This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

One morning in the summer of 1985, Edith Jenkins and 15 or 20 other African-American women were on the picket line, breaking off one rollicking version after another of “We Shall Overcome” and “Ain’t Gonna Let Nobody Turn Us Around.” Jenkins worked in a J.P. Stevens & Company cotton mill in Roanoke Rapids, North Carolina, the site of a landmark union victory some years earlier, but on this morning the women were marching not on their workplace but outside the office of the school superintendent.

Edith Jenkins knew it took direct action to change the system. She had worked at J.P. Stevens since the days when blacks, if hired at all, were relegated to the dirtiest, most hazardous jobs and passed over for promotions. She had supported the union during the organizing drive of 1973 and 1974, and saw what a difference worker solidarity and a union contract meant.

“The union taught me to stand up and exercise my rights,” says Jenkins, a handsome, heavyset woman with gold-tinted curls and a gold-capped front tooth. “And it’s something I teach everybody around me. Too many people want to just say forget it, but nobody hears you if you don’t make some noise.”

Edith Jenkins hadn’t always been so vocal. She was “raised up the hard way,” picking and chopping cotton on a farm in a black settlement outside Roanoke Rapids. She married in 1967, the year she graduated from an all-black high school. “Being around white people frightened some people, but it never bothered me,” she says. “You just learned when to keep your mouth shut.” Her husband worked for a white man whose friend was a J.P. Stevens supervisor. The man recommended Jenkins for a job. In those days, she says, “a black person had to know somebody who knew a white somebody to get on” at the mill. She started on third shift (midnight to 8 a.m.) as a ring spinner at the River Mill, one of seven Stevens plants in Roanoke Rapids.

Thanks to her union contract, Jenkins has worked for the past 10 years as a winder attender on first shift at the New Mill, the Roanoke No. 2 Plant. And thanks to the lessons she learned as a union member, she has spent nearly as many years as a watchdog in the school system in Weldon, a town of 2,500 that lies just east of Roanoke Rapids on the Roanoke River.

Jenkins became involved in the schools when the youngest of her three children was a student at Weldon Elementary. She served as PTA president and founded a fundraising group called the Athletic Booster Club. “We’re a poor town and a lot of parents couldn’t afford to send their kids to camp or to pay for team supplies.” In the mid-1980s, she became a member of the superintendent’s advisory board. The superintendent was a white man in a district where 90 percent of the students were black. “Our school system was at a standstill,” Jenkins re calls, “and a lot of us felt it was time for him to move on.”

The breaking point came when the superintendent fired three black administrators for reasons Jenkins considered suspect. That was when she told herself: “Edith, you got to take a stand.”

First she organized the picket line outside the superintendent’s office — “grown black women voicing their opinion” — and then she ran for the school board. She lost. And ran again. And lost. In 1992, on her third try, she won.

Today, sitting at the kitchen table in her comfortable mobile home, Jenkins reflects on her improbable entry into politics. “I’m a survivor,” she says. “You got to fight just to survive around here. That’s how we won the union, that’s how I won my school board seat. I didn’t get in just for the sake of being in politics; Lord knows I’ve got enough to do. I’ve always been concerned that so many parents just don’t take time for their children. They’ve got one strike against them being black and I kept running because I was determined to see they get a good education — at that age they don’t need a second strike.”

The Movie

This year marks the 20th anniversary of the election victory won by Edith Jenkins and her fellow workers at J.P. Stevens. Back then, Stevens was an industrial giant, the second-largest textile company in the world. It operated 85 plants, all but 22 in North and South Carolina, and it earned more than $1 billion a year from sales of sheets, blankets, towels, carpets, hosiery, and tablecloths. All told, Stevens employed 44,000 people, not one of whom were protected by a union contract.

From the time workers held their first union election at Stevens in the late 1950s, the company epitomized the worst of American business; as often as not attached to its name was the phrase, “the nation’s number-one labor-law violator.” The appendage followed the company everywhere, like a storm cloud. A dozen times the National Labor Relations Board ordered Stevens to “cease and desist” from unfair labor practices. Three times the company carried its resistance to the Supreme Court, only to lose each time. The tactics cost Stevens $1.3 million in back pay awarded to workers whom the company had discriminated against because of union activities.

The story of the union making its stand in Roanoke Rapids — of its sheer tenacity and unexpected triumph — became a celebrated parable of the American labor movement. The struggles of Crystal Lee Sutton, one of the Stevens workers fired for union activity, became the basis for Norma Rae, the 1979 film for which Sally Field won an Oscar for Best Actress. The movie ended with a union organizer driving into the sunset, accompanied by swelling music, having guided his troops to victory.

Nor was Hollywood alone in its optimism. Labor leaders hailed the victory as a giant step toward unionization of the textile industry, many of whose companies, Stevens included, had fled the North over the previous three decades to escape organized labor. The late Wilbur Hobby, the colorful president of the North Carolina AFL-CIO who stood sentry during the vote count at Stevens, proclaimed that the win meant “a new day in Dixie.”

