This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 22 No. 1, "Proud Threads." Find more from that issue here.

Sandy is a proud woman. For the last 14 years, she has been a top production worker at a furniture factory. She takes good care of her family and participates in her children’s school activities. She dreams that one day she and her husband will be able to buy a new home and send their two children off to college. Like many adults, Sandy can’t read and write very well — and like many adults with low literacy abilities, she functions well as a contributing member of her community.

You don’t see people like Sandy when the mainstream media portray adults with low literacy abilities. Instead, adults who cannot read and write are shown as confused, in crisis, lost souls, or carriers of some disease. Negative stereotypes have far-reaching implications for how literacy problems are defined, and how literacy services are provided. They also affect how adults with literacy problems see themselves.

Literacy is a serious problem in this country; the Census Bureau estimates that seven million Southerners never got beyond the ninth grade. Print and electronic media provide powerful vehicles to draw attention to the problem. Unfortunately, too often they are used to “blame the victim,” portraying adults with literacy problems as responsible for creating their own situations. This places the spotlight on the people who have the problem, and shifts it away from the schools, politicians, businesses, religious institutions, and other organizations which share responsibility for creating and addressing social issues such as literacy.

Sandy’s baby daughter is five years old and has started kindergarten. Sandy would like to be more involved in her daughter’s schooling, so she begins thinking about working on her own literacy skills. She’s seriously considering attending a class somewhere in her community.

Driving home from work, she hears about a program on the radio. The announcement says that people who don’t read well should get help because “illiteracy is a disease that passes from one generation to the next. ” Sandy feels scared and ashamed.

Most media ads about literacy campaigns are directed to people for whom literacy is not an issue — people who read and write well. One ad features a picture of The Holy Bible with the caption, “For someone who can’t read, this is pure hell.” The ad urges potential volunteers to call a local literacy program to “tutor a lost soul.” Another print ad depicts a can of Starkist tuna next to a can of Amor’e cat food, suggesting that those who cannot read might mistakenly buy cat food instead of tuna to feed their families. Again the ad targets literate people, encouraging them to volunteer their time or to urge someone with a reading problem to get help.

The creators of such ads insist that powerful images are necessary to get the audience’s attention. An image of a mother and her child with empty holes where their faces should be does get our attention — but it also suggests that literacy problems are hereditary, and that people who cannot read and write well have “nothing” in their heads. Crafty and sensationalized ads may catch the eye of potential volunteers, but what message do they send to those who might benefit from their services?

Negative stereotyping sometimes makes adults feel unwilling to ask for help; they feel ashamed and worried that they will be judged negatively if they let people know about their literacy problems. Such advertising distances adults with well-developed literacy abilities from those with literacy problems — both in terms of human qualities as well as literacy abilities. Few, if any, media ads acknowledge the incredible wealth of knowledge and experience possessed by people with low literacy skills, or give respect to their strengths and successes.

Who benefits from suggesting that people who cannot read are lost souls, or that they might abuse their families by feeding them cat food? Such images may help service providers recruit a few new volunteers or get a little new funding in the short run, but promoting negative stereotypes ultimately contributes to the problem rather than the solution. Volunteers or teachers who are attracted by such advertising are likely to promote prevailing stereotypes, making it difficult for students to develop a sense of their own power and control.

