This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

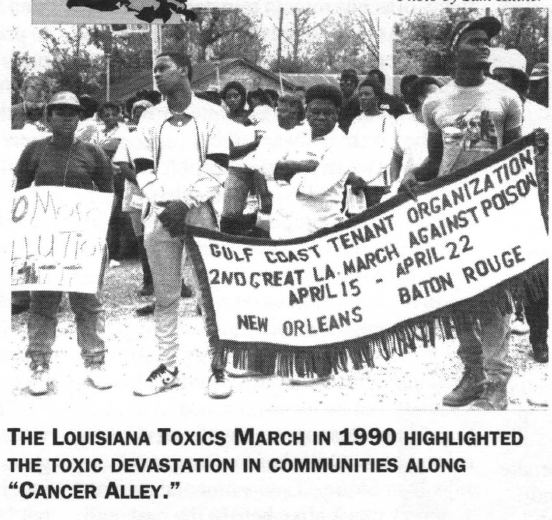

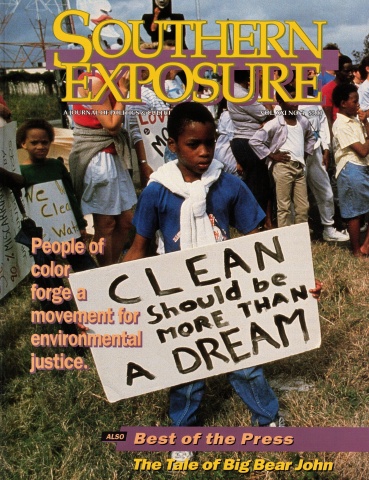

The environmental justice movement in the South, like every grassroots movement, is made up of individual struggles in small towns and cities involving years of hard, painstaking work. We've collected stories of communities of color fighting for a clean, healthy environment in each state of the region. A few begin in "From Coalitions to Conquistadors" on page eight; the rest are featured here. Many of these stories are told by the citizens most involved in the struggle. Some tell of tackling incinerators or oil tank farms; others of staging demonstrations, building coalitions, or pushing for tougher laws. But all share the vision voiced by Pat Bryant of the Gulf Coast Tenant Organization: "We seek a world in which the interests of corporations are subordinate to the needs of people. We envision and will struggle for a 'beloved society.'"

“Mutual Trust” – Louisville, Ky.

When Louisville Mayor Jerry Abramson announced plans to build a new solid waste incinerator back in 1990, the proposed location came as no surprise to local residents. Rubbertown, a neighborhood on the west end, has long been dominated by large factories such as B.F. Goodrich, du Pont, Rohm and Haas, and American Synthetic. What's more, the surrounding communities are populated primarily by low-income and African-American residents.

Residents were outraged. ''They don't need to put anything else down there; they've already got enough things contaminating Rubbertown," said Rosebud Taylor. "The projects that nobody else wants are stuck in the black or poor neighborhoods," added Frank Jones.

Jones, Taylor, and other members of Kentuckians for the Commonwealth (KFTC), a statewide citizens group, decided to fight the incinerator. With a local environmental organization, they developed an alternative recycling and source reduction plan that would cut pollution and save the city millions of dollars. But Louisville Energy and Environment, the incinerator company, hired a professional public relations firm to promote its "state-of- the-art waste-to-steam" facility with videos and glossy brochures.

To counter company propaganda, KFTC turned to cross-racial organizing. The group had worked with POWER, an African American-led group with members in the west end, on a campaign to end utility shutoffs to low-income residents. The two organizations agreed to team up again, combining work on utility reform with efforts to defeat the incinerator.

The multi-issue approach proved mutually reinforcing. When POWER convinced the Board of Aldermen to hold a public hearing on utility shut-offs just a mile from the proposed incinerator site, for example, KFTC scheduled a press conference at the site immediately following the utility hearing. That way, people concerned about both issues could conveniently attend both events. Both stories made the top of the news that evening.

