This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

For textile workers, 1993 proved to be a landmark year for organizing in the South. In a wave of elections at a dozen plants from Miami to Nashville, more than 3,500 workers voted to join the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union — the most new members for ACTWU in a decade.

“Momentum is building, ” explains Bruce Raynor, the Southern regional director for the union. “Employees have grown tired of the way companies treat them. Workers are fed up with employers who have no respect for loyalty, provide no job security, and offer skimpy wages and benefits at best.”

Raynor attributes the success to what he calls “a culture of organizing ” at ACTWU. The union prides itself on the diversity of its organizing efforts; everyone from the rank and file to top regional leaders takes an active part in campaigns.

To further increase its diversity, the union has also drawn on a new generation of young activists from the AFL-CIO Organizing Institute in Washington, D. C. The Institute recruits labor organizers from colleges and community groups as well as from the shop floor.

Although Institute graduates helped organize more than half of all new ACTWU members last year, they encountered old-style union-busting tactics throughout the South. Enforcement of labor laws remains weak, and companies facing union elections routinely break the rules —forcing employees to attend “captive audience ” meetings, threatening to close up shop if the union wins, firing workers who support the union.

To understand the tactics faced by textile workers who want to join the union, we asked Lane Windham, an Organizing Institute graduate and a contributor to Southern Exposure, to keep a diary of the organizing struggle at Macclenny Products, Inc. (MPI) in Macclenny, Florida. Workers there voted to join ACTWU in December — but as this diary of an organizer shows, the majority doesn’t always rule. (The names of some workers have been changed to protect their identities.)

November 29

They put an American flag in front of the plant today.

This flag fascinates me. In the nine weeks since I’ve been here, MPI has done all they can to prevent their employees from unionizing. They’ve led workers to believe the plant will close if the union gets in. They’ve fired union supporters. On the company list of eligible voters that I received today, they’ve included plant supervisors, technicians — even the boss’s secretary. We’ll have to go to court to prove that all this violates the National Labor Relations Act.

This doesn’t look like liberty and justice for all from where I stand. MPI is owned by Target, a low-price suit manufacturer which moved part of its cutting operation south to Macclenny in 1987. The people who work for MPI want to join Target employees in Pennsylvania who have been represented by ACTWU for 30 years. Macclenny is midway between Jacksonville and the Okefenokee Swamp. MPI is the largest employer in town.

Workers at MPI cut the parts for suits which are then sewn together in the Dominican Republic and returned to Macclenny for shipping. MPI is one of thousands of “807” cutting operations, named after Section 807 of a U.S. tariff law which permits companies to evade duties on foreign-made products if some part of the manufacturing is first done in the States.

The people at MPI who cut, label, count, and spread suit after suit each day didn’t know much about “807” before they called the union. They did know that they were tired of getting disciplinary “points” if they left work to care for a sick child or go to the doctor. (One woman even got points for having a heart attack in the plant.) They knew that $5 an hour doesn’t pay the bills. And they knew that somewhere in Pennsylvania, people who did the same work had a union — and a contract that paid $2 an hour more.

The workers at MPI knew about Pennsylvania from an earlier organizing attempt at Macclenny in 1988. Almost all of the 125 employees knew about that union drive, even though only 15 of them were here at the time. History like this is kept alive, whispered on break and in the bathroom.

November 30

It’s Tuesday. That’s meeting day.

We have our meetings in an oversized Day’s Inn room. We remove the beds and pilfer chairs from all over the motel. Twenty to 30 people usually attend meetings, so it’s a tight squeeze.

For the past few weeks, the workers have been telling Monica Russo, Chris Hines, and me — the ACTWU organizers — that the company has convinced many of their co-workers that if the union comes in, the plant will close.

We made this the theme of today’s meeting. We explained that ACTWU has won 11 elections in the Southeast so far this year, and not one of those places has closed. We told people how much their company is profiting. We armed them with facts.

For the most part, the 25 people who attended today’s meeting already have their minds made up. They’re the diehard union supporters who will educate the people who work next to them about the union. We make up leaflets for them to hand out, but the most effective tool by far is word of mouth.

This committee of union supporters is the core of the organizing campaign. Many have put their lives and families on hold in order to win the union.

