Tenants and Toxics

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

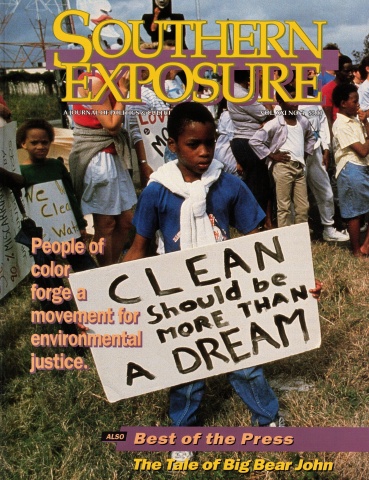

This is my story about how as a tenant organizer I became involved in the fastest growing movement in the United States. Mine is a story of how the greatest crisis facing civilization today - environmental destruction - demands leadership, vision, and solution from people of color. It is a story of how African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Native Americans across the nation have become pivotal to saving the Earth. It is a story of how the struggle against racism and greed is the key to stopping the destruction of people everywhere.

My views evolve from my childhood in North Carolina in the 1950s, when I tagged along with my father, a Baptist preacher of the social gospel. Nowadays we call it liberation theology. I had grown up in a housing project and soon got absorbed in tenant rights.

The tenant rights movement was an important part of the civil rights movement in the late '60s and early '70s, surviving crushing blows from the FBI and CIA. In the early '80s, the Reagan-Bush plan to demolish public housing or sell it to private landlords brought an upsurge in organizing. I moved to the Deep South to assist this work, with support from the Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice (SOC) and the Institute for Southern Studies.

The Gulf Coast Tenant Organization developed in Alabama, Mississippi, and Louisiana and won victories for tenant rights in many communities. We also joined struggles against racist and sexist landlords and housing authorities, with national battles to cut military spending so there would be money for housing.

Then in St. Charles Parish, Louisiana we learned an important lesson that mitigates further against single-issue organizing. Here African-American leaders battled the housing authority and won major renovations to public housing, refund of overcharged rent, overturn of illegal arrests of demonstrators, and firing of the insensitive housing administrators.

After this victory, however, Vanessa Preston, Ruth Bovie, and other St. Charles leaders pointed out that they were being poisoned each day by giant factories owned by multi-national corporations located virtually on their doorsteps. They said their victories would be meaningless unless the same power used to beat plantation housing managers was turned against petro-chemical companies.

We realized that similar conditions existed all along the industrial corridor between Baton Rouge and New Orleans, which we later helped christen "Cancer Alley." Some 138 factories were huddled around mostly African-American and some poor white communities. They were producing fertilizers, pesticides, plastics, herbicides, electricity generated by nuclear power, gasoline, and hundreds of petroleum-based products - products at the center of almost everything produced in the U.S. and abroad.

Children in our youth groups had year-round eye infections that doctors called pink eye, which we later associated with acrolein, a Union Carbide chemical. We witnessed leaders we trained like Ruth Bovie, their relatives, and friends become ill and die of cancer. The poverty was strikingly similar to conditions in Central America, Africa, and Asia. Communities lacked running water and sewage disposal; people were poorly educated; public housing was deplorable. The poisoning companies refused to hire people from the host communities. More black men were in prison than in college. This was our reality.

When the Superfund law with its community right-to-know provisions was reauthorized in 1986, we began to find out what chemicals, and how much, were being dumped on us. Before that, EPA and the companies kept saying they could not divulge "trade secrets."

Through what became a sister organization, the SouthWest Organizing Project, we learned that similar conditions existed for Latinos in the Southwest, and for Native Americans struggling to save their sacred earth and win sovereignty. All communities of color were facing the same crisis.

Blind Spots

The movement against environmental racism had actually started in 1982 when people in Warren County, North Carolina stood in front of trucks to keep PCBs out of their community. In 1987, the landmark study of the United Church of Christ, Toxic Waste and Race in the United States, confirmed the grim fact that race was the most significant factor determining where commercial hazardous waste facilities are located. The higher the concentration of people of color, the more poisoning facilities. Traditional environmentalists were unable to digest the significance of this. I knew their racial blind spots were going to be tough to penetrate.

