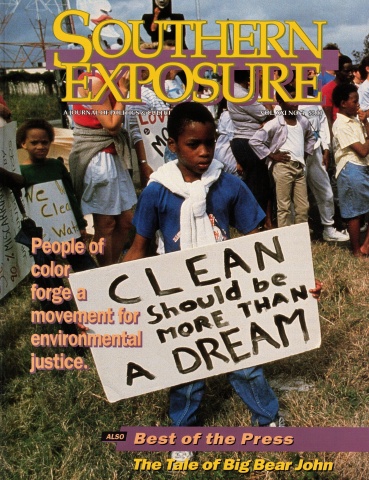

This article originally appeared in Southern Exposure Vol. 21 No. 4, "Clean Dreams." Find more from that issue here.

It begins with a man and a poor one-eared horse are standing on my porch. They look big as planets behind the caved-in mesh of the screen, their heads not a yard from my eyes.

"Mister," I say, "there's a loaded pistol aimed smack at your face and it's goin' off at the count of two." I'm holding a .357 magnum straight out.

He turns the animal around but takes the four steps down slowly. Deliberately. He is a handsome man, but crazy-looking too. They take their time getting out of the yard and into the trees.

It's almost dark. I latch the screen and turn on the porch light. The bolt on the inside door has been broken for a year. I whistle the hounds in from the back. They didn't hear the stranger. I know they were nosing around in the trash I threw out last night, digging at salt pork scraps and bloody meat wrappers. I could beat them.

Had to be crazy to come up on a house like that, I think. A horse on the porch. I go back to peeling potatoes. I throw skins to Rover John, who will eat them, and toss half of a peeled one to Jackson. "Spoiled, spoiled," I say to him. I dice up the potatoes and put them in a pot and fill it with cold water.

I wish some friend would come by, but it is mid-summer, and most of my neighbors have company from far off. Relatives. Daughters and sons and grandchildren who have married and moved away and only come back to hollers for three or four days in summer. They can't wait to get back to their cities and stores, their telephones and brought-on food. They think they have made some great escape, that all the things they hate about this place (for starters, the poverty that embarrasses them and the shadow of God in every corner), are far from them. Like God don’t just sneak up on you.

When the potatoes are done I pour milk into the pot. I mash them with a little fork and put in a little fresh dill and onion and butter and make a soup. Far off a little thunder mutters to itself, like it is searching for something. I am hoping the stranger and his horse are far off by now.

My great-great-grandma Early married a stranger. Found him at night raiding the vegetable patch while the moonlight and rain poured down on his yellow hair. He was sick to the bone. She saw by his clothes that he was a Rebel and thought he was a deserter. His name was Jeremiah. Early was 15 then. She hid the boy in a rock cave behind the house. Was supposed to be only for one night, but she liked him so well she just kept him, and the family though that was all right because he was so puny and almost crazy from war. After a while he liked her too.

I am thinking the man was right good-looking but if he comes back in the middle of the night I will have to blow his head off. I push the sofa in front of the door. The back door has a bolt. The windows are tight and locked and the panes are small. He is too big to fit through any of the windows. The front door is surely the least defended. I try to make Rover John and Jackson lie down in front of it, but they won’t. I carry the soup upstairs to my room.

Early was half Cherokee. She knew so many things and wild birds would eat out of her hands. Her mother looked sort oflike an elf, though she was fullblood Cherokee. Early's father was a Welshman but looked like some kind of little troll. Neither one of them looked like a human being at all, but Early, by the grace of God, or just plain luck, was all right.

I eat my soup and try to think of pleasant things. Tomorrow will be full moon and I will set out more onions and carrots, if something bad don't happen. I'll wait until the shrinking moon to plant the second batch of corn. I think about the think about the things I own. This house. Two horses. My Rover John and Jackson. My chickens and the Bantam, and the two turkeys.