“J.P. first,” he announced, “the textile industry second, and then the whole South.”

That prophecy never came to pass. Though the union also won representation at several other Stevens plants, the reverberations from Roanoke Rapids were felt only as tremors in textile strongholds across the South. The industry was changing rapidly, and workers soon faced widespread plant closings. Even in Roanoke Rapids, the invigorating air of victory evaporated quickly. For six years after the election, Stevens refused to negotiate a contract. By 1988, the year Stevens was swallowed in a leveraged buyout, only 10 percent of its workers were organized. Textile workers in North Carolina remained the least unionized in the country, and Southern industry as a whole was less than 15 percent unionized — no more than it was eight years earlier.

Despite such gloomy realities, the shop-floor victory at J.P. Stevens did have a profound if little-noticed impact. When cotton mill workers in Roanoke Rapids, black and white together, mobilized successfully against the town’s largest employer, they also triumphed over wider social and political forces a century in the making. Their victory broke the stifling paternalism that was as much a part of the mill town as cotton and peanuts and the sulfurous stench of the paper mill.

In those days, textiles dominated the region’s economy; in five Southern states, the industry employed more than a quarter of the labor force. Many of the mills were in isolated, insulated towns — “90-miles-from-anywhere” towns, as the people in Roanoke Rapids say of their own. In towns like this, there were few alternatives to working in the mills save starvation. The town, in effect, was a modern-day fiefdom. Many white workers were born in the company hospital, grew up in a company house, shopped at the company store. They called themselves “Stevens People.” They defined their lives as Stevens.

With their victory over Stevens, mill workers learned that they have influence — and that they can bring their influence to bear on the bossman. Perhaps no one appreciates this more than Maurine Hedgepeth, a weaver in the Rosemary Plant whom Stevens illegally fired for union activities in 1965. An engagingly blunt woman, Hedgepeth was out of work for four years, until the U.S. Supreme Court reinstated her with full back pay. “Just like the company tells you what they want for their products,” she says, “we learned we can tell them what we want for our labor.”

Equally important, union members have brought their organizing skills to bear on the community outside the plant gates. In Roanoke Rapids and in the surrounding towns of Halifax and Northampton counties, workers emboldened by their union victory have fought to reshape local politics, reform schools, protect the environment, and improve race relations. Organizing a union made them better citizens, and better citizens make for a better community.

“People learned by example,” says Edith Jenkins. “You learned you couldn’t do anything on your own, but if you got together and stuck together you could make a better life.”

The Company Front

After the union launched its nationwide boycott of J.P. Stevens products in 1976, a handful of workers in Roanoke Rapids formed an anti-union group called the J.P. Stevens Employees Educational Committee. In an effort to mobilize support to decertify the union, the group held rallies, picketed union meetings, and distributed T-shirts and bumper stickers urging fellow workers to “STAND UP FOR J.P. STEVENS.”

The Educational Committee’s ties to a vast and wealthy network of union-busting law firms and right-to-work outfits in North Carolina and beyond have been well documented. Now, for the first time, one of the committee founders has come forward to confirm what has long been suspected: that the impetus to form the group came directly from management, not from workers.

Royce Still is a tall, gravelly-voiced 55-year-old with thinning red hair and an ever-present cigarette. He grew up in New Mexico and arrived in Roanoke Rapids in the late 1950s as a teenage serviceman stationed at the Army radar base outside of town. He began working full-time for J.P. Stevens, as a weaver in the No. 2 weave room at Rosemary, in 1964.

When he started in the mills, Still knew nothing of unions. “Well, I knew one thing,” he says, reconsidering. “I knew that if you were for the union, and it was plainly known, your ass was gone.”

When a union election was held at the plant the following March, Still voted no. He later was promoted to supervisor, and eventually took a position as a loom fixer, the highest paying hourly job in the mill.

One day in late 1976, after the union-led boycott of Stevens products had picked up steam, Still’s department manager pulled him aside. The two were good friends, Still says. “We used to socialize together.” The manager, Jim Simmons, ran the No. 1 weave room at Rosemary, where Still worked at the time. “He told me this local lawyer would tell us how we could get rid of the union,” Still recalls. Simmons directed him and two other Rosemary fixers to Tom Benton, an attorney whose firm represented J.P. Stevens locally.

Benton could not legally advise Stevens employees on how to fight the union; it was against the law for the company or its representatives to promote anti-union activity. Instead, Still says, Benton referred him to an attorney in Raleigh named Robert Valois. Valois practiced with the firm of Maupin, Taylor and Ellis, one of whose partners was chief political strategist for Senator Jesse Helms and head of the ultra-right-wing National Congressional Club.

Valois took over from there. He organized the Stevens Employee Educational Committee, advised the group on strategy and legal implications, hired a professional union-buster as its administrator, and inserted Still and two fellow loom fixers, Gene Patterson and Wilson Lambert, as the committee’s officers.

