This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

The following article contains anti-Black racial slurs.

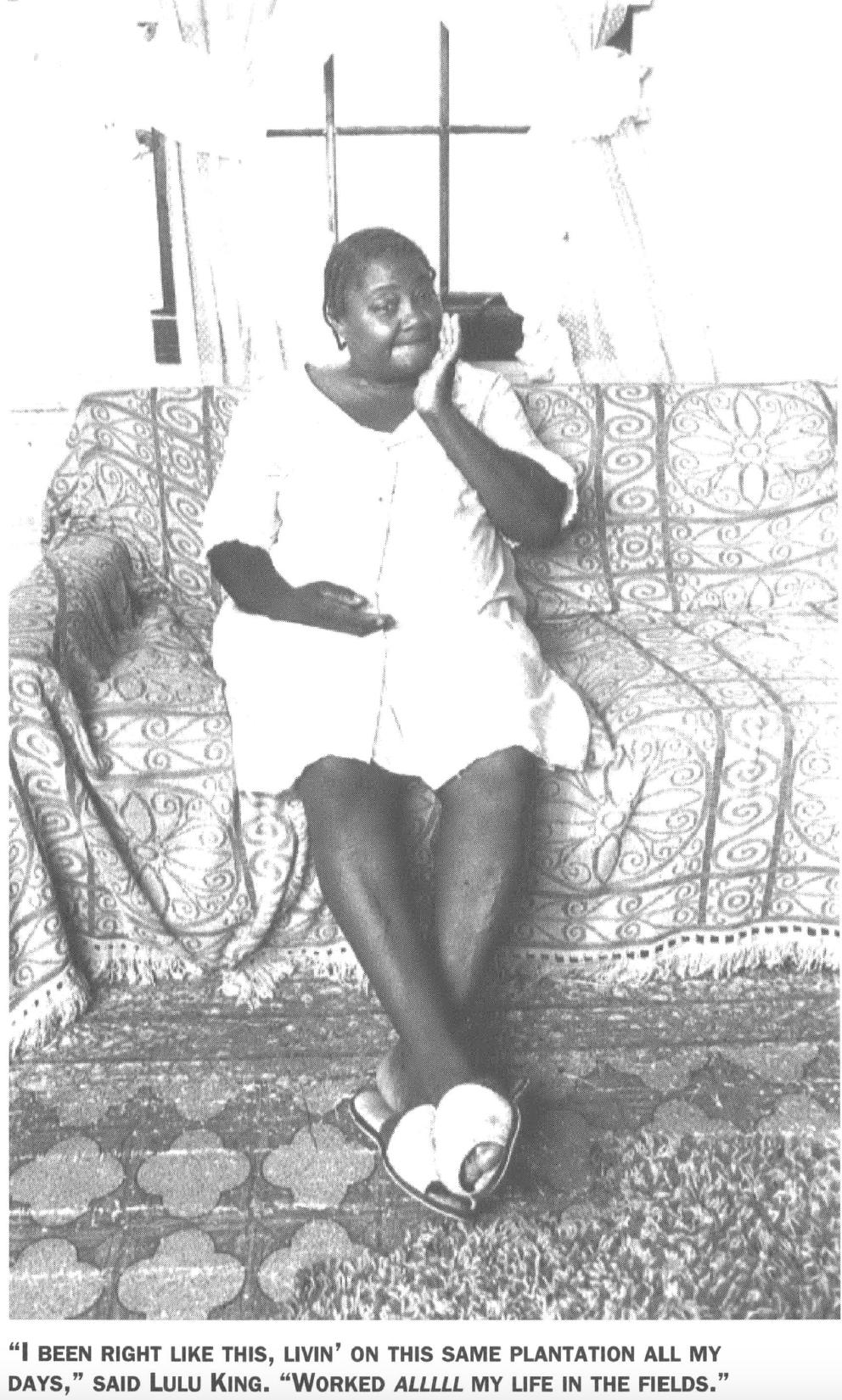

Editor’s note: When journalist Patsy Sims published Cleveland Benjamin’s Dead in 1981, she provided a devastating look at the struggle for dignity among sugar cane workers in Louisiana. In June, the University of Georgia Press will publish an expanded edition of the book featuring material cut from the original. One previously deleted chapter includes an oral history of Lulu King, who worked on the sugar plantation her entire life. Sims visited her in 1972.

