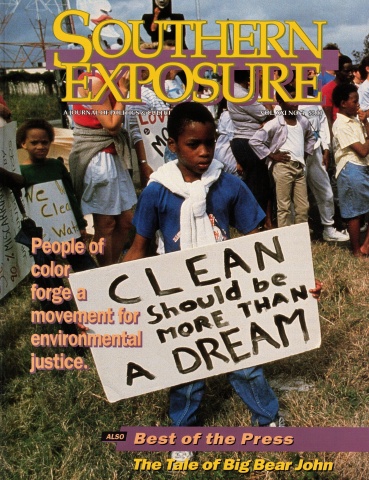

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

On a cool evening last March, nearly 300 environmental justice activists from across the South gathered in a hotel in Hattiesburg, Mississippi. The Southern Organizing Committee for Economic and Social Justice (SOC) was convening a gathering the next day in nearby Columbia to support local residents fighting to clean up hazardous wastes at an abandoned factory. The meeting would also give organizers a chance to network and strategize.

Before the meeting began, the Institute for Southern Studies and Southern Exposure invited organizers from nine states to join our executive director, Isaiah Madison, for a frank discussion of issues facing the environmental justice movement. We wanted to know about their local struggles, and about ways to link them to regional organizing. We wanted to understand the obstacles they face, and their hopes for the future. Most of all, we wanted to know how activists at the grassroots - black, white, and Native American - envision building a broad and powerful movement for environmental justice.

Around the Table

John Michael McCown with the Sierra Club in Birmingham, Alabama, and Nick Aumen in Lake Worth, Florida.

Cynthia Smith and Guy Jackson with Citizen’s Clearinghouse for Hazardous Waste in Atlanta, Georgia.

Doris Beale and Mattie Mathis with the Kentucky Alliance against Racial and Political Oppression in Louisville.

Scott Douglas with Greater Birmingham Ministries in Alabama.

Rose Mary Smith, Betty Ewing, and Pat Bryant with the Gulf Coast Tenant Organization in New Orleans, Louisiana.

Delois Gore with African American Environmental Justice and Protect Our Environment in Noxubee County, Mississippi.

Virginia Sexton and Mike Sexton with Wake Up in Cherokee, North Carolina.

Anne Braden with SOC in Louisville, Kentucky, and Connie Tucker in Atlanta.

Benishi Albert with SOC and the Indian Land Toxics Campaign in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

Scott Morrison with Jobs and the Environment Campaign in Ada, Oklahoma.

Starting Local

Isaiah Madison: Let's talk about the local struggles first, and then move on to talk about how we network and build a real movement.

John McCown: Cynthia Smith and I had our beginning in Hancock County, Georgia, the first county in the nation to be controlled by African Americans since Reconstruction. In 1987, the county was targeted with a proposed $50 million hazardous waste incinerator.

Realizing the dangers with that kind of facility, we began to organize. In five months, we diverted the state's attention from Hancock. Then we visited 10 other communities to show them how we stopped the facility.

That was the genesis of grassroots environmental activism in Georgia. As a result, the governor eventually realized that there was not a need for a hazardous waste incinerator in the state. Following that, we were targeted with a 900-acre landfill. That fight took longer to win, but we were victorious.

Isaiah Madison: How did you do that?

John McCown: There are two kinds of power. You've got to have money or you've got to have people. We didn't have the money, so we knew there was a need for us to go door-to-door. We knocked on practically every door in the community. We came up with fact sheets and invited people to a meeting. Two hundred people turned out the first night, and we educated them.

Another key vehicle we used was the black church, which is extremely powerful in the African-American community. We mobilized the ministers, and as a result they set up a coalition that gave us access to every church in the community.

Isaiah Madison: Did you organize across racial lines?

Cynthia Smith: On the landfill fight we had white participation, but on the incinerator fight it was us.