“We developed a relationship of mutual trust and together worked for the victory,” says KFTC member Tyler Fairleigh.

POWER and KFTC held their meetings in the west end, allowing neighborhood leaders to chair gatherings and speak to the media. Local residents recruited their neighbors, educated their churches, and collected signatures on petitions. To keep up the public pressure they held news conferences, organized rallies, attended public hearings, staged public skits, and negotiated with city officials.

Within a few months, all four African-American aldermen joined in opposing the incinerator. Other city leaders followed suit, citing economic and civil rights concerns. Rather than risk the embarrassment of a defeat, the mayor abandoned the incinerator proposal. The aldermen eventually voted to implement part of the alternative recycling plan developed by KFTC.

Newly organized residents say they will continue to fight for environmental justice. “It doesn’t take a rocket scientist to realize this is environmental racism,” says Mary Woolridge, a KFTC member. “I see absolutely no reason to build an incinerator anywhere in Louisville or in Jefferson County.” —Terry Keleher.

Terry Keleher is a community organizer and KFTC member in Louisville, Kentucky.

Legislating Justice—Charleston, S.C.

Nearly everyone in the four black communities that make up the Neck area of Charleston, South Carolina can name someone who has cancer or has died of cancer. In the heavily industrialized stretch along the Ashley River north of the city, infant mortality rates are high and nearly everyone suffers from respiratory problems and nose and eye irritations.

The state Department of Health and Environmental Control blames the health problems on lifestyles, but residents insist that the polluting industries near their homes have contributed to their ailments. The area hosts the Albright & Wilson Americas chemical plant, where a 1991 explosion killed nine people; a trash incinerator from the nearby Charleston Naval Shipyard; the Macalloy Corporation steel plant, fined several times for pollution violations; two trucking depots; several oil storage facilities; and Interstate 26, a major transportation corridor that crosses the communities.

"We're at a disadvantage because we're a black community," says Jennifer Jackson, a 35-year-old resident. "For over 100 years these companies have gotten away with murder because they provide a major tax base for the city. These people do anything they want to us and no one seems to care."

Throughout South Carolina, the environmental struggles of poor and predominantly black areas like the Neck are the rule rather than the exception. Recent data compiled by the Citizen's Local Environmental Action Network, a statewide environmental group, show that most waste disposal facilities are located in or near black communities - including all but two of the 23 sites that made the EPA Superfund list of deadliest waste sites.

"Environmental racism is no fairy tale," says State Representative Ralph Canty. "There's no doubt that those who breathe dirty air and drink dirty water are the poor, the disadvantaged, and the black."

To alleviate discriminatory practices in siting toxic and hazardous facilities, Canty introduced the Environmental Justice Bill in • the state legislature this year. Patterned after federal legislation introduced by Representative John Lewis of Georgia and then-Senator Al Gore of Tennessee, the bill would curb the siting of polluting industries in areas already devastated by poverty, crime, and other social ills.

Other Southern states are also moving forward with similar measures to ensure environmental justice:

Arkansas passed an “environmental equity” law last April mandating that waste facilities be located at least 12 miles apart. But the law exempts some facilities and allows projects to proceed if they present economic benefits to the host communities.

Georgia lawmakers are considering an Environmental Justice Act that seeks to ensure "that significant adverse health impacts associated with environmental pollution in Georgia are not distributed inequitably." The bill requires officials to publish an annual toxics release inventory, assess health risks, and compile a list of 20 areas facing the greatest environmental threat.

Louisiana passed a law in June 1993 requiring the state Department of Environmental Quality to hold public hearings on environmental justice and make policy recommendations to the legislature. The law also mandates that particular attention be given to populations without "the economic resources to participate in environmental decisionmaking affecting their community."

North Carolina is considering a bill that would establish an Environmental Justice Commission to examine state environmental policies and siting patterns based on socioeconomic and demographic data. The commission would also study policies to assure fairness and public participation in environmental decisions affecting low-income and people-of-color communities.