Today they are buzzing about their first union newsletter. Many had written articles, and they took a lot of abuse from anti-union co-workers about their personal statements. They gain strength by being packed in a room together. They’re ready for Monica’s rousing speech about exactly how much money they are making for the company. After being made to feel like hoodlums all day, they’re ready to hear that they have a right to stand up for themselves. They’re ready to hear that they can win.

Eight weeks ago, they had an excellent chance of winning. Now, with the help of Jackson and Lewis, one of the country’s most notorious union-busting law firms, the company has turned the campaign into a neck-and-neck battle.

Jackson and Lewis teaches companies like MPI how to defeat pro-union workers. They hold seminars with supervisors and tell them their job is to stop the union. “Weed ’em out,” a J&L consultant once told a group of employers. “Get rid of anyone who’s not going to be a team player. I’d like to have a dollar for every time there’s union organizing and the employer says, ‘I should have gotten rid of that bastard three months ago.’”

After the union drive started, MPI completely revised the employee handbook, wiping out everyone’s dreaded absentee “points.” Since then, the company has worked to get workers thinking about everything but why they called the union in the first place.

December 1

I visited Mandy Taylor tonight.

Mandy has only been working at MPI for less than a month. When she was hired, she seemed like a solid yes vote. Her husband works at the railroad, which is union.

But when I stopped by Mandy’s trailer this evening with Sharen McDuffie, the sole voice of the union on the shipping side, we weren’t exactly greeted by a cheerleading squad.

Mandy was convinced that if the union came in, people could no longer get their raises and vacations. She told us that we would all have to go on strike. Of course, she let us in on the big secret that the plant would close if the union came in.

Sharen took it from there, puffing on one of her long cigarillos. “That manager with the perfect hair has been talking to you, hasn’t he?” she demanded. “Did he tell you that 99 percent of the time there isn’t a strike, and that we would have to vote to strike.” Sharen also explained that a legally binding union contract is the only way to make changes for good at MPI.

Mandy wasn’t convinced. Her only other job had been as a check-out clerk at Wal-Mart. The only benefit that job offered was 25-cent Cokes in the employee break room. Wal-Mart paid minimum wage, whereas Mandy makes $5 an hour at MPI.

Finally, Mandy confided to us, “You know, I’ve just never been one to show myself. In school, I was always the good girl. I just don’t think I’ll tell anyone how I’m going to vote.”

She was telling us she was voting no. She knew what the union could do for her. Yet for Mandy, admitting that the man in the suit was flat-out lying about the risk of unionization felt like defying her fourth-grade teacher.

It was easier to stay quiet — especially when the company had convinced her that losing her very first battle against authority would mean returning to Wal-Mart.

December 2

UPS messed up and delivered our union stickers to the plant’s front office yesterday! That gave the company a free shot, but we got the stickers back. UPS is union.

I took a stack of the stickers over to the McDonald’s where everyone meets for lunch. I only caught two people, but when the workers showed up this afternoon, they were covered from head to toe. That told me that the union network was active inside the plant.

Delores put stickers on her white sneakers. One foot read “RESPECT,” and the other read “UNION YES!” Geneva had a “NO MORE POINTS” sticker plastered on her very pregnant belly.

The latest company leaflet featured a reproduction of a Florida unemployment form. It read, “This is filled out by people who lose their jobs.” It ended with, “At Macclenny, our employees are working. Compared to many in the apparel industry, we are very fortunate.”

“Fortunate!!” scowled Delores. “They haven’t seen my paycheck.”

She took the “$$$” sticker for her feet tomorrow.

