This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

Like much of the textile and apparel industries, Kellwood Company was doing well a decade ago. In 1981, the St. Louis-based firm — which manufactures blue jeans, sportswear, and women’s lingerie for leading labels like Hanes, Nike, Adidas, and Sears — employed 16,000 people in 62 plants across the country.

Ten years changed everything. By 1992, Kellwood employed only 6,500 people in 12 plants nationwide. Southern workers were hardest hit. Kellwood closed factories in Fletcher and Cashiers, North Carolina, in Dresden and Alamo, Tennessee, in Ackerman and Liberty, Mississippi, in Lonoke and Little Rock, Arkansas.

In Asheville, North Carolina, 300 workers lost their jobs. Most had worked at Kellwood for more than 20 years. “It was like a family splitting up,” said Dot Early, a 48-year-old seamstress.

Despite the mass layoffs and plant closings, Kellwood is prospering. In 1992, the company enjoyed annual sales of $900 million, and its chief executive officer, William McKenna, pocketed $2,234,831 in salary, bonuses, and stock options.

How can a company shut down 80 percent of its factories and still post record profits? Simple, says Kellwood in its 1988 annual report. The firm “brought about the closing of marginal and surplus domestic operations, with selected production being moved to low-cost Caribbean plants.”

Translation: Goodbye, Dixie. Hello, Haiti. And Honduras, Guatemala, El Salvador, Costa Rica, and the Dominican Republic. During the past decade, while Kellwood eliminated 9,600 jobs in the United States, it created 8,900 jobs outside the country. Most of the work went to the low-wage, anti-union nations of Central America and the Caribbean Basin, where Kellwood can pay workers as little as 33 cents an hour.

What’s more, Kellwood and other American companies have been exporting jobs with the help of U.S. tax dollars. According to a series of reports by a national coalition of 23 labor unions, the U.S. Agency for International Development (AID) has spent $1.3 billion since 1980 to actively encourage American companies to ship jobs to foreign “free trade” zones. Most of the exported jobs have come from textile, clothing, and shoe factories in the South.

“This jobs export program was started by the Reagan and Bush administrations, but it has continued under President Clinton,” says Charles Kernaghan, executive director of the National Labor Committee Education Fund for Worker and Human Rights in Central America (NLC). “Our government continues to use tax dollars to export jobs and promote misery — at home and overseas.”

New President, Old Policy

The NLC first documented how tax dollars are used to close factories in a 1992 report entitled “Paying to Lose Our Jobs.” Drawing on internal government and company records, the report detailed how AID and the Commerce Department worked to promote offshore production in the impoverished Caribbean Basin region.

For the government, the goal of the “Caribbean Basin Initiative” was to encourage private-sector development in poor nations — to ward off socialism by spreading prosperity through capitalism. For business, the goal was to train cheap, non-union workers to make products for the American market — to ward off their competitors and spread prosperity among themselves.

To develop the initiative, the Commerce Department formed the Caribbean Basin Business Promotion Council, a group of 20 U.S. business representatives who met with top-ranking government officials on a regular basis. Kellwood sat on the Council, along with Sears, Westinghouse, and MacGregor Sportswear. According to a 1988 memo, the Council would “provide incentives for U.S. firms to invest in or import products” from free-trade zones.