Virginia has ordered the legislative audit and review commission "to study ... siting, monitoring, and cleanup of solid and hazardous waste facilities, with an emphasis on how they have been operated and how they have impacted minority communities." The findings will be presented to the governor and general assembly in 1995.

In South Carolina, however, the Environmental Justice Bill has stalled in a House subcommittee. "The knock on this bill is that it's a 'black bill.' Nothing could be further from the truth," says Canty. "Whether it's a black community in Rock Hill fighting an incinerator 97 feet away from their church or a white community battling groundwater contamination at Langley Pond in Aiken, the issue is justice. No one deserves to be dumped on because they are poor or minority."

Canty says he plans to reintroduce the measure next year. "It may not pass this year or the next year or the next year, or even the next year after that, but I'll keep introducing it until the problem of environmental racism gets the attention it deserves.” — Ron Nixon.

Ron Nixon is a contributing editor for Southern Exposure in Columbia, South Carolina. Information on state legislation was provided by Richard Regan and John Choe at the Center for Policy Alternatives in Washington, D.C.

In the Valley—Institute, W.Va.

In December 1984, West Virginia residents of the Kanawha Valley watched their televisions in disbelief as video images on the evening news conveyed the aftermath of the chemical disaster at the Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India.

More than 3,500 people died and 50,000 were injured when the factory leaked methyl isocyanate (MIC) - the same chemical being manufactured and stored by Union Carbide in the predominantly African-American college town of Institute, just outside of Charleston.

Officials at the Institute plant immediately tried to assure residents that a "Bhopal-like incident could never occur here." But most plant managers did not live in the Institute area, and they had inadequate emergency plans for evacuating residents in the event of a catastrophe.

In early 1985, residents created People Concerned About MIC. PCMIC demanded more information about chemicals affecting the community, called for the reduction of toxic waste emissions, and pressured officials to build an emergency evacuation route.

The disaster was not long in coming. In August 1985 - just nine months after the Bhopal tragedy - an accident at the plant released 500 gallons of highly toxic chemicals into the atmosphere, sending 135 Institute residents to area hospitals. Plant officials waited 20 minutes before warning the community.

"The first thing that crossed my mind was India," said one worker. "You're so helpless. There's nothing you can do. I mean, how far can you run?"

The accident divided the community. Plant workers who feared for their jobs supported the company, while members of PCMIC protested the policies and practices of Union Carbide.

In recent years, however, more and more chemical workers in the area have begun to support community organizers. In August 1992, an explosion at nearby Rhone-Poulenc released 45,000 pounds of chemicals into the air, killing one worker and seriously injuring two others. Chlorine leaks from the same plant injured 19 workers in May and five workers in September 1993.

"As a labor union we are interested in working with groups like People Concerned About MIC," says Steve White, director of Affiliated Construction and Trades. "We found that companies that cut comers with their workers are damaging the environment and deceiving communities they operate in."

PCMIC has also worked on building multi-racial alliances. The predominantly African-American group has allied with white and Jewish groups threatened by pollution from 12 factories along the Valley. Together, they have pushed for a health survey and emergency preparedness measures, educated residents, and lobbied for a state law to reduce toxic emissions.

"Other groups have become aware of our mutual interests, which are to sustain jobs and protect the health and safety of workers and plant neighbors," says Paul Nuchims, a professor at West Virginia State College and a member of PCMIC. "By working together, we are better able to help companies envision and achieve long-range environmental goals." — Pam Nixon

Pam Nixon is president of People Concerned About MIC and a health care worker in Charleston, West Virginia.

Toxic Trucking—Martinsville, Va.

Last year residents of Martinsville, Virginia, a small town nestled in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains, discovered that trucks hauling toxic waste for an Oklahomabased company were using a local abandoned trucking facility as a stopover. Unknown to city officials and local residents, Environmental Transportation Service (ETS) had set up business a year earlier in the heart of the only black neighborhood in town.