I have got a hundred acres crowded with oak, ash, hazel, red maple, pine, black walnut, redbud, dogwood, laurel, magnolia, apple, cherry, and catalpa. The largest catalpa goes past the roof, its elephant ears covering half my bedroom window by July. Sometimes I sit in the fork of it drinking coffee or maybe taking a few sips of bourbon, or have a little bourbon in the coffee, or a little coffee in the bourbon. I do not ever fall out of the tree.

My land is deep, deep, deep into the hills, and the stream that runs through it is pure, free of the poisons leached from mining wastes. I can drink from the stream and cook with its water.

There is little to fear here, except for strangers sometimes, and of course the spring rains, gully washers that can tum into deluge, making the creek beds and the roads one thing. It rarely happens in summer. Anyway, my house is built on high ground. Of course, things can happen in storms - boughs of trees can come crashing through your roof and knock you in the head and kill you, or send glass shooting every which way to blind you. Maybe I am a worrier. Neighbors are far.

A shiver wriggles through me. There's a little bourbon left in the cupboard in the bedside table and I reach for it.

Early was 15 when she stole Jeremiah from the Army of Northern Virginia. I am 36 now. I've had boyfriends, long-term, before. One for three years, another for two. One for five. The love life with the first two was purely adequate, but the recollection of the last will keep me awake sometimes, or wake me in the early morning, or will come to me while I am feeding the hens. His name was William.

The first boyfriend plain and simply could not be bothered with self-improvement. He would not read a book nor tax himself with a new idea. I don't know why I kept him for so long. The second liked church too much, going twice on Sundays and getting to where he was sure enough too good for me.

William would have been the one then, only when he finally got up enough nerve to propose, I went and acted like some wild beast that could not be caught. Cold feet was all, but he left right after I said let me think about it. Just left me and it was a shock to my system.

The first thing I did after William was get rid of the fourposter. I learned then that I could make it through a winter without a man beside me, something like hibernation, only not quite so serious. I get a lot of reading done.

Come April, though, when the first shoots are pushing through the earth, I always know it, because that is when some force is making me re-arrange furniture that is fine the way it is, making me scold the hounds for nothing at all.

It has something to do with the smells. Smells from everything, alive and not. One breath of the spring air, of the laurel and redbuds, of the rhododendron and dogwood, even of the soft pin feathers of birds that line the nest and get mixed in with what the winds take up- and something sets up inside of me, inside anybody, I believe, quicker than aspirin, quicker than a drug. Say the one you love is beside you though, say rain or shine, then it is like a false spring always.

I am lucky in the earthly goods department. I have food and a little money and a roof overhead. I borrowed money once because I had a few debts backed up. I was young and had been a little of the spendthrift, which I am not now. It took me 10 years working various no-account jobs to pay that money back. I am still ashamed it took so long. Now I sell wild herbs to the state agriculture bureau which sells them to pharmaceutical companies. There is a good farmer's market over in Cumberland that buys my lettuces, squashes, beans, and black walnuts, and another over in the next holler. That's all the cash I need. The house was given to me a year ago by Gran when she went to live in the city and there is no debt on it. I grow all my own food. So.

The horse had one ear. I am thinking maybe the man shot it off. He could have been a lunatic. I feel a chill and decide not to take the empty soup bow 1 down to the kitchen. I set it on a table and tum out the light, pull off my shorts and T-shirt, get under the covers, and try to sleep.

Maybe he is one of those Vietnam vets gone mad. One did over in Harlan and shot a mother cat and all her kittens. I know the stranger saw my .357. I bought it at a pawn shop in Cumberland. I am a crack shot and he will rue the day if he dares to come back. Probably was a vet's pistol.

I think about Early again, how her blood runs in mine. I listen to the cicadas and wish a storm would come. The cicadas stop and I hear the thunder again. It's moving a little closer, like when I have had four or five cups of coffee.

It strikes me that maybe he is from the government. Maybe a plainclothes postal carrier. No. Horny Gaitskill is our equestrian carrier. They wouldn't send a fill-in who would ride up on our porch at night on a one-eared horse. Maybe the man was sick. Maybe now he is dead because of me. I can't sleep.