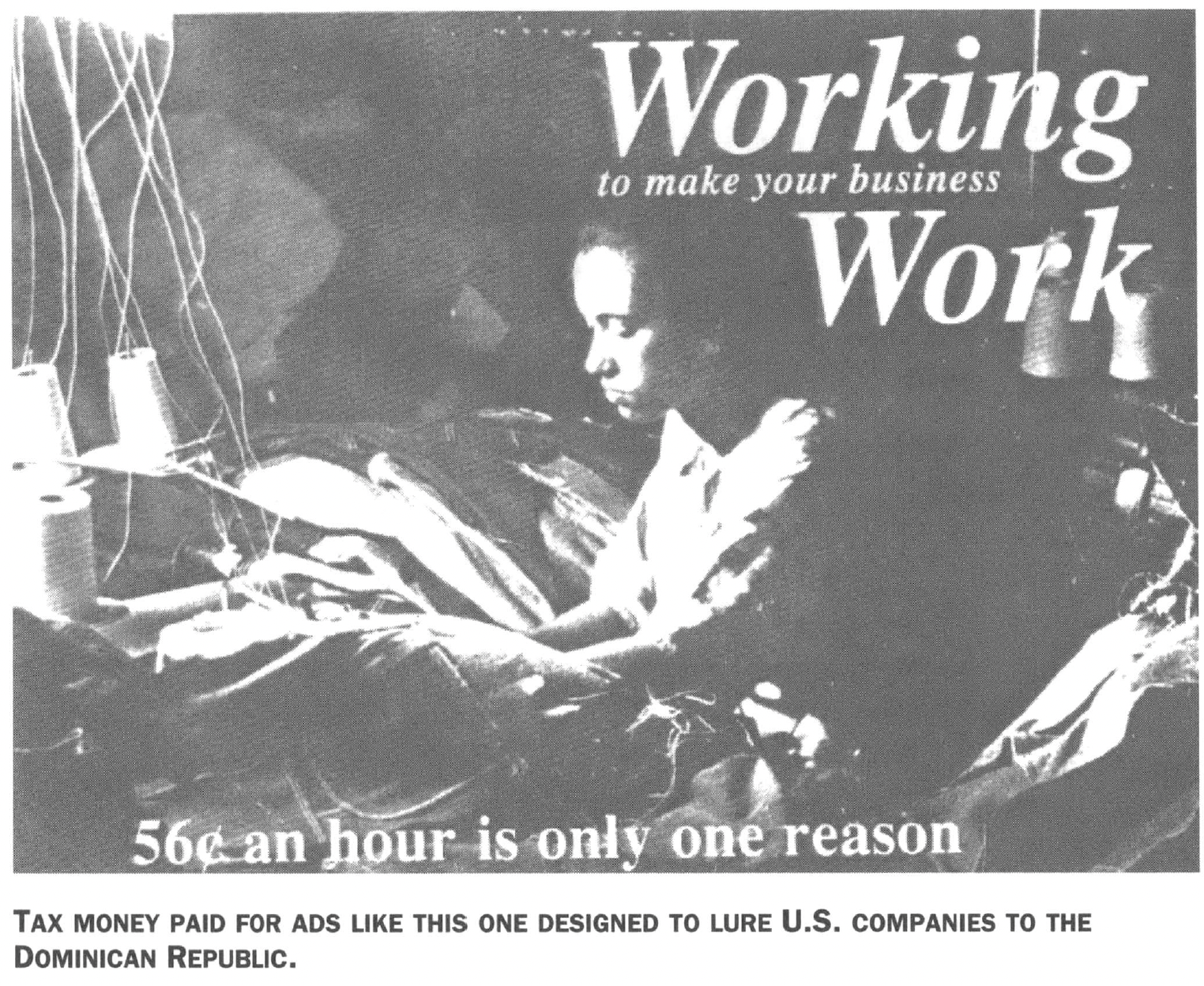

Many of those “incentives” came out of taxpayers’ pockets. Working closely with the Council, the government paid Caribbean countries to set up factories, train workers, and provide technical assistance and low-interest loans to American firms that relocated. The government also spent tax dollars on magazine ads designed to lure U.S. firms offshore. “Rosa Martinez produces apparel for U.S. markets on her sewing machine in El Salvador,” read one 1991 ad in the trade journal Bobbin. “You can hire her for 33 cents an hour.”

That same year, the Commerce Department sent a letter to 1,000 U.S. businesses. “Over the past 10 years, many of your colleagues and competitors have expanded into the Caribbean,” it read. “With labor rates that range from just $1.00 to $3.00 per hour, you can imagine the types of margins which these firms are enjoying. For the reasons cited, you owe it to your company to consider expanding in the Caribbean.”

To confirm that the government was urging American firms to move overseas, the NLC decided to go undercover. Staff members set up a dummy company, went to a Miami trade show, and listened in disbelief as an AID official promised them federal funds and anti-union blacklists if they set up shop in Central America (see sidebar).