December 3

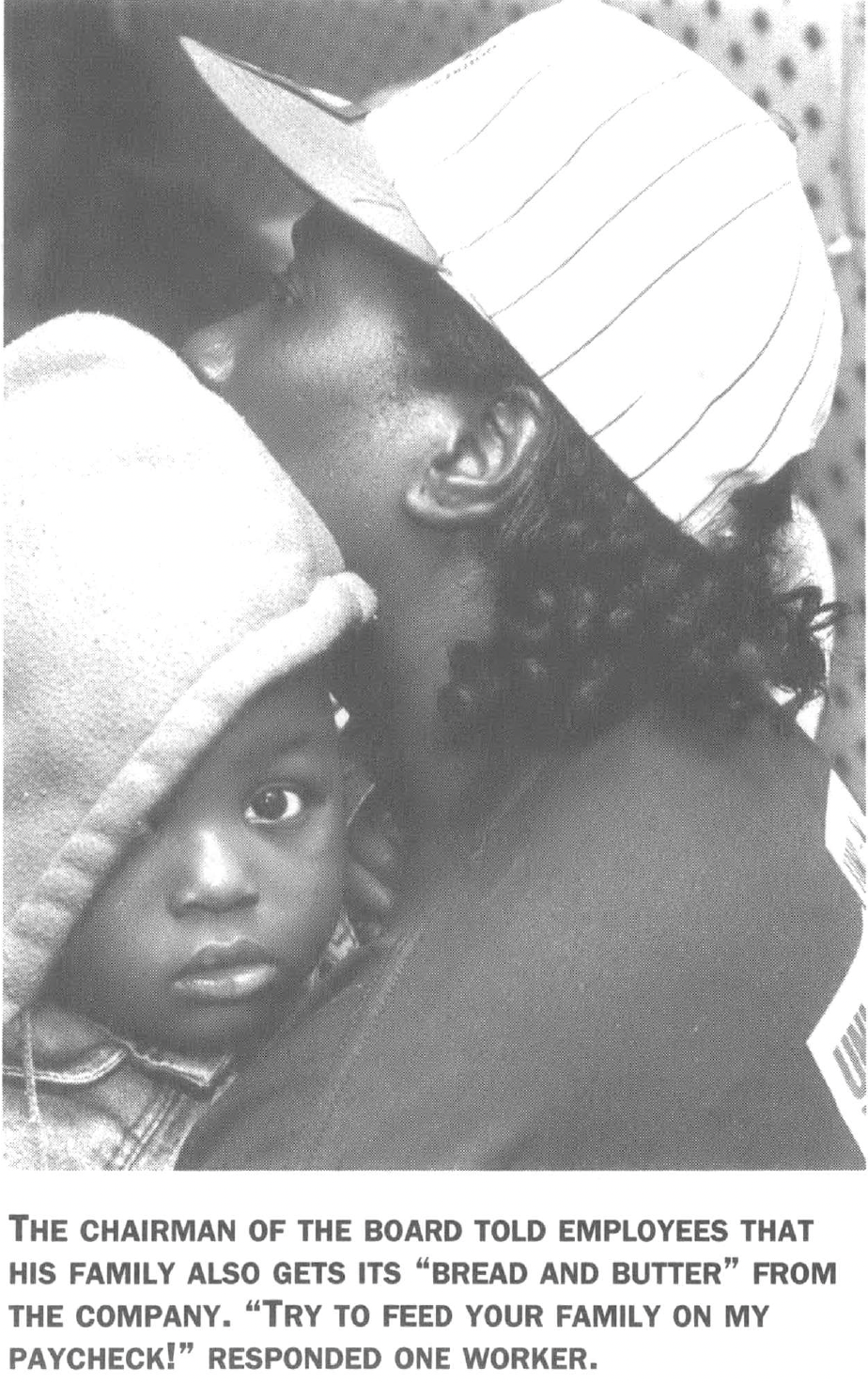

Workers were ordered to attend another anti-union meeting today, and they told me later that the chair of Target’s board of directors made his intentions very clear. “There is no magic. This isn’t a fairy tale. We’re talking about reality. We don’t want a union here.”

Workers who attended said he went on to tell them that Target signs their paycheck, and they should be grateful to have a job.

Christy Wilkerson called out, “If you weren’t making no money, y’all wouldn’t be here. Y’all ain’t bankrupt.”

“English is my native tongue,” the board chair snapped. “Please use it with precision.”

Christy said he refused to answer any questions regarding the reasons the workers want a union. He wanted them to forget about absentee points and low wages. Instead, he told them to ask themselves, “What benefits do I currently have that could be thrown on the table? What could my family and I afford to lose?”

He told them that the company’s profit was none of their business. He showed slide after slide of newspaper articles about strikes and plant closings. He highlighted places where the union had lost campaigns. He ended with, “My family and I get our bread and butter from Target, too, you know.”

When Christy called out, “Try to feed your family on my paycheck!” he ordered her to be quiet or leave the room.

“Remember,” he added, “the company makes all hiring and firing decisions. The union has no say in that.”

Delores looked at him as workers filed out of the room. “If the union can’t do anything for us,” she asked, “then why are you fighting it so hard?”

I don’t know of a group of people who deserve a union more.

December 4

I met Wendy Hodges at the beginning of the campaign — even before the first union card was signed. I was visiting her best friend, Sarah Caldwell. One of my contacts thought Sarah could be a potential union leader. The same contact thought Wendy would be too afraid to fight.

