Sewing History

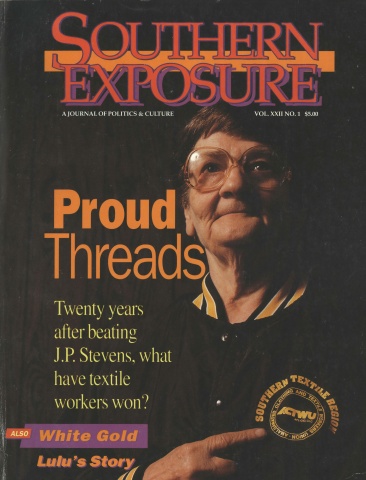

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

In the summer of 1990, I joined veteran filmmaker George Stoney to produce a documentary film about the General Textile Strike of 1934. George, a pioneer in community-based media, had been chosen to make the film by a research consortium of Southern scholars, union members, and community leaders assembled by labor economist and activist Vera Rony to study this watershed moment in Southern labor history.

The uprising involved hundreds of thousands of mill workers and challenged the traditional system of paternalistic control by textile bosses. But the popular memory of this pivotal organizing campaign had been lost — silenced by fear, distorted by the media, and omitted from school textbooks. The consortium wanted to reclaim a history of protest for a new generation of workers — a task that would prove far more difficult than any of us anticipated.

When I joined the project, I was handed a videotape that contained the Fox Movietone newsreel footage of the strike. Raw, unedited outtakes revealed initial hopeful protests, including an unauthorized Labor Day parade by 10,000 workers in Gastonia, North Carolina and a spirited speech from atop a car by a rank-and-file organizer named Albert Hinson. Most of the footage, however, focused on scenes of havoc and violence. Soldiers armed with a machine gun guarded the Cannon Plant in Concord, North Carolina. Union members from across the region held a mass funeral for six strikers shot in the back in Honea Path, South Carolina.

Edited newsreels shown in theaters across the United States during the fall of 1934 reinforced the images of terror. On the screen and in the streets, the guns and bayonets of the mill industry seemed indomitable. Images of solidarity and celebration — when shown at all — seemed suspect or sinister.

This footage posed a quandary faced by all filmmakers who document labor themes: How could we go beyond the stereotypical newsreel images of violence and death to tell the drama of grassroots organizing not captured by the movie cameras? We wanted to recount the day-to-day nurturing of a labor movement based on citizenship that had inspired communities of cotton mill workers with the courage and tenacity to confront the authority of the mill owners. Our greatest challenge, we realized, was to keep the newsreels from defining what is history.

We wanted to find the people who were in the old footage. We wanted to know what those times were like from their point of view, from the other side of the newsreel cameras. So, armed with the Movietone videotape, a VCR, and our camera, we went to some of the towns that we saw in the outtakes. We hoped the people in the film would help find their friends, their union brothers and sisters, and perhaps even themselves.

We brought our camera crew to Newnan, Georgia, where one of the most dramatic newsreels showed National Guardsmen arresting 126 strikers and imprisoning them for a week at Fort McPherson. At first, however, we couldn’t find any surviving strikers in this mill community brimming with retired workers. Then three sisters from the East Newnan mill village, retired spinners who “went to work” during the strike, identified Etta Mae Zimmerman among the “outsiders” who had come from towns as close as seven miles away to help the union local in Newnan shut the mill down.

We found Etta Mae in nearby Hogansville. “I’m not ashamed of being there, ’cause I didn’t do nothing that was so terrible,” she said as she watched the newsreel. “Nothing except join the union.”

We learned from Etta Mae that the union community in Newnan had been scattered — banished from the mill villages, or even from the town, by blacklisting. The few townspeople we were eventually able to find who had been members of the local were bitter about a labor uprising that had cost them their jobs, got their families evicted, and ostracized them from their community. Many had told no one — not even their own children — of their part in the uprising. Many remained unwilling to discuss their actions over half a century later.

We realized that the fear and silence would have to be a key part of our story. Not only would our film have to counter the simplistic newsreel images equating unionism with violence, we would also have to explore how history is used — and misused — to keep workers divided and frightened. Making the film would mean opening old wounds and revisiting bitter memories. But it would also offer an eye-opening look at the complex relationship between the past and the present.