Stevens disavowed any connection to the committee. “We had nothing to do with organizing this movement,” a Stevens spokesman told The New York Times. “It popped up like a mushroom on its own.”

Although Still says he had no particular grievance against the union, he went along with the committee because his boss asked him to. “If nothing else,” he says, “I figured it was pretty damn good job security.”

In recruiting some of its top-paid employees to serve as a pro-company front, Stevens tapped a genuine strain of anti-union sentiment in the mills. Gene Patterson, a genial, barrel-chested man who grew up in the mill village and whose entire family worked in the mills, embodies the strain. “My mama was a bosslady at Fabricating and she was always against the union,” he says. “I guess I learned something from her.”

Patterson, 46, recalls watching a union demonstration in 1977 outside the Stevens Tower headquarters in New York City. “I was listening to some Catholic bishops make speeches supporting the boycott. And afterwards I told them that boycotting Stevens means boycotting our jobs. I said you need to be in church teaching people right from wrong, instead of trying to cause me to lose my job.”

By 1979, Patterson concedes, the Educational Committee had dwindled to a few true believers. “I was the chief and one day I looked back and there weren’t no injuns behind me,” he says.

Royce Still was no longer among the faithful. He quit the committee the day he learned Stevens planned to withhold annual raises in Roanoke Rapids while awarding raises in its nonunion plants. “That kind of pissed me off a little,” Still allows. The following Sunday, he attended his first union meeting. “When I walked in, I saw I knew a helluva lot of people in there and not one of them gave me a hard time.”

Still signed a union card that day. He started dropping by the union hall regularly on the way to work. After the contract was ratified, his fellow workers elected him second-shift shop steward in the Rosemary No. 1 weave room. Today he is president of the Rosemary Plant local.

— W.A.

The Potato House

To understand how far Stevens workers have come, it helps to know where they started from. It helps to visit the Potato House.

Heading down the flat ribbon of Interstate 95, a dozen miles or so beyond the Virginia border into northeastern North Carolina, you cross the Roanoke River. If you exit there, negotiate your way west past the motels and factory outlets and golden arches that bring traffic to a crawl, turn north toward town, past still more purveyors of chicken-and-biscuits and auto parts and barbecue joints (“We Serve No Swine Before Its Time”), you enter the heart of Roanoke Rapids, a city of 15,000.

The Potato House is a ramshackle, wooden building three blocks west of the intersection of 10th Street and Roanoke Avenue, the city’s main commercial thoroughfares. The whitewashed structure stands amid an open field in the redbrick shadow of the Rosemary Plant. Decades ago, when the mill company owned the houses, millworker families brought their potatoes to the little building for storage. Today it is home to the Boy Scouts, but older residents still call it the Potato House.

On a summer evening 20 years ago — August 28, 1974 — the Potato House was packed with officials from J.P. Stevens and the Textile Workers Union of America (TWUA). They were waiting for ballots to be tabulated to see if 3,500 Stevens employees in Roanoke Rapids had voted to be represented by the union.

Workers trying to join the union had been fighting illegal company tactics for 15 years. The TWUA lost two elections badly in Roanoke Rapids, in 1959 and 1965. The union challenged the latter election, charging that the company violated pre-election labor laws. The National Labor Relations Board agreed and called for a new election. Rather than begin a new campaign directly, though, the union waited while charges of unfair labor practices wound their way through the federal appellate system. Finally, in 1973, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit reinstated fired workers, directed the company to grant the union access to plant bulletin boards, and required Stevens to formally apologize to its employees.

During the long delay the demographics of the mills changed dramatically, and for the union, favorably. In 1965 almost all the workers were white. By 1973, 40 percent of the Stevens workforce in Roanoke Rapids was black. They came largely from outside the city limits: from the rural areas of Halifax and Northampton counties. Blacks were not indoctrinated in mill culture the way whites were, had not grown up under the company’s paternalistic wing. Many saw the union as their best hope for equal opportunity.

“I’d been there seven or eight years,” recalls Bennett Taylor, a black man who would become a union leader, “and I was tired of seeing people come in off the street and getting promoted and I wasn’t moving anywhere. I figured this was my chance.”

The new union drive began in the spring of 1973 when a TWUA organizer telephoned Joe Coyne, a paperworker in Roanoke Rapids and the president of United Paperworkers International Local 425. “The organizer asked me to help leaflet the Stevens plants,” recalls Coyne, who is 59 years old and has a full head of curly rust-colored hair turning to gray. His native New England accent clings to his speech despite having lived in Roanoke Rapids for 35 years. Coyne understood the need for organized labor. As a young man, he witnessed the shoe and textile industries desert his home state of Massachusetts, and then, in his adopted hometown, could see with an outsider’s clarity the power and powerlessness inherent in a company town.

