The Stroke Belt

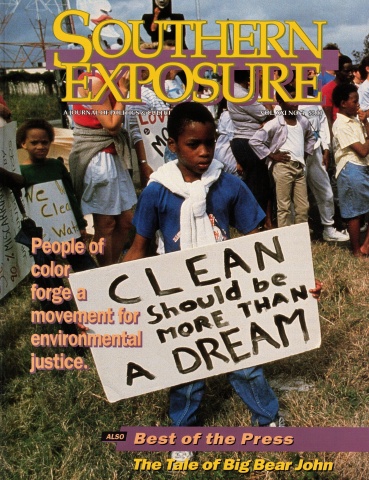

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

One disabled Virginia-born Woodrow Wilson at the peak of his presidency, another killed Hillary Rodham Clinton's father, and they continue to ravage the South at higher rates than any other region. They are strokes, a condition caused when blood clots or fat deposits deprive brain cells of oxygen, causing paralysis or death.

Although stroke rates nationwide have declined dramatically in the 20th century, strokes are still the third largest killer in the nation. Ten of the 12 states with the highest death rates from strokes are in the South, with South Carolina ranking first.

"The places of high stroke mortality have been in the old Black Belt, farmer, plantation economy areas," says Steve Wing, an epidemiologist at the University of North Carolina in Chapel Hill. The coastal plain long experienced the highest stroke rates, but with coastal development, higher rates have shifted westward to farmland in the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.

The factors that cause strokes are closely intertwined with elements of Southern culture, from tobacco and fatback to race and poverty. Smoking, for example, is highest among Southern men. "Smoking definitely increases the risk for buildup of plaque in your arteries, and that's the leading cause of stroke," explains Norman Oliver, a writer and editor at the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke.

Black Southerners suffer higher stroke rates than whites, and studies show that stresses related to poverty and racism - "suppressed hostility, thwarted aspirations, and raised blood pressure" - may increase the risk for African Americans. "If you're of a low socioeconomic group, you're less likely to go to the doctor and be told you have high blood pressure," says Oliver. "If you do go and you're prescribed medication, you're less likely to be able to afford it." Greasy Southern cuisine can also create the fatty plaques that contribute to stroke. "People in the South have diets that traditionally depended on the foods that were discarded by the rich, like pork fat and intestines," says Steve Wing.

Prominent black nutritionists have tried to educate African Americans about the danger of soul food. Comedian Dick Gregory, who has written diet books and tarted a diet program, describes fatty food as black genocide. 'The quickest way to wipe out a group of people," he says, “is to put them on a soul food diet."

In her vegetarian cookbook Soul to Soul, Mary Keyes Burgess says that she stopped cooking with pork after she realized "that eating animal fat may have partially contributed to the fact that many of my family were suffering high blood pressure." There are medical ways to fight strokes. Aspirin cuts the risk by 80 percent in some patients, non-surgical angioplasty opens blood vessels and prevents clots, and surgery can remove fatty deposits from neck arteries. But with stroke, health officials say, an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure.

"We' re trying to alert people to the prevention aspect," says Jan Frye-Pierson, a

nurse clinician at the Stroke Clinical Research Center in Winston-Salem, North Carolina. "If they have one of the warning signs, it's just as important to go to the doctor as if they have chest pains." Frye-Pierson spends much of her time on the road talking to community groups, and the center has set up an information hotline to answer questions.

Disability, job loss, and depression can follow a stroke, and patients and their families often need both physical and psychological therapy to get back on their feet. Bruce Harrison of Winston-Salem lost some functioning on his left side when he suffered a stroke four years ago. "It was terrifying," says his wife Jackie. But with the help of a support group at the Stroke Center, she says, "we're doing much better."

Her husband Bruce recommends his own, particularly Southern brand of therapy for stroke victims. "It helps to be ornery," he says.

Tags

Mary Lee Kerr

Mary Lee Kerr is a freelance writer and editor who lives in Chapel Hill, NC. (2000)

Mary Lee Kerr writes “Still the South” from Carrboro, North Carolina. (1999)