“Use This Cob”

As documentary filmmakers, George and I found ourselves in the position of interlocutors — bringing the physical evidence of unionism into the Piedmont towns where it had been forged and then forgotten. The trunk of our rental car was weighed down with proof: cardboard file cabinets, organized by mill and by state, filled with copies of letters from mill workers to the Roosevelt administration demanding that their rights as workers and citizens be protected. We also brought a file full of the only comprehensive collection of photos of the 1934 strike, owned by the Bettmann Archive in New York.

For many strike veterans, our visit was the first time that they had seen these pictures and letters, far removed from their communities both in distance and cost. For George and myself, facilitating a reunion between rank-and-file participants in the strike and the photos, letters, and newsreel footage that documented their struggles was the most poignant part of the project.

It seemed fitting that our best resources for finding strike veterans were the hundreds of Labor Board cases that union locals had filed over a half century before in a vigorous attempt to seek justice for blacklisted workers. We used these documents like phone books, tracking names through city directories from the years following the strike to the present day. At first, we were concerned that showing participants their names on documents from Washington, D.C. might make our project suspect. Instead, many people we interviewed were awed that their role in the labor movement had meant enough to be saved — and that the union had not “upped and left” them, as they had been led to believe.

This kind of document research was especially important in locating African-American strike veterans. To look at the photos and newsreels, one would think that black workers played no role at all. But a retired African-American mill worker from Gastonia made an obvious point: Blacks wouldn’t have taken part in a crowded public event like a Labor Day parade. If whites could be fired for joining the union and marching on Main Street, blacks could well be lynched. Some blacks formed union locals, and some white locals accepted black members. But much of the resistance by black workers took place outside the union, in letters to the government demanding equal rights under New Deal labor policies.

The documents also led us to retired textile workers who stood up to the arbitrary authority of the mill owners even though they did not belong to the union. One woman described how during the lean years of the early ’30s, her boss warned employees to cut down on toilet-paper use in the plant. In response, she and a friend from the spinning room hung a corn cob from the back of the commode with a sign that said, “Use this cob and save your job.” She took as much pride in this mild act of humorous protest as many who joined the union, broadening our notion of what it means to be part of a “labor movement.”

Our search for strike veterans and their supporters helped young workers learn about the historic uprising. A present-day mill worker in Honea Path had grown up thinking that “the union came in and shot people” — even though her father witnessed the events and knew that management deputies had killed the workers. Only when she read an article in the local paper about our film project was she pushed to ask her father what really happened in her town. “Here I am, 37 years old, and he never told me that,” she said.

Even though the strike was brutally put down and the workers silenced, for many the uprising was but the beginning of a long struggle for justice. We met people who have devoted their lives to the rights of working people who started out as local leaders during the strike, including Lloyd Gosset, a union activist in Atlanta; Eula McGill, a volunteer organizer in Alabama; Lucille Thornburgh, a local leader in Tennessee; and Sol Stetin, a textile worker who rose to national union president.

After filming for three years, we’re now in the midst of editing the film with Susanne Rostock, a visionary film editor. We hope to finish The Uprising of ’34 this summer and launch an ambitious campaign to put it to use as a resource for community groups, teachers, grassroots organizations, and unions.

But even before completing the film, we have seen the impact its message can have in Southern communities. At a Grassroots Leadership conference, organizer Charles Taylor read aloud from a list of local textile unions organized in North Carolina between 1933 and 1934. Workshop participants responded with amazement: “Not in my town!” “I can’t believe it!” “That’s the most anti-union town I know!” Thus a simple piece of paper challenged long-standing myths about the ability and desire of Southern workers to organize.

At a union summer school in Georgia, we showed footage of the funeral at Honea Path, and discussed how working people can reclaim the history of powerful organizing that lies behind the simplistic images of violence. Afterwards, a young worker stood up and recited a eulogy for the workers who were killed there.

“You died for me,” he said. “But I’m not going to experience your death as a loss of ideals and the failure of our struggle. Because we’re here now doing what we’re doing. And we wouldn’t be organizing here now if you hadn’t taken the stance you took. Thank you — you are not forgotten.”

Tags

Judith Helfand

Judith Helfand is an independent film and video maker based in New York whose credits include “The Uprising of ’34” and the newly released documentary “A Healthy Baby Girl.” This piece was excerpted with permission from the Organization of American Historians Magazine of History, Spring 1997. (1997)