My Uncle Samuel

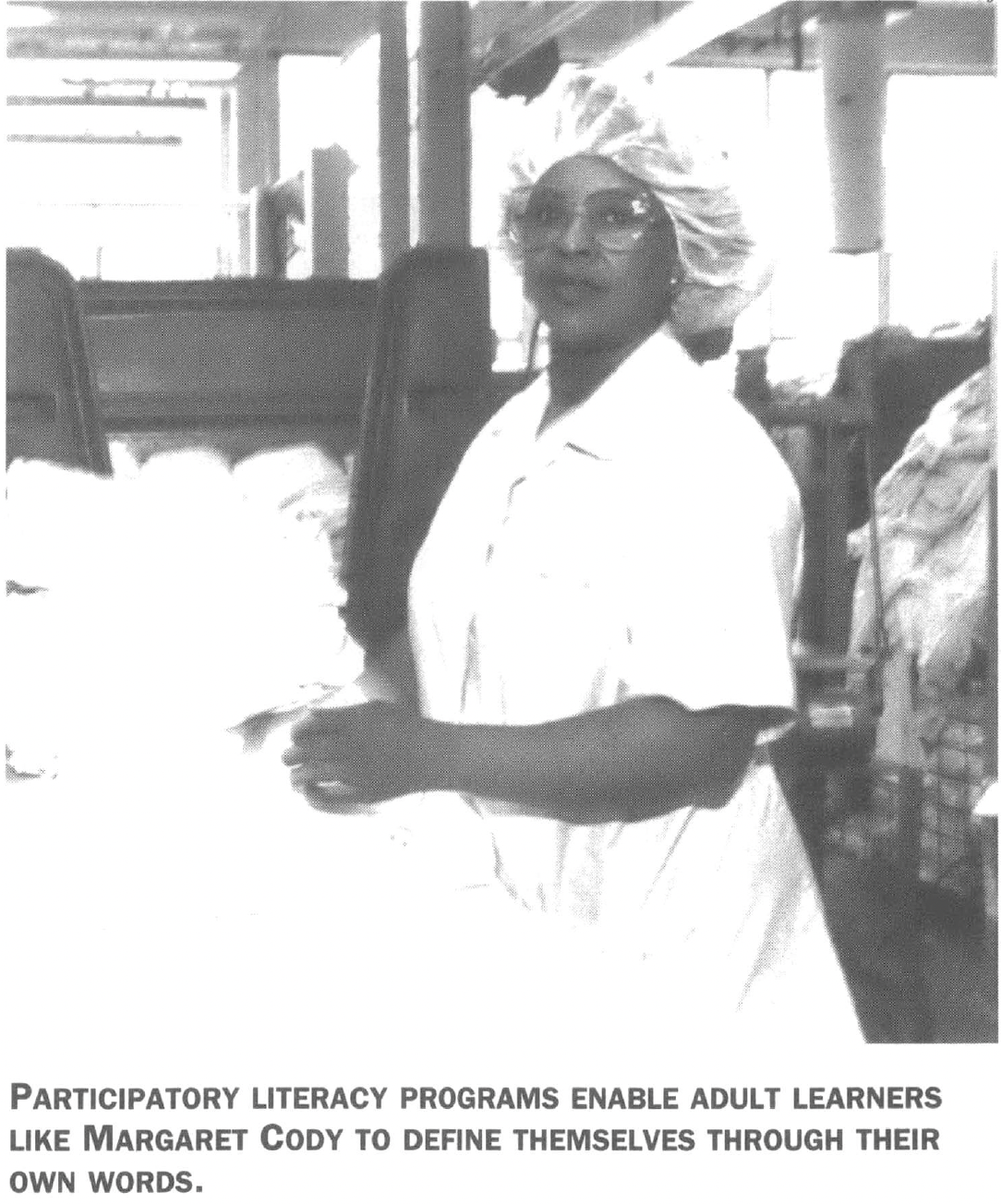

Margaret Cody worked on her literacy skills in a program for employees at Duke University in Durham, North Carolina. “I was a professional dancer for 15 years for the James E. Strait show, ” writes Cody. “I love to write music and poetry. I also love my classes. For my age, it’s a great educational experience which keeps me up-to-date. ”

My uncle Samuel is a funny man

He likes to tell jokes

and make funny faces

When I was small

he used to tap dance for me

and I would tap dance with him

Boy, he could tap

I remember

whenever I wanted to go

to a movie

My uncle would give me show fare

and tell me to have a good time

He would make sure

I had money for hot dogs

and pop corn

But now he is getting old

and sick

He can’t do the things he used to do

But he still tries

He used to be one dressing man

He still dresses real cool

but not like before

I wish those days were still here

But time goes on

To effectively address problems of adult literacy, we must engage in a critical analysis of the messages portrayed by the media. We must carefully examine ads and ask, “Whose interests are served by this particular image?”

Literacy programs should also take a pro-active position by providing positive and alternative perspectives for ad agencies, reporters, radio announcers, and others in the media. Too often we are dependent on the goodwill and creativity of ad agencies and newspaper editors who have little perspective on literacy issues. Literacy educators can provide leadership in promoting positive images of adults with literacy problems.

To understand the complexity and impact of stereotyping, literacy educators must also examine their own perceptions of adult learners. If educators buy into general media notions of adult learners as lost souls, they are unlikely to encourage student involvement in decision-making. Instead, they are likely to feel that learners are incapable of making decisions about curriculum and assessment, even though participatory learning offers an effective and important approach to literacy education.

Participatory literacy settings — where students help shape curriculum, program focus, structure, and their own assessment — provide environments that allow all involved to move beyond stereotypical notions of adult learners. Programs like the Star Adult Education Center in Biloxi, Mississippi and New Horizons in Franklin, Virginia enable adults to define who they are for themselves. By centering lessons around the lives, cultures, and backgrounds of learners, teachers can build on their strengths and achievements. Lessons can be designed to help students cope with negative images and place learning experiences in a broader perspective.

Such programs give students the opportunity to define themselves through their own voices, telling their own stories and writing about their own lives. Through the process of student writing, learners share their experiences and feelings about situations related to literacy and how they cope with family, work, and community life. The writings help dispel myths about adult learners and serve as reading material for other students.

As a result, teachers don’t have to figure out how to talk about students; students talk for themselves. Students and teachers respect each other as contributing members of their shared community. And students share with each other their struggle for improved literacy with dignity.

Sandy was talking with Nora, one of her coworkers, during lunch, explaining how she wanted to learn to read and write better but didn’t know exactly how to go about getting help. Nora looked surprised and said she had been thinking about the same thing but didn’t really want anyone to know she had problems with reading. She explained that she was ashamed; she didn’t want people to think that she was stupid.

Sandy told her friend she understood what she meant. She said she had heard about a local literacy program and suggested that they try it out together. They agreed that it would be better if they went together, because they both understood what it was really like.

Tags

Jereann King

Jereann King is director of programs for Literacy South in Durham, North Carolina. (1994)