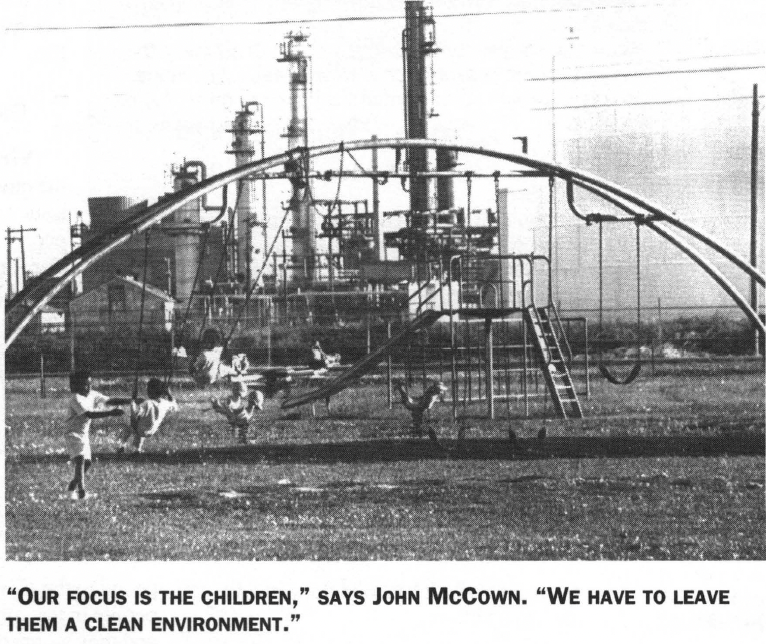

John McCown: Our focus was the children; we have to leave them a clean environment. The white interest was property values. We didn't question their motives - we just wanted their participation and their money.

Guy Jackson: Property value was their incentive, but it took everyone to save the community. Segregation, only working within your own community, is as bad as industry only wanting to profit for itself. You’ve got to reach out and go beyond your own small sphere.

Most groups we work with are multi-racial. But there is a cancer growing within, because some of the black people have been dependent on whites for so long that sometimes they don’t speak out.

Cynthia Smith: It’s a slave mentality. Blacks are working together with whites, but they don’t really have any power in the group. So that’s what we’re working on—trying to build power.

Isaiah Madison: How are you all dealing with it?

Cynthia Smith; We’ve been building brides. In Burke County, where people are fighting a lead smelter, we did a workshop for community leaders. The whites organized it. Only four blacks showed up, compared to about 30 whites. At the end of the meeting they agreed to form multi-racial task forces to go door-to-door to educate the community, but they never went. The white people were telling the black organizers, “Make your people listen,” but they can’t even get blacks to come to the meeting.

John McCown: The black population is saying, “Okay, look, white folks: All these years you haven’t given a damn about us. Now all of a sudden you come in here trying to save our lives. What in the world is this all about? It’s got to be a trick.”

Redefining Environment

Doris Beale: Ours is a different fight in Louisville, Kentucky. We’re fighting violence among the blacks—blacks killing blacks—and we’re working against police abuse and harassment.

Mattie Mathis: We’re working on developing a civilian police review board. The things that police do are so atrocious to the community, especially to the black community. We even have cases of poor whites who have suffered. We have documents of things going back 15 years, and on up to last month when the police killed a man.

Isaiah Madison: Why are people in the environmental justice movement addressing issues of police violence and black-on-black crime?

Mattie Mathis: You have to start with self-preservation. I work in a women's shelter on my job. I see women with children who don't have a place to live. When you have to worry about those kinds of things, that messes with your environment. That takes away the safety. You want to live in a world where the environment is not only safe from lead poisoning but also from police abuse and not having enough to eat and not having a place to stay.

Scott Douglas: I agree. The environment is wholistic. Our movement has always talked about how you can't limit the environment to trees, rabbits, squirrels, and owls. It has to include people and their cultures.

Benishi Albert: Environment is the land, the water, the air. It's the people. It's our communities. It's everything around us.

Betty Ewing: Those of us with Gulf Coast Tenant Organization have been facing many different crises in our environment. A few days ago there was a public hearing in Jackson, Mississippi about the hangings in jails throughout the state of Mississippi. Since 1986 there have been 86 hangings.

Isaiah Madison: How is hanging an environmental issue?

Betty Ewing: The environment is about life, about having choices. Deliberately taking a human being's life is not having a choice.