Yet we realized that white working class people should be our natural allies. We understood that tradition, racial prejudices, white privilege, and racist propaganda affect all whites, including the working class. But we were determined to seek historic opportunities to highlight the self-interest of all ethnic groups.

That was especially true during 1988. First we organized a busload of mostly African-American tenants, along with some environmentalists, to attend the Southern Environmental Assembly in Atlanta. Environmental racism didn't make it onto the agenda, but we shattered the myth that African Americans were not concerned about the environment. A collaboration developed between Gulf Coast Tenant Organization, Greenpeace, the Oil, Chemical and Atomic Workers Union, Louisiana Environmental Action Network, and several community and civil rights organizations.

From Toxic Release Inventory data, we discovered that the area between Baton Rouge and New Orleans - Cancer Alley-was one of the most poisoned places in the U.S. We organized an 11-day march that included significant media events.

Blacks and whites were working together; it was a significant breakthrough. But before that march was over, racial tensions strained and tore at its inner fibers. White groups proved unable to focus on the disproportionate poisoning of African-American communities and the resulting need for them to follow black leadership.

We knew that the road ahead would be lonely. Whites can play a significant role in the new movement we are building, because they too are being poisoned and must deal with the additional poison of racism in their communities. But we in communities of color must lead this movement because our history, our struggle, and the reality of our lives have compelled us to develop a total approach to society's problems that is the only way to stop the poisoning of the earth.

As long as communities of color provide "safe places" to produce deadly products and store their waste, our economy will keep on making more poisons. It is already making more than this earth or our communities can sustain; thus poisons will continue to spill over into poor white communities. As people of color deny those "safe places," we will force basic changes in production processes and priorities. But we won't get to that point as long as people of color here and abroad are seen as less than human and not as deserving as whites of education, health care, jobs, housing, and fair police protection.

So we have redefined the "environment" to include everything which impacts upon where we live, work, and play. It thus becomes the mission of people of color to lead this movement and make our nation aware of its self-interest in our struggle. When we win, we win for everyone.

Our new definition of the environment is akin to the perspective of indigenous societies in Africa, Asia, South and Central America where we see respect for all life and the sacredness of all things in the natural order.

A New Agenda

Beginning in 1988, we took our definition of environment to SOC for regional support. Dr. Bob Bullard, in his book Dumping in Dixie, revealed that 65 percent of the nation's commercial hazardous wastes were dumped in the states of the Old Confederacy, inostly in African-American communities. SOC had helped initiate the Gulf Coast Tenant Organization in the early '80s, and many times its regional network made the difference in local struggles that otherwise would have been isolated and snuffed out. SOC also had a long history of dealing with racism and taking on the tough questions of how to reorder society's priorities. Its network of activists expanded their work from economic, racial, and social justice to include environmental justice.

In January 1990, the Gulf Coast Tenant Organization authored a letter challenging the "Big Ten" national environmental groups to deal with issues facing communities of color. The letter was co-sponsored by the Southwest Organizing Projects and endorsed by civil rights groups. We didn’t intend it to be publicized, but Phil Schabecroft, then at the New York Times, ran a prominent column in which the “Big Ten” admitted that they had a major problem because they had mostly white staffs and lacked the perspectives of people of color.

One outgrowth of this letter was the October 1991 National People of Color Environmental Summit. Along with the Southwest Organizing Project, which organized the Southwest Network for Environmental and Economic Justice (SNEEJ), and other grassroots activists, we insisted that this Summit be directed by grassroots movements. More than 500 delegates—Native Americans, Pacific Islanders, Latinos, African Americans, and Asian Americans—came together, sharing histories, cultures, and perspectives in the context of environmental degradation. They confirmed the existence of an international, multi-cultural, multi-issue movement; adopted 17 Principles of Environmental Justice; and changed the environmental movement in the U.S. forever.

Delegates decided against establishing a national organization at that time. Instead they mandated regional initiatives to respond to our community crises. In the South, SOC provided the cohesion. In 1992, Damu Smith, on loan to SOC from Greenpeace for the entire year, along with Connie Tucker and several volunteers, traveled in 14 states from Texas to North Carolina, visiting communities previously isolated by race and geography. We learned that there was hardly a community in the South that wasn’t struggling against a landfill, incinerator, toxic dump, or polluting industry.