It is early the next morning. Birds are just up. Something tells me not to get the gun. I don't want to stand at the door watching him, like a fool, waiting, so I go out onto the porch and stare straight into his eyes. Even 30 yards away I can see their steel blue.

I read somewhere that if a great ape charges at you, you should stand your ground, don't budge an inch. He will come right up to your nose, but you just stare him down. The man keeps coming but he holds his hands up. “Don’t shoot,” he says, he keeps walking towards me and looking to where my arms are behind my back, where I might have a gun. He is very tall. He has long hair, and the sun is behind him, turning the pale strands to prisms.

Suddenly I am put in mind of the Bible scenes about angels, how they were all aglow, and how you may entertain one unawares. I feel like a fool for the thoughts I’m having.

“I bought the Caxton place, two miles yonder,” he says, motioning with his elbow. “I’m your neighbor.” I stare at him while he lowers his arms slowly. “Samuel Long,” he says, and makes like to shake hands with me, but I won’t until I put enough questions to him that I am satisfied he is neither an angel nor a murderer. Then I shake hands with him.

The way he asks for our first date is like this: “I don’t reckon you would care to go snaking?” And that is exactly what we do. We hunt rattlers from dawn to noon. Sam catches six and I get 14 and he’s not upset. He’s glad for me. We sit in a stand of young pines and have our picnic lunch and talk. Little things hop around on the basket and the food and over our sun-burnt skin, but we don’t mind. He says he bought the Caxton place with Army money. He doesn’t talk about the war though and I don’t ask him anything about it. He does look tired and too lean and I want to feed him, same as all the women in my family have wanted to feed men to comfort them, back as far as I can remember, no matter how tough a woman it was. That night I make him a dinner of ham and biscuits, corn bread, green beans, fried potatoes, poke salad, and coffee. He doesn’t talk when he is eating. Not for the whole meal. I like that. I’m used to eating by myself in a peace and quiet, so it’s nice to be with someone else who likes the taste of his food and isn't all the time talking.

In the storm cellar, I keep Gran's scrapbook. I keep it there so it's safe from the tornados and floods and robbers and so on. There is an old, old letter in it that's from Jeremiah to Early. After dinner I show it to Sam. It was written when Jeremiah went to be a lumber jack for awhile. He had to do that so as to be able to support their child that was on the way. He had to be gone from home for three months.

The letter says how when he was in the war he had no idea that he would ever love Early. Then God showed him the way to her garden and now they had this precious new life coming and he would love her and it forever. He signed the letter "Your husband and its daddy, Jeremiah Stone." Except for his name, the correctness of the spelling is not even close.

We play a game, Sam and me. I don't guess his game is the same as mine, but I know he is playing something. My imaginings change from time to time, and I expect his do too, but my main one, my favorite one, is that he is Jeremiah and I am Early.

Sometimes he comes riding slow through the dogwood, up and down, up and down, on Thompson, like in a dream. Thompson's torn ear makes my heart ache. I imagine the two of them scouting ahead, coming through the green trees, their hearts beating fast. They hear something. Sam pulls his saber as they come to the dogwoods. Sam holds his saber high and digs his heels into Thompson. The blade pierces through the dogwood and catches the sun, while white blossoms fly up and flutter down, covering Sam's head and shoulders, scattering over Thompson's flank. The two of them look like some knight and his steed - maybe King Arthur and a horse he loved well. I don't know. Then there is a terrible noise, the blast of a cannon, I think, and Sam is thrown off. Thompson falls and that's how he gets his ear tom off. But then it all clears and I see Sam and Thompson, whole and healthy, except for Thompson's ear, riding towards me, both of them are wearing silly grins.

Thompson is human to me, or more than that. He's human to Sam too, that's why both of them come up on my porch like that. Thompson wanted to, was the only explanation Sam ever gave me. He said he was coming over to make my acquaintance and Thompson just wanted to climb the steps. "He was in a hurry to meet you," Sam said.