The TWUA man told Coyne the union would gauge interest in an organizing drive by simultaneously distributing leaflets and return cards outside seven Stevens plants in Roanoke Rapids and a dozen or so in Greenville, South Carolina. “Whichever we get more cards back from, we’ll run the campaign at,” the organizer told Coyne.

The response from Roanoke Rapids was heartening. Some 350 Stevens employees — 10 percent of the local workforce — returned cards. Coyne heard again promptly from the TWUA man, who said, “We’re sending an organizer to town named Eli Zivkovich. He’s an ex-coal miner.” Coyne introduced Zivkovich around town, accompanied him on his first house calls, and provided him with a key to the paperworkers’ hall. It was there, in April of 1973, that the textile workers held their first meeting in Roanoke Rapids in eight years.

In June of the following year, Coyne was in Washington on paperworkers’ union business when he ran into George Meany, the fabled AFL-CIO president.

“We’re gonna win that Stevens election,” Coyne promised.

“Good,” Meany replied. “Then we can organize the South and you can send us some good politicians.”

Two months later, on the Wednesday before Labor Day of 1974, as the government oversaw the balloting, the Potato House and the surrounding field were thick with anxious onlookers: union and company lawyers and officials, workers, reporters. And elsewhere, in corporate boardrooms and union halls throughout the country, corporate executives and rank-and-filers alike awaited word of the results. Joe Coyne proved himself a fine oracle. Stevens workers voted 1,685 to 1,448 in favor of the TWUA.

The Corporate Campaign

But the fight for a union contract had just begun. TWUA membership in the North had been declining for years, and by the time of the upset win in Roanoke Rapids, the union was on its last legs financially. To make matters worse, Stevens stonewalled contract negotiations, refusing to even discuss such basics as grievance arbitration and automatic payroll deductions for union dues.

To avoid bankruptcy, the TWUA merged with the Amalgamated Clothing Workers of America. At its founding convention in June of 1976, the new 500,000-member Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union came out swinging. ACTWU authorized a nationwide consumer boycott of J.P. Stevens products, earmarking millions for new organizers, new court challenges, and a sophisticated public relations campaign.

Celebrities lent their star power. Jane Fonda came calling on the outspoken Maurine Hedgepeth. Gloria Steinem dropped in, and Mike Wallace and crew filmed a 60 Minutes segment. Boycott support committees, studded with academic, political, and religious luminaries, sprouted around the nation. Retirees, crippled by brown lung and denied a pension despite a lifetime in the mills, demonstrated outside Stevens Tower, the company’s 43-story headquarters in New York City.

Yet Stevens still refused to bargain in good faith. In 1977, an administrative law judge found that the company negotiated “with all the tractability and openmindedness of Sherman at the outskirts of Atlanta.”