Labor Under Cover

The National Labor Committee wanted to investigate first hand what federal officials were offering American businesses to move offshore. Unfortunately, the group only had a staff of three and a bank balance of $200. So they decided to form their own textile firm and go undercover at industry trade shows.

But what should their “company" make? Charles Kernaghan, the executive director, thought they should manufacture handkerchiefs — until Donna Smith, the administrative assistant in the New York office the group shares with the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union, started laughing.

“You look like a bunch of environmentalists,” Smith told Kernaghan and staffers Barbara Briggs and Jack McKay. “Say you make recyclable canvas bags to replace the paper and plastic ones retailers use.”

And so New Age Textiles was born. An ACTWU shop sewed 100 bags for the firm featuring a green logo with the motto, “Save the Trees.” Armed with the samples and some phony business cards, the eager company executives set off for Miami to attend the Bobbin “Apparel Show of the Americas” in April 1992.

Promoters funded by the U.S. Agency for International Development immediately began wooing the young firm on the advantages of moving offshore. “Labor costs are real light” in Jamaica, AID official Stuart Anderson told them. “There are no taxes in the free trade zones” and “we’re not union.”

At the invitation of promoters, they also visited Honduras and El Salvador, where AID officials offered them millions for factory space, worker training, and start-up costs. “We are your tax dollars at work,” laughed one Honduran promoter. Officials also offered them a computerized — and illegal — blacklist to screen out potential union organizers. Feigning concern that moving overseas would idle their “150 employees” in Miami, the execs were advised to lie and say they had declared bankruptcy.

Shedding their briefcases and returning home, Kernaghan and company combined their eyewitness accounts with in-depth research to expose the jobs-export program. “The officials who spoke with us made a big mistake,” he says. “They didn’t know that New Age Textiles had been established by the National Labor Committee, and that we would soon be reporting back to the American public on how our tax dollars are being misused.”

— E.B.

The NLC report was picked up by Nightline and 60 Minutes, both of which independently confirmed the findings. Candidate Bill Clinton immediately used the news to blast George Bush for “actively working to persuade American businesses to move abroad.” Within six days, Congress passed a law prohibiting AID from funding offshore zones that lure American companies.

Once Clinton won the election, however, it was business as usual at the White House. According to a new report by the NLC entitled “Free Trade’s Hidden Secrets,” the Business Promotion Council still exists, and both AID and the Commerce Department want to continue its operation. In fact, federal spending to promote the private sector in the Caribbean Basin has actually increased under Clinton, from $96.4 million in 1992 to $105 million last year.

“This was all supposed to stop in 1992, when Congress forbade AID from funding the export-processing zones,” says Kernaghan. “But the taxpayer money kept flowing during the first year of the new administration. AID found a loophole — they just converted tax money into foreign currencies, and then used it to attract U.S. companies to their export zones.”

Hurting at Home

While the government has teamed up with industry to promote cheap labor overseas, factory work at home has plummeted. Since 1980, the Bureau of Labor Statistics reports, the U.S. has lost three million manufacturing jobs — more than 497,000 in the apparel and textiles industries alone.

The Caribbean Basin, by contrast, has gained 320,000 workers who make apparel for the American market. The U.S. now imports $28.6 billion more in clothing than it exports each year — a three-fold increase in the trade deficit from a decade earlier.

According to the latest NLC report, the flow of jobs to the Dominican Republic has been particularly rapid. The country has been the number-one beneficiary of U.S. investments in the Caribbean Basin, receiving $840 million in American aid since 1982 — almost all of it to create jobs in the private sector.

In 1980, the Dominican Republic had only 16,000 assembly jobs producing for the American market. By last year, the number had soared to 170,000.

The same U.S. companies setting up operations in the Dominican Republic were meanwhile closing plants and ordering mass layoffs at home. Over the past few years, NLC research indicates, companies with production in the Dominican Republic have eliminated 41,571 jobs in the U.S.