When Wendy walked in unannounced and found out I was from the union, she looked at me with a combination of shock and terror. It was as though she saw Fidel Castro himself sitting in her friend’s Lazy Boy recliner.

I thought to myself, “This one’s gonna be the one that runs back to tell the boss the union is in town.” Sarah continued discussing the union with me with an easy calm. She both agreed with everything I said and defended the company in the same breath. Always a very bad sign.

Wendy, meanwhile, was willing to argue with me, although she didn’t trust me. Her first words were the inevitable, “I need my job, you know.” Then she questioned me about what the union could do for her. That’s perhaps the best sign.

Since then, Wendy has attended every union meeting. She stood and smoked by the door for the first meeting, but now usually sits on the front row.

Last week, a supervisor asked her, “Have you ever eaten green beans out of your garden for breakfast? You will if the union gets in.” She told him she was once so poor that she’d eaten someone else’s green beans for breakfast.

She’s fighting, and she’s hungry to win.

That’s why my heart jumped when she walked in this morning and wouldn’t sit down. She told me she had some questions, and then told the kids to wait in the car.

She told me the chair of Target’s board had cornered her after the captive-audience meeting yesterday. “He made it sound like he was looking out for me. You know, I don’t believe him. But he told me how the union caused a plant to out-and-out close in Pennsylvania. He made it sound like those people didn’t really vote to strike.”

She had been staring nervously at a spot on the wall, but now she looked at me. “I don’t know who to trust any more. How can I be sure?”

I tried to point out some of the things her boss didn’t mention. He didn’t discuss her recent pay cut. He didn’t bring up the time her supervisor told her to beg harder for overtime. He didn’t tell her Target had moved the union shop in Pennsylvania to the Dominican Republic so it could pay workers $10 a day.

I spoke evenly, but I was as nervous as Wendy. “My God,” I thought, “this woman is stronger than the rest because she’s had to come so far. How will the others react?”

So when Monica, another organizer, finally got Wendy to sit down and put things in perspective, she calmed more than one person in that room. When Wendy left, she took union stickers for the kids in the car.

Tonight, I am very, very tired.

December 5

When the ACTWU members from Levi-Strauss in nearby Valdosta came to one of our union meetings in Macclenny, they refused to stay very long. “You don’t want to be caught here after dark,” they told me. “Not if you’re black.”

While some of the violent white backlash against the civil rights movement has reached Macclenny, there is little evidence of the movement’s victories. None of the clerks at the Winn Dixie nor waitresses at the local restaurants is black. All the town officials I saw showcased in the local Christmas parade were white. So were all the parade’s various beauty queens. Twenty of MPI’s 125 employees are black. There are no blacks in management.

So I can’t say that I blame Tina Jacobs, an African-American woman, for turning me down when I first urged her to sign a card. Her look said, “So, what can this little white girl tell me that I don’t already know?”

But she didn’t get away that easy. When I went back to visit Tina today, I went with Archie Mae Richardson, one of several African-American women who have supported the union from the beginning.

There was a telling contrast between this housecall and the one with Mandy, who is white. Mandy didn’t want to believe that the company was lying to her. She wanted to trust the company, because she wanted to believe that the company values her work.

Tina is far past wrestling with whether or not to trust the company.

She reminded us that she had been with the company for several years — far longer than most black workers manage to stick around. She told us about how younger white women were called back from a layoff before she was. She’s scared that if the union loses and she has supported it publicly, her supervisors will give her twice as hard a time. In their eyes, she’ll not only be black, but union black.

She was for the union all along, she told Archie. She just didn’t want the company to find out. She signed a card before we left and promised to attend next week’s meeting.

December 6

I went to the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) office today in Jacksonville. They’re the people who are supposed to safeguard the democracy of this whole process.

The Jacksonville office is more welcoming than other Board offices I’ve visited. Here, you don’t have to walk through a metal detector when you enter the building.

I’m filing charges on behalf of one of the workers the company fired just before Thanksgiving. A week before he was fired, Arnold Clayton wore a sign that read, “Stop slavery at Macclenny Products. Vote Yes December 10th.” When his supervisor made him take the sign off, he stuck it on the wall. MPI claims they fired him for “refusal to follow company policy.”