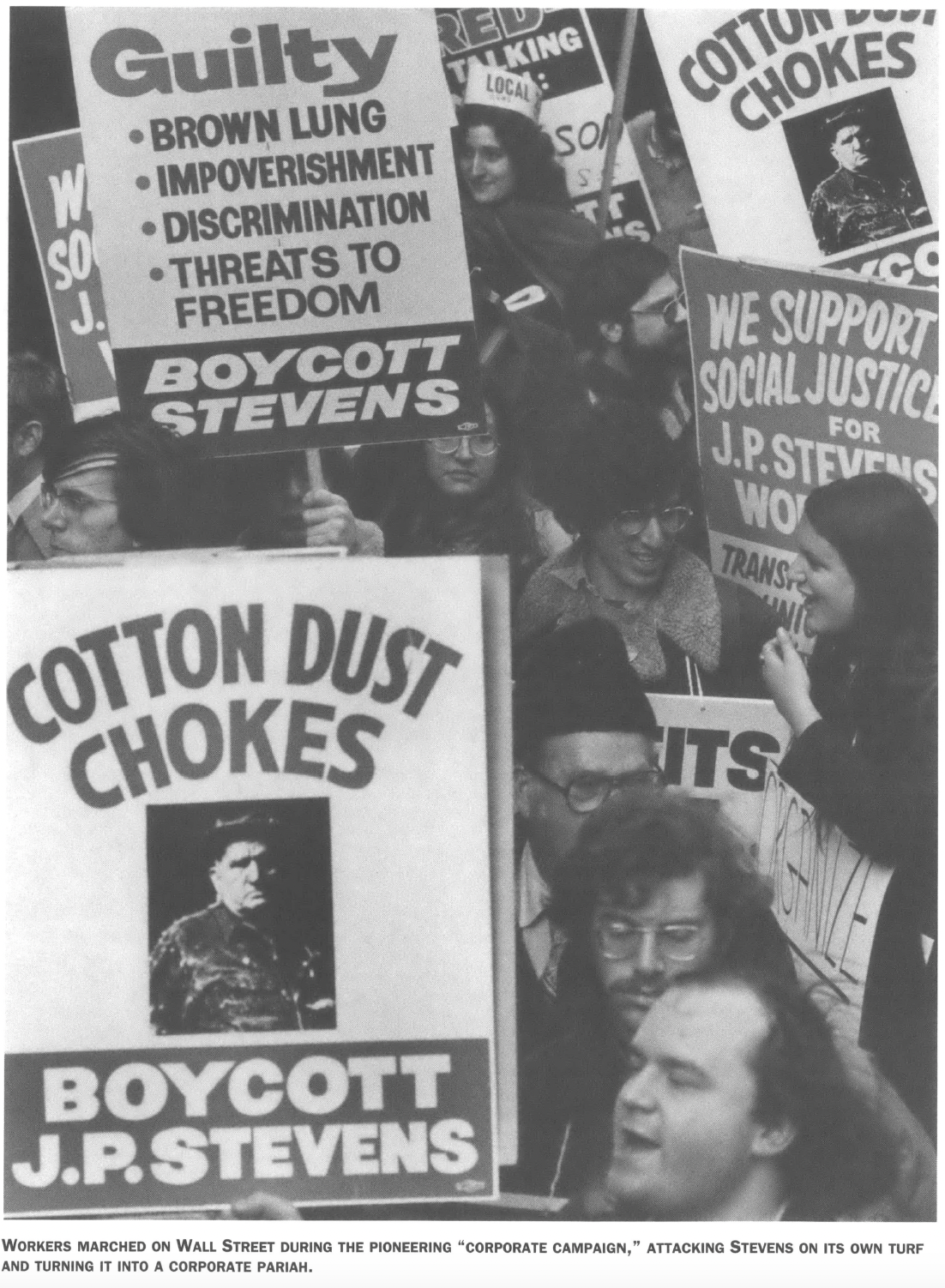

The blow that finally felled Stevens was the pioneering “corporate campaign” organized by the union. The campaign attacked the company on its own turf, in the board room and on Wall Street; it made Stevens a corporate pariah. The campaign successfully pushed two other corporations to oust Stevens’s chief executive, James Finley, from their boards, and forced two of Stevens’s outside directors to resign for fear their own companies’ reputations would be tarnished.

Stevens ultimately buckled under pressure from its financial houses. The union threatened to withdraw pension funds from banks allied with Stevens. And it vowed to run a dissident slate of directors for the board of Stevens’s largest lender, Metropolitan Life Insurance Company. The proxy fight would have cost Met Life $7 million; the insurer told Whitney Stevens, president of J.P. Stevens, that it was time to settle with the union.

A truce was soon declared. On October 19, 1980, 2,800 union members, meeting in the Roanoke Rapids High School auditorium, unanimously ratified the agreement with a stirring voice vote. In an adjacent science classroom, converted for the occasion to a press briefing center, Scott Hoyman, executive vice president for ACTWU, struck the same optimistic notes as had Wilbur Hobby six years earlier.

“For too many years,” Hoyman told reporters, “hundreds of thousands of textile workers have been treated to unlawful and repressive retaliation for daring to join a union, or in fact even showing sympathy for the idea of organizing a union. We are convinced that the Stevens agreements mark the beginning of the end of that unattractive chapter in America’s industrial history.”

The 30-month contract certainly meant new protections on the job, chief among them a grievance procedure with access to binding arbitration. “Used to be,” says Clyde Bush, the union’s longstanding manager in Roanoke Rapids, “if you had a gripe, hell, you told somebody, but there was never nothing done about it. If the boss wanted to fire you, he fired you.”

Under the contract, union members also elected shop stewards for all departments and all shifts. Maurine Hedgepeth was elected first-shift steward in the Rosemary No. 1 weave room. “People used to go in the bossman’s office one on one, and whatever the bossman said — or didn’t say, but said he said — went,” she recalls. “But now you’ve got protection: You can say what you want to and you don’t have to go in there alone. I think that’s what people like the best.”

The contract provided for a full plant-wide seniority system, union representation on health and safety committees, and regular renegotiation of wages and benefits. It also raised average hourly wages from $4.30 to $5.50 and provided for back pay denied workers during negotiations.

But the settlement had its price. It required the union to drop a $12 million lawsuit accusing Stevens of conspiring with police to spy on union organizers. The union also called off the boycott and corporate campaign, and agreed to no longer single out Stevens as its “primary organizational target.” The company, in turn, made no such promises. In announcing the settlement, president Whitney Stevens vowed to continue opposing the union.

Clyde Bush of ACTWU was unsurprised. “This company has been at war with the union for nearly 20 years,” he said at the time. “I don’t expect that to change overnight.”

The Ballot Box

But some things had already begun to change. Black and white workers had fought side-by-side during the union campaign; for most, it was their first experience with bi-racial cooperation. Before long, their new-found solidarity began to make itself felt outside the mills, permanently altering the racial landscape in the Roanoke Valley.