A closer look at the numbers shows that clothing workers in the South have suffered the most. All told, 29 companies have eliminated 25,345 jobs in the region — nearly two-thirds of the total. Tennessee heads the job-loss roster with 4,960, followed by Texas, Georgia, Mississippi, and North Carolina.

Kellwood Company led the corporate flight, eliminating 4,766 jobs in the South while creating 7,161 overseas. “We were all really mad,” said Linda Stiffler, who lost her job in 1990 when Kellwood closed its underwear plant in Altus, Oklahoma. “Our work was being shipped abroad to workers who were getting less than a dollar an hour.”

Other big-name clothes manufacturers who have exported Southern jobs include Gerber Products, Haggar, Jordache, Lee, Oshkosh B’Gosh, Sara Lee, and Wrangler. Levi Strauss threw 3,275 people out of work in Arkansas, Texas, and Tennessee while hiring 10,002 in the Caribbean.

In 1992, Maidenform closed its last sewing plant in the continental United States, laying off 115 employees in Princeton, West Virginia. The brassiere manufacturer now has plants in Costa Rica, Honduras, Mexico, Jamaica, and the Dominican Republic.

Patty Davis was one of those who lost her job. “My life insurance was canceled the day I left, and I can’t afford to buy medical insurance,” she told Nightline. “What we’ll do after my unemployment expires, I don’t have any idea.”

While the government has spent nearly $200 million to prop up the apparel industry in the Caribbean over the past two years, it provided only $100 million to retrain American workers like Davis who have lost their jobs. Unfortunately, the program isn’t working very well. Last October, the Labor Department admitted that only one in five retrained workers finds a job that pays at least 80 percent of what their former job paid.

“They say they’re going to retrain workers. But for what?” said Bobby Joe Adkins. A storeowner in Clarksville, Tennessee, Adkins has watched business decline since the Acme Boot Company closed its factory and moved to Puerto Rico, idling 750 workers. “What are you going to retrain a 50- or 60-yearold to do?”

Last May, angry Clarksville workers torched hundreds of Acme boots and launched a nationwide boycott of the Dan Post line to protest the shutdown. “They just want to get away from unions,” said Marshall Tucker. “You won’t see us wearing them boots anymore,” added Kenneth Griffy, whose wife and daughter also lost their jobs.

But Acme knows the industry is heading further south. The company is a subsidiary of Farley Industries, which also owns Fruit of the Loom. Ron Sorini, a senior vice president at Fruit of the Loom, negotiated the apparel and textile provisions of NAFTA, the North American Free Trade Agreement, which is designed to open Mexico to more U.S. jobs and products.

American workers whose jobs move south of the border may not receive adequate retraining, but the NLC discovered that they are sometimes used to train their own replacements. In 1990, Perry Manufacturing opened a factory in El Salvador to make women’s clothing for national chains like J.C. Penney, WalMart, and K-Mart. The following year, the company closed six plants in the U.S., including a sportswear plant in Decaturville, Tennessee that employed 306 people. For six months prior to the shutdown, the company secretly taped workers repairing seconds from the Salvadoran plant — and then used the videos to train employees in El Salvador.

Hurting Overseas

Even companies that brag about their domestic production have moved Southern jobs to the Caribbean Basin. The Dallas-based Haggar Company, which trumpeted its “Made in the USA” labels during the 1980s, began setting up shop overseas in 1983. “Many of our products can be made offshore without hurting our domestic production,” board chair Ed Haggar Sr. assured workers at the time. “They’re a new and growing business for us.”

In the past five years, Haggar has laid off 1,534 Texans. Over the same period, the company has hired 1,561 workers in the Dominican Republic.

Like other proponents of the Caribbean Basin Initiative, Haggar insisted that it had a duty to help poorer nations. “From a moral point, as well as good business, it just makes sense to help developing countries make a living,” Ed Haggar announced. “We cannot sit on this globe, in America, with a population of 230 million, compared with the world population of 4.5 billion, with a great disproportionate share of the world’s wealth, and not help our fellow nations.”