Even if we win Arnold’s case, it will be at least a year before he sees a paycheck. MPI fired a woman during the 1988 campaign, and it took months of litigation to win back her job and thousands of dollars in back pay.

In the midst of heated campaigns, companies often consider the prospect of such legal bills a small price to pay to keep the union out.

I’m also filing charges against the company for saying that the plant will close and for making other illegal threats. Many of the supervisors haven’t even been attempting to cover their tracks. MPI knows they won’t have to pay any fines if we prove they’ve broken the law. The big, bad punishment for their offenses will be to post a sign that essentially says, “We’ve broken the law.”

That’s it. They have to hang a blue-and-white sign.

Perhaps we could just persuade them to put Arnold’s sign back up on the wall.

December 7

Only seven of the workers at MPI have any previous union experience. Most have never seen a union in action. We’ve had to really work to give them a vision of just how different MPI could be with a union.

“Yes, it can happen,” Becky Hess urged, “but only if you make it happen, like we have.” Becky used to work at Target in Pennsylvania, and now she’s an ACTWU organizer. She came to Macclenny today with Lea Patterson, a current Target worker. They told us that the union shops in Pennsylvania do the same work as Macclenny, but for a couple bucks an hour more, and with a lot less grief.

For many people at the meeting, it was a convincing glimpse into the Promised Land.

First, Becky ripped the scary Halloween masks off Target management. She talked about the chair of the board who shouted down the workers last week. “He brings me coffee during contract negotiations,” she smiled. “With sugar.” She described the wage increases and elevated benefits Pennsylvania workers have won. “Pennsylvania doesn’t have absentee points,” she reminded them, “and we’ve got the power to keep points out.”

She described how Target tried to make sure that Macclenny workers wouldn’t know what they are missing. They’d even warned the Pennsylvania truck drivers not to talk about the union when they delivered goods to Macclenny.

Becky emphasized that the workers in Macclenny must make their union their own. “You’re going to still be fighting Target when you’ve got that contract in your hand. You’ll just be fighting on equal ground for the first time.”

The message she gave workers to carry back to the shop floor tomorrow is simple in its power — “Target can be beaten. We’re proof. You have a right to win.”

My heart soared as the meeting ended. After all, we’d already beaten Target’s efforts to keep workers apart. Over 40 people attended the meeting. That’s the most yet.

We’re gonna win. We’ve just got to. What more could it take?

December 8

When Christy Wilkerson came to my hotel room sobbing this morning, my first thought was, “My God, they’ve fired her, too.”

For many workers, the union and Christy are one and the same. If the company was going to pick a scapegoat two days before the election, she could very well have been it.

But they hadn’t gone that far, probably fearing a backlash. Instead, Christy said, they cut her hourly pay by a dollar. It was a dollar that would reach deep into her pocketbook. She already receives food stamps, even though she works 40 hours a week.

But losing that dollar also slices into her pride. Christy is known for not taking anything off anyone. Her father is a labor leader with the Communications Workers of America, and she’s “daddy’s girl.” Now she will have to walk into the plant, day after day, and accept doing the same work for less money. If they’d fired her, at least she could claim the moral high ground. Now, if she quit over the money, she couldn’t even collect unemployment.

We’re filing charges for her. She didn’t stop crying when I told her that, though.

A couple hours after Christy left, Brenda called from the break room phone. They needed 13 more union T-shirts. She had the names ready. We’d already given out about 40 yesterday.

She told me the cutting floor looked like a union rally because so many people wore T-shirt and hats. Supervisors were going around with notepads, writing down the names of people wearing shirts, but their scare tactic wasn’t working.

The shirts read, “Proud to be American, Proud to be Union,” and featured a huge American flag. Run that up the pole, MPI.

December 9

Rumors had been circulating for weeks that the president of the corporation would visit Macclenny the day before the vote. Bob Bayer made his heralded appearance today, right on schedule.

Every employee was ordered to attend the meeting. Some of them told me later that he all but said the plant would close if they voted for the union. “We need the flexibility to compete — that’s why we set up Macclenny as a non-union facility. If that flexibility ceases to exist, Macclenny will cease to exist. Period. That’s all there is to it. I fear that ACTWU would put the economic reasons for our existence into jeopardy.”

Bernice Crawford, a label sewer, put it best — “You’d have to be a crazy person not to read between the lines.”

Then Bayer told them he had fired the plant manager. That’s the guy everyone hated and who was a chief impetus for the union organizing drive.