In the fall, we go to the drag races. The season is so exciting, like it's on fire. The air is changing, the leaves are the deepest blazing reds and sunny golds, and they fall on everyone like things for us to play with. There is the smell of pork smoking everywhere, and of the last ears of com roasting on grills. People all over the holler are cooking weiners and apples and com cakes out of doors, and there is this feeling of deep, deep sunlight all around us, sinking into us, going into our bones, maybe to protect us from the coming chilly days.

Then there is the drag race. It isn't with cars, which I truly like better. They call it a drag race in jest. Darby Yates, he owns the little store, the only store in the holler, up the road from me, well he is the only one to "drag" the sack of corn fat to lay the scent. The com is in a cage three miles away, up in the middle branches of a hickory, Sam has got Jackson held back tight and I've got Rover John, but I'm not wagering on either one. I put my money on Darby's young hound. Sam put money on Jackson. It gets dark and the miner's carbide lights go on one by one and the hounds get more excited. Rover John and Jackson are whining like puppies, though they are seven and five. I'm embarrassed and wish Sam had wasted his money some other way.

With all the blackness and the lights flashing like stars in it and the noise and the men's voices getting louder, out-doing the women's, the whole thing begins to seem silly to me. I say that to Sam, that it's silly, and he just looks at me with no smile at all and says, "Don't you want to win?" He goes off with Jackson pulling him for a ways and then I can't see them. I let Rover John jerk me around and I think of swatting him one and making him go back home with me because suddenly I can't stand this stupid men's game, but then he goes crazy, he's really onto the scent, and I go with him as far as I can, then I let loose of him and watch him stray far left of me, sniffing the ground and turning in a circle like when he has to go, but then he shoots straight ahead and I chase him with my light. He's gone in a few seconds, but I can hear his bark, and I keep running. I run for maybe 20 minutes, and then I have to walk. My mind is somewhere up ahead with him though, pushing him on. Go on, you want to win, don't you? I follow the thick of the noise. Half hour later, there's the tree. There's Darby and most of the holler, and at least a dozen crazy hounds, lathered up and barking their heads off so hard I'm afraid their throats will bleed. Sam's got Rover John by his collar, patting his head, saying something.

Most of the lights are focused on the poor little coon eight or 10 feet up the tree. His eyes are like burning coals. They all start to tell me Rover was the first to the tree. Sam and I could be soaring 20 feet above the trees.

Some of us go by Darby's store for sodas. We sit outside on tree stumps and on the weeds. We can see the flickering lights of cities spread out in the valley below. Lightning pulsates high above them. The lightning is in the clouds that are on a line even with us. Sam says by the time we get home it will come a full blown electrical storm. Some of the folks ask me what I feed Rover John and Sam tells them coons. Everybody laughs and Sam rubs his nose with his fists and grins. I think of making love in the storm.

We have a dance just for our holler. Horny Gaitskill and Darby Yates and some others prod around trying to get Sam to tell about the war, but he will not. All night one or another of the Mten comes up and pats Sam on his shoulders and mumbles something like, "There's a good man," or such.

Except when they sneak into his dreams, he handles the memories all right. Sometimes he dreams of bodies falling through jungle trees, first they' re little white balloons, soft and thin walled, not a lot of air in them, and they float down quietly, then, when they' re almost to his face, they tum into people, roaring and screaming like wild animals.

When he first got off the bus at Richmond, he tells me, right after he was discharged, he walked out of the station into the sunlight and smack into a bunch of people holding blownup pictures of the My Lai massacre. He wasn't at My Lai, but he felt like he was. Sam kept his eyes on the blue sky and his mind on McDonald's, a kind of self-defense. There was nothing to say to anyone, nothing that would help, he says, and probably never will be. He only wanted some peace and quiet and some plainness: water and grass and sky and a good horse. Then he looks at me and adds, like an afterthought, how he needed a good old plain woman too, and I am obliged to wrestle him off the porch, where he is telling me this, and into the clover, cool and deep and green.