Culminating this year-long work, SOC sponsored a regional conference in New Orleans, hosted by Gulf Coast Tenant Organization and Xavier University, which was working with the tenants on environmental problems. The event attracted 2,500 people, mostly activists from African-American, Latino, and Native American communities, along with a significant number of working class whites and more than 500 youth. The diversity resulted from collaboration between SOC and two other major networks—SNEEJ and the Indigenous Environmental Network. Government and industry were shocked at the tremendous turnout, which more than doubled our predictions. It was the largest environmental gathering on record in the United States.

At that conference and a follow-up gathering in 1993, we noted a shocking fact: The areas with the most poisoning are the very same areas where we have elected the most African-American and Latino officials. We developed a Code of Environmental Ethics to demand that officials of color, as well as whites, be accountable to our environmental health.

Also at the 1992 conference, we introduced for discussion across the South a Southern Manifesto, presenting a radical agenda that can save our communities, our people, and the planet. It calls for a total moratorium on new poisoning facilities in the South; massive clean-up of damage already done, tied to training, jobs, and economic development; drastic cuts in military spending; massive housing construction; an overhaul of our educational system; health care for all; and foreign policy that precludes dumping on and exploitation of developing countries.

This is an agenda that comes out of struggles of people of color and working class people at the base of the society. It places the mantle of leadership squarely on our shoulders. But it is a program that can rebuild America and save all our people. Many of us are willing to die, if necessary, to eradicate racism. If whites can see that our program offers them salvation too, we may see a mass repentance in our racist society that, in the words of the '60s song, can "make that day come round."

Delegates to the SOC conference recognized a great disparity between existing. capacity of local organizations and what is needed to accomplish our own agenda. They recommended information exchange and action networks; technical assistance, including funding and computer support; leadership development; and support to groups developing sustainable community-based economic enterprises. The time has come to engage communities of color and poor white communities across the South in a massive campaign to develop our rich human and material resources from the bottom up. There is broad-based grassroots commitment to creating viable economic alternatives to the region's persistent poverty, which makes us vulnerable to exploitive and poisoning industries.

Now we must all use our time-tested workshop models and organizing assistance in communities throughout the South. As we help them push for societal policies and changes, as we encourage them to develop a vision of a new society, we will also help develop the skills of local leaders and organizations so that they become economically self-reliant.

We are dealing with a moral issue. Many white churches are woven into the maze of corporations that poison us. Many religious institutions hold profitable stock in poisoning companies. CEOs of poisoning companies are often outstanding church members. Whatever happened to the Commandment "Thou Shall Not Kill"? What about New Testament teachings, "You are your brother's (and sister's) keeper," and "Love your neighbor as yourself'?

These are the same churches that have retreated from any commitment made in the '60s to deal with racism. We must preach the gospel of environmental justice to help religious communities develop the spirituality that has been ours for centuries to offer America. Our youth organizations, educational institutions, and labor organizations must also join the front lines of this battle.

The "Principles of Environmental Justice" and the Southern Manifesto call for the industrialized and non-industrialized communities and nations, the rich and poor, to share equitably in resources - jobs, income, leisure, education, housing, health care, and a clean environment. We seek a world in which the interests of corporations are subordinate to the needs of people. We envision .and will struggle for a "beloved society" free of war.

In his book Stride Toward Freedom, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote: "When the history books are written in future generations, the historians will have to pause and say there lived a great people, a black people ... who injected new meaning and dignity into the veins of civilization."

Today Dr. King's prophecy can be paraphrased to say: "There lived people of color on this continent who projected a vision that turned our whole society in a more humane direction." This is our vision in the environmental justice movement.

Tags

Pat Bryant

Pat Bryant is a writer, community organizer, and director of Gulf Coast Tenant Organization, which operates in poor African American communities in Alabama, Louisiana, and Mississippi. He is a board member of SOC and the Institute for Southern Studies in Durham, NC.

Pat Bryant is an editor of Southern Exposure and field organizer for the Southeast Project on Human Needs and Peace. (1982)