Target was scared, and they were taking no prisoners.

December 10

We went into the pre-election conference at 12:30. That’s when the company and union representatives meet with the Labor Board agent to discuss the list of eligible voters and other election arrangements.

The meeting was in the break room, and it gave me and my fellow organizers our first opportunity to enter the plant. The break room is actually a platform that overlooks the floor, and we could see everyone as they worked. Union T-shirts were all over the place. Many workers waved at us, proud that their union reps were in their plant and that the company had to take it.

After the conference, some of the spreaders told us the company had given them a huge bonus an hour before they voted. The company had been promising them a pay raise for weeks, but they hadn’t seen it yet. Until voting day. One worker said he would vote no now that the company had come through with the money.

All we could do was wait.

As we sat in the union office, I flipped through the leaflet we put out today. Fifty of the people voting today had put their individual pictures on this leaflet with a quote about why they wanted a union. Fifty people were willing to step that far out, even though they could have voted secretly.

I waited with Vernon Davis, a union supporter who had actually adjourned one of the company’s captive-audience meetings before the Boss had finished. Everyone just followed him out the door. That was before Thanksgiving, though, before Vernon’s operation. He’d taken a medical leave in order to donate one of his kidneys to his father.

Today, he rolled into the plant in a wheelchair to vote.

Robin Bryan didn’t make it that far. Robin didn’t work today or yesterday because her mother just had a heart attack. Everyone knows Robin supports the union — earlier in the campaign she ripped an anti-union poster off the wall and paraded through the plant with it. There was no question how she would vote today.

But when she went in to vote, the company observer told her she no longer worked there. “They fired me while I had my ballot in my hand,” she told me.

They claimed they fired her for points. She’d gone over her “allotment” when her mother had a heart attack yesterday. She’d gotten many of her other points caring for her son, who she feared may have diabetes. She’s a single mother.

I knew the freelance photographer had arrived to shoot the union victory when I saw the bumper sticker on the old Toyota: “Visualize World Peace.” There just aren’t too many of those in Macclenny.

“So, what is this? Some kind of election?” she asked me as she loaded her Nikon.

“Yeah, it’s a union election,” I answered. “They’re voting right now. Let me explain all this to you so you’ll know what to do.”

“Well, I did photograph the Clinton victory party, you know.” She peered at me through the lens and asked, “So, what do you have to do to get a union anyway? Just vote?”

Not quite.

We went into the vote count at 3:30. There were 124 people on the company list of eligible voters. We challenged nine of the ballots, saying they were cast by supervisors, technicians, and other workers who were ineligible to vote under federal law. The company contested three — Arnold and Robin, whom the company had fired, and another employee receiving workers compensation. The 12 “challenged” ballots were sealed in envelopes. They would be counted only if they would determine the outcome of the election — that is, if neither the company nor the union got 63 votes.

The Labor Board agent broke open the box and stirred up the ballots. He told the observers to watch as he counted the votes. The first vote was a yes. So was the second. The third was a no.

When there were no more slips of paper left to count, he turned the box upside down for us to see. The union had 58 votes. The company had 56.

A majority of workers voted to join the union — but they were robbed of their victory. Now we have to go to court to have the nine ballots we challenged thrown out.

The whole process will take years. Years that workers will spend playing by the rules of the democratic process, while the company continues to make its own rules — and break them as it pleases.

Wendy Hodges stopped by after our “victory” party. People were upbeat, and their determination to win in court lifted my spirits.

She left the kids in the car again, but this time she didn’t stay long. We joked about how we’d met at Sarah Caldwell’s house, and Sarah turned out to be the one counting the votes for the company.

“I don’t really understand about the court, and all,” she told us. “I don’t know if we won or not. I just wanted to tell y’all that I won. Me. I won.”

Maybe Wendy did win. But she deserves a union.

Tags

Lane Windham

Lane Windham is Associate Director of Georgetown University’s Kalmanovitz Initiative for Labor and the Working Poor and co-director of WILL Empower (Women Innovating Labor Leadership). She is author of Knocking on Labor’s Door: Union Organizing in the 1970s and the Roots of a New Economic Divide (UNC Press, 2017), winner of the 2018 David Montgomery Award. Windham spent nearly twenty years working in the union movement, including as a union organizer. She earned an M.A. and Ph.D. in U.S. history from the University of Maryland and a B.A. from Duke University.