Michelle Smith, a local environmentalist, and Bob Sharpe, an investigative reporter for a cable television station, exposed the company on a nightly talk show. Outraged, citizens quickly formed SCAT - Sensible Citizens Against Toxics - to fight the toxic way station.

When SCAT held a town meeting at Fayette Street Christian Church, the group proved to have overwhelming support from a large cross-section of the city - black and white, rich and poor alike. Local ministers lent their support, as did regional and national environmental organizations.

But city officials supported the company, claiming that ETS was protected by zoning laws. A company official called citizens who opposed the toxic truck stop “troublemakers and vigilantes,” adding that “they are just making a mountain out of a molehill.”

Yet SCAT’s persistence paid off. As a result of the citizen organizing, the city now requires companies to get a special permit to park vehicles containing toxic waste. State legislators passed a zoning amendment that would oust such facilities, but the city council has not conformed to the new law.

“We’re back to the drawing board,” says SCAT’s Michelle Smith. The group plans to approach the legislature again to ask for a stronger law that the city would have to pay attention to. “We’ll do everything we can,” says Smith, “to get a law that protects the neighborhood.” —Gloria Hodge-Hylton.

Gloria Hodge-Hylton is a former educator and founding member of SCAT who lives in Martinsville, Virginia.

SOS at SRS—Savannah, Ga.

Mildred McClain has a Ph.D. from Harvard, but she hasn’t forgotten the lessons she learned growing up in a public housing complex in Savannah, Georgia. “People of color in Georgia are treated no differently than people of color anywhere else in the world,” she says. “Our neighborhoods are the dumping grounds for all kinds of hazardous wastes.

One of the biggest dumping grounds is the Savannah River Site (SRS), a 300-acre nuclear weapons factory opened near Aiken, South Carolina in 1952. Local residents have long been threatened by leaks and mishaps at the facility, which sits atop one of the largest aquifers in the region. Tritium from the plant has been found in well water and the milk of cows as far as 120 miles away in the predominantly black community of Keysville, Georgia.

About five gallons of tritium-contaminated water leaked into the river in 1991, forcing oyster beds to close. SRS and federal health officials denied that the tritium posed a health risk, but many residents are skeptical.

“We still don’t believe that the people are being told the truth about the damage that's been done to their health by the leaks, spills, and emissions from the SRS," says McClain, head of Citizens for Environmental Justice (CFEJ) .

Operating on a shoestring budget since its beginning in 1991, CFEJ members have educated the public about the possible health risks of contamination from the SRS through workshops on radiation exposure, a weekly radio show called "Black Earth Watch," and statewide conferences. They helped put environmental racism on the agenda at the first joint meeting of the Georgia Association of Black Elected Officials, the Georgia Conference of Black Mayors, and the Georgia Legislative Black Caucus.

In January 1993, CFEJ members nearly caused a traffic jam in downtown Savannah when they held a loud, colorful protest in front of City Hall, carrying signs lambasting SRS and wearing white Halloween masks symbolic of death. In July, the group led a caravan of environmental activists to SRS for a tour and briefing to dispute the safety of the facility.

CFEJ has also served on advisory committees overseeing SRS and studying its emissions. Members met with Secretary of Energy Hazel O'Leary and demanded that the site halt all production of tritium. And they are currently fighting a proposal to tum the facility into a national processing center for tritium and to resume production of plutonium.

"We are sick and tired of being a dumping ground for other people's hazardous waste," says McClain. To stop the polhition, she adds, CFEJ is working with a diverse network of community organizations and international coalitions.

"Fighting for environmental justice goes beyond traditional environmental issues," she says. "It includes all the issues we face in our community. It's going to take the collective work of all sectors of our community to win this one." -Theresa White

Theresa White, a Savannah native and former journalist, currently manages the Savannah District Office for Representative Cynthia McKinney.

Death Holes—Little Rock, Ark.