But the influx of U.S. tax dollars and jobs has brought neither prosperity nor democracy to “our fellow nations.” As manufacturing employment in the region has soared, real wages have been slashed by as much as 60 percent. In 1990, the Commerce Department reported that the initiative has made “no dramatic difference yet in living standards in the Caribbean Basin.”

In 1991, the United States International Trade Commission concluded that the initiative “has not fueled economic growth and development in the region.” The study added that “almost all people interviewed stated that it has not lived up to its original billing as a regional economic development program.”

According to Americas Watch and other human rights groups, many Caribbean Basin factories are nothing more than sweatshops. In Honduras, employees at one of the largest apparel factories exporting to the U.S. market have been kicked and beaten for violating plant rules. Women who become pregnant are immediately fired; 15-hour shifts and forced overtime without pay are common.

The Dominican Republic, often held up by AID as its model of development, now exports $1.2 billion in apparel to the United States each year. Yet the country ranks in the bottom 10 worldwide for spending on health care and education. Workers in the “free-trade zones” there have watched real wages plunge by 46 percent since 1980. Hourly pay averages 52 cents.

Companies that move to the Caribbean Basin get more than cheap labor — they get an environment hostile to organized labor. As early as 1984, AID reported that “labor problems in the Dominican Republic industrial free zones are non-existent, primarily because the government prohibits unions in the zones.”

According to the National Labor Committee, Dominican workers who have tried to organize have been immediately fired, their names placed on a blacklist which is circulated openly among companies. “Today,” the NLC reports, “there is still not one single union in any of the free zones in the Dominican Republic.”

The rulers of the Dominican Republic have no worries that the United States will intervene to safeguard worker rights. The vice president of the Dominican Republic has close ties to businessman Alfonso Fanjul, who gave the Bush campaign $100,000 in 1988. Fanjul also owns 160,000 acres of sugar fields in Florida, where he boasts one of the worst labor-rights records in the state.

“Our Futures Are Linked”

Fortunately for workers at home and overseas, the National Labor Committee has forced the Clinton administration to make good on its campaign promises. On January 12, AID issued new guidelines prohibiting the use of any funds — including money already converted to foreign currencies — to finance projects that could result in the loss of U.S. jobs. The guidelines also require AID to cut off funds to any project that violates worker rights.

“It’s a huge policy change,” said Charles Kernaghan, the NLC director. “Every single penny of money that AID spends anywhere in the world is now conditioned on respect for worker rights.”

The new rules come too late to help many textile and apparel workers in the South. “The damage is already done,” Kernaghan said. “The plants are closed up and the unions have been busted.”

Kernaghan also harbors no hopes that AID will voluntarily enforce the new guidelines. “They are virtually impossible to monitor,” he conceded. “You can have all these laws, but the laws don’t mean shit unless you put the pressure on.”

So the labor committee is doing just that. In February, the group prepared a seven-minute video and took out newspaper ads in Honduras to inform workers there of their federally protected right to organize. “The best way to enforce the guidelines is to reach the people,” Kernaghan said. “The people themselves will monitor them.”

In the video, Kernaghan makes an extraordinary appeal to the workers of Honduras. “Let me be very clear,” he says. “The U.S. labor movement is not opposed to foreign aid. We want more aid, not less. . . . What we object to is U.S. companies fleeing the United States, relocating offshore to get their hands on young women forced to work under sweatshop conditions in dead-end jobs for starvation wages. No one gains under a system like this — except the companies and retailers.

“Our goal is that wages in Honduras gradually rise to the level of wages and benefits in the United States,” he concludes. “The opposite would be that the boss pits us against each other in a race to the bottom. We in the U.S. won’t be pitted against our sisters and brothers in Honduras. Rather, our futures are linked, and we’ll struggle together to win our rights.”

Tags

Eric Bates

Eric Bates was managing editor, editor, and investigative editor of Southern Exposure during his tenure at the magazine from 1987-1995. His distinguished career in journalism includes a ten-year tenure as Executive Editor at Rolling Stone and jobs as the Editor-in-Chief at the New Republic; Features Editor at New York Magazine; Executive Editor at Vanity Fair and Investigative Editor at Mother Jones. He has won a Pulitzer Prize and seven National Magazine Awards.