The shortcut to the home of Joyce Hadley’s grandparents was really just two ruts cut by tractors driving back and forth through the fields. If you followed it a mile or two in the opposite direction, it led to Coulon Plantation, where her father, a brother, and her other grandfather lived, and where, until two years ago, it seemed she too would spend her life. But at 18 she had married, moved with her husband and year-old son into a house that had hot and cold running water, and found a job with the Plantation Adult Education Program as a liaison between the staff and the fieldworkers, building a trust between the two.

“Long as I can remember, my grandfather’s been working on one plantation or another — Orange Grove, Coulon, Rienzi, where we’re on our way to now,” she recalled as the car bumped over the muddy road. “He can’t work anymore, but my grandmother works for the owners so she can hold the house. She gets paid something like $20 a week. She milks cows, cleans house, irons, babysits, stuff like that.”

As the workers’ houses loomed larger, as we neared Rienzi, Joyce’s frustrations mounted. “It’s a cycle,” she said. “My grandmother lives here, an’ she has two sons an’ a granddaughter here. They all live here in their own houses an’ work. One son is 39 an’ another is 24. The granddaughter is even younger, about 20. There’s a daughter living with ’em too, during grinding. They just don’t get off. It’s just ‘Mama did it, an’ if Mama could do it, it’s good enough for me.’” She sighed. “Mostly, it’s being afraid. It’s hard enough living here. Just think about going into town where you have to pay rent. That be just one more bill you have to worry about.”

We turned onto a dirt-and-gravel road that led to the houses, some of them painted and in better condition than most I had visited. An old man waited eagerly in the doorway of one, his grin widening as we neared the house, and him. At 63, Willie King was lean and stooped, his chin spiked with gray, his voice husky and worn out, yet his spirit seemed unbent. As he recalled the past, he chuckled often — the way so many plantation people did, as though humor was their answer to a difficult life. After we were introduced to him and his wife, Lulu, he relaxed in a rocker, contented as we talked.

“I worked on the plantation 30-some years,” he said. “I butchered till I was 30, till I start workin’ in the fields. That was in ’28, somethin’ ’round then. It was hard work, yeah.”

He rocked and chuckled good-naturedly.

“Why did you leave the butcher’s and come to the plantation? The pay wasn’t very good, was it?” I asked.

“Well, I jes’ did. ’Round town, things was so tough. It was the Depression, you know.”

I asked how much he made when he started working in the fields, and he chuckled again. “I don’t wanta tell you no story — we was gettin’ 80 cents a day. Then we got a raise, we got a dollar a day. An’ after that, we got a dollar ten cents — the price is goin’ up, li’l bit, li’l bit,” he said, his voice rising with the wages. “An’ after that, we got a dollar an’ 20 cents. Well, that stayed until Governor Long win — the first Long — an’ he raised us to a dollar an’ a half. He cut all them long hours, from dark in the mornin’ to dark at night, an’ start payin’ a li’l bit more, but they kilt him. Then they start us off at 20 cents a hour, an’, well, it jes’ kep’ on up, kep’ on up till where it is now.” He fell silent, and when he resumed there was disappointment in his voice. “But now they makin’ more an’ I can’t get none a it.”

He and his wife had raised 12 children. Now the two of them and a grandson lived on the $115 Willie received from Social Security, plus another $24 he got from “old age” and the $24 Lulu made babysitting and keeping house. Rent came free, but still there were the utilities to pay for.

“I tell ’em that’s all I’m workin’ for is gas an’ water’ an’ medical bills,” Lulu said good-naturedly. That and the house was why she kept going. “When you ain’t able to work,” she explained gravely, “they put you out.”

Two women in yellow rubber overalls and jackets entered the house and edged up to the gas heater. Joyce introduced the older one, in her mid-30s, as Aunt Golena; the younger, 20, as her Aunt Lois. Even with layers of sweaters and slacks and the rubber overalls, the women shivered and Golena complained, “That wind go right through you!”

“What do you do?” I asked.

“Scrap cane behind the cutter,” she answered.

Willie King interpreted simply, “That’s when you foller the cutter an’ pick the cane up an’ throw it on the other side a the road where they be puttin’ it at.”