James Boone went to work for Stevens as a stockman and checker at the Delta Four Plant in 1971, the year after graduating from Gumberry High School in Northampton County. In 1973, when Eli Zivkovich leafleted the plant gates and invited workers to the first union meeting, Boone was there. “I looked at it this way,” he says. “It couldn’t hurt.”

Boone had had little contact with whites until he started at Stevens. But he understood that the union needed to reach out to white workers, especially the younger ones, if the fledgling movement was to succeed. “We built a coalition, because we knew we needed everyone to pull this off,” says Boone as he relaxes between meetings in the union office. He speaks in a slow and thoughtful manner, and has a goatee and mustache. Except for wearing his hair close cropped instead of in an Afro, his appearance has changed remarkably little in 20 years.

“You bring a group of blacks and whites together, with the same agenda, and it’s hard to break them up,” says Boone. “Our generation was more receptive to one another, and I think that surprised the company, because they were trying to divide us. But we had a foundation that couldn’t be shook. I used to tell people we all have families we’re trying to support, and if we’re gonna get anywhere we got to walk down the road together.”

Boone became a leader of the organizing drive, served on the union’s first negotiating committee, and in 1980 was elected the first president of the Roanoke Valley Joint Board, the congress of locals from the seven plants. He left the shop floor in 1988 to work full-time for ACTWU, and now serves as the union’s business agent in the Roanoke Valley.

Boone and other workers soon put their coalition-building skills to work in other arenas. They began their political activism by registering their neighbors to vote. “I didn’t know what politics was till I joined the union,” Boone laughs. Between 1974 and 1984, voter registration in Halifax and Northampton counties increased by more than 25 percent, while registration among minority residents jumped by nearly 60 percent.

In 1975 the union formed a committee to screen candidates for local and state offices. But because most politicians were beholden to the mill company, they were reluctant at first to court organized labor’s vote. “We’d send them a letter inviting them to a screening, and we’d get a letter back saying they were committed somewhere else and couldn’t come,” recalls Clyde Bush, the manager of the ACTWU local. “That happened all the time.”

With the contract came credibility. Politicians and business people gradually and, in some cases, grudgingly, accepted that the union was in town to stay. Joe Coyne, then-president of the paperworkers union and chair of the Roanoke Valley Central Labor Union, says the Stevens contract gave labor a prominent voice. “Now if some issue or a bill or a candidate comes up we oppose, I can say, ‘I’ll show you 3,000 people who don’t like it — and that ain’t counting their families.’”

In 1982, a young lawyer named David Beard announced his candidacy for district attorney. Beard was challenging the incumbent, Willis (Doc) Murphrey III, a Roanoke Rapids resident known less for his legal savvy than for his inheritance and his house: It was the largest in town. Murphrey was also known for cronyism; he was reputed to grant dispensations for favored defense lawyers, who in turn rewarded him at election time with generous contributions.

So David Beard worked the grassroots. He sought the support of community organizations, black and white churches, the Central Labor Union. He promised to “play fair,” to rid the judicial system of the old-boy network, to hire qualified minorities as assistant district attorneys. And people responded. With the help of the textile workers, Beard won 60 percent of the vote. After Beard’s victory, Joe Coyne says, “the politicians came looking for us.”

The Incinerator

Progressive coalitions, spearheaded by union members, have also helped elect their own to local offices. Linwood Ivey, an ACTWU stalwart who served on the union’s first negotiating team and was vice-president of the Fabricating Plant local, served two terms as mayor of the Northampton County town of Garysburg. When he died in 1991, he was succeeded by Roy Bell, a former shop steward and vice-president of the Delta Four Plant local.

Bell says that his union activism, particularly his work as a steward representing grievants against Stevens, helped prepare him for public life. “I learned how to sit across the table from people and talk confidently, and I learned how to really read a contract. As a public official, you have to talk to people all the time, have the confidence to sell your town to industry.”

Union members have also fought for groundbreaking laws. In 1983, the Central Labor Union introduced a “Right-to- Know” ordinance for Roanoke Rapids. The ordinance would have required industries to warn workers and the community of health risks related to toxic and hazardous substances. There were similar ordinances in effect in larger cities in other regions, but this would have been the first anywhere in the South. A mayoral study committee approved the ordinance in early 1984, but the city council, whose most influential member was a retired Stevens executive, voted it down.

A year later, union members joined other activists to push the region’s first Right-to-Know law through the North Carolina legislature. Joe Coyne, who also chaired the N.C. Occupational Safety and Health Project, was a “major mover” behind the legislation, says Susan Lupton, an NCOSH staffer at the time.

A decade later, millworkers teamed up with local citizens to ward off another environmental threat. A company called ThermalKEM had announced plans to locate a hazardous-waste incinerator in Northampton County. The company had apparently cut a land deal with the county commissioners behind closed doors. When a public hearing was finally called, so many residents showed up to protest the plan that the commissioners canceled the meeting.

