The Burn Belt

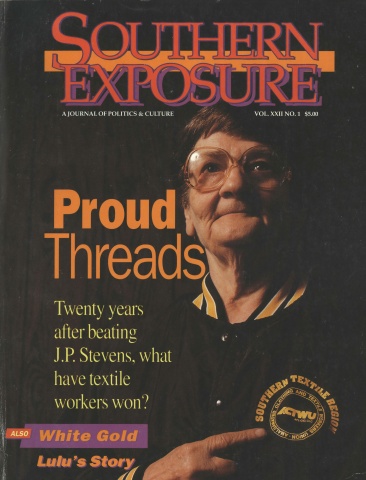

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

The blaze that charred Atlanta in Gone with the Wind was more than an isolated display of Hollywood pyrotechnics. From the first European settlements to the latest Southern factories, high rates of fires and fatalities have earned the region a dubious reputation as the “burn belt.”

One of the nation’s earliest recorded fires destroyed most of the Jamestown settlement in Virginia in 1608. “Most of our apparel, lodging and private provision were destroyed,” Captain John Smith wrote. A New Orleans fire in 1788 left 816 of the city’s buildings in ashes, and a second fire in 1794 destroyed much of what had been rebuilt after the first blaze.

Some of the South’s most historic cities have been leveled by wartime fires. General William Sherman ordered his troops to torch Atlanta and Savannah during the Civil War. One eye witness described the burning of Atlanta as “a grand and awful spectacle. The heaven is one expanse of lurid fire.” Confederate troops set Charleston and Richmond aflame to prevent the Union from seizing the cities’ supplies.

In this century, industrialization has increased the risk of fire and explosion in working-class communities. In 1947, 400 people died when a cargo of ammonium nitrate fertilizer exploded at the Monsanto Chemical dock in Texas City. In 1989, a blast and fire at Phillips Petroleum killed 23 workers and injured 232 in Pasadena, Texas. In 1991, a grease fire at the Imperial Foods chicken processing plant in Hamlet, North Carolina killed 25 workers and injured 54 others trapped behind locked exits.

The most striking fire pattern in the nation, according to the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA), is the high fire death rate in the South. Between 1988 and 1992, Southerners were 25 percent more likely to be killed by fire than those outside the region. The South also has a higher rate of fires and more property damage from blazes than other regions.

Lightning and other natural causes are to blame for some fires. Mark Lackey, a meteorologist with the National Climatic Data Center, says lightning is most common in the South, particularly in North Carolina and along the Gulf Coast of Florida.

But most fires are caused by social and economic conditions. “High fire rates are directly related to poverty,” says Sharon Gamache, executive director of the Learn Not to Burn Foundation, an affiliate of the NFPA. Poor people have fewer opportunities to learn about fire safety and less money to spend protecting their families. “If you’re on a limited income, the cost of a smoke detector may be prohibitive,” observes Meri-K Appy of the NFPA.

In addition, many fire deaths in the South result from lax fire codes and weak enforcement. In 1989, 32 elderly residents died in fires at Virginia and Tennessee retirement homes that lacked basic sprinkler systems. Industry representatives have resisted legislation mandating sprinklers because of the cost.

Ernest Grant says many of the fire injuries he sees as a burn nurse in Chapel Hill, North Carolina are caused by poverty and lax housing codes. Many poor people who have no heat put kerosene heaters dangerously close to their beds, he says, and manufacturers often use flammable materials to build mobile homes.

But most fire injuries Grant treats are caused by a staple of Southern agriculture and one of the nation’s leading killers: tobacco. “In well over 50 percent of the injuries we see, smoking plays a part. Sometimes people just fall asleep smoking in bed.”

Better fire codes coupled with education are reducing fires in the South. The NFPA provides a curriculum to teach fire safety in public schools, and the Learn Not to Burn Foundation funds fire-prevention programs in high-risk communities. In Mississippi, a state with one of the worst fire death rates, the Foundation supports a local coalition that is developing a fire-prevention education program for pre-schoolers.

Louisville, Kentucky had the fifth worst fire death rate in the nation before Russell Sanders took over as fire chief in 1986. Sanders gradually shifted the fire department’s emphasis from fighting fires to preventing them. Firefighters now visit schools and nursing homes to teach fire safety, go door-to-door inspecting homes and installing free smoke alarms, and organize fire-prevention festivals. This year they plan to train social workers to teach the elderly how to protect themselves from fire.

Such education has reduced the need for fire runs, Sanders says. “Since we implemented the program, fires are down 19 percent and we have seen a 35-percent reduction of fire deaths. We have not lost a single child in four years.”

Sanders says implementing good fire-prevention programs in communities nationwide would dramatically reduce death and damage from fires. “I’ve seen well over a 1,000 fires in 27 years,” he says, “and I’ve never seen one that could not and should not have been prevented.”

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)