One Sunday afternoon last May, 16- year-old Emanuel Ray Holloway drowned in an old mining pit between Higgins and Sweet Home, two black neighborhoods on the southeast side of Little Rock, Arkansas. News accounts said the youngster went to the pit to learn how to swim.

The death was tragic - and all too familiar. Children have been dying in the "blue holes" in this low-income community for at least 30 years. A 1964 news story called two bauxite pits abandoned by aluminum companies "large enough to set the state Capitol in several times over."

Abandoned mines aren't the only environmental danger. Since 1971, the city has dumped its garbage in a bauxite pit donated by Reynolds Metals Company, which has created a rat and vermin problem. To make matters worse, state officials also planned to allow a commercial medical waste incinerator to be built there.

"They wanted to put it near two schools, two churches, a day care center, and a convalescent home," says Don Buchanan, who has lived in Higgins for 17 years. "They are not concerned at all about poor people. There are over 4,000 people in the community, but the people who profit from this dumping are not concerned about the area."

Buchanan, who is African American, says the community is the target of dump sites and incinerators because "it is 99 percent black." Melissa Price, a white resident, agrees. "If this were happening off Shackelford, off Markham, or in the Highway 10 area, it would have been stopped before it ever got started," she said, alluding to Little Rock's affluent west side.

Community organizing and activism have helped stem the tide of pollution over the last decade. Residents successfully blocked two landfills proposed by a state senator from being located in the area. The state Department of Pollution Control and Ecology deemed the proposed site unsuited for a landfill - but a year later granted a permit for a medical waste incinerator in the same area without any public notice.

Residents blame politics for the turnaround. The incinerator is represented by the powerful Rose Law Firm, which once employed Hillary Rodham Clinton and supplied President Clinton with his associate U.S. attorney general and several White House counsels.

Randall Mathis, state director of pollution control, insists that big names did not enter into the decision. "We don't make political decisions," he says. But last October, things turned around again. Responding to citizen pressure, Mathis revoked the incinerator permit.

Citizens are reserving celebrations and continuing the fight until they are sure the incinerator is gone for good. "We won't rest easy while there's still the possibility they can appeal to a higher power," says Melissa Price. -Bobbi Ridlehoover

Bobbi Ridlehoover has been a reporter in Little Rock for 12 years.

Networking in Texas—Dallas, Texas.

Brenda Moore looked into the camera and explained the botched efforts to clean up lead contamination in her westside neighborhood of Dallas, Texas. "This is environmental racism pure and simple," she said. "If this had been a white neighborhood, everyone would have been packed up and moved out of here. They come here and 'clean up' our neighborhoods with their suits on, but they let people just sit there as they stir up the dirt."

Moore's story is being used to stir up the dirt beyond her own neighborhood. Rene Renteria, a member of People Organized in Defense of Earth and her Resources (PODER), videotaped Moore and her father, the Reverend R.T. Conley, to document the second EPA-mandated cleanup of lead contamination in West Dallas. The video serves as an education and organizing tool, informing people of color in other parts of the state about the struggle.

Moore, Conley, and Renteria are all members of a statewide coalition called the Texas Network for Environmental and Economic Justice. The network got its start in 1991, when African- American and Latino activists met to examine the impact of toxins on their communities. They represented groups from all over the state, working on issues ranging from lead contamination to relocation of polluted communities to the dangers of landfill expansion.

The next year the network held its first statewide gathering in Austin, bringing together more than 70 activists from across Texas and northern Mexico. The gathering gave organizers a chance to share information in workshops on environmental racism, state environmental and public health agencies, the North American Free Trade Agreement, economic development, and workplace toxins. Since its formation, the network has been instrumental in disseminating information and providing support to groups across the state. “When PODER initiated its campaign against Exxon to remove its tank farm from our East Austin community, the people from the Texas Network helped in sending letters to the president of the company urging him to remove the tanks,” explained Sylvia Herrera, a PODER member. “When we started the Exxon boycott, the network helped us get the word out.”