Out of the protest grew NCAP — Northampton Citizens Against Pollution. The group’s power sprang from its diversity. Among those on the NCAP board was James Boone, the ACTWU leader who learned about coalition-building from the union drive; the first proposed incinerator site was a half-mile from his home. Many other members of the textile and paperworkers unions belonged, as did black and white professionals, young people and grandparents. The county NAACP chapter, headed by ACTWU president Bennett Taylor, played a pivotal fundraising role. And District Attorney David Beard called for a state criminal investigation of the company. “We’re like a patchwork quilt,” an NCAP member told The Independent newsweekly. “We’ve got one seam holding us all together, and it’s the incinerator.”

The fight lasted three years. Millworkers and other voters used their power at the polls to oust town and county officials who supported the project, and in the fall of 1993, ThermalKEM withdrew its plans. NCAP had successfully drawn on the legacy of the Stevens campaign to defeat another industrial giant. “Just like when we started the union,” says James Boone, “we knew it had to be black and white together to keep the environment safe and clean.”

The Buyout

The political progress by union people has been matched by economic gains. Local merchants no longer shy away from labor — they are only too glad for the extra dollars the union puts in workers’ pockets. Hourly wages have increased substantially since the original contract, from $5.50 to $9.60 today. And retailers seem equally pleased with the credit union ACTWU initiated to help workers save money or make big-ticket purchases.

Even though the entire community has benefited from the presence of the union, the most powerful forces that shape life in Roanoke Rapids remain beyond the control of union members. The local economy, like that of much of eastern North Carolina, and indeed much of rural America, is largely controlled by outsiders. Much of the land is owned by absentee timber and paper interests, and most jobs are driven by Wall Street investors. The sober fact is that no matter how well working people organize, no matter how many voters register and elect progressive candidates, their economic life is still shaped by distant, often invisible, hands.

In the 1980s, as the takeover boom swept corporate America and financiers traded stock certificates in the mad pursuit of short-term profits, the consequences hit hardest in towns like Roanoke Rapids. Today, J.P. Stevens & Company no longer owns the mills; in fact, there no longer is a J.P. Stevens. The company, which began as a small wool flannel mill in 1813 in Massachusetts, fell victim to a corporate takeover fight in 1988. When a group of senior executives tried to stage a leveraged buyout of Stevens, they were outbid by one of their biggest competitors, West Point-Pepperell Inc.

To avoid antitrust problems in the $1.2 billion deal, the new owner split up Stevens’s 59 plants among itself and two partners, a Wall Street investment firm called Odyssey Partners and the Bibb Company of Macon, Georgia. Bibb’s share of the prize included the Roanoke Rapids division. Bibb itself is owned by a Wall Street leveraged buyout firm, NTC Group. NTC, says chairman Thomas Foley, is basically “a corporate staff structured to be able to execute acquisitions.”

If union activists don’t mourn the loss of their one-time corporate nemesis from a labor-relations standpoint, they do miss the company in other ways. “You can say anything in the world you want to about the Stevens company,” says Maurine Hedgepeth, “and their relations with the employees were the worst. But you’ve got to give it to them that they were good businessmen. They sold the cloth we made. Bibb is not doing that. I don’t think Foley knows what he’s doing. He’s a wheeler-dealer on Wall Street — that’s his business, not textiles.”

Because Bibb has no brand names of its own, the company is finding it hard to hold its market share. Last year, between Thanksgiving and Christmas, Bibb laid off 120 employees. Tom Gardner, the company’s chief executive in Roanoke Rapids, attributes the layoffs to “a seasonal decline in orders.” But Clyde Bush, the local ACTWU manager, connects the layoffs to Bibb’s lack of experience in textiles. “I think it was a pretty good shock to everybody, because it’s a terrycloth business, and those are usually running full-time this time of year.”

The layoffs were the latest jolt to a wretched economy. The unemployment rate of 6.5 percent around Roanoke Rapids is more than 60 percent above the statewide rate. And though the local rate is nearly half that of a decade ago, most of the jobs created in the last 10 years require no skills and offer no future. The names of Roanoke Valley residents who scrub toilets or cook fast food or sew piecework or bag groceries might not show up on unemployment rolls, but that doesn’t mean they are earning a living wage: More than 30 percent of persons working full-time in the area live below the poverty line.

More than a quarter of the households in Halifax County and 30 percent of those in Northampton earn less than $10,000 a year. African Americans fare even worse: Fully 40 percent of black families in the two counties earn less than $10,000 annually.

The crushing poverty affects everything from life expectancy to education. Babies in Halifax County are nearly twice as likely as other North Carolina newborns to die in infancy. And although students in Roanoke Rapids schools perform well on standardized tests, the area is also home to three of the statistically worst school districts in the state: Northampton County, Weldon City, and Halifax County.

The Non-Factor

None of this hardship is reflected in the glowing portraits of the area painted by the Roanoke Valley Chamber of Commerce. “It has often been said that education is the key to a brighter, more successful future,” the chamber boasts in one of its slick booklets, “and the Roanoke Valley boasts one of the best school systems in North Carolina.”