Sometimes at night, after he thinks I am asleep, Sam slips into the storm cellar and brings up my scrapbook. He turns the pages slowly and looks at the pictures of Civil War tombstones. There is a photo too of Early’s and Jeremiah’s tombs, side by side. There’s a confederate flag and a photo of Jeremiah’s uniform. Then Sam turns to the letter and reads it slowly. Sometimes he smiles. Sometimes he just quietly closes the album. I’ve seen him do all that maybe three or four different nights. I don’t ever bother his thoughts. I slip back into bed after a while and wonder what it is we’re doing. We don’t have any plans. We will talk to Thompson and ask him questions which the other one will answer for Thompson, and the days and nights go by and we’re just happy as frogs.

Some people can’t stand it. They try to tell me I could be sitting on a powder keg. “You hear how more of them from the war are going crazy now?” they ask. Or, “You recollect that mama cat and all her babies?” But I don’t listen.

Sunday we go to Cumberland to visit Gran. Her mind is slick as glass and twice as sharp. She lives in a rooming house with six other “oldies,” she calls them, mostly women. She’s 82. “Don’t you marry her less’n you love her,” she says to Sam the first time they meet. “Don’t you never marry no one, ‘cept for pure ole love,” and she crosses her hands over her chest and looks up to the ceiling, hugging herself tight, then she laughs.

“I won’t,” Sam promises. “Why I don’t even like her,” he says and I hit him. “I believe you children already are in love,” Gran says. “Oh, I know it,” I say, and Sam casts his eyes up into their sockets and makes a terrible writhing face.

“I want to show you off, you pretty thing,” she says to him, and leads him off to meet her friends. I stay in her room and browse through her books. She has books galore. There’s one, Diseases of Mystics, that strikes me, and I take it down from the shelf.

There is some mildew on the pages. It’s a very small book, I guess because the diseases of mystics are not all that many. Most of them are nervous afflictions, brought on, the author says, by a fretful nature—“Too much moon, not enough sun," he calls it. A zealot is blind to the kingdom of heaven, he says. As a way to quit worrying and avoid so much sickness, he recommends that people stop believing in time.

I'm thumbing through the book and wondering how a person could possibly not believe in time, when Gran and Sam come back. "Don't ask to borry that," Gran says to me, "you won't be needing it."

She likes to tell us the old family stories from the Civil War, and we like to hear them. One Sunday she tells us the story about how Jeremiah walked away from his unit right before the Battle of Chickamauga. He was drinking water from a little bend in a stream, about 30 yards from his company. He looked up and standing in front of him was a man all made of blue light, shimmery like the birth sac of a new foal. Jeremiah stared, water still dripping off his chin, and the man just stood there. He was across the stream, maybe two yards away. Jeremiah watched the man back up slowly. Then he stood without wiping his face, while the man sort of beckoned to him. Jeremiah waded to the other side, stepped up onto the low bank, and followed him for miles. The man finally disappeared into thin air about 30 yards from Early's garden.

"I can't believe that Gran," I say in the middle of the story. "Well, don't then," she says.

I listen politely for a while and then ask, "Did Jeremiah have a one-eared horse by any chance? And did he carry a saber?" I half glance at Sam, expecting him to snigger at me, or at least to be grinning, but he's looking to Gran instead, quietly waiting for her answer.

Then Gran says, "No. He was infantry come up with Longstreet. They was gonna help Bragg's Confederates in Tennessee. He warn' t with the cavalry, dear heart, now shut up and let me tell it."

It is nearly winter now. We've got maybe two weeks before it's too cold to sleep in the treehouse we built last spring. We sleep in two zipped-togethe~ bags and are warm as moles. At night Thompson stays in the barn, his long chestnut back covered with three wool blankets.

We go to sleep in a cradle of branches under a quiet moon, buried in dreams or in nightmares, and wake up to the shout of the red sun rising, turning itself inside out for us, burning itself up for every living thing, every single day, like it's some kind of crazy fool. Like there is no tomorrow.

Tags

Sharon Claybough

Sharon Claybough lives and writes in Lizella, Georgia. (1993)