Rose Mary Smith: We've had many struggles, mainly pertaining to organizing tenants. They were cheating us with rents, lights; they kept letting our buildings go down and they just didn't care. But we cared enough to fight. We knew our community needed to be upgraded even though we are in public housing and are lower-income, because we are human beings. We won, but we keep on struggling. Then they come right in our communities with all these toxic companies killing us. We need clean air, clean land, better food, better quality of life. The rich white folks put out their toxic fumes night and day, pour it into the rivers, and you can't get a decent glass of water. It's just one part of the racism we face in our everyday life.

Organizing Youth

Virginia Sexton: Saving the environment is a health issue - saving the health of people. In Cherokee, North Carolina we have a group called Wake Up, because the Indian people need to wake up and work against the government and the Bureau of Indian Affairs.

We’re small and we have our own government, so we realized its easier to stop things before they get started. When they tried to put an incinerator in the county in 1990, we showed the community a Greenpeace tape about what happened to the Navajos. The traditional people in the community got riled up, and they stopped it.

Then we got ahold of the minutes of a meeting that said the tribal council was going to purchase private deeded land and put a landfill on it. Non-Indians helped us and it was stopped because it would leak into the river.

We also stopped a nuclear depository called MRS - Multiple Retrieval Storage. The military is disarming nuclear warheads, and they have to store them somewhere. We had all kinds of documentation to show they are targeting Indian reservations.

Now we're working on stopping building for tourism along the river. We've got an EPA person opposed to it, but the council just does what it wants. So there's waste going in the river.

Mike Sexton: In the 15 years I've lived in Cherokee, the government has kept saying that we're a sovereign nation. Then they try to put an incinerator on our land, saying they can do it because they're the trustee. The only time I've seen that tribe really sovereign was last week when the snow fell. Snow plows came to the edge of the reservation and stopped.

Scott Morrison: Fighting a hazardous waste incinerator on the Mississippi Choctaw Reservation, I realized that we are targeted because reservation land is exempt from state regulations. Only about 30 of the 300 tribes have a tribal EPA office.

One of the things I'm doing is working on a code of ethics that recognizes that any damage to the environment is damage to our culture, because our culture is so basic to our subsistence and our spirituality. What I hope to do is not only write codes, but also help train grassroots people.

Benishi Albert: As indigenous people we have to organize differently. We fight the same struggles, but in fighting things like MRS facilities on our lands or landfills or incinerators, we can't get legislation passed like other communities to stop them because we are sovereign nations

As a young person I think that it is also important that I help other young people recognize that they are contributors, and to recognize the difference between real change and pacification. The youth movement among people of color is growing. We start from our own communities, and then work out and educate.

Isaiah Madison: What are some of the things you're doing in terms of organizing young people?

Benishi Albert: There is a youth task force within SOC which has 18 people from different organizations in the South. It's important we have our voices included in decision-making. We have limitations because we are in school and have few resources, but we can organize and be involved in strategies with everyone else.

We don't want to be separate, because it would be like fighting the same struggle separately. But we also want to be recognized and have our voices heard and let people know there are young people out there who are organizing.

Building a Movement

Isaiah Madison: Moving to another level, how do we organize in terms of building a movement across the South?

John McCown: Sometimes when you're actually involved in the struggle you get the feeling that you might be out there by yourself. What happens when we come together is we realize that we're not alone. When I saw Charlotte Keys stand up and talk about the poisons in her community and how people are dying, it gave me energy to go back home and say no, we can't have this in our community.

Mattie Mathis: We know that to disempower our enemies and to take control, we all need to participate and get together. We all have the same problem in that we're poor. Whether we're black or white or Indian, we don't have money — so we have to have people power.

Connie Tucker: We need to bring the forces of all these local struggles together into a regional effort that will evolve into a national effort for social change. We have to build local leadership, no question about it. But we also have to link the struggles so they are born into a movement that can seek out resources and fight to impact public policy.

Cynthia Smith: But we've got to make change at the local level first so we can empower people and elect some new politicians.

Connie Tucker: That's right. I think the first approach we ought to take is to do mass education - not only of our own people, but of our elected officials. We hope to provide a code of ethics for people to use in their communities, so they'll have a tool that speaks directly to the issue of environmental justice.