Nor does the business community reflect much of the progress in race relations fostered by the union. Another chamber brochure touts the county’s “many antebellum plantation homes, several of which have been restored to their original splendor. These gracious old homes are adorned with . . . hand-carved features, most made by local black artisans.”

“Those ‘artisans’ were our slave ancestors,” says Gary Grant, a community organizer in rural Tillery who helped defeat the ThermalKEM incinerator. “And while tax dollars go to restore those houses, low-income housing funds are unavailable and many African Americans are still using outhouses.”

While promoting the “tranquil lakeside atmosphere” and “friendly people” of the area, the chamber and other industrial boosters prefer to ignore the community benefits of organized labor. A pamphlet put out by the Halifax Development Commission, for example, reminds prospective employers that “North Carolina is a right-to-work state” and boasts of the Roanoke Valley’s “business climate.”

According to L.C. (Rocky) Lane Jr., executive director of the commission, most industrial scouts inquire about local “union activity.” “It’s a standard economic development question,” he says, “not unlike the availability of natural gas or water.” Lane recalls one company representative who “flew in here, checked the Yellow Pages, found unions, and boogied right on out.”

Not every official cringes at the specter of unions. Lloyd Andrews, who stepped down last year after a decade as mayor of Roanoke Rapids, considers ACTWU a “non-factor.” Andrews is 65. He has white hair, a creased, open face, and a politician’s ready smile. He grew up in a mill house near the Patterson Plant, where his father was a supervisor. “The union has had no effect on this community,” Andrews says flatly. “It was the news media that came in from somewhere else, took a little something, and blew it out of proportion.”

Andrews blithely dismisses further questions about the impact of the union, preferring to address the beneficence of the mills. When Bibb purchased the Stevens softball fields near the Fabricating Plant, he says, the company donated them to the city. “One year we were having financial problems and we asked Stevens to pre-pay their taxes, and they did it without hesitation,” he adds. “I consider both Stevens and Bibb good corporate citizens.”

Asked about the biggest problem facing the city, Andrews pauses, gazing out the window for a moment. “Absolutely number one,” he says firmly, “we’ve got to raise the money to build a new city hall.”

Andrews seems untroubled by the city’s uneven economic development during his tenure as mayor. On the almost all-white east side is the Becker Farms subdivision. There, spacious homes on wooded lots line new roads and cul de sacs. Nearby are a private health club, condominiums, and Becker Village Mall. In the black neighborhoods on the west side, meanwhile, are unpaved streets and shacks with rusted, sagging roofs, some without indoor plumbing. Many homes have chronic flooding problems, rotting floors, and faulty wiring. Asked about the reasons for the disparity, Andrews replies: “I don’t know why.”

The Lint-Heads

Twenty years after the union election, the Potato House is quiet, save for the occasional raucousness of Boy Scout meetings. The union and company agreed early this year on a new 30-month contract, the fourth since the 1980 settlement. The relatively peaceful negotiations were held in a conference room at the Holiday Inn.

These days there is little contentiousness — too little, say some. Several activists complain privately that the union has grown complacent, that it has become too cozy with the company and is too quick to settle grievances. The union is an established and generally welcome part of the community. It endorses political candidates, sponsors community events — even enters a float in the city’ s Christmas parade.

“Prosperity has been our downfall,” says a union officer who asked for anonymity. “People make more money now and they’ve got a good grievance procedure and that’s all they care about. They forget about what it took to get here. Sometimes at meetings for all five locals we don’t have 20 people — sometimes the officers don’t show.”

Even the staunchest critics, however, acknowledge that the union dramatically shifted the balance of power in the community. That Stevens workers managed to exercise the most basic right of labor — the right to organize — in the most hostile of environments has imbued them with a dignity and confidence lacking in earlier times.

Maurine Hedgepeth remembers those earlier times. Her parents worked in the mills, and during 1934, the year of the General Textile Strike, when Hedgepeth was two years old, they invited the first textile organizer in Roanoke Rapids to live with the family. Her parents took Maurine to her first union meeting when she was 16. Three months after her second child was born, when she was 23, Hedgepeth went to work in the mills as a magazine filler. The following year, 1956, Stevens bought the plants.

“People who worked in the mill used to be looked down on,” says Hedgepeth, who at 62 and nearing retirement remains a firebrand. “I’ve always felt like I was somebody, but there are a lot of people who didn’t. They used to call us names — lint-heads, lint-dodgers. We made less money than anyone else. Organizing changed all that. Organizing is taking a person who thinks they’re nobody and giving them the courage to stand up and fight. That’s organizing. That’s what the union here did.”

Tags

William M. Adler

William M. Adler lives in Austin, Texas. He is at work on a book about Universal Manufacturing. Research support for portions of this article were provided by the Dick Goldensohn Fund and by Carol Bernstein Ferry. Spanish translation by Christina Elena Lowery. (1998)