Golena warmed her hands over the heater. “Rest of the year I do housework,” she explained, “but durin’ grindin’ I can make more money in the fields. I make but $6 a day cleanin’, an’ durin’ grindin’ I clears about a $157 ever’ two weeks.”

“The womens get the same price as the mens! They get a dollar eighty cents a hour! Now that’s the common labor like I was!” Willie King shook his head with finality. “An’ I can’t get none a it. I worked till last year but my legs give out an’ my wind got short — I jes’ couldn’t make it no more.”

Lulu King crossed her swollen ankles as she rocked and reminisced. She had never been more than an hour and a half away from home, no farther than her ancestors had ever traveled from Rienzi after the first one came as a slave. Once a month she made a trip to Charity Hospital in New Orleans and back — always back, as though a giant magnet was pulling her, as it had her parents and, even now, her children and theirs. One time she would have liked to see outside Louisiana, what the world was like, to see it or to read about it. But now, she reckoned, she had “done got too ol’.”

A large woman, her face fatly wrinkled, her eyes still bright with hope, she sat rocking and watching the red-faced Pepsi-Cola clock over the doorway and, through the window, the dirt road that led past the house where she was born and into the fields.

“That’s the time I use’ to always pray, when I was out in the fields. I could talk to Him better. Wouldn’t be nobody to bother me, an’ I could ask Him to save me an’ to he’p me keep on agoin’. When I got religion, it was out in the fields. Them same fields right outside the window. It was in 1922, on the 17 day a May when I was 13. I never forget that day. Look like it was a daaaark road wit’ a fork in it. One road goin’ this-a-way. One like that. A voice, a hymn, was acomin’ to me, singin’ ‘Poor Mona Got a Home at Last.’ Seem like the mo’ I’d get to that fork, the mo’ that voice’d come to me. There was a biiiiiig man standin’ in the middle a that road, so I said to him, ‘Mister, could you tell me which-a-way to find Jesus?’ He say, ‘Go this-a-way.’ But look like somethin’ say to me, ‘No, don’t go that-a-way.’ So I went t’other way, an’ look like the more I’d go up that road, the bigger that light would get. When I got to the end of that road that light, look like it jes’ lit up the whoooooole world. An’ then that hymn jes’ come out, ’bout ‘Poor Mona Got a Home.’ I don’t know how I didn’t feel. I jes’ felt light. I was happy. I was cryin’. An’ then I got baptized that third Sunday in July up there at the church on Main Street. It was a pool at the back a the church, an’ we all was in white. An’ well, look like religion what kep’ me goin’ all these years. The he’p a the good Lawd, that what he’p me to make it. They say the Lawd always makes a way, so I didn’t see no harder day in my 60 years than what I’m seein’ now.

“I been right like this, livin’ on this same plantation all my days. Born last house down the street. It’s no more fittin’ to live in now, but that’s where I was born an’ where me and King got married. Ever since I knowed, my family was on this plantation, till 15, 20 years ago — till they move, they scattered an’ moved away. They all was cane workers: Cut cane, ditch, plow with mules — like that. My mama was ’bout 60 when she stop. She jes’ fell down sick an’ had her kidney taken out an’ she never did work no mo’. My daddy worked till he died. He died when he was 59, but he worked alllll a it. He always did work mules. My grandfather did the same thing. An’ my great-grandfather — well, I reckon he did too, but I never did knowed him. Reckon he mighta been a slave. My chil’ren they be married an’ gone now, but they all did work on the farm at one time or ’nother. Start when they was 14 years old, most of ’em. Junius an’ Turner an’ Oliver, the one live next door, still do work in the fields, an’ two my daughters from in town come in durin’ grindin’ to scrap cane.

“I started workin’ when I was nine, ’side my mama. Worked alllll my life in the fields pickin’ up rice an’ scrappin’ cane, till this arthritis got me in the hip. Scrap cane, cut cane, cut rice, load rice, sack it up — done ever’thing. Now I can’t do too much. I’m not able. Jes’ some babysittin’ in town. An’ King he don’t work no mo’ neither. When I started in the fields it was eight of us in the family. Seven sisters an’ one brother. I was the oldest. We jes’ was poor. We didn’t have nothin’ an’ the chil’ren then had to work. They had a bunch a us kids workin’ on the place. We was workin’ for 40 cents a day. From five in the mornin’ till five at night. We’d work five days in the field, an’ the six we’d stay an’ clean up us house an’ wash the clothes. There was no time for playin’ in the fields. The boss man’d be on your back, an’ if you wouldn’t work, he’d whip you. I never was whipped, but I was afraid of ’im. At that time, colored folks wasn’t good as a good dog to the white folks. An’ they always was callin’ you a nigger. ‘Get out there, nigger.’ ‘Nigger, do this, ’n nigger do that.’ An’ you be scared to say anything. They never did hit me, jes’ talk rough, an’, well, I jes’ thought that was our name, nigger.