The campaign worked. Last February, Exxon was the last of six oil companies to agree to move its facility away from homes and schools in the Latino and African American neighborhood, and to clean up the mess it made.

The network also spurred the development of the Texas Task Force on Environmental Equity and Justice, a state panel that recommended policies to address the disproportionate impact of environmental hazards on communities of color. Alice Flores, a community leader from Rosenberg and a member of the network, was named to the task force.

"We are at the point where we are developing expertise on environmental issues in our communities," says Arthur Shaw, a Houston member of the network and a long-time civil rights activist. "The Texas Network is becoming a resource for communities of color in the state affected by environmental hazards. As we build our collective know-how, we need to make sure we share those skills with other communities that are working for environmental justice.” —Antonio Diaz.

Antonio Diaz is the coordinator of the Texas Network for Environmental and Economic Justice, co-chair of POD ER, and a staff member of the Texas Center for Policy Studies in Austin, Texas.

Superfund City—Chattanooga, Tennessee.

In recent years, local officials in Chattanooga, Tennessee have launched a national public relations campaign. The goal: to attract environmental conferences and conventions to town and shape a new civic image as “The Environmental City.”

But residents in the predominantly black neighborhoods of Alton Park and Piney Woods have a different perspective. The area around their homes contains 42 toxic waste sites, including a toxic dump 100 times larger than Love Canal, a playground, and a baseball field sometimes submerged from a contaminated spring. Nearby is a defunct coking plant where numerous chemicals—including leukemia-causing benzene—have been found in the soil and groundwater.

Chattanooga Creek, which flows past miles of polluting industries before reaching Alton Park, is considered by many researchers to be the most polluted stream in the Southeast. Lined from bank to bank with tarry goo, the entire creek bed has been declared a state Superfund site and is currently being evaluated for ranking on the National Superfund Priority List.

“Had this happened anywhere else, the cleanup would already have begun and they would be talking about relocating people,” says Jean Stone, a member of the Stop Toxic Pollution group. Residents formed STOP in 1988 to push the city to clean up the air and water pollution in the community.

The city proved reluctant to act. “I think Chattanooga officials are afraid if they admit the problem, they’ll somehow be taking the blame,” says David Brown, a STOP organizer. “Why can’t they just say publicly that it’s an injustice and a shame to Chattanooga and stand at the front of the cleanup effort?”

When local officials didn’t respond to initial protests, the group got help. In 1990, STOP teamed up with Greenpeace and the Environmental Research Foundation and released a report highlighting the severe contamination and environmental racism in southside neighborhoods.

The resulting publicity spurred elected officials to urge EPA to take action. In 1991, the agency announced a “geographic initiative" to begin a cleanup. The city agreed to rebuild its sewer lines to stop raw sewage from flowing into the creek during heavy rains. And the Agency for Toxic Substance and Disease Registry began the first-ever look at health risks in the community. Last summer the agency mounted a public campaign to keep youngsters away from Chattanooga Creek - an ominous forewarning of what the final assessment is likely to conclude.

Local industry is also starting to listen to community concerns. According to STOP, a company called Velsicol is inviting community leaders to regular meetings and talking with them about efforts to update plant equipment and cut pollution.

Despite such progress, however, many officials remain reluctant to address the reality of environmental racism. After members of the state Environment and Conservation Committee told State Representative Tommie Brown that they were unaware of the community's decades-old problems, Brown invited Alton Park residents to testify. All but three members of the committee left the meeting before the residents could tell their stories.

In the long run, residents say, they are placing their faith in community organizing and tougher laws. "We're encouraged not by the companies and the local officials, but by the avenues out there for Superfund cleanup, and by the environmental justice bills before Congress," says Jean Stone. "Environmental racism was very much alive here in the past, and it's still here today. We have to recognize it and keep the eyes of the people focused." – Pam Sohn

Pam Sohn is a writer based in Chattanooga, Tennessee.