Anne Braden: I think we have to learn from history. The great struggles of the '60s impacted the whole country when people in the network focused on particular places. A lot of people went to Birmingham, Jacksonville, Selma from other places to support grassroots struggles there.

We need to develop the machinery where if something' s happening in Noxubee, Mississippi, other people will show up in Noxubee, and the country’s going to hear about Noxubee. When they hear about that, they' re going to know about Hancock County, too. We've got to build a regional struggle around specific local struggles.

Overcoming Obstacles

Isaiah Madison: What are the obstacles that prevent us from building the kind of national movement you' re talking about?

Connie Tucker: One of the obstacles is the commitment to not be disunified. What we are doing here is beginning to make a commitment to each other that we are going to work together.

Another obstacle is to be able to look beyond our local struggles. A lot of folks are dealing with environmental issues under white-led, single-issue organizations. They’re concerned about getting that incinerator out, even if it means putting it another community. They’re being overwhelmed by the pressure of the local struggle and not seeing the value of linking beyond the local community so that we can make a national impact.

Isaiah Madison: Any other obstacles, barriers, problems?

John McCown: Egos. Industry is going to exploit whatever barriers it can use to keep us apart. If we don’t come together and quit focusing on the fact that we all look different, all of our lives are in danger.

Pat Bryant: The number one problem is race. As long as there are communities of color where it is safe to poison people, send police to beat them up, and relegate them to substandard housing environmental poisons will continue. Race is at the heart of it.

Nick Aumen: I work with the Sierra Club, a predominantly white, middle-class, West Coast organization. One of my agendas is to focus more attention on the South. My personal goal is to look to the day when a corporation that’s seeking an incinerator or a landfill will put it in the richest, whitest community.

John McCown: Hancock County in Georgia is 80 percent African American. It suffers from one of the major obstacles communities of color are facing in the South—economic red lining. In 1986, the Atlanta Constitution found that industries owned by white America avoid any community with an African American make-up of over 30 percent.

That's why hazardous waste incinerators, prisons, and landfills seem so appealing. We haven't been given our share of the pie for years. Then all of a sudden companies come in and say, "You ought to be good and desperate now. How about this incinerator? How about this prison? How about this landfill?"

Cynthia Smith: The frustrating thing in Hancock County was that black elected officials refused to hear the facts about environmental racism. We educated them about the incinerator in 1987, and they went right back in 1988 for a 900-acre landfill because they wanted the jobs.

Virginia Sexton: Governments need revenues and the communities are poor, so they see it as a means to better them selves. Companies promise jobs and grease palms. That's their payoff - to talk all of us into what's already been decided.

Delois Gore: Black leaders have been bought off. This is a phenomenon we are observing all across the region. We are fighting two toxic waste facilities they are trying to put in Noxubee County, Mississippi, a 72 percent black county.

Cynthia Smith: An editorial in the paper said communities ought to quit squawking and take these facilities because all we have is uneducated, unskilled labor. For the writer to say that environmental racism isn't real was really an insult.

Pat Bryant: The same people we put into public office are representing big corporations who want to do us in. For the last eight years we have fought an uphill battle to get environmental organizations and our government - both controlled largely by white men - to recognize that environmental racism exists. Yet many environmentalists say we shouldn't try to organize the civil rights movement in the middle of the environmental movement.

Isaiah Madison: It's past midnight, so I want to bring the discussion to a close. What we've really heard this evening is a living statement that captures the history of a movement in the making. But all of this is prologue. Our challenge is to be true to ourselves, to speak to the questions that crush us as people, to refuse to be silent lest we be enslaved. By raising our voices, we can build a movement that has the power to raise up black and white, yellow and brown, tan, Jew and Gentile, Hispanic. One people, pulling together to forge a movement.

Tags

Isaiah Madison

Isaiah Madison is executive director of the Institute for Southern Studies. He became interested in community economic development when working as a lawyer in Mississippi. He handled cases for black farmers having difficulties holding onto their land and became involved with the Federation for Southern Cooperatives. (1994)