“All what money we made we would give to Mama, an’ on Sunday she’d give us a quarter. There was a nickel for me to spend an’ one to put in church, an’ if I had my monthly church fee to pay that was 15 cents. I thought I had aplenty with that nickel. After church we’d go to that fruit stand in town, an’ I’d buy me the most candy I could get. I’d buy me a biiiiiig peppermint candy ’cause it was mo’. It lasted longer. That be what I always got. My mind would be on it ’fore I’d get to that fruit stand. ‘Gonna get me a peppermint candy.’ Sometime we use’ to take the overripe fruit, them bananas an’ oranges an’ things that’d be rotten. We’d get a big pile for 15 an’ 20 cents. We jes’ come up so poor we was glad for anything we could get.

“I only had one Sunday dress I always wore to church. It was navy blue with little white star dots on it an’ lace on the collar. For the week I had different clothes, but never too many. Jes’ a change a suit. When one get dirty, we’d wash it an’ put it back on. Christmas, Mama use’ to buy us a doll an’ that was all we was gonna get till it was Christmas again. Only time I got a birthday present was when I was growed up an’ my chil’ren give me somethin’. Like when people celebrate their birthday, well, we never did when I was small. It jes’ was a day you knew you had but it wasn’t anything special. The week I married King I worked in the fields. I had 16 chil’ren. Raised 12 an’ the other four died. Out a all I had I only lost three wintertimes from workin’ in the fields — that’s the three born in October. That one next door, he was born New Year’s Eve day an’ I worked the day before that, out in the field cuttin’ cane.

“I would keep the older ones home to see to the little ones durin’ grindin’, an’ before the first one was big enough my sister’d mind ’em. It was hard workin’ an’ bringin’ up kids. I use’ to work all day in the field, come home an’ have to wash an’ cook. I use’ to bathe my child’ren an’ put their day’s clothes on ’em before I’d go to bed, ’cause I wouldn’t get up time enough in the mornin’ to dress ’em, an’ the older ones wasn’t old enough to put the clothes on ’em. They jes’ could keep changin’ diapers. Sometimes I jes’ sleep ’bout an hour then I had to get back up an’ go to work again.

“By me workin’ ’round white people, they use’ to always give me a little clothes an’ stuff for my chil’ren. An’ furniture, it was the same thing. All what I got was give me. Ever’time I wished for somethin’ the white folks’d come along an’ give me a little piece better than what I had an’ I throwed away what I had. I never bought nothin’ new but that stove an’ TV. Paid for ’em on time. An’, well, the TV’s so old now till it don’t even show the picture. Sometimes it goes out an’ it comes back again but I sure wish I could get one I could sit down an’ look at.

“We lived in one them ol’ houses cross the way till nine or 10 years ago when we moved to this one. First time I ever had a bathroom was in this house, when they put one in three years ago. Before that, we bathed in a tub. One of those wood tubs that be made out those barrels. Ever’ night we had to heat 14 tubs a water on the stove. Still do have to heats water but now it’s jes’ King and me. We used to have a shack out back, too. A little tin buildin’. Rain, snow, storm, anything else, you had to go outside. I remember it rained like I don’t know what in that ol’ house across the road. If it start rainin’, we had to get up from sleepin’ an’ start pullin’ the bed from under the leak. An’ jes’ like you see through that glass, you could see the road through the cracks in the wall. The rug on the floor, it be raisin’ up like I don’t know what. Plenty time we use’ to have to put rags on the floor to stop the col’ from comin’ in.

