million in ESOP funds. Workers could withdraw the money, roll it into other retirement plans, or keep it in their ESOP accounts. The union claimed victory.

Cone says it’s comfortable with the outcome. “I think it was a very positive move on behalf of the company,” says Frank Fary. “There are people who took out $8,000, $10,000, $12,000. That’s kind of exciting. That’s a pretty good deal. I feel good about it.”

The agreement hardly represented a balancing of the scales. In a case still under appeal, a federal court ruled last fall that Cone didn’t break the law when it shortchanged the ESOP by $14.2 million. What’s more, the settlement didn’t rectify the fact that Cone executives earned millions off a deal that only marginally benefited workers.

Still, union members at Cone Mills consider the agreement a big victory. After the plan was signed, Greensboro workers filled the nearby union hall to celebrate. The union gospel choir, Voices in Harmony, sang “Victory is Mine.” The mood was electric.

“The struggles, the fights, Jesse Jackson, all that was good,” says Margo Russell, the spinner at the White Oak mill who also directs the union choir. “But to see people come out — even people who weren’t in the union — that was great. That was big.”

Tags

Barry Yeoman

Barry Yeoman is senior staff writer for The Independent in Durham, North Carolina. (1996)

Barry Yeoman is associate editor of The Independent newsweekly in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)