“Still, I reckon I rather go live back in that ol’ house than move in town. I been on the plantation so long till look like I ain’t gonna feel right if I ever get off. I know I’d miss it. All my life I been knowin’ these people. I likes it hyere. I knows it hyere. An’ I could go anywhere with my eyes shut. I don’t know. I never did like no town. I jes’ got that fear feelin’ ’bout it. Hyere we don’t have to pay no rent — an’ I worry ’bout that, ’bout havin’ to move to town an’ pay rent with the little bit a salary an’ security we get. Lotta time they make you move when you can’t work no mo’. But the boss tol’ me, ‘Lulu,’ he say, ‘if you wanta stay in there, stay. Jes’ keep it up. Keep the grass an’ the trash out the yard.’ An’, well, he ain’t never bothered me. I been knowin’ him an’ his wife both since they was babies. I lived in the house next to his mama. When they move on the place, the boss wasn’t big as this boy hyere, an’ I ‘Mister’ him. I ‘Miss’ his wife, too, Miss Caroline. An’ I got chil’ren older than what they is. But I always did ‘Mister’ ’em all. Look like it jes’ more manners to me. That’s jes’ my way. When I was comin’ up, you had to say ‘Yes ma’am,’ ‘No ma’am.’ Didn’t care who you was. If you didn’t, you jes’ was gonna get punished. Sayin’ ‘Yeah’ or ‘No,’ you was too sassy. Now they tell ’em anything they want, but I still say ‘Yes ma’am’ an’ ‘No ma’am’ an’ that’s how I taught my chil’ren. Even now, people I’m babysittin’ for they be after me to come sit to the table. But I’m so use’ to bein’ out in the yard — like a dog — I tell ’em all the time, I’ll eat when I get done doin’ my work.’ Look like I jes’ can’t make myself go sit down there with ’em. I tell ’em all time, I tell ’em, ‘I jes’ feel like a fly in a bowl a milk. That jes’ the way I come up. Not say I hate y’all or scorn y’all, but it’s jes’ the way I was brung up.’

“Sometime I sits down hyere now an’ thinks ’bout how white folks use’ to do us. When my chil’ren was growin’ up, there’d be a slavery picture on TV an’ I’d say, ‘The way you see those people, that jes’ the way we was.’ ’Cause in a way we was treated like them slaves. Not the way them people use’ to go buy ’em from different people an’ they couldn’t go from one place to another. We could leave on our own. If you didn’t like this place, you could move an’ go to somewheres else an’ stay, but it wasn’t no better. The boss man might treat you a li’l bit better than what the other man did but you might be in a worser house. There was really no place to go. Things was pretty much the same ever’where you went.

“I never thought I’d live to see things change like they did, the way white folks treat blacks. An’ I’m glad for my chil’ren they did, ’cause I reckon I be more worried. When they started goin’ to school together, that’s one thing I kicked against my chil’ren doin’ because I knowed how they treated us when the blacks wasn’t mixed up with ’em like that. I was scared. But it turned out awright. There’s some care more ’bout you. They treat you nicer than what the others do. Still, them what treats me nice I be scared. I don’t trust ’em. I think they be like the ol’ ones use’ to be. Because you got some of ’em, they hate you still. They cut your guts out if you ever walk ’cross their door. They got some right hyere in town now. I knoooooows of ’em. If you go an’ ask ’em for a drink a water, if you ain’t got a paper cup, they ain’t gonna give you no glass. If they give you a glass, they rather to throw it in the garbage an’ break it up to keep from puttin’ their hands on it. But I ain’t got nothin’ in me against ’em now. I forgive ’em what they did to me ’cause look like that jes’ the way they was livin’. I don’t regret that. In a way, I’m glad, because I never been in a jailhouse in my life. Never been on no witness trial. An’ I know how to go amongst the white folks. So I’m glad I lived that life I did ’cause I was out of trouble.

“To me, I had a good life. I was able to work, to get mostly what I needed — not what I wanted, but what I needed the baddest. An’ if the Lord’d wanted my life to be better, He would a made it better. Still, I talk to Him sometime, ’bout Heaven. I know I’m goin’ there. I’m fightin’ haaaard to go there. I thinks about it, an’ I asks Him to let my best day down hyere be my worst day there. I don’t know what’ll be up there. All I wanta do is be happy — be happy an’ sit down’n rest.”

Tags

Patsy Sims

Patsy Sims is the author of The Klan and Somebody Shout Amen! She is assistant professor and coordinator of the Creative Nonfiction Writing Track at the University of Pittsburgh. (1994)